David E. Grogan's Blog

November 19, 2025

Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired) – 2 Iraqi Freedom Combat Deployments in a 20-Year Career

Military life is full of transitions. It begins with the transition from civilian to servicemember. Every two or three years thereafter, servicemembers and their families are uprooted from their homes, their jobs, and their schools to take new assignments, often far away in other countries. Sometimes military members must leave their peacetime assignments to deploy in times of war. Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired), knows these transitions all too well. Two Iraqi Freedom combat deployments and two unaccompanied tours in South Korea tested Freddy’s ability to deal with transitions. With the help of others at every fork in the road, he navigated the course changes successfully.

Freddy was born in Orange County, California, in March 1977. He was a third-generation American, with his great-grandparents having emigrated from Mexico years before. Freddy’s father could not read or write, but he could work hard and work hard he did as a construction worker in the booming southern California economy. His mother worked hard, too, helping with programs distributing food stamps. Their motivation was clear—get the family out of poverty and into the middle class.

When Freddy was three, his parents moved their family to Norco, a city in Riverside County just west of Los Angeles. His home was typical of Mexican American households in the neighborhood at the time in that it was filled with cousins, other family members, and neighbors needing a place to stay. Freddy grew to love them all as family.

Unfortunately, gang activity was rampant in Freddy’s community, and his family was not immune. Some of his cousins were deep into gangs and many did serious time in prison. Freddy never joined a gang but always found himself on the fringe heading down the wrong path. This played out in his schooling when he was expelled from Norco High School during his freshman year. He had no intention of completing school anyway because one of his older brothers had dropped out and he saw how his father was able to earn a living by working hard. He knew, though, that he had to at least go through the motions until he was old enough to drop out for good.

Unable to return to Norco High, Freddy started attending the Corona-Norco Career Academy—an experimental high school designed to give kids who had gotten into trouble a second chance at their education. There Freddy excelled because he had the freedom to work more independently than in the structured environment of Norco High School. He still skipped school frequently and ran with the wrong crowd, but because he excelled at his schoolwork, no one tried to rein him in.

Freddy Rocha (right) with his lifelong friend, Johnny Canales (left)

Freddy Rocha (right) with his lifelong friend, Johnny Canales (left)Although Freddy never joined a gang, he and his best friend continued to get into trouble. Then Freddy started talking to a Vietnam veteran in his neighborhood, Steve Blunt. Blunt served in the special forces in Vietnam and was the first person to talk to Freddy like an adult. He leveled with Freddy and told him, “You’re f’ing up fast and picking up speed.” But what really impacted Freddy was when Blunt told him that if he continued down his current path, his actions would devastate his mother. Blunt then suggested Freddy consider the Army as a way to straighten out his life.

Blunt’s message resonated with Freddy. Motivated to change his life, he convinced a buddy to visit a recruiter with him in the fall of 1994. However, because Freddy was still seventeen, he needed both his parents to give their written permission to allow him to enlist. He told them he wanted to make a new life for himself, and the Army offered him the chance to do it. He also wanted to marry his high school sweetheart and that meant having a steady job that could transition into a career. By the time he finished speaking, he had convinced his parents, and they gave him their permission to enlist. Their only condition was he graduate from high school first.

Freddy did just that in the spring of 1995, graduating at the top of his class. He spent the summer enjoying a few more months of civilian life in southern California, painting houses and working at fast food restaurants to fund his fun. In the meantime, the buddy he had gone to the recruiter with was discharged from the Army for medical reasons. He told Freddy to get out of his commitment, saying Freddy would hate the Army because he didn’t like being told what to do. Freddy ignored his friend’s advice. He had given the Army his word he would enlist, and he intended to keep his promise.

True to his word, Freddy reported as directed to the Los Angeles Military Entrance Processing Station on August 23, 1994. There, he passed his final physical and took the oath of enlistment. Now officially in the Army, he boarded a plane the next day on his way to basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Although Freddy’s plane landed in Atlanta late in the afternoon, the Army bus collecting new recruits for transport did not arrive at Fort Benning until 1:00 a.m. That’s when Freddy’s introduction to the Army and the South began. Everyone was directed to get off the bus and then escorted to the chow hall. There Freddy received a heaping helping of grits, which he had never tried before. He had eaten Cream of Wheat and Malt-O-Meal growing up, so he figured grits must be similar. Accordingly, he began to add butter and sugar to the grits. Out of nowhere, a recruit from West Virginia looked at him in disbelief and said with a strong southern accent, “What are you doing? You don’t put sugar on grits!” The experience made Freddy feel more Mexican than had ever felt in his life.

After a few hours of sleep, Freddy and the rest of the new recruits reported to the 30th Adjutant General Reception Battalion for in-processing. There they signed paperwork, received their uniforms, and got any shots they needed. They also learned their new training company assignments—Freddy’s was Delta Company of the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment.

Freddy’s transition to Army life was rough. To begin with, he approached basic training with a chip on his shoulder. He hated being told what to do and initially did not get along with the other recruits. He saw them more as rivals rather than fellow trainees. Whenever there was a fight or even the hint of a fight among the recruits in his company, Freddy was involved. On the third night, he finally got “whooped” in a fight. The experience made him more tolerant of his peers.

The drill instructors were another matter—they scared Freddy. They were “big dudes” who got right in his face and screamed at him. On the streets back home, he never would have let anyone do that to him. Now it happened routinely. However, after Freddy started to make friends, things changed. He began to enjoy the training, even when he had to do extra pushups for laughing at other recruits when they did something wrong. Just as with high school at the Corona-Norco Career Academy, he excelled.

Freddy graduated from basic training on December 8, 1995. Next, he was scheduled to go to Airborne Jump School, where he would learn how to parachute out of airplanes. When he had enlisted, he’d committed to the airborne infantry, but he really didn’t know what it was at the time. Now that he did, he had a problem with it because he was afraid of heights. As all the new soldiers lined up for their respective follow-on training, Freddy stood with the infantry soldiers rather than with those heading to Jump School.

When a sergeant told Freddy to get in the Jump School line, Freddy told him he was afraid of heights. The sergeant didn’t want to hear it. So, after heading home on leave to Southern California to marry his high school sweetheart, Freddy returned to Fort Benning and began Jump School. Although at times his legs shook with intense fear, he successfully completed all his parachute jumps and graduated from the school. With Jump Wings now adorning his uniform, he received orders to report to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. From then on, it was “Airborne all the way.”

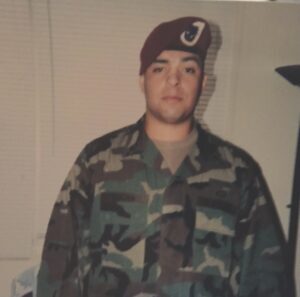

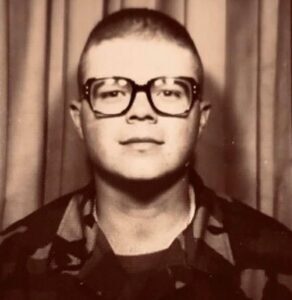

Private Freddy Rocha when assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division

Private Freddy Rocha when assigned to the 82nd Airborne DivisionFreddy arrived at Fort Bragg in February 1996. Because he was a new soldier fresh out of Jump School, the veterans subjected him and the other newly arriving soldiers to hazing. Freddy endured it all and became an integral member of the 82nd Airborne team. In April 1997, he deployed with his unit to Dharan, Saudi Arabia, where Khobar Towers had been bombed the year before. Freddy’s job was to provide security for a Patriot surface-to-air missile battery defending King Abdul Aziz Air Base. The deployment gave Freddy his first taste of an operational assignment outside the training environment, and he loved it. Even mundane tasks like donning his Mission Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP) gear, which is designed to protect soldiers from chemical and biological weapons, seemed exciting. He returned to Fort Bragg in August 1996 a motivated soldier.

Freddy made one additional deployment with the 82nd Airborne Division. This time it was to Belgium for training in early 2000. When he returned in March, he received orders to report to the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, located at Camp Hovey in South Korea. Because the unit operated near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea, Freddy could not take his family with him. This left his wife at home in charge of their two young children and their two older adopted children (a niece and a nephew). Knowing he would not see them again for a year, he said goodbye and boarded a plane for South Korea.

Although Freddy’s battalion was just fifteen miles from the heavily fortified DMZ and had to be always ready for a surprise attack from North Korea, his assignment proved uneventful until the day he was scheduled to depart. After celebrating the end of his tour with some buddies at bars in Seoul, he woke up in the barracks to his cell phone ringing. The call was from his wife asking him if he was going to war. Not knowing what had happened, he turned on the television and saw the second World Trade Center Tower being hit during the 9/11 terrorist attack on the United States.

Once word of the attack reached U.S. forces in South Korea, things moved quickly. Freddy’s unit, which had been exercising in the field without him, returned and Freddy was directed to immediately report to his defensive position with his weapon ready to repel any would-be attack. Unfortunately, he had already shipped all his belongings back to the States, including his uniforms and gear, because he had detached from his unit and was literally waiting to catch his flight home. Given the urgency of the moment, he hiked up the mountain to his defensive position carrying his weapon and live ammunition and wearing a t-shirt, flip-flops, cargo shorts, and a borrowed helmet. When his first sergeant saw him, he told him to get off the mountain, find a uniform, and get back into position ASAP. This Freddy did, and he found himself manning the position for eight days until things calmed down enough for him to return to the United States and rejoin his family.

Once back at Fort Bragg, Freddy received new orders to join Bravo Company of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, at Fort Lewis, Washington. He reported on October 11, 2001—exactly one month after 9/11—and promoted to sergeant as soon as he arrived. His unit was part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team. The Stryker was a new eight-wheeled armored vehicle with a crew of two and a troop compartment capable of carrying up to nine infantry soldiers. Freddy’s team was responsible for developing the tactics and standard operating procedures for deploying the Stryker with U.S. infantry units. That meant conducting training exercises to learn how to employ the vehicles with maximum effectiveness.

Freddy Rocha (right) in Iraq with one of his best friends, Jerry “Gonzo” Trejo (left)

Freddy Rocha (right) in Iraq with one of his best friends, Jerry “Gonzo” Trejo (left)Freddy’s situation changed when the Iraq War started in 2003. In November, he deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom to Kuwait with Bravo Company as part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team. He crossed with his company into Iraq in December to join the U.S. forces already in the country. The unit operated in northern Iraq, including in and around Mosul, employing the Stryker vehicle in combat operations for the first time. Freddy and the other members of his unit were tight and watched out for one another. In fact, his best friend, Gonzo, carried a photo of Freddy’s three-year-old daughter in his helmet because Freddy’s children were like family to him. Fortunately, Freddy’s company made it through the deployment without sustaining any casualties.

Freddy’s family was not as lucky. When he returned to Fort Lewis in August 2004, he and his wife separated and were divorced. Worse yet from Freddy’s perspective, his ex-wife was awarded custody of their kids. She did agree, though, not to move with the kids back to Southern California as long as Freddy was assigned at Fort Lewis. Seizing the opportunity, Freddy volunteered to stay with the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, for a second tour.

In June 2006, Freddy again found himself in Iraq as part of the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team and Operation Iraqi Freedom. This time he was assigned to the battalion headquarters’ mobile operations center and was responsible for defending the center in the event of an attack. This happened on January 27, 2007, after an Apache attack helicopter was shot down in the vicinity of Najaf.

When Freddy’s Stryker arrived on scene and lowered its ramp so Freddy and the other soldiers onboard could disembark, they found themselves in the thick of a firefight with Hellfire missiles screaming into action nearby. Freddy’s unit quickly joined Charlie Company of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, which was already in the fight, together with U.S. special operations forces and Iraqi Army soldiers, against hundreds of dug in Iraqi insurgents.

At one point after Freddy’s team set up the mobile operations center, Freddy heard the battalion commander radio the Charlie Company commander and ask for a situation report. The Charlie Company commander did not come to his radio. Instead, he could be heard shouting to his radio operator, “You tell him I’m in a firefight. I’ll update him when I can.” The fighting became so intense, Freddy promised God if he got out of it alive, he would quit smoking and marry his girlfriend. Enemy rockets flew everywhere while the special operations forces hammered away at the insurgents using a .50-caliber machine gun they salvaged from the downed helicopter. U.S. and British airpower joined the fight, and an AC-130 gunship devastated the insurgents with a barrage of fire from its rapid-firing cannons.

As the battle went on, Freddy’s sergeant major asked for help treating the wounded. Freddy volunteered because he had taken an emergency medical technician (EMT) course before the deployment. He grabbed a first aid kit and started to help, but he wasn’t prepared for the injuries he saw even though he’d seen casualties before and had not been affected by them. He collected himself by remembering he had a reputation to protect for being a tough soldier. Once he felt back in control, he returned to rendering aid.

The thirty-six-hour battle of Najaf was the fiercest action Freddy faced in Iraq, but other tough situations lay ahead. He lost a total of nineteen comrades during his brigade’s fifteen-month deployment, including some killed when improvised explosive devices destroyed the vehicles they rode in. Even Freddy was injured in a vehicle rollover accident.

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha with his daughter, Aleina, and his son, Fredo, when he returned from his second Iraq deployment

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha with his daughter, Aleina, and his son, Fredo, when he returned from his second Iraq deploymentWhen the 3rd Stryker Brigade Combat Team finally returned to Fort Lewis in September 2007, it received a hero’s welcome. Freddy’s girlfriend, his parents, and his children were all on hand to welcome him home and watch Freddy’s unit march by. It was the first time Freddy’s father had seen him in uniform, and it made Freddy feel proud.

Still, Freddy was tired. He’d been in the Army for twelve years and spent much of that time deployed, including twice to Iraq. So, when it came time to reenlist, Freddy asked for orders to a command at Fort Lewis that would not deploy. He also requested the colonel of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, administer his reenlistment oath. Both the colonel and Freddy found that funny because the colonel had “busted” Freddy in rank twice at Article 15 nonjudicial punishment proceedings while they were deployed in Iraq. But the colonel knew Freddy was a good soldier and believed in him, so he was happy to help Freddy reenlist. He also congratulated Freddy for surviving Iraq and for continuing with his Army career.

For the next three years, Freddy was assigned at Fort Lewis to Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, training National Guard units to deploy. On the job, he specialized in teaching short-range marksmanship. Off the job, he rehabilitated injuries he’d received overseas, got married, and earn his bachelor’s degree.

In March 2011, Freddy received orders to return to South Korea, this time as a platoon sergeant for one of two infantry companies assigned to the 1st Battalion, 72nd Armored Regiment, at Camp Humphreys. The concept was for the infantry companies, operating with their Bradley Fighting Vehicles, to learn to fight side-by-side with the tanks of the 72nd Armored Regiment. Freddy found the experience professionally rewarding and challenging. He motivated the soldiers in his platoon by reminding them they were training on ground fought for and won by the blood of U.S. soldiers during the Korea War just sixty years before.

Freddy returned to Fort Lewis in March 2012. At the request of his former battalion commander, he again took a job with the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, thinking it might be his last tour. He’d been tired ever since the battle of Najaf and was still having trouble dealing with his experience in Iraq. He tried to present an image of being a tough staff sergeant. After all, he’d been in combat and had earned the Expert Infantryman badge. But now, for his own well-being, he knew he had to change direction and find a job that involved helping people. His initial thoughts were to become a nurse. He just needed a sign before deciding to part company with the Army and retire. That sign came when he did not make sergeant first class.

Freddy officially retired on September 1, 2015, after serving twenty years and seven days on active duty. He then followed through on his goal of becoming a nurse by going to school to become a Certified Nursing Assistant. As part of his studies, he took a job at a nursing home to gain some practical experience. That experience taught him a nursing career would not be a good fit for him.

The transition to civilian life continued to prove difficult. All his life, he’d been an infantryman, and now that he was retired, suddenly everything he knew and valued was gone. A friend of his set up a meeting for him with a woman at the local Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) post and the woman asked him to bring his medical record. After the meeting, she helped him file a disability claim, which at the time he really didn’t understand. In fact, he felt like he was spiraling out of control. He visited the gravesite of one of his best friends killed in Iraq. He’d not attended any ceremonies honoring his fallen comrades in the past, suppressing any emotions he had by focusing on the mission at hand. Now it all came crashing down and he questioned how he could go on. He thought no one cared.

The turning point came one day when his car overheated. By chance, he pulled into the parking lot of VFW Post 2224 in Puyallup, Washington, and went inside to ask if he could use a hose to add water to his radiator. Carlos Alameda offered to help, and they began to talk. Immediately, Freddy knew Carlos understood him and what he was going through. Carlos invited Freddy to learn more about the VFW’s programs and showed him ways he could start helping other people through the VFW. It was just the medicine Freddy needed. Soon, the friendships he made at the Post started to fill the void he felt after leaving the Army. He felt like he had a purpose again.

Even after Freddy found the VFW, his life wasn’t all smooth sailing. It was, however, on the right trajectory. Although he divorced again in 2017, he remained on good terms with his ex-wife. Then, after his youngest daughter graduated from high school in June 2018, he moved to Springfield, Illinois. There he earned his master’s degree and accepted a position with the University of Illinois Springfield as an admissions counselor. He later transitioned to the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs as a full-time veteran service officer. Essentially everything Freddy now does centers around helping veterans and their families, and that is just the way he wants it.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired), for his twenty years of distinguished service to our country. Freddy willingly went wherever the Army needed him most, including two unaccompanied tours to South Korea and two combat deployments to Iraq. After successfully accomplishing all the Army asked of him, he returned to civilian life where he now devotes his time and energy to helping veterans and their families succeed. We thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Freddy’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

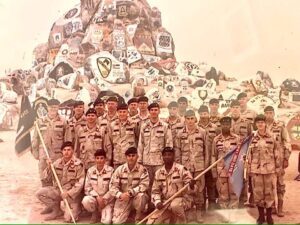

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha (second from right on first row) with other soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry

Staff Sergeant Freddy Rocha (second from right on first row) with other soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry The post Staff Sergeant Alfredo “Freddy” Rocha, U.S. Army (Retired) – 2 Iraqi Freedom Combat Deployments in a 20-Year Career first appeared on David E. Grogan.

October 15, 2025

Radio Telegraph Operator Second Class Leon Schiff, U.S. Merchant Marine – A Will to Serve During World War II

After the United States entered World War II, the American public rallied behind the war effort. Everyone contributed by recycling metals, accepting shortages of consumer goods so war materials could be produced instead, and buying war bonds. Even more significant, millions of men volunteered to serve in the armed forces. Yet not all who wanted to serve in the military could. Some had crucial jobs in agriculture and industry, so they could not be released to serve. Others like Radio Telegraph Operator Second Class Leon Schiff faced different barriers. Leon was so nearsighted, the military would not allow him to volunteer. Undeterred and committed to doing his part to bring about the defeat of Germany and Japan, Leon volunteered in 1944 to serve in the U.S. Merchant Marine—an underappreciated yet crucial component of the Allied victory in the war.

Leon was born in East Boston, Massachusetts, in 1925. He was the youngest of ten children and the son of a butcher. His father immigrated to the United States from England in 1903 after the London smog started causing him health problems. He sent for Leon’s mother and three older brothers in 1905 after he established himself in Boston and saved enough money for their passage. Leon’s remaining six brothers and sisters were quite literally born in their new home in the United States—Leon was the first and only one of the siblings born in a hospital.

After completing the ninth grade, Leon attended East Boston High School for his sophomore through senior years. Instead of gym class, he and the other boys participated in troop training. They even donned surplus World War I uniforms and joined boys from other schools marching through Boston to demonstrate their martial skills. Outside of school, Leon worked as a “soda jerk” at local pharmacy stores owned by his older brothers. During the summers, he took his skills to Winthrop and Revere Beach, where he worked with other boys serving soft drinks to people in dance halls taking refreshment breaks between songs.

Leon Schiff (small boy in bottom center) with his parents and seven of his brothers and sisters

Leon Schiff (small boy in bottom center) with his parents and seven of his brothers and sistersLeon turned seventeen in May 1942 and graduated from high school the following month. With the nation mobilizing in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor just seven months before, Leon’s first inclination was to enlist in the military. Unfortunately, he was very nearsighted, so the Army, Navy, and Coast Guard could not accept him. Upset but not discouraged, Leon attended Temple University in Philadelphia during the fall of 1942 and the spring of 1943 before hitchhiking to Canada to join the Canadian army to get into the fight. Again, he was thwarted because he did not want to risk losing his U.S. citizenship by taking an oath to Canada in order to enlist. Accordingly, he returned to Temple University for the 1943–44 academic year.

In the spring of 1944, Leon learned there was another way he could serve—the U.S. Merchant Marine. Merchant Marine civilian mariners manned the ships carrying millions of tons of supplies across the submarine-infested Atlantic and Pacific sea lanes to where they were needed most by the Allied forces fighting Germany and Japan. Closer to home, they manned the coastal freighters transporting goods between U.S. ports, always subject to the danger posed by German U-boats hunting them off America’s east coast.

Leon applied to the Merchant Marine in the late spring of 1944 and was accepted. He reported for boot camp at the U.S. Maritime Service’s training station at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, New York, immediately adjacent to the Coast Guard training station at Manhattan Beach. There he learned the basics of seamanship, including tying knots, ship driving, navigation, engineering, and cargo handling. He also took aptitude tests to see what positions he might be best suited for, such as cook, baker, engine room wiper or oiler, steward, hospital corpsman, or radio operator.

Based on Leon’s test results, he was selected to train as a radio operator. Accordingly, after completing boot camp, he and the other radio operator selectees were transferred to Gallops Island in Boston Harbor to attend radio operator school for twenty weeks. During the first week, Leon’s platoon of twenty men was assigned drudge work like cooking, cleaning, disposing of garbage, and performing other similar tasks. After a week of paying their dues, they began their formal radio operator training, joining two other platoons that had been training there for some time.

The schedule at Gallops Island was rigorous. Reveille woke Leon at 6:00 a.m. every weekday, followed by breakfast and exercise. Classes in radio theory and Morse code began at 8:00 a.m. and continued until 4:00 p.m., with a one-hour break for lunch. Every Friday, Leon and his classmates were tested on the week’s course material. If they failed, they repeated the week’s courses and retook the test at the end of the next week. If they failed a second time, they were dropped from radio operator training and returned to boot camp at Sheepshead Bay. To keep that from happening, the men helped each other learn the material in study sessions after the end of each workday. As a result, few failed the weekly tests.

The Sands Point was a powerful V4-M-A1 tug built in 1943. This photo is of the Trinidad Head, a similar V4-M-A1 tug. Source: U.S. Navy

The Sands Point was a powerful V4-M-A1 tug built in 1943. This photo is of the Trinidad Head, a similar V4-M-A1 tug. Source: U.S. NavyLeon was fortunate in that he excelled in both the radio theory course material and Morse code. Of the two, learning Morse code was more difficult because it was a skill some men had a knack for, and others didn’t. To successfully complete the training and earn his Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Second Class Radio Operator’s License, Leon had to be able to transmit and receive thirty words per minute, where a word consisted of a group of five short signals of light or sound. Leon caught on quickly because he recognized a rhythm in the transmissions, allowing him to increase his Morse code speed every week. He also had good role models in his instructors, who could send and receive up to sixty words per minute, so Leon knew thirty words per minute was certainly achievable.

By about the fifteenth week of the training, Leon had mastered the radio theory material and could send and receive over thirty words per minute in Morse code. Accordingly, he asked to take the next Monday off so he could take the Second Class Radio Operator’s License exam at the FCC office in Boston. When his instructors denied his request, Leon took matters into his own hands. The following Friday, he took the liberty boat to Boston and instead of returning to Gallops Island on Sunday morning as he was required to do, he stayed in Boston and took the FCC licensing exam on Monday. He then returned to the island on Monday afternoon.

Although Leon passed the exam and earned his Second Class Radio Operator’s License, he had defied his instructors and had to be held accountable. Accordingly, he was disciplined at an administrative procedure known as captain’s mast. His sanction was he had to take additional classes at night after the workday had ended, but Leon considered this a small price to pay now that he had his FCC license in hand.

Leon’s timing could not have been better. With the end of World War II on the horizon, the U.S. Maritime Service stopped sending radio operator trainees to Gallops Island. Leon and the other students were then transferred first to the radio operator training facility on Hoffman Island, near Staten Island, New York, and then back to the main training facility at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. An announcement followed that all radio telegraph operator trainees would be transferred to ships to serve as messmen, but Leon objected. He argued that since he already had his FCC license, he qualified to be assigned as a radio telegraph operator second class, which would make him a junior officer rather than an unlicensed seaman. The training staff agreed and, in May 1945, sent him to New Orleans shortly after Victory in Europe (VE) Day. There he joined the crew of the 186-foot seagoing tug Sands Point. The tug, which was built for the U.S. Navy in 1943 and operated by the Moran Towing Company under contract, had a crew of eighteen. As a radio telegraph operator second class, Leon was one of five officers onboard. The others were the captain, the first mate, the chief engineer, and the first assistant engineer.

As the Sands Point’s radio telegraph operator, Leon had his own stateroom, located immediately behind the tug’s radio room. This allowed him to be ready to send or receive radio messages at any time of the day or night, even when he wasn’t on watch. He also had to maintain the radio’s six large batteries, which powered the generator that ran the tug’s radio. Despite these responsibilities, Leon was called upon only three times to use his hard-earned Morse code skills. The most notable time involved the captain calling him to the pilot house to decipher a message a U.S. Army transport ship was sending using a flashing light. When Leon decoded the signals, he learned the crew of the Army transport did not know what their position was and was asking the Sands Point to tell them where they were. After Leon answered by providing the Army transport’s position, the Sands Point continued on its way.

Aside from the infrequent radio telegraph responsibilities, Leon’s principal duties involved standing watch in the tug’s pilot house and assisting the rest of the crew accomplish the tug’s towing missions. These missions primarily involved assisting tankers experiencing problems in the Gulf of Mexico as they ferried oil from Venezuela to the United States. The Sands Point rendezvoused with them wherever they broke down and towed them to a U.S. port on the Gulf Coast for repairs.

Leon and Eileen Schiff

Leon and Eileen SchiffLater that year, Leon and the Sands Point relocated to Galveston, Texas. In addition to continuing with its previous towing duties, it began making trips to the Wainwright Shipyard in Panama City, Florida, where it picked up new tankers that were no longer needed now that World War II was over. The Sands Point towed these tankers to Beaumont, Texas, and pushed them onto the mud flats for storage. The tankers were later sold at auction for pennies on the dollar to businessmen like Aristotle Onassis, who used them to build his postwar shipping empire.

Another postwar mission of the Sands Point involved towing cargo ships loaded with World War II surplus aircraft and vehicles into the deepwater areas of the Gulf of Mexico. Rather than selling the surplus items in the United States where they would flood the market, the U.S. government disposed of the items by shoving them overboard into the deepest part of the Gulf. The empty cargo ships were then towed to Beaumont’s mud flats, where they joined the tankers waiting to be auctioned off to the highest bidders.

Unlike on most ships, one highlight of life on the Sands Point was the food. Sometimes when the tug left Galveston, the cook would throw a net overboard to catch enough shrimp to feed the crew. Other fresh seafood was also plentiful, as were bacon and eggs and other staples. Even better, meals were available twenty-four hours a day. Aside from the food, Leon enjoyed sunning in the former gun mount tub on top of the pilot house and studying to become a pharmacist in hopes of following in his brothers’ footsteps. Rounding out his experience at sea, Leon only got seasick once when the tug rode out a hurricane in the deep water of the Gulf of Mexico. He felt sorry for the seamen that had to clean up the mess.

At the end of December 1945, Leon decided that since the war was over, it was time to go home. He returned to Boston and to his job working for his brothers at their pharmacies. He also took some pharmacy courses to prepare for the pharmacy exam. In 1947, his studying paid off when he passed the pharmacy exam and became a licensed pharmacist. That same year, he married, Eileen, his wife of sixty-three years before she passed away. Together they had a son, Jeff, and two daughters, Nancy and Lisa. Leon also eventually bought his brothers’ pharmacies and expanded to more locations in Boston until he finally got out of the pharmacy business in 1981. Now he is retired and living with one of his daughters on the Atlantic coast northeast of Boston.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Radio Telegraph Operator Second Class Leon Schiff for his service in the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II. Undeterred when doors closed to service in the military, Leon volunteered to serve on the ships supplying U.S. and Allied forces worldwide in their efforts to defeat the Axis. After many months of training, his service took him to the Gulf of Mexico, where he assisted ships at risk and enabled the U.S. postwar drawdown. We thank him for his service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Leon’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

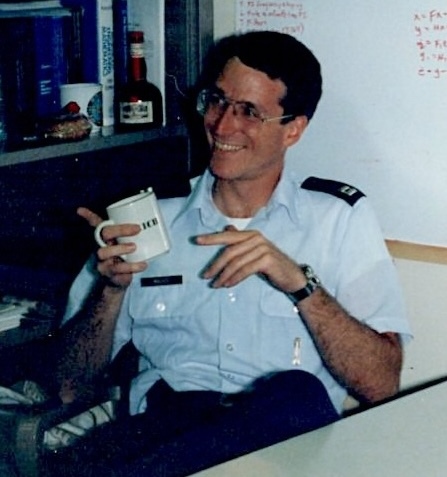

Leon Schiff

Leon Schiff The post Radio Telegraph Operator Second Class Leon Schiff, U.S. Merchant Marine – A Will to Serve During World War II first appeared on David E. Grogan.

September 10, 2025

Petty Officer Third Class Kimberly Yantis, U.S. Navy: Deploying on USS Boxer – “You Call, We Haul”

Every servicemember knows the GI Bill is a great way to help pay for an education. The benefits, however, are hard earned, sometimes involving long periods away from home and even deployments into harm’s way. Such was the case with Petty Officer Third Class Kimberly Yantis, U.S. Navy, who enlisted with a goal of using the GI Bill to help pay for her bachelor’s degree. She earned her benefits by participating in two deployments supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom and one to the Western Pacific, all the time working in extremely dangerous conditions on her ship’s flight deck. Now she channels her experience into her lifelong passion of helping veterans and their families in Central Illinois.

Kimberly was born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1983. She was the youngest of her parents’ three children and the only girl. She attended Southeast High School and spent her free time waitressing at local restaurants as soon as she turned sixteen. She also focused on her studies, qualifying her to graduate in December 2000, although she participated in the June 2001 ceremony with all her classmates who were on the normal graduation timeline.

After high school, Kimberly enrolled at Lincoln Land Community College and began taking classes in the fall. To help pay for books and tuition, she waitressed at Smokey Bones Bar & Fire Grill and worked a second job as a temporary employee for the Illinois Department of Family and Child Services. Her goal was to earn her bachelor’s degree, but her family could not afford it. Accordingly, in the spring of 2002, she looked to the Navy and the educational benefits it offered to help her achieve her goal.

Kimberly enlisted in the Navy’s Delayed Entry Program, which allowed her to continue working in Springfield until her active-duty report date in November 2002. When that date arrived, she took a bus to the Military Entrance Processing Station in St. Louis, where she passed her final physical and raised her right hand, swearing to support and defend the Constitution. Then, together with other new Navy recruits, she flew to Chicago to begin boot camp at Recruit Training Command Great Lakes, located just north of the city.

Kimberly Yantis’ company at boot camp. Kimberly is fourth from the left in the second full row from the bottom.

Kimberly Yantis’ company at boot camp. Kimberly is fourth from the left in the second full row from the bottom.Boot camp lived up to its reputation. As soon as Kimberly and the others got off the bus from Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, petty officers started screaming at them and getting in their faces. Kimberly was prepared for that, even cutting her hair short in anticipation of the stress-filled in-processing. Not satisfied, the Navy barbers chopped away at her hair anyway, making sure she did not miss out on the full recruit experience.

Despite the rigorous training schedule, Kimberly excelled. At nineteen, she was in good physical shape, so she did not find the running and other physical training difficult. Swimming, however, posed a bigger challenge. She and her fellow recruits spent a lot of time in the water learning the swimming and survival skills they needed to know but hoped never to use. On the positive side, Kimberly found the food good, especially since she was always hungry from all the physical activity and had limited time to eat her meals.

Two specific aspects of boot camp proved difficult. First, on Christmas Eve 2002, Kimberly had her wisdom teeth extracted. While the procedure ensured she would not have any problems with those teeth while deployed on a ship where a dentist might not be readily available, it made for an unpleasant holiday where she could only eat soft foods. Second, the ramp-up during the last week of boot camp was intense, preparing the recruits for their final training event. During this event, they had to stay up all night employing the swimming, firefighting, and other skills they learned during their eight weeks of training. After Kimberly passed the event, she felt ready for her first assignment on a ship at sea, which she already knew would be the USS Boxer (LHD-4).

With her parents in attendance, Kimberly graduated from boot camp on January 17, 2003. That same day, the USS Boxer deployed from San Diego on its way to the Persian Gulf carrying over 1,500 Marines and their equipment. Before Kimberly could join the ship, however, she had to complete airman apprentice training at the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC) in Pensacola, Florida. At NATTC, Kimberly learned the skills she would need for her assignment as an undesignated airman apprentice onboard the Boxer—a ship with an 844-foot flight deck from which helicopters and AV-8B Harrier jets could take off and land. Kimberly was considered “undesignated” because she had not yet been assigned a career field, or rating in Navy parlance. Accordingly, NATTC taught her the basic skills she would be expected to perform working on the flight deck of a ship. These skills included placing chocks under the wheels of helicopters and tying the aircraft down with chains, all the time with the helicopters’ rotors whirring above her head. She also received extensive firefighting training because fires onboard Navy ships loaded with aviation gasoline and ordnance could prove deadly if not quickly brought under control.

Kimberly completed her training at NATTC in February 2003 and went home to Springfield for some well-deserved leave. She coupled her leave with recruiting duty, which gave her some additional time at home. Then, it was off in March to the Boxer’s homeport in San Diego, where arrangements were made to fly her to the United Arab Emirates so she could meet the Boxer in the Persian Gulf. This she did in March 2003, shortly after the U.S. military and its allies commenced combat operations in Iraq on March 20 as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Kimberly and other sailors heading to the Boxer then helicoptered out to the ship, staying on an intermediate ship for a day en route. When they finally arrived onboard Boxer, it was operating off the coast of Kuwait.

Because USS Boxer was Kimberly’s first ship and the ship was involved in a war, she had to quickly acclimate to her new life at sea. As she expected, she was assigned to the Air Department, where she would work on the flight deck handling helicopters shuttling Marines and their equipment to and from the shore. Before she could do that, though, she had to pay her dues by working in the ship’s galley for ninety days, something all new junior enlisted sailors were expected to do. In the galley, she served food to other enlisted sailors and did general kitchen duties until her time was up. Then she reported back to the Air Department to begin working on the flight deck.

Kimberly Yantis (right) and another sailor wearing their blue shirt gear on USS Boxer

Kimberly Yantis (right) and another sailor wearing their blue shirt gear on USS BoxerWith helicopters landing and taking off, high winds blowing over the flight deck, and the Persian Gulf’s extreme heat, working on the flight deck was extremely dangerous. To ensure Kimberly learned her new responsibilities safely, she began by shadowing an experienced “blue shirt”—a sailor wearing a blue turtleneck shirt whose responsibilities included chocking and chaining H-60 Seahawk and CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters to the Boxer’s flight deck. Initially, Kimberly followed right behind her mentor, learning everything she needed to do around the helicopters. Once she had enough experience, she swapped positions with her mentor, and he followed behind her as she accomplished all the tasks he had formerly done. When Kimberly mastered all the tasks, she split duties with her mentor, with her mentor handling the far side of the helicopter and Kimberly handling the near side. After her mentor completed his work on the far side, he checked Kimberly’s work before signaling to the supervisory sailor wearing a yellow turtleneck that all was done. After about one month, Kimberly was on her own, a fully trained “blue shirt” responsible for safely handling helicopters on Boxer’s flight deck.

In late April, Boxer pulled into Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates to give the crew a week-long break. The break, though, was limited to an area on the pier known as “the sandbox,” where Kimberly and the rest of the crew could buy food and shop for souvenirs. Although it wasn’t as fun as touring an exotic port city, it was time off the ship and away from the grueling 24/7 operations at sea, which everyone appreciated. Afterwards, Boxer resumed her station in the northern Persian Gulf.

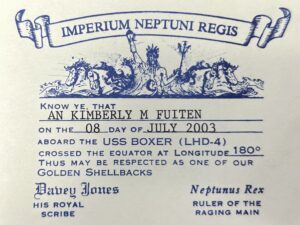

Near the first of July 2003, it came time for Boxer to head home to San Diego. On the way, the ship made port calls in Townsville and Sydney, Australia, giving Kimberly the opportunity to get off the ship and visit each city for a few days. The visit to Australia also meant she crossed the equator for the first time—a significant event in her career as a sailor. To mark the occasion, she participated in a “crossing the line” ceremony, where she transitioned from an untested “pollywog” to a “trusty shellback.” Because she also crossed the international date line at the same time, she earned the further distinction of being a “golden shellback.” She still has the certificate signed by Davey Jones and King Neptune recognizing her achievement.

USS Boxer returned to San Diego on July 26, 2003, and Kimberly’s mother welcomed her on the pier after she got off the ship. Under normal circumstances, the ship would have entered a reduced operational period to allow for post-deployment maintenance to be completed and the crew to spend some time with their families before beginning the next deployment cycle. However, with the Iraq War continuing, Boxer immediately began preparing to again deploy to the Persian Gulf.

On January 14, 2004—just six months after returning from its last deployment—Boxer again deployed with Marines from Camp Pendleton onboard in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The quick turnaround to transport the Marines to Iraq after the 2003 deployment validated the crew’s slogan for the ship, “You call, we haul.” Kimberly, now an experienced airman, continued with her blue shirt responsibilities on the flight deck across the Pacific Ocean and into the Persian Gulf. She also assumed new administrative responsibilities, helping her division’s chiefs process training and qualification documentation in anticipation of an upcoming inspection. The highlight of the deployment was Boxer’s port calls to Singapore; Goa, India; Sasebo, Japan; and Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Kimberly Yantis’ Golden Shellback certificate

Kimberly Yantis’ Golden Shellback certificateKimberly and the Boxer arrived back in San Diego on April 29, 2004. Expecting a more relaxed schedule having just completed two deployments to the Persian Gulf in less than eighteen months, Kimberly invited her brother, Mike, to live with her in San Diego. This worked well until Kimberly learned the Boxer was going to deploy yet again, this time to the Western Pacific, in April 2005. To prepare, Kimberly and the rest of the crew painted and performed maintenance on their spaces, making sure the ship was ready to deploy yet again. In addition, the ship spent time at sea maneuvering off the coast of California and conducting flight operations and beach assaults with embarked Marines. When departure time finally arrived, Mike returned to Springfield and Kimberly boarded the ship for her third deployment.

USS Boxer departed San Diego on April 29, 2005, heading west toward Sasebo, Japan. Kimberly was now a yellow shirt on the flight deck, supervising blue shirts handling the aircraft and communicating directly with the helicopters’ pilots. In addition, she had promoted to petty officer third class and was designated an Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Handling), together abbreviated ABH3. Despite these achievements, Kimberly’s deployment ended in Sasebo in May when she learned she was pregnant. The ship transferred her ashore and she flew back to San Diego, where she completed her four-year enlistment as an ABH3 with Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron 10 (HS-10). She was honorably discharged in November 2006.

After the Navy, Kimberly returned to Springfield, Illinois, to pursue her bachelor’s degree. Using the GI Bill, the Illinois Veterans Grant, and other benefits, she enrolled at Lincoln Land Community College and began taking classes in January 2007. Then in the fall, she enrolled at the University of Illinois Springfield, where she earned not only her bachelor’s degree in social work, but also her master’s degree in human services. She is currently working on a second master’s degree in public administration.

At the same time she was pursuing her degrees, Kimberly also worked full time. She began in October 2007 at the Sangamon County Veterans Assistance Committee (VAC), starting out as a clerk and transitioning to veterans service officer. Three years later, she left the VAC to become a veterans service officer for the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs, only to return to the VAC in October 2011 to serve as its superintendent. She continued in this role until early 2020, when she went back to the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs, where she serves as the central region supervisor.

Beyond her day job, Kimberly started her sixth year as the commander of Chatham-Auburn Memorial Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Post 4763 on July 30, 2025. She is the first woman to serve in the role and loves that she can continue serving the veteran community through her VFW post.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Handling) Third Class Kimberly Yantis for her wartime service in the U.S. Navy. Kimberly participated in three USS Boxer deployments, two of which took her into the Persian Gulf during Operation Iraqi Freedom where she worked on the flight deck helping Marines get into the fight ashore. She then returned to civilian life in Springfield, Illinois, where she has served veterans in both her professional and personal capacities ever since. We thank Kimberly for all she has done and wish her fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Kimberly’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chatham-Auburn VFW Post 4763 Commander Kimberly Yantis (right) with Adjutant Stephanie Wells (left)

Chatham-Auburn VFW Post 4763 Commander Kimberly Yantis (right) with Adjutant Stephanie Wells (left) The post Petty Officer Third Class Kimberly Yantis, U.S. Navy: Deploying on USS Boxer – “You Call, We Haul” first appeared on David E. Grogan.

August 20, 2025

Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Dean, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired) – Patrolling the Skies and the Seas to Keep Us Safe

Most of us work over forty years before retiring. Devoting that length of time to our careers makes finding a job we enjoy important. For some, it can take years of trial and error in different fields before finding the right fit. For Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Dean, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), the answer became clear long before he entered the workforce—he needed to be part of naval aviation. Getting there required hard work and dedication, but, once he achieved it, naval aviation brought him a lifetime of happiness, especially through the many outstanding people he met and worked with.

Tom’s father, Thomas M. Dean, Sr., enlisted in the Navy in October 1940 and was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked on December 7, 1941. During the war, he flew in Navy patrol aircraft in the Pacific theater. Afterwards, he stayed in the Navy and took an assignment at Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida, where he met Helen “Bonnie” Perelli. Bonnie’s fiancée, the radio officer on the troop transport SS Dorchester, had been killed in 1943 when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the ship. After his death, Bonnie moved from Philadelphia to Jacksonville to work in an aircraft factory and start her life over. Then she fell in love with Tom Sr., and they married in January 1945. They had their first child, Joan, in 1947.

The couple’s second child, Tom Jr., was born in 1958 when Tom Sr. was assigned as the maintenance chief for VF-124, a Navy fighter squadron based at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego, California. A year later, the family moved to Monroe, Louisiana, where Tom Sr. served for three years as a Navy recruiter. From there, they moved to Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, where Tom Sr. worked on a new type of long-range anti-submarine and reconnaissance patrol aircraft called the P-3 Orion. When Tom Jr. was four years old, he went with his dad to work and got to go on one of the new four-engine turboprop P-3s, where even the smell of the big airplane seemed inviting to him. Thus began Tom Jr.’s lifelong love of naval aviation.

In 1965, Tom Sr. moved the family to Naval Air Station Memphis in Millington, Tennessee, for his final tour. He retired there in 1970 as a master chief petty officer, the Navy’s highest enlisted rank, having served for thirty years. After he retired, the family stayed in Millington, which is where Tom Jr. (hereafter “Tom”) grew up and called home.

Tom attended Millington Central High School. He broke his leg during his sophomore year, which kept him out of most outside activities, especially sports. Once he recovered during his junior year, he began working at a local veterinary clinic, where the supervising veterinarian let him get involved in all aspects of animal care, including lab work, surgeries, and x-rays. One day when he was assisting the veterinarian with a Cesarian section on a cow, the Navy Blue Angels flew by low overhead as they practiced for their weekend air show in Memphis. At that moment, Tom knew he had to follow in his father’s footsteps and become part of naval aviation.

After graduating from Millington Central in 1976, Tom enrolled in the University of Tennessee (UT) Martin pursuing a degree in agriculture. When he learned he could participate in Navy ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps) at the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”), just an hour away in Oxford, Mississippi, he transferred there in 1977. Unfortunately, Ole Miss would not accept the class credits he had earned at UT Martin, so he had to start earning his degree from scratch.

Tom Dean standing under the wing of a P-3 Orion

Tom Dean standing under the wing of a P-3 OrionTom loved his time at Ole Miss. Because he was not part of the fraternity scene, the other members of the Navy ROTC unit became his closest friends. Together they learned what they needed to know to become Navy officers, and they formed strong bonds of friendship that continue today. Over the summers, the Navy sent Tom and the other ROTC participants, referred to as “midshipmen,” to operational Navy units to acquaint them with the Navy, its mission, and its sailors. Tom’s favorite trip was his first class midshipman’s cruise, where he got underway from Subic Bay in the Philippines for seven weeks with the USS Tarawa (LHA-1) on a cruise to the western Pacific Ocean. Not only did he have a front row seat to watch the ship’s sailors and Marines in action, but he also got to visit Hong Kong, South Korea, the Philippines, and Okinawa when the ship made port calls there. As someone who had loved everything Navy since he was four, he felt like a “kid in a candy store.”

When Tom graduated from Ole Miss with a bachelor’s degree in history in July 1980, he received his commission in the Navy as an ensign. Having achieved the necessary scores on the Aviation Selection Test Battery, he was also slated to begin training at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Knowing he could not meet the vision standards set for pilots, he set his sights on becoming a Naval Flight Officer (NFO). NFOs teamed with pilots on Navy aircraft, allowing the pilots to focus on flying the plane while the NFO handled the navigation, communication, and weapons systems. Given that Aviation Indoctrination School did not begin until October, Tom spent the summer at Naval Air Station Pensacola doing whatever he could to learn about being a new Navy officer. He even volunteered as a tour guide for people visiting the USS Lexington (CV-16), a World War II-era aircraft carrier used to train new pilots on how to make carrier landings and takeoffs at sea. Getting underway with the Lexington for day trips to train pilots was particularly meaningful for Tom because his father had served on board the Lexington before Tom was born.

Tom began NFO training at VT-10, the training squadron in Pensacola designed to turn new Navy officers into NFOs. The classroom work was grueling, and Tom had never studied so hard. Because he did not want to risk being dropped from the course, he studied every waking moment, taking a break only every now and then to see a movie over the weekend. Then it was back to the library or his room at the BOQ (bachelor officers’ quarters) to pick up studying where he left off.

In addition to studying, Tom got practical experience flying in the backseat of T-2 Buckeye jet trainers. On one such flight, he was taking notes and dropped his pen. No matter how hard he strained, he could not reach it because he was strapped into his seat. His instructor pilot heard his struggle over the internal communication system and asked what was wrong. When Tom told him he had dropped his pen and couldn’t reach it, the pilot said, “Why didn’t you tell me?” Then the pilot rolled the airplane upside down so the pen fell onto the canopy where Tom could reach it. Once Tom said he had it, the pilot rolled the plane again until it was right side up. Problem solved.

As graduation from NFO school approached, Tom and the other students submitted a wish list identifying their top preferences for the type of aircraft they would like to specialize in. Tom preferred the P-3 Orion he had visited with his dad. The Navy agreed P-3s were a good fit and sent Tom to Mather Air Force Base near Sacramento, California, for long-range navigation training.

Because the P-3 Orion’s mission involved hunting adversary submarines hiding beneath the ocean’s surface and conducting reconnaissance over vast swaths of the sea, P-3 NFOs had to navigate over the ocean without regard to ground formations for points of reference. Accordingly, Tom spent seven months learning dead reckoning and celestial navigation. Once he mastered those skills, the Navy designated him an NFO in August 1981 and authorized him to wear the wings of an NFO on his uniform. His training, however, was still far from over.

Tom next reported to Deep Water Survival Training, where he had to learn how to stay alive in the ocean in the event he had to bail out over water or his plane crashed at sea. During one training event, he and his fellow students were taken off the coast of California in a boat and told to jump into the water one-by-one wearing their flight suits, boots, and life jackets. The boat crew also warned the students not to pet any seals and to avoid sharks, sending shivers up Tom’s spine. After Tom hit the cold water, he treaded water waiting for a helicopter to come and pick him up. Suddenly, he felt something brush up against the exposed skin on the back of his neck. He reached back to see what it was and discovered it was kelp, which had become hooked to his life jacket. When the helicopter finally arrived and started to extract him by rope, the helicopter’s crew noticed the kelp was coming up with him. Not wanting the kelp in the helicopter, they started to repeatedly dip Tom in the water like a teabag. When the kelp finally fell away, they brought Tom aboard the helicopter, smiling at him because of the dunking ordeal they had just subjected him to.

The week following Deep Water Survival Training, Tom reported to Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) School in Warner Springs, California. The two-week school taught Tom and other new naval aviators how to handle being captured by enemy forces. When Tom and two others were captured by trainers posing as adversary forces, Tom accidentally knocked the hat off one of the trainers. He apologized but then found himself being roughed up by his captors. As his captors focused on him, the two aviators with Tom escaped. At the debrief at the end of the school, an instructor commended Tom for his quick thinking in knocking off his captor’s hat to allow his friends to escape. Tom sheepishly accepted the accolades, knowing his actions were an accident rather than intentional quick thinking.

After completing SERE School in October 1981, Tom reported to VP-31, the P-3 training squadron at Moffet Field where new and returning P-3 pilots and NFOs received their final flight training before reporting to their operational squadrons. Harking back to his time at VT-10, Tom studied nonstop to make sure he was ready to begin flying on P-3 missions in the fleet. Given his undergraduate major was history and he had taken no computer science classes at Ole Miss, he had to work hard to learn the P-3’s electronics systems. Oceanography also proved challenging because he had to learn the science of how sound propagates through water, an essential element of hunting submarines with sonar.

Tom completed his training at VP-31 in March 1982 and finally reported to his first operational P-3 squadron, VP-9, also located at Moffett Field. He was assigned as a navigator/communicator on P-3 flights, hunting for submarines and patrolling the waters off the U.S. Pacific coast. After two months, his plane deployed for six months to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa to fly missions in the western Pacific, including off the coast of the Korean peninsula and China.

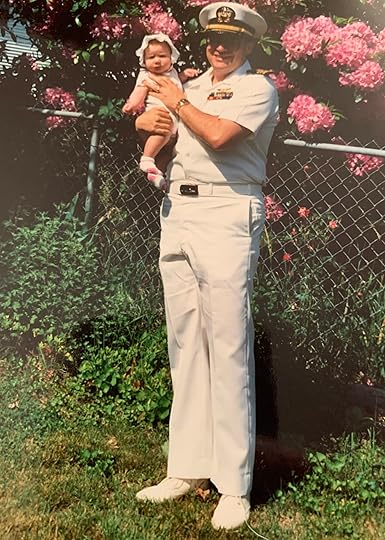

Lieutenant Commander Tom Dean holding his daughter, Lucy

Lieutenant Commander Tom Dean holding his daughter, LucyFor eight weeks of the Okinawa deployment, Tom’s plane was further dispatched to Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia in the middle of the Indian Ocean. From there the plane patrolled the waters off the coast of Somalia; landed and took off from airports in Mogadishu, Djibouti, and Oman; and flew missions all the way up the Persian Gulf to Kuwait, where Iranian anti-aircraft batteries locked onto them with their fire control radars. It even intercepted two Russian IL-38 May patrol aircraft. For three weeks of this time, the plane’s computer navigation system failed, and Tom had to determine the plane’s position and course using inertial navigation, dead reckoning, celestial navigation, and a sextant. His success validated the outstanding long-range navigation training he received at Mather Air Force Base and earned him the respect of his crew.

After Tom and the rest of his P-3’s aircrew returned to Okinawa and later to Moffett Field, they continued to hone their skills by searching for Soviet submarines in maritime patrol areas off the West Coast of the United States. To do this, the P-3’s crew dropped sonobuoys in the ocean to listen for any Soviet submarines in the area. If the sonobuoys found one, Tom’s P-3 crew would track it until they could hand it off to other U.S. units for continued monitoring. In the event of an armed conflict with the Soviet Union, Tom’s P-3 had the ability to attack and destroy any Soviet submarines it found.

As Tom gained experience, he also gained in rank and responsibility. After promoting to lieutenant (junior grade) and serving eighteen months as the navigation/communications officer on his flights, he qualified as his plane’s tactical coordinator/mission commander (TACCO). He also became the squadron’s “blue card” navigator, qualified to evaluate other navigators joining the squadron. He subsequently promoted to lieutenant in May 1985 and continued in his TACCO role for the remainder of his time with VP-9.

After one of Tom’s missions as TACCO where his P-3 located and tracked a Soviet ballistic missile submarine, the plane returned to Moffett Field at 7:00 a.m. and prepared to land. As it came in for its final approach, Tom could see people driving in bumper-to-bumper traffic along California Highway 101, unaware of the plane’s mission or how it was helping keep them safe. It made Tom feel good to be part of his squadron’s team of professionals and know their efforts were important.

In September 1985, Tom transferred back to VP-31 to become an NFO instructor. As an instructor, Tom flew on monthly long-distance navigation training missions that often included visits to Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. He especially enjoyed his visits to the Philippines because he loved meeting the Philippine people and learning about their culture. The most important aspect of his instructor tour, though, was that he met Terry Kaiser at a bar celebrating her brother’s birthday in October 1986. Terry’s work at NASA in Imagery Technology impressed Tom, and they started dating.

When it came time to transfer from VP-31 in February 1988, Tom wanted to try something new. He asked his detailer if he could get a tour on an aircraft carrier, and his detailer obliged, sending him orders to the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CVN-65). As the Enterprise was deployed at the time, Tom joined the ship in the North Arabian Sea. He was assigned as the OX Division head in the ship’s Combat Information Center, which managed the ship’s assets responsible for defending against adversaries.

Arriving onboard the Enterprise was like entering a new and unfamiliar world. Having spent six years on P-3 patrol aircraft, Tom knew little about life on board ships. It took him a full three months before he felt comfortable with the transition, all the time soaking up information from the many shipmates he worked with. In fact, everyone he met went out of their way to make him feel welcome and teach him what he needed to know to succeed.

One of the shipboard traditions Tom experienced was the “crossing the line” ceremony. That happened when the Enterprise crossed the equator to make a port call in Mombasa, Kenya. Because Tom had never crossed the equator on a ship before, he was considered an uninitiated “pollywog.” Accordingly, he and other pollywogs like him had to prove themselves worthy in a raucous initiation ceremony. At the end, “King Neptune” found him worthy and designated him as a trusty “shellback.” Tom still has the certificate signed by King Neptune documenting his achievement.

In April, hostilities broke out with Iran after a frigate, the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) was severely damaged after striking an Iranian mine in international waters in the Persian Gulf. As part of the U.S. response, code named Operation Praying Mantis, planes from the USS Enterprise retaliated against Iranian navy speedboats and an Iranian frigate, causing significant damage. Tom’s role involved tracking the fuel status and refueling requirements for the dozens of USS Enterprise strike aircraft flying sorties against the Iranian targets. He also ensured Navy in-air refueling tankers, which refueled the strike aircraft throughout the day, got the aviation gas they needed from much larger Air Force KC-10 tankers circling in the area.

Tom and the USS Enterprise returned to Naval Air Station Alameda, California, on July 2, 1988. Six months later, in January 1989, he and Terry married. Then it was time for the Enterprise to begin a series of exercises to prepare for its next deployment—an around-the-world cruise. The ship began the cruise on September 17, 1989, heading west across the Pacific and making port calls in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore.

Throughout this time and for the remainder of the cruise, Tom monitored the aviation fuel consumed by the squadrons operating from the ship. When it reached a certain level, he arranged for supply ships to come alongside the Enterprise while underway to replenish its aviation fuel supply. He also authored several critical daily reports for the ship’s operations department, helping align the department’s many functions into focused action. In the little free time he had, he went out on the carrier’s flight deck during flight operations, studying the launching and recovery of the ship’s aircraft and observing the careful choreography of the many sailors that made it happen.

After crossing the Indian Ocean, the Enterprise operated in the Arabian Sea about 100 miles south of Iran, where tensions remained high. Despite this, the ship’s executive officer decided the crew had been working hard and deserved a “steel beach” picnic, which was a giant cookout on the carrier’s flight deck. Tom could not participate in the picnic because he was standing watch as the ship’s tactical action officer (TAO), which meant he had the authority to employ the ship’s defensive weapons systems in the event of an impending attack. During Tom’s TAO watch, another U.S. ship operating in the Arabian Sea, the USS Bagley (FF-1069), reported an Iranian fire control radar had locked onto the ship. Then, radar detected two Iranian F-4 Phantom jets heading directly toward the Enterprise.

Tom Dean standing next to a FedEx cargo plane

Tom Dean standing next to a FedEx cargo planeTom knew he had no time to waste—he called the Enterprise to general quarters. Sailors on the flight deck started throwing the grills overboard to prepare the ship to launch two F-14 Tomcat fighters that were on a thirty-minute alert. The F-14s launched and intercepted the Iranian aircraft, causing them to stay clear of the Enterprise and deescalating the situation. The Enterprise’s executive officer, however, was furious because Tom’s call to general quarters brought a sudden end to the ship’s steel beach picnic.

The next day, the admiral commanding the battle group consisting of the USS Enterprise and numerous other warships directed Tom to report to the admiral’s conference room to explain what happened. After the briefing, Tom waited in the passageway outside the conference room to learn his fate. When the admiral emerged, he pulled Tom aside and said, “If I had been in your shoes, I would have done exactly the same thing.” Immediately, a huge weight lifted off Tom’s shoulders, and he could breathe again. Although the executive officer was still upset, Tom had done the right thing. He also appreciated that the admiral had supported him and taken the time to let him know. The Navy let him know he was doing a good job, too, promoting him to lieutenant commander in January 1990.

After its operations in the Arabian Sea, the Enterprise continued its way westward, crossing the Atlantic Ocean. After some final port calls in Brazil and the Caribbean, it pulled into its new homeport at the Navy Base in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 16, 1990. Tom didn’t stay with the ship long thereafter, instead heading on a temporary assignment with Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing 10 at Moffett Field, where he worked with weapons system simulators. Then in July, he and Terry moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where Tom began a year of study at the prestigious Naval War College. Not only did he earn his master of arts degree in defense and strategic studies, but he also earned a separate master’s degree in management on his own from nearby Salve Regina University. As if that wasn’t enough, Tom’s and Terry’s first daughter, Lucy, was born in February 1991.

Tom graduated from the War College in June 1991 and reported once again to VP-31 at Moffett Field in California. After completing a P-3 refresher course, he reported in December 1991 to Naval Air Station Barbers Point in Hawaii for his department head tour with VP-1. His family, which included the addition of their second daughter, Lizzie, in 1995, lived in Navy housing on Ewa Beach, just a few miles from Barbers Point. This was convenient because Tom also served as the squadron’s assistant operations officer, which required him to be available on short notice to do things like oversee the evacuation of all squadron aircraft to the mainland, which happened in September 1992 when Hurricane Iniki threatened Oahu.

Tom also continued serving as a TACCO and mission commander for VP‑1 on P-3 flights around the Pacific theater, including during a six-week deployment to Howard Air Force Base in Panama to conduct counter-drug smuggling operations with the Coast Guard. On one mission flying out of Panama, Tom’s plane directed a rescue helicopter to a badly burned civilian mariner at sea, saving the mariner’s life. After the assignment in Panama ended, Tom returned to Hawaii and remained with VP-1 until he transferred to work on the staff of Commander, Patrol Wing Pacific in 1995. There he served as the training officer responsible for weapons and cockpit simulators.

When it came time for Tom’s next set of orders in 1997, he learned he would likely have to go to another aircraft carrier. Although he loved his time onboard the USS Enterprise, he did not want to do that again, especially now that he had a young family he wanted to spend his time with. Accordingly, he took the opportunity to retire offered by the Temporary Early Retirement Authority, or TERA, put in place to help draw down U.S. military forces after the end of the Cold War. Tom officially retired from the Navy in February 1997 after seventeen years of distinguished military service, during which he amassed close to 4,000 flight hours as an NFO.

After Tom retired, he, Terry, and their two girls moved to Memphis, Tennessee. There Tom began a twenty-five-year career with FedEx as an aircraft flight dispatcher in the company’s global operations center. He loved the job because it encompassed all the skills he learned in the Navy and kept him involved in aviation. In fact, his job required him to take frequent rides on FedEx planes to maintain his aircraft flight dispatcher qualifications. Tom also maintained ties to his military roots by becoming an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). To this day, what Tom values most about his service was the opportunity to work with the many outstanding Navy professionals, both at sea and in the air, keeping America safe by doing a job they all believed in.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Dean, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), for his years of distinguished service to our country. From patrolling the oceans for Soviet submarines to ensuring aircraft from the USS Enterprise were able to protect U.S. forces from Iranian aggression, Tom always answered our nation’s call. We thank him for his many years of selfless service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Tom’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Tom and Terry Dean with their youngest daughter, Lizzie (left)

Tom and Terry Dean with their youngest daughter, Lizzie (left) The post Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Dean, Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired) – Patrolling the Skies and the Seas to Keep Us Safe first appeared on David E. Grogan.

July 16, 2025

Specialist Jeremy Carroll, U.S. Army – From Training Troops at Fort Irwin to Collecting Intelligence in the Iraq War

America’s fighting forces are the best in the world. They earned that distinction by training day in and day out, preparing them for victory on the battlefield. Specialist Jeremy Carroll, U.S. Army, knows the importance of training better than most because he trained thousands of soldiers destined for combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. When his own turn came to deploy in 2003, he saw firsthand the benefits of realistic training and incorporated his experience into the lessons he passed on to others. As a result, his service had a positive impact on countless U.S. Army units and soldiers deployed around the world.

Jeremy was born in 1980 in West Berlin, an island of democracy surrounded by communist East Germany. His father was a U.S. Army staff sergeant stationed there during the Cold War with the Soviet Union. After West Berlin, Jeremy moved with his parents and older brother to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where Jeremy’s father was a drill sergeant. When Jeremy was almost six years old, his father left the Army and moved the family from Fort Knox to Springfield, Illinois, where they put down permanent roots.

Jeremy Carroll (white shirt) surrounded by his father (left), brother (right), and late grandfather (bottom right). All are veterans.

Jeremy Carroll (white shirt) surrounded by his father (left), brother (right), and late grandfather (bottom right). All are veterans.Jeremy attended Lanphier High School where he ran cross country and wrestled until his senior year. To earn spending money during the summers, he detasseled corn on nearby farms. He also started planning his future, which, by the time he was a junior, he knew would include a stint in the Army. By joining the Army, he would be following not only in his father’s footsteps, but also in the footsteps of his older brother, his maternal and paternal grandfathers, and numerous other relatives. The Army also offered education benefits to allow him to pay for college, which he intended to enroll in after serving out his enlistment.

To follow through with his plan, Jeremy visited an Army recruiter during his senior year. He told the recruiter his older brother was a cryptologic linguist who analyzed and interpreted foreign language communications, and he wanted to do that, too. Because Jeremy spoke some Spanish, the recruiter said he could make it happen and guaranteed Jeremy a slot in the cryptologic linguist MOS (Military Occupational Specialty). However, because Jeremy was only seventeen, his parents had to give their written permission for him to enlist. They did so after he graduated from high school in June 1998.