Scott Timberg's Blog

December 13, 2019

Scott Timberg Has Passed Away

I’m so sorry to report that our good friend Scott has passed away this week. Scott’s family and friends have set up a GoFundMe page. Please consider contributing. More later.

June 4, 2019

Ojai Music Festival and JACK Quartet

Photo: Timothy Norris

Photo: Timothy NorrisONE of the best things about spring in Southern California is the Ojai Music Festival, which runs this Thursday to Sunday. I’m looking forward to this year’s festival, which was programmed by soprano Barbara Hannigan. Ojai is – in my two decades of attending most years – always good and sometimes great. It reminds us that classical music, for all the enduring work of the past, is a living art, unfolding in our own time.

The 2019 installment is especially appealing because it’s got a healthy serving of jazz – a number of pieces by longtime downtown innovator John Zorn, as well as young composer/ percussionist Tyshawn Sorey. There are some short pieces by John Luther Adams, one of our day’s finest composers and one, like the festival itself, attuned to the outdoors. And the group that’s playing a lot of these pieces – the New York-based JACK Quartet – is clearly one of the bright lights of the new-music scene. (The group made a very good impression at a festival preview event in Los Angeles a few months ago, explaining things like temperament and intonation in an accessible way, and playing examples with a startling kind of eloquence and control.)

JACK Quartet (Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)

JACK Quartet (Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)The other day I spoke to Jay Campbell, the group’s cellist. Campbell grew up in the Bay Area, skateboarding and listening to a wide range of music, from indie rock to the free-jazz improvisation of the Art Ensemble of Chicago. “So it was kind of a logical move,” he says, “to be interested in what was happening now in classical music.”

He was lucky enough to meet John Adams, and played a piece of his music while still a young kid. “It kind of blew my mind that a composer could be not dead,” Campbell says. He realized that all of the composers he played had been alive at some point; it reframed his sense of where the music came from. Later he discovered Ligeti and the Minimalists.

This didn’t, though, make him any more attentive a student. He spent most of his early years, he says, “never, never practicing.” When he applied to study at Julliard, he didn’t get in and felt unmoored. After a year, he applied again, got in, and decided to take things seriously for a change. “So I basically locked myself in a practice room for eight hours a day, for four years,” he says. At night he’d play new-music gigs around New York and absorbed as much as he could.

Discovering the work of Austrian microtonalist George Friedrich Haas, and the school of spectral music Haas is associated with, made a strong impression on Campbell. “It change my life, musically,” he says, orienting him to “a more sensual sound,” and turning him on to the power of the drone and the complexity of intonation.

These days Campbell and his colleagues in JACK Quartet often work on world premieres. “How can I bet a better collaborator with living composers?” he asks. “I find that to be the most exciting stuff. To be at a world premiere of a piece, with someone you collaborated with… It’s very different than playing a Bach suite.” Campbell also plays the core repertoire with a piano trio. But with new music, “It expands what is possible with my instrument. It makes me feel a little bit expanded.”

I asked Campbell to describe a couple of the pieces he’s playing at Ojai.

On Sunday morning JACK will perform the world premiere of a string quartet by Catherine Lamb. “She’s a composer of most intonation-based, droney, slowly developing music – it’s about the sounds behind the sounds.” The piece begins with all four musicians holding the same tone, a C natural. “It depends on the music unfolding slowly over time; it’s intense and meditative at the same time.”

On Friday night, Campbell and the JACK lads will perform Schoenberg’s second quartet. He calls it, “very deep on so many levels. You feel a lot of his angst and conflict at the time: His chamber symphony had just been premiered, and was a total disaster.” Partway into the piece, it adds a free soprano part – sung by Hannigan – and an old German song from the plague years. (Only an upbeat Californian like Campbell could describe this piece as “really fun.”)

Overall, he’s excited about Ojai and was pleased with what he saw when he visited last year. He was struck by “how open and interested the audience is, and how willing they are to be taken on a journey. The fact that they’re game for that is really cool.”

Campbell, – who also spoke about the liveliness of the new-music scene in LA and elsewhere, as well as the persistence of Minimalist composers – mentioned something that keeps coming up among my music friends: The growing interest in site-specific, immersive and very long pieces of music in a world that constantly seems to be speeding up. (We spoke a bit, for instance, about Max Richter’s Sleep.)

The sensory overload, always-on tempo of contemporary culture has led a lot us to crave more meditative and gradually unfolding work – and this is true for musicians as well as audiences. “I find something very ecstatic about that music – the way it unfolds over a very long time,” Campbell says. “That’s something that other cultures have known” for many centuries. Now we in the secular, post-industrial West are kind of waking back up to music as ritual.

See you in Ojai!

June 3, 2019

What’s in a Name?

This is the second in a series of posts by guest blogger Milton Moore, a longtime music critic who has covered a wide array of genres.

* * *

When Scott invited me to write about the new music I was sharing with him, we immediately faced a dilemma: What to call this stuff?

Some of this might slip into the classical bin, but it doesn’t really target the Mozart audience or fit in standard concert venues. Some of this fare gets called world music, but these days, that seems just a lazy catch-all for music from far away that found you on the internet. Some of this music is saddled with the goofy tag “folktronica,” but I pledge never again to type that word, out of respect for Bartók and the other field recording pioneers who began this mining of traditional veins.

Most of these composers seem like variations on the singer-songwriter genre, more in line with a lineage from the Beatles to Bang on a Can and the Philip Glass Ensemble than the lineage of Beethoven to Bernstein. Most perform their own compositions and many sing. It’s not an exclusive club – in fact leaps of technology have opened the doors wide – but it’s one that’s hard to define.

Labels matter. A few years back, I reviewed a concert by the string quartet Brooklyn Rider, a program that culminated with the quartet scaling Beethoven’s towering Opus 131. But that chamber concert also featured the musicians standing to sing a Colin Jacobsen strings-and-voice transcription of a Joao Gilberto song. I called the performance “alt-classical,” a label I just plucked out of the air only later to find that’s a term many detest. I still think “alt classical” is descriptive, but we all respond to peer pressure to some degree. At an NEA critics’ workshop I attended, music historian and critic Joe Horowitz was campaigning the label “post classical,” but we all pushed back – our editors would never buy that.

Labelling music can be a challenge, but never more so than today. We live in the most exciting period for music I can remember. If we exclude industrial music, the hiphop and the anthemic ballads and the crooners in cowboy hats that are marketed by the music industry, we can find so much new music aboil with Big Bang energy.

No single term can define what’s happening. Today we have musicians who are equally at home performing in a pub or in a concert hall. Some are former rockers with a keyboard, and some are conservatory grads with a cello and a computer. It’s a polyglot brood spawned of such disparate sources as electronic dance music and Yale programs in composition. What they share is the urge to put aside pretension and formalism and just make music.

To define this stuff, I could just revert to the null hypothesis: Is it popular music? No, it’s certainly not popular. But promoting “unpopular music” is a non-starter for all the obvious reasons. Perhaps the best null name is owned by a British production company and label: Nonclassical. You sort of know it when you hear it.

Oddly enough, the inverse of the oft-reported death of classical music seems to fuel much of this wave of creativity. The world has a glut of highly trained musicians. Conservatories are creating more skilled performers and composers than ever before – far more instrumentalists than there are seats available in established orchestras. Many of these new genre musicians are offspring of the Brian Eno crossover of the Seventies, but just as many hold masters’ degrees in music performance and are creating new outlets for their talents.

Most of this music coming at us from the margins is short-form. The composers on the techno-Eno axis are accustomed to brevity. The more classically aligned composers who hope to get their music performed by an orchestra know that music directors are much more likely to program a 10- or 12-minute piece than a long, multi-movement opus from a contemporary composer, atuned their audiences’ tolerance for the unfamiliar.

Many of these musicians share a willingness to follow new directions for familiar material, leaving the confines of classical forms behind. They draw on folk roots from their heritage or create mashups of eras and genres and instrumentation. The classical audience, having recovered from a couple generations of serialism, is less averse to the new, and the works of musicians such as John Williams and Kurt Weill have been able to gate-crash the or

chestral repertoire.

All music speaks for itself, if you are open to actually hearing it. Why would we need to label it all?

– Milton Moore, mmoore3@gmail.com

May 12, 2019

Time Pauses For Valentin Silvestrov

A quarter century ago, a New England journalist named Milton Moore turned me – a lover of rock and jazz without much interest in music before Elvis Presley and Charlie Parker – on to Schubert, late Beethoven, and The Well-Tempered Clavier.

Milton, who has been reviewing music, classical and otherwise, since the ‘70s, today starts a more-or-less monthly column about contemporary and “alternative” classical music. At least for the first few installments, he will be concentrating on composers whose work deserves more attention. His first installment is on the music of Valentin Silvestrov.

* * *

You’re sure to find a comfortable spot to nestle into the sprawling body of work by Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov. His compositions range from the conventionally outrageous to the outrageously conventional, and few composers today write with more transporting and direct lyricism.

The 81-year-old Silvestrov has published more than 100 works, including 28 for orchestra (six symphonies), 20 chamber works, and song cycles, piano works and large choral works. More than 36 CDs of his works have been recorded, including nine on the irreplaceable ECM label.

Silvestrov was a mid-Sixties bad boy, much like Russia’s Alfred Schnitkke, writing spare, percussive, and antagonistic orchestral works that were suppressed in his own country while being praised in the West, his prickly Symphony No. 3 winning the 1967 Koussevitzky Prize.

Then, in the Seventies, Silvestrov changed. He began to write what he called “kitsch music.” Musicologist and composer Svetlana Savenko writes that Silvestrov coached his performers that “it should be played in a very tender and heartfelt way” and directed the baritone performing “Silent Songs” cycle “to sing as if singing to himself.” This calm and utterly introspective approach is hardly the stuff hits are made of, yet it is uniquely affecting.

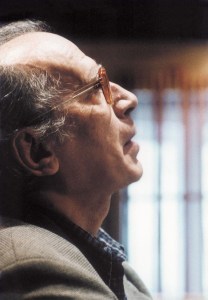

Robert Masotti/ECM

I can’t think of a living composer who writes more consistently entrancing songs and piano works spun of long, often indefinite melodic lines, dreamlike and drifting like watching smoke from a fire’s dying embers. He has titled several works as postludes, reflecting his elegiac and nostalgic sense that he stands amid the detritus of artistic eras. Alfred Schnittke surveyed that wreckage and despaired. Silvestrov instead sings hymns to it, hazy recollections of a reverence for the fading memories.

Henry James mused that as we think of our pasts, we do not recall events, but our memories of events, multilayered and changeable with each retrieval and each return to storage. So it is with Silvestrov’s nostalgia, his affection for nostalgia itself. Silvestrov shares with Schnittke a commitment to postmodernism, a belief that every musical inventor has expounded every musical concept for so many centuries that allegiance to any style is marginalizing. Schnittke called his approach “polystylism.” Silvestrov calls his “metamusic,” the cosmos of musical ideas.

In 1984, Schnittke famously wrote that learning Serialism was a rite of puberty for a young free thinker of the Sixties, “the unavoidable proof of masculinity through Serial self-denial.” He added, “Having arrived at that final station, I decided to get off the already overcrowded train. Since then, I have tried to proceed on foot.” Silvestrov rephrased the same sentiment: “The most important lesson of the avant-garde was to be free of all preconceived ideas – particularly those of the avant-garde.”

Silvestrov’s avant garde period is not to be dismissed. From it evolved his grand symphonies – Nos. Four to Eight – that are vaster, with denser orchestration and more obvious thematic cores than his Third. Each of these rich sonic events opens with a dissonant catastrophe and spans one long arc, each drama opening as if at the conclusion, the smoking rubble of a ruined soundscape, ominous and uneasy. From these growling sonic tectonic plates, haunting melodic motifs rise and sink back into the mass. His Fifth Symphony is the finest of the lot, its melodic motifs that rise from darkness in low brass stirringly Wagnerian in both character and soaring reach.

But it is Silvestrov’s song cycles and piano works, his kitsch, that I return to again and again. His “Silent Songs” were the first in this series of simple works that have that Schubertian ability to distort time. You find yourself holding your breath. Even his most direct melodies are fleeting, as if glimpsed from a train window. British critic Malcolm MacDonald wrote that Silvestrov writes not the lament itself “but the lingering memory of it.”

To sample this music, I suggest three discs.

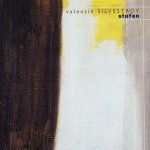

First, the song disc “Stufen” with pianist Alexei Lubimov and mezzo Jana Ivanilova, on the hard to find Megadisc label that can be streamed for pay at Amazon or free at Spotify, settings of poetry from the likes of Keats and Pushkin. The echoing sonic ambience adds a shimmering haze to the nostalgia, a disc so intimate the listener feels almost an eavesdropper, as you can hear on “Elegy.”

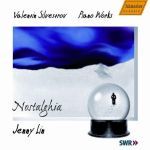

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

In recent years, Silvestrov has expanded his sonic scale with choral compositions rooted in Orthodox tradition and advancing the composer’s gift for achingly evanescent melodic constructs. ECM has released a pair of recordings with Mykola Hobdych leading the Kiev Chamber Choir in these a cappella gems, the first of which BBC critic Michael Quinn called simply “ravishing.” Sample the Ave Maria, you’ll agree.

Silvestrov’s music could be grouped with Pärt and Górecki, but that misrepresents his unique approach to melody. He is far less given to minimalist sequencing than these other Eastern mystics. Silvestrov’s music is perhaps anachronistic, but the question isn’t, why do we need more traditionally beautiful tonal music? The question should be, why would you turn away from this?

– Milton Moore

Time pauses for Valentin Silvestrov

A quarter century ago, a New England journalist named Milton Moore turned me – a lover of rock and jazz without much interest in music before Elvis Presley and Charlie Parker – on to Schubert, late Beethoven, and The Well-Tempered Clavier.

Milton, who has been reviewing music, classical and otherwise, since the ‘70s, today starts a more-or-less monthly column about contemporary and “alternative” classical music. At least for the first few installments, he will be concentrating on composers whose work deserves more attention. His first installment is on the music of Valentin Silvestrov.

* * *

You’re sure to find a comfortable spot to nestle into the sprawling body of work by Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov. His compositions range from the conventionally outrageous to the outrageously conventional, and few composers today write with more transporting and direct lyricism.

The 81-year-old Silvestrov has published more than 100 works, including 28 for orchestra (six symphonies), 20 chamber works, and song cycles, piano works and large choral works. More than 36 CDs of his works have been recorded, including nine on the irreplaceable ECM label.

Silvestrov was a mid-Sixties bad boy, much like Russia’s Alfred Schnitkke, writing spare, percussive, and antagonistic orchestral works that were suppressed in his own country while being praised in the West, his prickly Symphony No. 3 winning the 1967 Koussevitzky Prize.

Then, in the Seventies, Silvestrov changed. He began to write what he called “kitsch music.” Musicologist and composer Svetlana Savenko writes that Silvestrov coached his performers that “it should be played in a very tender and heartfelt way” and directed the baritone performing “Silent Songs” cycle “to sing as if singing to himself.” This calm and utterly introspective approach is hardly the stuff hits are made of, yet it is uniquely affecting.

Robert Masotti/ECM

I can’t think of a living composer who writes more consistently entrancing songs and piano works spun of long, often indefinite melodic lines, dreamlike and drifting like watching smoke from a fire’s dying embers. He has titled several works as postludes, reflecting his elegiac and nostalgic sense that he stands amid the detritus of artistic eras. Alfred Schnittke surveyed that wreckage and despaired. Silvestrov instead sings hymns to it, hazy recollections of a reverence for the fading memories.

Henry James mused that as we think of our pasts, we do not recall events, but our memories of events, multilayered and changeable with each retrieval and each return to storage. So it is with Silvestrov’s nostalgia, his affection for nostalgia itself. Silvestrov shares with Schnittke a commitment to postmodernism, a belief that every musical inventor has expounded every musical concept for so many centuries that allegiance to any style is marginalizing. Schnittke called his approach “polystylism.” Silvestrov calls his “metamusic,” the cosmos of musical ideas.

In 1984, Schnittke famously wrote that learning Serialism was a rite of puberty for a young free thinker of the Sixties, “the unavoidable proof of masculinity through Serial self-denial.” He added, “Having arrived at that final station, I decided to get off the already overcrowded train. Since then, I have tried to proceed on foot.” Silvestrov rephrased the same sentiment: “The most important lesson of the avant-garde was to be free of all preconceived ideas – particularly those of the avant-garde.”

Silvestrov’s avant garde period is not to be dismissed. From it evolved his grand symphonies – Nos. Four to Eight – that are vaster, with denser orchestration and more obvious thematic cores than his Third. Each of these rich sonic events opens with a dissonant catastrophe and spans one long arc, each drama opening as if at the conclusion, the smoking rubble of a ruined soundscape, ominous and uneasy. From these growling sonic tectonic plates, haunting melodic motifs rise and sink back into the mass. His Fifth Symphony is the finest of the lot, its melodic motifs that rise from darkness in low brass stirringly Wagnerian in both character and soaring reach.

But it is Silvestrov’s song cycles and piano works, his kitsch, that I return to again and again. His “Silent Songs” were the first in this series of simple works that have that Schubertian ability to distort time. You find yourself holding your breath. Even his most direct melodies are fleeting, as if glimpsed from a train window. British critic Malcolm MacDonald wrote that Silvestrov writes not the lament itself “but the lingering memory of it.”

To sample this music, I suggest three discs.

First, the song disc “Stufen” with pianist Alexei Lubimov and mezzo Jana Ivanilova, on the hard to find Megadisc label that can be streamed for pay at Amazon or free at Spotify, settings of poetry from the likes of Keats and Pushkin. The echoing sonic ambience adds a shimmering haze to the nostalgia, a disc so intimate the listener feels almost an eavesdropper, as can hear here on “Elegy.”

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

In recent years, Silvestrov has expanded his sonic scale with choral compositions rooted in Orthodox tradition and advancing the composer’s gift for achingly evanescent melodic constructs. ECM has released a pair of recordings with Mykola Hobdych leading the Kiev Chamber Choir in these a cappella gems, the first of which BBC critic Michael Quinn called simply “ravishing.” Sample the Ave Maria, you’ll agree.

Silvestrov’s music could be grouped with Pärt and Górecki, but that misrepresents his unique approach to melody. He is far less given to minimalist sequencing than these other Eastern mystics. Silvestrov’s music is perhaps anachronistic, but the question isn’t, why do we need more traditionally beautiful tonal music? The question should be, why would you turn away from this?

– Milton Moore

December 3, 2018

The Perverse Imagination of Edward Carey

A FEW weeks ago I got a historical novel, written for adults, called Little, based on the life of Madame Tussaud. I soon learned that my 12-year-old son had beaten me to this author’s work: He’d already read Heap House, the first novel in the outlandish, fantasy-based The Iremonger Trilogy, aimed at precocious kids. I was lucky enough to speak to the writer, Edward Carey, about how he kept it all straight, and how slight the differences between categories are.

Part of what I most enjoyed about our conversation was discussing fairy tales: Carey teaches a class on the subject at the University of Texas, and spoke quite eloquently about the continued relevance of the form. His description of our current president as a figure from a folktale — a surly, oafish, overgrown king who has so frustrated his intimates and advisors that nobody tells him the truth anymore — was especially dead-on, I think.

Space limitations kept me from getting into how obsessive and accomplished an artist Carey is. He illustrates all his books himself, and in the years he was trying and failing to write a novel in Tussaud’s voice, he was somehow able to create, and display, visual images of her.

Anyway, the story, from the Los Angeles Times, is here.

November 29, 2018

The Art of Judy Dater

RECENTLY I got to spend a little time with the Los Angeles-born, Bay Area-dwelling photographer Judy Dater, whose work goes back to the 1960s. Dater’s been experiencing a bit of a career revival lately, with a recent show at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, which has now come to Loyola Marymount University’s art gallery, and a beautiful, career-spanning book of her work, Only Human.

Dater is a case of an artist who’s remained close to a handful of abiding concerns, and a visual style she hit on relatively early, who has managed not to repeat herself. (Her relationship to feminism, for instance, is sort of fascinating.)

Here is my story on the life and work of Judy Dater, for the LMU magazine.

November 15, 2018

The Music of Stanley Kubrick

A FEW months ago I went to see a restored 70 mm print of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and film I had not seen (I realized) in decades. A number of things struck me, among them how beautifully and in some ways unconventionally Kubrick used the music in the film. (Of course, the the slow, ruminative, color-soaked grandeur of the movie was also very hard to miss.)

This is of course not the only time Kubrick has done something smart, imaginative, or shocking wit the music in his films. He’s a fascinating character: I know as many people from the literary world or from rock bands who revere Kubrick as I do among the cinephile crowd.

Over Thanksgiving, the LA Philharmonic will present the music from five of Kubrick’s movies — from 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut — with scenes projected above the orchestra. Here’s my piece for Los Angeles magazine.

(I get a slight kick out of the name of the Phil’s project — “Stanley Kubrick’s Sound Odyssey”; the hometown record store where I bought my first albums was called Sound Odyssey.)

November 13, 2018

Arts Funding: The US vs the World

NOT long ago I wrote a story about the arts in LA since the Great Recession. I spoke to so many people, some at length, that most of my reporting ended up lost in my notebook. One of the more intriguing conversations I had was with David Sefton, the former head of UCLA Live, now running arts festivals in Australia. I asked Sefton — whose early years involved booking and presenting in Liverpool and London’s South Bank Centre — to compare the funding models in the US, UK, and Australia. Here’s his response; I’ve left the British spelling intact.

When you talk about “Funding Models” its important to realise that the States effectively doesn’t have one. Referring to what happens in the US as a Funding Model is like calling an earthquake a Lifestyle Choice. Its survival of the fittest and absolute dependence on the kindness of strangers.

There are some upsides to philanthropy – you really do get to know your audience because your life literally depends on them. And I definitely got to meet some lovely people who effectively paid my wages. But its very hard work. And of course the art forms it favours are the ones favoured by those with the cash – which means the bias is always going to be towards the traditional – or in the case of Visual Arts, the potentially profitable. And as a charity you are lined-up with all the other charities, cap in hand – which is great when the economy is going well, but when everything falls apart the arts are always the first thing to go.

There are some upsides to philanthropy – you really do get to know your audience because your life literally depends on them. And I definitely got to meet some lovely people who effectively paid my wages. But its very hard work. And of course the art forms it favours are the ones favoured by those with the cash – which means the bias is always going to be towards the traditional – or in the case of Visual Arts, the potentially profitable. And as a charity you are lined-up with all the other charities, cap in hand – which is great when the economy is going well, but when everything falls apart the arts are always the first thing to go.

That’s not to say the other models aren’t without their challenges. The UK arts is in a terrible state at the moment as the lifeline of subsidy gets reduced or cut entirely.

In fact, having worked across them all I’d have to say that the only conclusion is its a mixed economy that works best – its just common sense: a single source of funding is always going to be perilous no matter what that source is. More and more I’m coming to the realisation that the only way the arts will survive is if it can not only sell tickets and cultivate supporters but also keep its bar sales and parking income – it sounds mundane but survival in the future is going to depend on the range of places you can find the money.

November 2, 2018

The Arts in Los Angeles, 10 Years After

SOME of you may know me as the author of a reasonably gloomy book on the arts, the recession, digital technology, and our fraught cultural future. When I was approached recently by the Los Angeles Times to take a look at how cultural institutions, large and small, and individual artists had experienced the 2008 crash, the belated recovery, the ensuing housing crisis, and the rest, I could not really turn it down, party because I was genuinely curious to look with more depth than I had in several years.

What I found is HERE. In numerous ways, Los Angeles has weathered this better than a lot of other US cities. But as you’ll see, the picture is certainly complex. I worked harder on just about anything I’ve done over the last two years — not just on the reporting and research, but getting the balance and proportion right in the writing.

What I found is HERE. In numerous ways, Los Angeles has weathered this better than a lot of other US cities. But as you’ll see, the picture is certainly complex. I worked harder on just about anything I’ve done over the last two years — not just on the reporting and research, but getting the balance and proportion right in the writing.

The trick here is that even if we’re all Angelenos, everyone’s story is somehow different.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers