Clint Johnson's Blog

April 7, 2019

The sinking of two destroyers named USS Jacob Jones and how the USS Roper avenged one

This is the tale of two unlucky destroyers named for an unlucky commodore, and the destroyer that avenged one of them.

Perhaps the name, Jacob Jones, was cursed. Jacob Jones was born in Delaware, but was an orphan by the age of four. He eventually became a doctor, found love and married but his wife died not long afterwards. Once again, he was alone and grief stricken. Abandoning his medical practice, he joined the U.S. Navy as a midshipman at the old age of 31 when it was common for boys as young as 10 to come on-board as a midshipman.

Jones’ luck turned even worse. He and the rest of the crew of the USS Philadelphia were captured by Barbary pirates in 1803 and not freed until 1805. He was captured again at sea by the British during the War of 1812. Released, he lived a productive life in the U.S. Navy until his death in 1850.

But, starting 67 years after the commodore’s death, Jones’ bad luck returned. Two of the three ships named for him would be sunk.

The first USS Jacob Jones (DD-61), a Tucker class, was not one of the original American destroyers in the squadron sent to Queenstown, Ireland, in May 1917 to begin our nation’s participation in World War I. She was left behind to act as a mail ship, but the bad luck associated with the Jones name continued. At some point during a short stay in Philadelphia, someone, probably a crewman, opened her sea cocks in an effort to sink her at the dock. The sabotage was discovered only after two feet of water had filled her hull.

The first USS Jacob Jones (DD-61), a Tucker class, was not one of the original American destroyers in the squadron sent to Queenstown, Ireland, in May 1917 to begin our nation’s participation in World War I. She was left behind to act as a mail ship, but the bad luck associated with the Jones name continued. At some point during a short stay in Philadelphia, someone, probably a crewman, opened her sea cocks in an effort to sink her at the dock. The sabotage was discovered only after two feet of water had filled her hull.

The Jacob Jones eventually did make it to France as part of a squadron escorting convoys. She was sunk on December 6, 1917, by a German U-boat off the southern coast of England. Hit by a single torpedo from the U-53, one of Germany’s most successful submarines, some of DD-61’s crew was killed by the initial explosion. More were killed when sinking depth charges exploded underneath the survivors floating in the water. She was the only American warship lost to enemy action in World War I.

The second USS Jacob Jones (DD-130), a Clemson class, was given the Jacob Jones ship name while still being constructed in February 1918 in honor of the destroyer that had been lost just three months earlier. USS Jacob Jones (DD-130) sailed widely during the 1920s and 1930s and seemed to have shaken off the bad luck.

The second USS Jacob Jones (DD-130), a Clemson class, was given the Jacob Jones ship name while still being constructed in February 1918 in honor of the destroyer that had been lost just three months earlier. USS Jacob Jones (DD-130) sailed widely during the 1920s and 1930s and seemed to have shaken off the bad luck.

On Feb. 22, 1942, the Jacob Jones thought it had encountered a U-boat just outside New York City’s harbor. She dropped 57 depth charges on a contact, resulting in an oil slick rising to the surface, but no wreckage. Despite the captain’s protests to his superiors that the target was moving, the Jacob Jones was not credited with finding a U-boat.

On Feb. 28, 1942, while cruising off Cape May, N.J., she was hit by two torpedoes, fired by the U-578. Only 13 crewmen survived and one of them died after rescue.

The similarities in the sinkings of the two Jacob Jones are striking. DD-61 was the only American warship lost to enemy action in WW I. DD-130 was the only American warship lost to enemy action in American continental waters in WW II. Both were sunk by U-boats at night. Both lost crewmen to their own depth charges exploding and killing survivors floating in the ocean. Both lost most of their crews.

USS Roper

On April 14, the USS Roper (DD-147), a Wickes class, would get its revenge for the loss of the Jacob Jones. The Roper was already famous in the United States for having rescued a lifeboat with a newborn baby on-board. The mother had been so grateful to the crew that she named the baby Roper. The birth and rescue of the baby made national news.

The Roper was cruising off Nags Head, N.C. on April 14, 1942, when it made a surface radar contact that the captain thought could be a patrolling Coast Guard ship. He ventured closer and was rewarded with a torpedo passing his destroyer’s length. The Roper turned on its search light and spotted the U-85 running on the surface. One of the Roper’s 4-inch deck guns hit the conning towner before the submarine could submerge. Most of the sub’s crew abandoned their submarine before it sank beneath the waves.

The Roper’s captain was not positive that the submerged submarine was damaged enough to have sunk. He thought the captain had submerged to avoid more gunfire. The Roper continued to drop depth charges, which killed all of the U-boat crewmen in the water. Later questioned if he could have rescued the crewmen, the Roper’s captain explained he thought another U-boat could be in the area. To pick up the Germans would have meant stopping his destroyer, giving any lurking submarines an easy target.

The U.S. Navy tried to examine the U-85, sunk in less than 100 feet of water, but no effort was made to go inside it. Had divers using rebreathers or air hoses gone inside, they might have recovered an Enigma coding machine. That was finally brought to the surface by sport divers in the 1990s.

To this day, some stories still circulate that the U-85 was trying to drop off spies, but those stories seem unlikely. All of the crew could be accounted for as crewmen from papers recovered from their bodies. No one extra was on-board. Even if spies had been aboard, the action was 18 miles at sea, hardly where she would be in preparation to dropping off spies in rubber boats. And, if they had been dropped off, the spies would have had to cross another sound to reach the North Carolina mainland. And if they had reached the mainland, there was nothing there to sabotage; no defense plants, no cities, not much of anything other than pine forests.

It was an early victory for the U.S. Navy against the U-boats that would roam the American Atlantic coast for the next year. The second USS Jacob Jones (DD-130), sunk just six weeks earlier, had been avenged.

One other ship would pick up the name USS Jacob Jones (DE-130), commissioned April 29, 1943, just over a year after the Roper had sunk U-85. The Navy even assigned the third USS Jacob Jones the same number as the second USS Jacob Jones. The destroyer escort would lead an uneventful service during the rest of the war, never encountering the enemy. She would be sold for scrap in 1973.

Whoever assigns ship names in the U.S. Navy has not tested fate again. So far in the 21st century, the USS Jacob Jones name has not been assigned to another destroyer. (All U.S. naval destroyers are named after naval personnel who have established themselves as heroes.)

The post appeared first on Clint Johnson.

April 4, 2019

The Japanese Targeted The Wrong Ships at Pearl Harbor

USS Monaghan (DD-354) would be undamaged at Pearl. She would win 12 battle stars during the rest of the war. but would sink in Halsey’s Typhoon in 1944.

The Japanese attack on our Pacific Fleet on Dec. 7, 1941, seemed devastating. Of the eight battleships we had in Pearl Harbor that day, all of them were sunk or heavily damaged. Three cruisers were severely damaged. Three destroyers were put out of commission. Nearly 200 aircraft were destroyed. More than 2,400 Americans lost their lives.

The Americans did get lucky. All three of the American aircraft carriers normally at Pearl were at sea far from the attack. Also, the Japanese cancelled a planned third air attack meant to target the fuel tanks, dry docks, and ship repair facilities as they feared adding another attack would force their tired pilots to land after nightfall.

What President Roosevelt called “a date that will live in infamy” was really not at all devastating.

Of the eight battleships hit that Sunday morning, six would be repaired and would put back to sea. All three cruisers would put to sea. Two of the destroyers were total losses, but the USS Shaw (DD-373), its bow blown off in a spectacular explosion, would return to sea within six months.

The Japanese placed a great value on the American battleships they sank, but they targeted the wrong ships.

All of the American battleships were relics dating back before the U.S. even entered World War I. The six battleship that were refloated would accumulate 41 battle stars during the rest of the war, meaning they engaged the Japanese 41 times. However, that would include only two battleship-to-battleship battles at Guadalcanal in late 1942 and Leyte Gulf in late 1944. Most of those battle stars would be won by shelling beaches where the battleships were far out of reach of Japanese shore batteries returning fire. No American battleship was sunk during the war after the attack on Pearl.

The eight heavy and light cruisers at Pearl would do better, accumulating 81 battle stars. Only the USS Helena (CL-50) would be lost in combat.

The ships the Japanese should have feared – and sunk – were the 30 destroyers that were in port that morning. The 28 destroyers that continued fighting accumulated 257 battle stars during the rest of the war. Fifteen other destroyers were away from port that morning. They would accumulate 105 battle stars. There were six former Clemson class World War I-era destroyers in port that had been converted to minesweepers and seaplane tenders. They would accumulate another 23 battle stars. There were nine even-older Wickes and Clemson class destroyers converted to minelayers that would win 53 battle stars.

The 55 destroyers that called Pearl Harbor home on December 7, 1941, would win 438 battle stars through August 1945. That’s more than 10 times the number of battle stars accumulated by the principal Japanese target – the battleships.

The post The Japanese Targeted The Wrong Ships at Pearl Harbor appeared first on Clint Johnson.

March 31, 2019

Why did the U.S. not react to attacks on three American destroyers by U-boats in Oct. 1941?

We all know the U.S. entered World War II on December 7, 1941 when the Japanese attacked our Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Why didn’t we go to war when Germany attacked three of our destroyers weeks and months before Pearl Harbor?

On September 4, 1941, the USS Greer (DD-145), (near left) a WW-I era Wickes class, was about 175 miles from Iceland with a load of mail and supplies, when she got a warning from some British ships that U-boats were in the area. The Greer soon made sonar contact, but did not make a run at the submarine. Just before 1:00 p.m. lookouts spotted a torpedo, then a second one. The Greer responded by dropping eight depth charges, then 11 more over three hours. No debris ever surfaced.

Three days later, President Roosevelt made a radio address where he warned: “From now on, if German or Italian vessels enter the waters [meaning American defensive waters], the protection of which is necessary for American defense, they do so at their own peril.”

But, he did not ask Congress for a declaration of war.

On October 17, 1941, the USS Kearney (DD-432), (far left) a one-year-old Benson class, was part of an escort for SC48, a 53-ship convoy heading to Great Britain, when she was forced to go dead in the water when a British corvette cut across her bow. The U-568 took the opportunity to fire a spread of three torpedoes. One hit on the Kearny’s starboard side, killing 11 American seamen. The Kearney was able to make port.

The President responded with another speech in which he said: “America has been attacked.” Later in the speech he said: “The forward march of Hitler and Hitlerism can be stopped – and it will be stopped. “ Later he said the U.S. Navy had been given orders to “shoot on sight.”

But, FDR did not ask Congress for a declaration of war.

On October 30, 1941, the USS Reuben James (DD-245), a tired Clemson class that had been at sea for 20 years, took a torpedo in the port side from the U-552. While the Kearny’s new 5/8th inch thick tempered steel stood up to its torpedo, the 20-year-old 3/8th inch thick rolled steel of the Reuben James did not. The forward magazine exploded, breaking the ship in half. More than 100 men were killed , including all of the officers.

Still, the President did not ask Congress for a declaration of war.

More than 110 Americans had been killed in three separate U-boat attacks on American destroyers in two months, but President Roosevelt did not directly retaliate against Germany.

Historical opinion is that FDR did not push for war against Germany for the loss of the two destroyers because he did not yet have the bulk of the American public behind him. In late 1941, many Americans were not even sure they liked the idea that the U.S. was providing convoy escorts for the merchantmen heading to Great Britain.

Curiously, while the U.S. government was not particularly angry about the loss of 110 American seamen to two German U-boats, a pacifist singer was. Woody Guthrie recorded The Sinking of the Reuben James asking: “Did you have a friend on that Good Reuben James?”

The post Why did the U.S. not react to attacks on three American destroyers by U-boats in Oct. 1941? appeared first on Clint Johnson.

February 28, 2019

How a 32-year-old “Old Man” inspired his shipmates on the USS Gwin

Within a few minutes after I finished a radio interview on a Colorado station, I got a note on my website from a Charles Frazier. Mr. Frazier, a Navy veteran himself, wanted to tell me the story of a great uncle he never met, Delbert Benton Connor.

Within a few minutes after I finished a radio interview on a Colorado station, I got a note on my website from a Charles Frazier. Mr. Frazier, a Navy veteran himself, wanted to tell me the story of a great uncle he never met, Delbert Benton Connor.

Delbert was one of three sons of the Connor family from Kemp , Texas. Growing up on a farm, Delbert, or “Deb” as he was known, did alright for himself for a while, running a hunting and fishing camp for wealthy Dallas lawyers. According to Deb’s parents (Mr. Frazier’s grandparents), he was a likable young man who the lawyers appreciated. They talked about backing him if he wanted to go back to school and get an education that would allow him to go to law school.

But, once the Depression hit, even the lawyers were without much money. Ded did not get that dream of going back to school. But he was a hard worker. He found a job and saved his money, even buying the family’s first radio and later a truck when his parents had been using mules and wagons for transportation.

When the war came, Deb joined the Navy, even though he was in his late 20’s, nearly a decade older than most young recruits. Though he was not an experienced seaman himself, the other, younger crewmen looked up him. Deb told them stories of his family’s cotton farm, of his beautiful sisters, and of his brothers. One of his brothers made a living riding bulls in rodeos. That brother joined the Navy and became a flight instructor. He likely was the inspiration for Deb to join the Navy.

Deb was assigned to the USS Gwin (DD-433), a Gleaves class destroyer. Sixty-six were built, one of the classes that preceded the introduction of the Fletcher class.

The Gwin escorted the aircraft USS Hornet  (that’s the Gwin getting close to the Hornet) on its mission to deliver General Jimmy Doolittle’s B-25 bombers close to Japan. During the Battle of Midway, the Gwin rescued many of the men when the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown was hit by torpedoes. Her first engagement with the Japanese came during the Battle of Guadalcanal on Nov. 14, 1942, when she boldly attacked a Japanese cruiser. She took two cruiser hits near the stern and retreated.

(that’s the Gwin getting close to the Hornet) on its mission to deliver General Jimmy Doolittle’s B-25 bombers close to Japan. During the Battle of Midway, the Gwin rescued many of the men when the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown was hit by torpedoes. Her first engagement with the Japanese came during the Battle of Guadalcanal on Nov. 14, 1942, when she boldly attacked a Japanese cruiser. She took two cruiser hits near the stern and retreated.

The Gwin made her way back to Mare Island in Vallejo, California, for more permanent repairs. Deb took leave to visit his parents. At some point over the Christmas holiday, he signed over his Navy insurance policy to them. When his father took Deb back to the train, he cried, somehow knowing that he would not see his son again.

On the night of July 13, 1943, the Gwin was part of the American force during the Battle of Kolombangara. While the Japanese had not yet installed their own radar, they had developed a device that detected American radar. Without the Americans seeing them on radar, the Japanese launched 31 Type 93 torpedoes (after the war they were nicknamed Long Lances). One of those Type 93s hit the Gwin amidships. The Gwin herself stayed afloat, but was sunk by an American destroyer so she would not be a shipping hazard, or recovered by the Japanese.

Of her 16 officers and 260 crew, just two officers and 59 crewmen were lost. But one was Deb.

After the war, one seaman who survived the war came to Texas to find Deb’s parents. The sailor explained that the torpedo had blown him into the air, but left him without a scratch. He sought out Deb’s parents to tell him that Deb was an inspiration to the younger men on the Gwin. He was handsome, strong and capable, just the type of man they wanted to grow up to be if they survived the war.

Delbert Benton Conner was 32 years old when he was killed. He was an old man compared to the other sailors on the Gwin,  but he was their hero.

but he was their hero.

I want to thank Charles Frazier, a hook runner on the carrier USS Kitty Hawk during the Vietnam War, for sharing the stories of the great uncle he never met. It is men willing to go to war who preserve the peace for the rest of us.

The post How a 32-year-old “Old Man” inspired his shipmates on the USS Gwin appeared first on Clint Johnson.

February 25, 2019

Dec. 7, 1941 – The Date An American Destroyer Attacked The Japanese at Pearl Harbor

For nearly 80 years we’ve heard: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date that will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

Welllllll…….that’s not quite true.

More than an hour and a half before the first wave of Japanese bomber and torpedo planes appeared above Pearl Harbor, the USS Ward (DD-139), a Wickes class destroyer commissioned in 1918, suddenly and deliberately attacked a Japanese midget submarine outside of Pearl Harbor. With its second shot from one of its midships deck guns, the Ward sank the two-man submarine, killing its crew. In other words, an American destroyer kicked off the United States’ involvement in World War II BEFORE the Japanese aircraft arrived. We attacked them before they attacked us.

The radioed report of the Ward’s sighting and sinking of the Japanese submarine was not acted upon by all of the superior officers who saw the written transcript. The report went all the way to Admiral Husband Kimmel who read the report and decided he would await further developments.

Kimmel was lulled into thinking the Ward had probably seen nothing since none of the other reports of submarine activity over the previous days had proven true. The Ward’s captain, Lt. William Outerbridge, also inadvertently softened his own warning when he proceeded to investigate a nearby sampan after sinking the submarine. The naval officers on Pearl reasoned that if Outerbridge was concerned about submarines, he would not have left his station to investigate a small fishing boat.

The Ward’s sinking of the Japanese submarine would not have changed anything about the Japanese air attack. By this time the Japanese Kates (torpedo bombers) and Zeroes (fighters) were already launching. But, what could have –and should have – happened if the Ward’s report had been believed is that the American fleet would have been on alert when the first wave of aircraft flew over Pearl Harbor.

Because they were not on alert, the crews of the ships in the harbor were so unprepared for an air attack that many of them had to break out ammunition cans and belt machine bullets before they could even shoot at the incoming Japanese aircraft. Some sailors resorted to firing at the attacking planes using rifles and Browning Automatic Rifles.

IF Outerbridge’s report had been believed, the Americans would have had at least an hour to prepare – for something. Not long after Outerbridge’s report reached Kimmel, radar contact was made with a large group of aircraft approaching Pearl. The privates operating the radar station were not taken seriously either when they reported a large flight of unidentified aircraft to their superiors. Radar was still new and many officers did not understand how it worked, and the early warnings it provided.

If Outerbridge’s report had been believed and the radar contact had been believed, the Pacific Fleet would have had time to prepare its anti-aircraft guns on board its ships. Only 29 of the 363 Japanese aircraft were shot down on December 7 during two waves of attack. It seems likely that the Japanese would have paid a much higher price if all of the ships’ crews had been called to general quarters in anticipation of an attack.

The Ward would be converted to Fast Attack Transport (changing its designation from DD-139 to APD-16. She would be attacked in 1944 by a kamikaze off Leyte. The Ward was so damaged that U.S. Navy superiors ordered her sunk by American gunfire so she would not become an obstacle to other American ships. The ship ordered to sink the Ward was the USS O’Brien (DD-725), a new Allen M. Sumner class. The O’Brien’s captain was Commander William Outerbridge, the same man who commanded the Ward on The Date That Will Live In Infamy. The day the Ward was sunk by Outerbridge was December 7, 1944, three years to the day that the Ward opened World War II.

USS Ward (DD-139)’s #3 gun crew sank a midget submarine 1.5 hours before the Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor

The post Dec. 7, 1941 – The Date An American Destroyer Attacked The Japanese at Pearl Harbor appeared first on Clint Johnson.

January 10, 2019

Did HMS Bulldog shorten World War II – BEFORE the U.S. entered the war?

May 9, 1941, may have been the turning point of World War II – a full seven months before the United States entered the war. If so, the free world can thank the crews of three British warships; a brand new, but tiny corvette, a 21-year-old former American Clemson class destroyer, and a smallish 11-year-old B-class destroyer

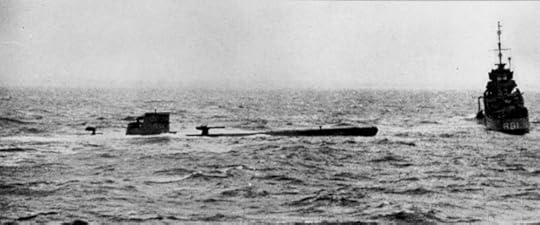

These three ships were part of the 10-ship escorts for Convoy OB 318 in the North Atlantic east of Iceland when they were attacked by several U-boats. The corvette HMS Aubrietia, just 205 feet long and displaying just 940 tons, found a sound contact and dropped a spread of depth charges. To the surprise of the B-class destroyer HMS Bulldog and the Town class HMS Broadway the U-110 popped to the surface. The crews of the Bulldog and the Broadway (the former USS Hunt-DD-194) began peppering the submarine with small arms fire. Even more surprising, the German crewmen began boiling out of the submarine.

The captain of the Bulldog saw an opportunity to capture the submarine. He put together a six-man boarding team as the rescued German crewmen were rushed below decks on the Aubrietia so they could not see what was happening.

Lt. Commander David Balme carefully climbed down the U-boat’s open hatch, fully expecting to be shot by a crewman who had stayed behind to set explosive charges. Another crewman, a telegrapher, searched the submarine’s radio position and found: “a coding machine…plugged in as though it had been in use when abandoned. It resembled a typewriter; hence the telegraphist pressed the keys, and reported to me that the results were peculiar. The machine was secured by four ordinary screws, soon unscrewed and sent up the hatch to the motor boat alongside.” Two hours later, while eating a sandwich while sitting at the captain’s desk, Balme found the July codes for the machine.

What Blame’s boarding crew had found was an intact Germany Navy Enigma machine used to encode messages, the first operational one captured during the war. Eventually the machine would be packed off to the top secret Bletchley Park where Alan Turing and a team of code breakers used it to help them break and stay abreast of the German naval codes.

Once the code was broken, the British were able to track the locations of German submarines and judiciously order course changes to Allied convoys to avoid some attacks.

The original plan of the Bulldog’s captain was to tow the captured U-110 to Iceland to examine the technology of the Type IX-B, a 9-boat sub-class of a very successful design. Fortuitously, the sub sank while under tow, but without any loss of any British seamen. Had the sub reached Iceland, it seems certain that German spies would have seen it and passed word back to Germany that the sub’s Enigma machine was likely captured.

Instead of examining the submarine, the British got to examine its first Enigma machine. The Germans never realized that their complicated codes were broken. Just how many Allied ships survived because of the capture is unknown. It is known that it was a top British secret. Prime Minister Winston Churchill did not tell President Franklin Roosevelt about the Bulldog’s capture of the Enigma machine until nine months later.

All three of these British warships survived the war. Not a single crewman spoke a word about the capture of the U-110 and its Enigma machine during the war and even decades later out of respect for their duty to remain silent about an important mission.

The post Did HMS Bulldog shorten World War II – BEFORE the U.S. entered the war? appeared first on Clint Johnson.