Elizabeth Knox's Blog

February 14, 2021

Why I wrote The Absolute Book

Why I wrote The Absolute Book

The Absolute Book owes its existence to my sense of coming back to life as time and events intervened between me and some bad years. Years during which my mother was dying of Motor Neuron Disease (ALS) and my brother-in-law was killed in much the same way the novel’s protagonist’s sister. That feeling—of sudden freedom from responsibility, but with indelible memories of the strictures of responsibility—seemed to want me to do something with it. The sense of a freedom of movement that comes with being finally able to leave the worst troubles behind. Or the troubles themselves leave. You keep a vigil, then the one you’re watching over is gone and you get to walk away tired rather than run away scared.

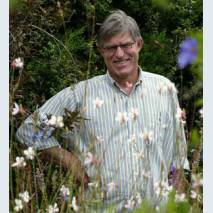

Me and my husband Fergus did a lot of traveling in the ‘afterwards’. I wanted to capture something of that; all our walking through the world. And how, the further we walked, the bigger the world became.

The Absolute Book began directly when I started musing on the kinds of stories I love. Particularly those I’d loved for a very long time.

I was sixteen when I read Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. I can still remember my thump of excitement at the movement from chapter one, ‘Never Talk to Strangers’, to chapter two, ‘Pontius Pilate’. In chapter one a couple of members of the Writers Union are having a conversation by the Patriarch Ponds in Moscow on a hot day sometime in the late 1920s. They are interrupted by a foreign gentleman; a professor of some sort. After a time the men’s conversation turns to theological matters, and the foreigner begins to tell a story. The first lines of his story are the final lines of chapter one, and the first of chapter two:

‘Early in the morning of the spring month of Nisan the Procurator of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, in a white cloak lined with blood-red, emerged with his shuffling cavalryman’s walk into the arcade connecting the two wings of the palace of Herod the Great.’

Chapter two almost entirely concerns the examination of a troublesome and deeply touching rebel by the migraine-stricken Procurator. The whole of the novel, with its witches and night flights, its communist officials and badly behaved poets, its venal Muscovites, vexed theater impresarios, depressed novelists and talking cats was enormously influential for me. It isn’t just the quality of The Master and Margarita’s bookishness that I love (there’s a suppressed and very nearly burned novel manuscript at the center of the story), it is also its humor, its seriousness, artistic and intellectual; its and fearlessness about being farcical, or being grand; its sense of wonder and enchantment; its deep and real feelings. All of those things managing to sit singing with one another in a single book gave me a sense of what it was possible to do. I never forgot the way that book first made me feel. So, when I started to think what to do with the great feeling of freedom that came upon me after having being deeply sad and deathly tired, I thought about The Master and Margarita.

My next thought was that if I was going to try to write something tonally varied, it would be a very good idea if it had a number of fantasy tropes that were familiar, and would help shape the story. I liked and had been musing about the sort of book in which a group of people spend the novel looking for something. A thing. An object. Some of those books were what you might call arcane thrillers. Books like The Da Vinci Code or Shadow of the Wind. Books with a scholarly hero, and peopled by groups with competing or collaborative interests related to the thing they’re trying to find. Books full of reasons for strangers to talk to one another. Reasons for strange bedfellows.

Why Libraries?

Since I was writing a book about what to keep, and how sharing is keeping, I thought ‘libraries express that’. I had things I wanted to say about the worth of libraries. Libraries have always been a refuge to me—and a library and librarian pretty much saved my father’s life when he was a 13 year old removed from his home and sent to work on a farm—and sleep in a tin shack with a dirt floor— in the Wairarapa in the early 1940s. I decided my novel must have a protagonist who has written a book about library fires, a book that is doing well and drawn all kinds of attention. (I’ve always loved books where the main characters have work, where work shapes their lives and the story.) I thought about libraries as treasure houses, as refuges, and centers of community. As hubs—places to come in to and go out from. (There’s a lot of coming in and going out in the novel). But The Absolute Book is also a novel where a group of people central to the story—the sidhe—don’t even have libraries. They don’t have books. They themselves are their only memory-keepers.

As soon as I started writing my writer protagonist, Taryn Cornick, what happened was that all the other things that had been sitting around my mind came out again. So I gave Taryn a sister who was deliberately killed by a man with a motor vehicle, like my husband’s brother. Questions of punishment and revenge and forgiveness came into the book with that. Also, it quickly became obvious to me that Taryn hasn’t got over what had happened to her sister – though it is years later. Mostly she hasn’t because she took revenge, and that alienated her from herself. At the start of the novel Taryn exists in a constant state of doubt about the safety and goodness of the world. Her professional life is sorted, but her personal life is a leafless tree.

So, I was writing a book about being haunted and being unable to forget, and being culpable and needing to remember. Also, very much, about visibility and concealment—lost books, and hidden people, and truths too big or strange to see.

The novel opens with a woman with a grief, a revenge, a crime, a book.

Taryn, her grief at her sister’s death, the crime she committed, and her personal association with an object people are looking for—that’s all the centrifugal force in the novel. Taryn pulls everything towards her. Of course, some of the things she pulls towards her have their own gravities, and are whole other worlds, with green roads to walk.

And, as sure as the foreign gentleman in chapter one of The Master and Margarita is the devil, The Absolute Book was always going to be a full-throttle fantasy. The novel’s other principle character, Shift, a person who calls everyone people—everyone from chickens to demons—has, like the book itself, an egalitarian, even-handed approach to the everyday and the mythical. Shift is the friend Taryn makes. He’s something between Dante’s poet guide and the magical animal that accompanies the hero on a quest.

I wanted to write a novel that seemed to be opening out into an epic as we understand fantasy epics but, like a good mystery, would keep doubling back and deepening the discoveries and the experiences of its characters.

The Sidhe

The Absolute Book isn’t a book about books with fairies in it; the utterly unbookish sidhe are equal to the books of the book. I wanted to write about a beautiful society founded on theft. Not beautiful as in wealth, private property, astonishing tools. The sidhe are nomadic, communal, and live along broad paths of food forests, gardens that run through wildernesses. They pay for what they have in human souls, though they love and nurture the humans concerned for a long time in happiness and plenty. The reader might think about the expedience and cruelty of late stage capitalism, or our relationship with farm and companion animals. But this isn’t an allegory. The sidhe aren’t something in costume, they are people different than all the people we know, who might also be understood as the people we know.

The Absolute Book is an arcane thriller, a fantasy, an adventure story, and a recovery narrative. Because it started with my desire to share the feeling of coming back to life Taryn does come back to life, she figures out how to live, what to do with herself, how to love those she loves.

I wanted the novel to be transporting and moving. For the person in the novel who has made a terrible wrong-headed error to face up to things, make amends, and get better. And for the almost paradisaical society – but one founded on treachery – to change its ways and begin to move in the right direction. For good things to happen because people learn to see that the interests of very different others are equal to their own.

The Ending

The ending is a happy one, though it allows some uneasiness too. It’s wish-fulfillment, aimed to make readers feel the wish because, though there may be no gods, frost-giants and fairies, we do have governments, and governments have it in their power to save the world and look after their citizens during the process of saving.

March 1, 2020

Useless Grasses: On Imagination

This was the opening address of the New Zealand Festival’s Writers’ Week. I was honoured and privileged to be asked to open Writers’ Week.

It’s Saturday not Sunday morning, but let us imagine we’re a congregation. Each of us owes the other, we keep ourselves in check, we look to one another when we’re low, and want not to be shamed in one another’s eyes. We sit together listening, often looking up and out, past the ancestral memorials, to the view beyond the window of slow, heavy clouds on a day when rain is gathering and the wind is low. Some of us are simply watching the weather, some looking for a hidden heaven, some for—or at—God, some at planetary time. Several of those things might be imaginary, but we have to imagine all of them—even the weather now.

Last November in Golden Bay my husband Fergus, sister Sara, and I, went for walk a way we hadn’t taken before, which is unusual since we’re always going to Golden Bay. We saw a South Island black piwakawaka. The little bird wasn’t making its usual sound of someone vigorously washing a little window. The day was hot, and the birds were all subdued, perhaps from a first fine distillation of Australian bushfire smoke staining the sky. The piwakawaka was silent, smaller than the North Island bird, a flitting scrap of shadow. Its tail was crenelated because it had been moulting and its feathers hadn’t filled out again. It was recognisable; and quite different. We hadn’t seen one before.

Novelty in the natural world is something people tend to notice more as they get older, because often they’re seeing things again and the delight is in thinking, “There it is. Still there.” A reaffirmation almost more marvellous than anything seen for the first time.

A month after that walk, and that bird, when the sky in Wellington was orange with smoke—another new thing—I remembered having thought about that: the world’s constant, quiet reaffirmation of itself. And it suddenly seemed far less solidly promised than it had before.

So, it’s a Saturday, but imagine we’re part of a congregation praying for clemency, and our prayer goes, “We know now. We know now.” With a light refrain of, “If only we’d known.”

What was I thinking when, fifteen years ago, I was having a self-congratulatory conversation with someone overseas about the newest find of natural gas in the sea off Taranaki? This, I said happily, will really help with New Zealand’s ongoing energy needs.

I’d failed to make connections, and it was a failure of imagination. The first thing we have to imagine is that there are things we’re missing, that we don’t know, that elude us. We have to imagine the scale of our failures. What we can’t see at all, or can’t see straight. We’re so busy beholding the mote in our brother’s eye that we can’t considered the beam in own own.

Once, in an antique shop, I found a late nineteenth-century display box of botanical samples made for identifying plants. The case contained a labelled collection of “useless grasses”. The grasses that, if you found them in your paddock, you’d pull them out before they seeded and gained a foothold on good pasture. I often think of that sampler of useless grasses. Of the whole idea of uselessness in plants, and all the things that, over time, human beings decide they no longer need, or can’t imagine needing later. I think about it when I worry about the future of libraries. And I think about it when, once again, I come up against the idea that non-realist fiction is childish because it somehow doesn’t represent the world as it is. That idea, that there’s a world as it is—a given, agreed upon, non-negotiable world. As it is.

But what if that world were to disappear? What if it is disappearing? Hastening to change—to turn it spiny, scaled and un-scalable back on us, until it isn’t a world we can climb on and fly away to another world, it won’t let us, it won’t forgive how we failed to imagine it.

I’m going to tell you a story about an ordinary use of childhood imagination, by children—which is also an account of the first time I was aware that I, and another child, were using our troubles to make a fire, a forge, and a story. A story that was believable because its foundational energy was unreasonable trouble and unreasoning rage.

It was in the summer, for me, between primary and high school. A summer we kids spent swimming out to launches moored in Brown’s Bay Paremata, and stretching their protective canvas covers by lying in them, sunbathing, as if they were hammocks. Sometimes Barnes the harbourmaster would row out to chase us off, or sometimes he’d just stand on the beach and scold us through a bullhorn until we slipped into the water like unwelcome seals and swam out to some more distant boat.

Other times we’d walk up to the pine forest on the crest of the hill between the Brown’s Bay houses and the then new subdivision of Whitby. The pines were old and tall, the space between them a vast russet-floored chamber—scented and silent. An enchanting place. But out of magpie nesting season the pushy world wasn’t there at all. There was nothing for us kids to pit ourselves against, no territorial birds or incensed harbourmasters.

We were usually the same group—two Murphys and two Knoxes. Wendy Murphy was near to me in age, but would still be at Paremata School in the new year. I was twelve at the start of my third form. Robbie, Wendy’s brother, was a year older than my sister Sara. And then there was Sara. We Murphy and Knox kids were the children of intellectuals—or, arguably, demoralised and neglectful parents. We were left to drift, often in and out of danger.

If we hadn’t been in the forest for a while we would always walk straight through it to check its shrinking boundary on the Whitby side. Which is how we found ourselves on a day that seemed particularly empty of any entertaining chafing against the world. A soupy grey day with gusty wind of the sort we have more often now. We were sitting in the treeline on the slope above the sweep of a street of empty sections, half built houses, and a few new houses. In the backyard of the house below us were four children. All freckled and fair haired, the youngest a pre-schooler with a wide gait who was stumping from sibling to sibling to stand at the elbow of each watching what they were up to, and waiting to be included. The other girls, maybe seven and ten, were shredding leftover pink batts and attempting—it appeared—to dissolve them in a plastic paddling pool, as if the fibreglass was candy floss. The oldest child was riding his bike in tight circles on the bare clay patch. It was he who looked up at the treeline.

“He seen us,” I said, and grabbed Wendy’s arm and pulled her back into the darkness under the pines.

“We’re not trespassing, and they’re just kids.” Wendy was practical—she didn’t like to play pretend, but she had a dark and deep sense of humour that meant, when encouraged, she might just walk off with any moment that presented itself as portable. And I could always bring it out in her. I said to her, all drama and urgency, “But we have to trust someone!”

The words came from television—you’d walk into the living room and there be some program only parents and older sister watched, and someone on the screen would be saying something television-ordinary, but it would still make you wonder what the problem was. What was to be done about it.

I looked behind me. Robbie was sulking about something and kicking a furrow through the smooth pine needles, while Sara made a pile of small dead branches, as it she meant to build a fire. This provided me with a cue. I told Wendy she must remember we were only allowed out for as long as it took us to gather firewood.

Wendy gave me an assessing look.

“They’ll be back before we know it,” I said, “We’ll be locked up again. We have to trust someone.”

Wendy turned and told Robbie to go further into the trees, but to stop where we could still see him. “You’re keeping a lookout.”

Robbie wanted to know why, and I told him that someone had taken us prisoner and we were only out in order to collect firewood. Wendy and I were going to try to alert the kids in that house down there to the situation; meanwhile he should keep a lookout.

Robbie came over to eye up the kids. The boy and one sister were obligingly climbing the hill. We hadn’t even had to make urgent signals. For good measure, we made some urgent signals.

Robbie dashed off to his post. I told Sara she was gathering firewood for our kidnappers and, after I cleared up her confusion about how I knew someone was coming to kidnap us and, if so, why was I just standing there, she went on with what she been doing, while somehow making her solid little self in her striped T-shirt and stretchy fawn shorts look peaky and fearful.

Wendy and I kept signalling to the children while backing away into the forest.

Wendy looked the part of a prisoner. She was tipping over from a sleek childhood into a phenomenally oily adolescence. She couldn’t keep her hair clean. And I looked, as my mother liked to say, as though I’d been dragged through a bramble backwards. We acted the part. The kids came up to us and we put our fingers to our lips and drew back, and further back, and they were obliged to follow us as far as Sara’s woodpile.

The story started as a two-hander, Wendy and I glancing at each other now and then. We told them how we had stumbled upon something—consulting between us with looks—some days ago, it was hard to say how many days because we were being kept underground. The men—there were a lot of them—worked in shifts so everyone ate when they got up and when they went to bed, meaning two meals every twenty-four hours at changes of shift. We were fed only every second meal. It was difficult to keep track of time without meal times and daylight, we said.

Sara chimed in to say that she was hungry and it would be great if they could fetch us some food.

I watched the boy’s eyes narrow and quickly said to Sara, “No, you’re just going to have to go hungry. We only want to get a message to our parents.”

“Not to the police?” said the boy. It was the obvious question.

“Only our parents.” Wendy was firm, and grave. “We’ll ask them to reply. We need to know what we should do.”

I thought this was hardly the best excuse for not calling the police, but that I didn’t have a better one. And Wendy was selling it really well. A wish—that you could take a situation of danger to a parent to get a hearing and advice—was pushing itself to the front of our story and I could feel the energy of it, without yet having been directly disappointed by parents myself. It was another year before I knew what Wendy knew, how an everyday expectation—that a parent would do what they should when applied to for help—could turn from an everyday expectation into a lifelong wish. For now, what I was able to think was that it was good for our story, that strange force in Wendy’s feeble excuse for a plot. Force coming from somewhere I didn’t understand. But I did understand that it was a great move to give the kids something to do—to bring us writing paper and pencil, rather than the snack Sara was angling for. Because there was no further business in the snack once it was eaten. We could direct the kids to a letterbox—ours would be best—I’d be able to haunt ours, at least till school started. And if I wrote the letter, then Wendy could write the answer ostensibly from our parents, and we could come back here, to the Whitby side of the forest, so the kids could deliver it.

We explained our plan. And, “Please,” said Wendy.

“Please,” Sara said, then added, “They’ve threatened to beat us.”

“Or at least we think they have,” I said. “They have accents that make them hard to understand.”

“What kind of accents?” asked the boy, still doing his due diligence.

“They only speak English when they’re talking to us,” I said. “We can’t understand what they’re saying when they’re talking among themselves. We don’t know what they’re up to. We don’t know why they here.”

Wendy said that the one who had the best English and spoke to us most often sounded more Czech than Russian. Some years before she and her family had spent nearly a year in Germany, and had taken trips to several other countries. “He’s the one who threatened us,” Wendy said. “He seems to be a bit on the outer with the others.”

“Russia invaded Czechoslovakia,” I said. “He’s probably further down the pecking order. We’re the only ones he can take out his feelings on.”

I don’t know how much geopolitical savvy the boy had, but he’d started nodding.

Robbie drifted back.

“You’re supposed to be keeping watch,” I hissed, and made a gesture at Sara to take his place. Sara scuttled off, pressed her back to the pine trunk and peered around it.

Robbie wanted to know what was going on. Wendy explained the situation to him—how these kids were going to help us get in touch with our parents.

Robbie asked their names and offered his, which wasn’t a thing we’d thought to do. I remember they were mcsomethings—McCartneys, McAndrews.

“Why don’t you just run off?” The boy’s sister asked. “Like now?”

“When they send us out they always keep someone back,” Wendy said. “Our little sister.” She pointed to herself and Robbie. She and Robbie did have a little sister—and a big one, who had run away from home the year before, and disappeared.

“Our big sister,” I said and indicated myself and Sara. So, we were in a thriller with a Russian underground base and an abduction, but hadn’t, for economy of invention, decided to be one family.

“Can you just start by getting us a paper and pencil?” I said.

The girl darted off to the edge of the forest and bellowed at the next girl to get writing stuff and bring it up here.

I wrote the letter. We didn’t have to stretch out the task and our invention, because the kids’ mother appeared below and went off her nut about how they’d left the toddler unattended with the paddling pool.

I pressed my unfinished letter into the boy’s hand and gave him my address. I told him we’d be back for the answer and to watch for us.

They loped off downhill. For another few minutes we made a precautionary show of breaking branches off a fallen pine bough—but the kids had all gone indoors. We realised we’d have to get rid of the piled wood and spent another half an hour wandering in separate directions, and scattering it, before heading home, us Knoxes to start staring at the letterbox.

The McSomething’s did deliver. And they collected Wendy’s concerned fatherly reply, a letter as advised not too full of questions or threats in case it “fell into the wrong hands”. We returned to lurk at the Whitby edge of the forest. We remembered to wear what we’d been wearing that first day, but made our clothes a bit grubby. And Wendy and I got out our coloured pencils and pastels, and I borrowed my older sister Mary’s expensive set of acrylic paints, and we made bruises of pastel and pencil, and scabs from Mary’s acrylics, reddening the surrounding skin with Wendy’s mum’s blusher. The blusher was a risk since it was the only component of our fake injuries that smelled fake. We made Sara a little ghostly with talcum powder and, on our way up the hill, she found a right-sized branch and practised using it as a crutch.

We had to wait till we were spotted, then the kids all came up the hill, the toddler piggyback. They handed us the letter. Wendy opened it. I turned away to wipe my eyes. Sara limped closer, but not too close, because her make-up only really worked in the gloom. We spared some attention from our parents’ precious communication to explain that the men had made good on their threats.

“We didn’t even do anything to provoke them,” Robbie said. Then to Sara, concerned, “Has your ear stopped bleeding?”

I think we met those kids four times altogether. We were flighty and hypervigilant and wouldn’t let them get too near—not wanting to risk them seeing how our plastic paint scabs had come loose and were only attached to our skin by the hairs on our arms. When they were sceptical, which to their credit was often, they’d question us. But the questions were never the ones I expected and dreaded because I couldn’t answer them—like what would an underground base do with firewood anyway? They asked the human questions—what was being done by whom, and for what reason, and how we felt about it. And they carried our messages. Our story made use of their bodies and their time. And eventually they did bring the pale and loitering Sara some biscuits.

This game was a major preoccupation the summer after my last year at primary school. Of the games of my childhood it wasn’t the most intense, or prolonged, or loved—but it was the most extravagant and stagey and outlandish. I should say here—for those who might have read it—that Wendy is Grace in my autobiographical novella Tawa. Tawa tells a dark and terrible story—but the real story is darker and more terrible still.

Wendy and I drove that game, with some star turns from Sara, and Robbie’s presence—a boy with the girls—making it possible for the oldest McSomething to imagine it was okay to talk to us. The conceit of the game worked because of our collective sense of fun—Wendy, Sara, Robbie and I were enjoying ourselves, and so were the other kids who, after all, had just moved in and knew no one and there we were on their doorstep, and all it cost them was some packets of biscuits and a few forays into the old part of their new neighbourhood.

So—a sense of fun on everyone’s part. But it was something else as well for Wendy and me—twelve years old and already burned black at our edges. We were learning how to put the energy of ourselves into invented things, silly things, like letters to parents saying “Help, we’ve been spirited away and shut in the dark”, and letters from parents asking “Tell us what we can do to help you”.

There is a tedious common understanding that works of pure imagination might be said not to be silly only because they take a thing we all agree is real and serious and make of it a differently costumed likeness. All serious works of fantasy and science fiction are really about…and here you can fill in some big-ticket item, some gnawing trouble of society. The imaginative representations are a code, where everything matches up one-to-one.

In this view all fantasies must be allegories—and as allegories at least have dignity of dress and deportment. Because, if they aren’t allegories, and it isn’t a code, where do they get their meaning from?

I think you can sense my exasperation with this mindset, which doesn’t matter, except when it does, like how confident and eager we are to praise Margaret Mahy because she was a beloved writer, rather than because she was a great one. A woman, an author of children’s books, a fantasy writer, a great writer in a culture where, when I was a kid, parents would say, “Are you just going to sit there all day reading that book? Why don’t you go outside and do something?” A culture that has a tendency to think of imagination as something that’s nice to have, especially for young and developing minds, but is something that has its practical limits.

Its practical limits might be the death of us all.

This summer, like that one long ago when, in a rage of invention, I started looking around for somewhere safe to put myself, I’ve been, more consciously, thinking about saving myself which—at the age of sixty and deeply embedded in my life—means saving other people.

My sister Sara, of the piled firewood, lives in Medlow Bath, in the Blue Mountains, New South Wales. Sara is in the neighbourhood support arm of the Rural Volunteer Fire Service, which means she has a locked trailer of firefighting equipment parked at her gate, so that she and her neighbours can fight embers and take responsibility for the late evacuation of animals and people into their “place of last resort”, a brick-walled, asbestos-roofed house a few doors down from Sara.

Twice she’s left Medlow with her cats and chicken to shelter with friends in Sydney, though she hates to leave if anyone else in her community is staying. She’s been awake all night in forty-degree heat unable to open the windows, because the air isn’t breathable. And she’s had tearful conversations with people in her local shops who don’t know how they will manage to keep their livelihoods since the tourists and the holidaymakers are staying away. “I’m not complaining,” Sara says. “It’s the same for everyone.” She speaks quietly, in a voice drained of energy. Her emotions cauterised, which means the burning of the flesh to stop bleeding. Because how are you supposed to feel when the wind changes and the smoke clears and the trees of your garden are full of birds because they’re the birds who managed to fly away from the fire and are now living in a strip of green along the great Western Highway? Sara has gone beyond dread, into exhausted fatalism. “I have cats, not kids,” she says. “I can only imagine how it is for people with kids.” She tells me that all the New Zealanders are talking about coming home. And I say, “Come home.”

One evening during all this Fergus asks me have I seen that terrible video of the cockatoos in the heat wave. The ones who can’t fly anymore and have fallen to the ground. And the ones who can still fly and keep trying to feed them.

“I’m not going to watch that,” I say. And then I can’t stop thinking about it—thinking that, before too long, we’re going to be the cockatoos, those of us who can still fly trying to feed those of us who have fallen.

The summer for me between primary and secondary ended, and we all went back to school, and at Paremata, on the first playtime, Sara spotted the three school-age McSomething’s clustered in the playground. And they saw her. She rushed up to them waving her arms. “We escaped!” she said. “But we’re not allowed to say anything about it. The police are watching that base to see what those people do and we have to keep it a secret. We might never know what happens!”

“They believed me,” she insists when we’re trying to put our memories together. “I’m sure they did. I’m not ashamed of it. We gave them an adventure.”

Because I write fantasy, which is sometimes equated with not putting away childish things, I often feel a need to make an argument for fiction that is full of stuff that is true, while yes less solidly dependent on, I won’t say material facts, because material facts are a whole other thing, or a vast class of things from viruses to black holes. Let’s say the facts of matters, rather than matter. Matters like the political realities that we are always to consider, economic realities that teach us that many things of value have fluctuating values and we have to accept that no matter how necessary those things might be to our well-being the fluctuations have made them, as they say, simply out of our reach, like a house, or a life-saving drug. But what’s simple about that? What’s simple about suffering? The worlds of fiction faithful to this world behave according to the material realities of markets, money, media and the politics of all that, how the people in those worlds see themselves, and behave according to what they see on a sliding scale from knowing complicity to knowing revolt; a sliding scale from “this is how things work” to “this isn’t working.” And that’s all great and fascinating.

But fiction less dependent on the facts of matters might be more able to ask: What if this world as it is—as it has been since the Industrial Revolution—is just now?” What if this world was very different? What if the powerful lost their platforms, but not their lives or dignity. What if the last can be first? Or we can make a melange of firsts, like animals at a waterhole, heads down, only our ears and tongues moving in the temporary accord of a common thirst.

Imagine that. Imagine standing still for a generation. Imagine fixing things and feeding ourselves. Imagine taking care of everything and everybody, and our governments behaving like kind parents who really do know better, rather than corporations mindful of their shareholders. We’ve been encouraged to be jealous and punitive, like the children of the too large family whose parents’ regard is the only regard worth having. Or the children of a small family with a parent parsimonious with love whose regard the children feel they have to constantly fight for. But look around you. Who is looking at you? Perhaps the thrush on the bank within arm’s reach of where you’re walking who looks at you but doesn’t stop tossing the leaf mulch about delving for insects. Even if like me you stop and speak to the thrush, one of those birds—the birds of Wellington—most of them won’t fly away. You can almost see them thinking that that would be an overreaction. Why do the birds of Wellington these days not startle like the birds of my childhood and youth? I think they don’t count us as dangerous in the same way anymore. They don’t know how they are valued—valued and enjoyed—but our changed attitude to them has changed their attitude to us. I’m pretty old now, so that’s generations of birds. If we can change our mutual relationship to beings to whom we can’t offer any explanations, why can’t we do better with ourselves?

I keep going back to animals. I do because, while we so-called ‘writers of imagination’ were using myths and monsters to think how we might be different, they—animals—were always there; there so that we might look at them and imagine how we might be different or, whenever they come to us for help, how little difference there is between us and them.

Thomas Carlyle wrote, “Not our logical faculty but our imaginative one is king over us.”*

So, sisters and brothers, imagine the last being first, and the lion lying down with the lamb. Or us lying down as lions and lambs in some ceremony of the future commemorating lions. A ceremony with stories about lions, to which our great-grandchildren will listen and then imagine lions. There was the life, and after that, the resurrection, which is the life imagined.

*

I used another Carlyle quote in my speech, but misremembered it, which is funny, since it’s the epigraph of my next book!

October 19, 2019

My Prime Minister’s Award Speech

For about ten years between when their daughters left home and Dad lost his licence and confidence after a couple of accidents while reversing in the supermarket car park, he and Mum would go on long late summer, exploratory driving holidays. Dad with his two Canons, photographing landscape – the sun-blistered jarrah waterwheel at Mount White Station where Mum’s father had spent the first twenty-one years of his life; or terns on the glistening sand of the estuary at Pakawau.

Mum would collect stones. Not the geologists’ pink quartz, or olivines, or Separation Point granite, but stones for which she had her own names – honeycomb or ice cream. One year in Jackson’s Bay Mum left her whole holiday’s stash on the porch of their motel – and it vanished overnight.

There had been a friendly weka that evening eyeing up their plates of boxed chicken chow mien. The weka was Mum’s prime suspect. “Blow me down, my stones were all gone,” Mum wrote me on a postcard. “Bother him, the jolly nuisance” and “I’m miffed.”

When I’m writing. I often think of Mum’s words – the way her time sits inside them, as time sits inside all words. And I think of her weka.

There are things I summon to mind whenever I sit down to write something difficult – either painful and knotty, or some scene on which a whole novel depends – and there are a lot of those. Some days I’m loading a revolver, thumbing the brass cases of bullets into the chamber of a gun. More often I’m Mum’s thieving weka, patiently and illicitly moving valuables from one place to another, porch to page in my case. But even though I’m alone and any writing room is the dark depths of night, unlike the weka I’m shifting things from hidden to visible.

The writing life is like that – it isn’t the movie montage of a writer peering at a screen and biting their thumbnail, a wastepaper basket overflowing with balled up pages beside them. It isn’t the other gigs, though they’re part of it – being the teacher who motivates and illuminates, or the speaker who moves people with sermons or showmanship. The writing life is quiet and wild, and covert, and I’m very grateful to all the people who, over the years, have enabled me. For the confidence and goodwill of Creative New Zealand and the Arts Foundation of New Zealand; for the ongoing energy of the International Institute of Modern Letters, of bookshops and libraries and writers festivals; for the kind support of friends; for the valiant support of publishers, particularly Victoria University Press; and for the brave and sustained support of my family, my sister Sara, my son Jack, and always, always Fergus. And, in the end, my readers who, whenever they climb into bed and crack the spine of any of my books are the same as me – quiet and wild and private. Their attention and interest is the life of books, and the afterlife of writers.

Elizabeth Knox and PM Jacinda Ardern

September 21, 2018

Continuing

This essay appears in The Fuse Box: Essays on Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters

This essay appears in The Fuse Box: Essays on Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters

At some point in every writer’s life they’ll find themselves facing the question, ‘Why write?’ Because it can be a lonely slog, and you have to like it. Because it’s always been difficult to make any money, and it’s even more difficult now.

Young writers, those with fire in their bellies, never think, ‘Why write?’ What they think, and should, is, ‘Why not?’ I used to think, ‘Why not?’ Mostly in response to the surprisingly many people confidently prepared to ask, ‘Who are you to think you can do this?’ I got into the healthy, bloody-minded habit of asking, ‘Why not me?’ And the thing is, that however difficult the lonely slog, it becomes normal. I’m aware that mine isn’t a life a lot of writers have. Lots of them have jobs teaching writing. Or have jobs in order to supplement their writing. I’ve been lucky. Also I’ve been sequestered. And that has been for the most part wonderful. But it isn’t easy, and eventually that defiant but joyful, ‘Why not?’ turns into, ‘Why? Why write?’

When I was younger I used to write things down in my journal as if doing so would make some difference. I had an idea of myself as a witness, and that there was something intrinsically useful in my going about the world noticing things. Processing them, and making a record.

When I first read King Lear in the seventh form, I was struck by Lear’s proposal to Cordelia that they be like God’s spies. He is so happy to have found the daughter who loves him. So happy to be with her, that the prospect of being tossed in a jail cell with her only means with her. Sharing the same air with Cordelia is now more precious to Lear than his kingdom, than being a King and having the gift of the kingship, of power; those things he had and failed to use wisely. But this moment in the play is not just a straightforward portrait of a man reunited with his daughter, two people for whom the society of each is sufficient. It is also that, somehow, they’ve been elevated to a position where they belong more to God. If they can’t judge like God judges, they can at least witness like God. Like God and for God. At least until, ‘He who parts us shall bring a brand from heaven / And fire us hence like foxes.’

So, about writing I always thought, ‘At least there’s this being one of God’s spies.’ But when you put pen to paper, even in a journal, you have to imagine that someone might read what you’re writing. You don’t have to imagine they’ll be interested; it’s just being heard, whispering into the box of a book, closing the lid, and leaving it lying around for a very long time in the hope that someone will pick it up, open it, and hear you confiding.

I had the idea that the private act of seeing things and thinking about them was somehow useful to the good order of the universe, and that maybe my small understandings might help facilitate the tendency to things being understood. As if to be unheard, and to not have faith that you can be heard, is entropy. I believed, for a start, in writing my story, or the way I saw things, and then just stories, whatever was in my gift – which is to say, in my power to give.

But time goes on, and things happen that are ordinary, because they happen to pretty much 51 per cent of the population. You become invisible. The first several times that you order a cup of coffee in a cafe and the waitstaff forget your order it’s a great surprise. And then it happens again, and again. And you think, ‘Ah well, I’ve become invisible.’ Now, invisibility has an upside as well as a downside, but that’s a whole other story. But if that commonplace occurrence coincides with an ever shrinking pool of readers, not just for you, but for everybody; with reading being, every year, less a natural activity, then things feel a bit more acute.

*

I wasn’t a reader till I was eight. My older sister told me stories and we played games – often lying in bed in the dark – so, games made solely of words. Later I was a keen but slow reader who couldn’t write. I kept playing imaginary games, ferociously and voraciously, and holding everything in my head. Persuading people with my voice, and being persuaded by their voices.

My first relationship with story was as spoken narrative, and then as written. I fell from speaking into books. Later, with almost everyone else, I fell out of books into movies and television. And, like many others, I lost some faith in the necessary supremacy of that old wonderful thing of looking at a page, and interpreting the black marks on the white, and creating in my head the world that the words convey. But throughout my fall I retained my faith that reading books, particularly fiction, is better for us. The way a novel makes space inside us because the words have to be turned into a garden, a haunted house, a street, a wasteland; into people, and animals wild and domestic; into weather. The words only do some of the work of making the world. It’s a collaboration: the reader makes the world out of what the words have summoned in them, and that world makes room for itself inside the reader. The reader’s interior grows. And that is good for us. It doesn’t just feel good because it’s pleasurable, it also feels good because it’s exercise at the cellular level. And we do know now that there is such a thing as exercise at the cellular level. Reading fiction is health-giving; it makes you calm and orderly, and a person with fluent feelings. So, I believe in books and reading. But because I’m a pessimist I don’t believe that enough other people do, or can be made to.

My imagination and my faith can’t keep on fighting the good fight. What good is it for me to write books? Well, as my father used to say, ‘Art is inner order.’ And I think that every time I get myself into a state of grace where I stop being a believer who has faith in writing and start being a mystic who has communion with it, then delightful things are possible.

For the past eight or so years I’ve had a fascination with my own ready-to-hand. Stories whose basic world-building, or problematic premise, are derived from episodes of my imaginary game, the game I share with my younger sister, Sara, and for many years shared with a friend. That double ownership is significant. My two most recently published novels, Mortal Fire and Wake, have plots derived from episodes of the game, two each, played with my friend and with my sister. It worked like this: Sara and I were stuck for an idea we could agree on, and I reached for a plot that was tried-and-true because I’d already played it with my friend. I reused the setup. The thing about the games that became Mortal Fire and Wake was that, because I did them twice, I was able to see with greater clarity what possibilities might be produced by the same setup.

The story that became Mortal Fire, in its first iteration, was entirely peopled by adult characters. It was set in an isolated snowbound place. There was a house like the Beast’s castle, without invisible servants, but where the house cleaned and maintained itself and its chattels by mending everything at midnight, and where time, folding back on itself this way, had slowed to a crawl. All the Beast’s castle stuff ended up in the book. There was a magician deemed too powerful to be permitted freedom, who was trapped by a spell that governed both him and the house. Much of that ended up in the book. In its second iteration – the one played with Sara – the story centred much more around a juvenile magic user who, as it turned out, was the only person who could release the magician from the house. The house was situated in an isolated valley, a pastoral paradise. The magician’s jailers were his cousins, now much older than him, and they were keeping him prisoner not just because they were afraid of him, but to punish him for something that happened in a local coal mining disaster decades before. The second story is much closer to the plot of Mortal Fire. However, the novitiate was male, not female, and not a Pacific Islander, and the setting wasn’t my invented South Pacific island continent, Southland, and it wasn’t 1959.

I have no record of either of these games. Even the second one with Sara was before we began recording ourselves; before 2004, when we discovered Skype. Sara has been living in Australia since 1992, so we must have been playing while she was on holiday with me, Fergus and Jack in Golden Bay.

My experiences with Wake and Mortal Fire encouraged me to think that the stories which had excited me, when I first collaboratively made them, might be used like nets to catch the bait running in the river, tasty sustaining ideas I wanted to chew on. Though the stories are collaborative, Sara and I share them out; we get to call dibs on what we think we might use in our writing. Sara currently has a novel with an agent in the States, a fantasy with Mafiosi using demons as muscle. Very Minor Demons is substantially based on an episode of our game. I have a nearly finished young adult book called Kings of this World, a school story and speculative fiction set in Southland. It’s also based on a game, but is much further from its source. With these setups Sara and I have a record of how the whole thing played out, our voices on Skype, making up the stories together.

The trick of making use of these My Food Bag narratives is to recognise what will work in a novel as opposed to an imaginary game. Imaginary games have heat and immediacy, their worlds have to be solid enough for their characters to inhabit them, and their plots can’t have gaping holes. Their plots evolve, and don’t tend to tidy themselves as they go. We’re very good at remembering who knows what, but can be a little extravagant with psychology if it’s more productive of drama. What we can pull off in the heat of a played moment won’t necessarily work in a novel. So using a game as the basis for a novel means you have to have the judgement to go ‘this’ but not ‘that’.

Writing Kings of this World I was very grateful for the play of ideas in the original game. Ideas articulated in conversations between the characters, which were naturally spirited because Sara and I were also arguing things out – principally whether or not people are inherently good. But the plot was a dog’s breakfast, so I had to start again from the ground up. I had to ask myself, ‘What are these kids doing when they’re getting to know each other? Having Jane Austen’s Emma-like assumptions about what’s going on around them, and nurturing each other’s willingness to interfere in people’s lives?’ I had all that, so was it possible to germinate a plot out of misunderstandings, accidents and mischances. But if I did that I’d be writing a comedy, and it wasn’t enough for me to be writing a comedy when I wanted to write a thriller. A thriller with a speculative fiction plot which was also a Southland book. I had to come up with a thriller plot that wouldn’t just accommodate the comedy, but somehow rise out of it, out of gossip and conniving, and youthful high spirits. I was doing pretty well, but then I made an injurious decision that Kings needed to be a short book, and the first of two, so that I could get a sale quickly and help pay for the new garage and terrace and deck we were building.

Then, as soon as I’d declared that the book was part one of two, I realised that the material I had for a second book wasn’t going to shape itself into a novel-like entity. Shortly I’ll take Kings apart, put it back together again and finish it, as book one of one.

Anyway, I can’t help but think that apart from mistakes fostered by pressing financial concerns most of my difficulties were produced by my being like a frugal home handyman who tells himself that, since he got the demolition windows for next to nothing, the kitchen he’s trying to build must shape itself around them. And then, once his extension is well underway, the home handyman finds he has insoluble difficulties with his indoor–outdoor flow.

What happened to me is what happens to the person who starts with a given, and then has to shape the whole thing, and its needs, around something they already have. My method might have worked with Wake and Mortal Fire, but with those novels I didn’t have enchanting pre-existing voices whispering their jokes and arguments in my ear.

So – with the demolition windows problem, the having-a-record problem, it is still possible to figure out what bits of lively business you can use, and what reject. But that’s far less of a challenge than establishing the integrity of the whole picture. Your characters may be delightfully alive, but characters appear in what happens, and if you change what you must of what happens, you are inevitably going to alter the way in which those characters reveal themselves.

I have a lot of sympathy for the scriptwriters of rebooted franchises, and admiration for those who do it well. Take Marvel’s Luke Cage on Netflix. How do you make sense of the manly man in Harlem in the 21st-century, whose standard curse is ‘Sweet Christmas!’? Well – you have him trained mercilessly by his friend the barber’s adherence to a swear jar in an effort to keep the language of the street out of his establishment. It’s fascinating to witness the ingenuity of writers coping with their own famous franchise’s demolition windows.

In the end I think the major problem I had in using a given, even one with verve, and sturdy story legs, is that doing so didn’t leave any room for other things that would have turned up if I wasn’t so wrapped up in the problem of having the whole room look right with the house.

Fortunately for the plus column of the ‘Why write?’ ledger I’m having a very different experience with the adult novel I’m now near to finishing.

The Absolute Book turned up, like Dreamhunter and The Vintner’s Luck, out of the ether, and is using me to get itself written.

*

In his 1993 Listener review of my second novel Treasure Brian Boyd says: ‘Knox seems a realist by nature but a metaphysician by inclination, a magpie who can swoop on glittering detail but would prefer to be a Phoenix.’ Later he kindly and privately qualified his remark: ‘The magpie and Phoenix was an image with a semi-private echo of Isaiah Berlin on the hedgehog (who knows one big thing), and the fox (who knows many little things): Berlin compared Tolstoy to a brilliant fox who thought it was more important to be a hedgehog. Not bad company for you.’

Perhaps what I know as a writer – after many novels – is that the one big thing can only appear as a dark place in the sky, discernible because of the otherwise – the myriad visible stars.

Besides, it seems to me that, in order to write many novels it might be useful to be a bird of the Corvidae family – that is, a magpie, a crow, a jay, a rook, a jackdaw. Or a raven. Each novel has a different thing it wants, and needs to do. It’s a centrifuge that mixes. It’s a centrifuge that separates. It’s a spinning body creating its own gravity.

There’s a lot of talk about ‘finding your own fictional voice’, because so many of our ideas about writing fiction are shaped by the kindly pedagogical concerns of creative writing classes. But you don’t find your voice, you find the voice of that particular book, of a first book, a second book, a fourth, a tenth and a thirteenth. Each has its own tone it wants to take. And if I was trying to be helpful I could talk about tone. But beyond tone and voice there’s a quality that feels more telling to me when I’m trying to define the virtues of books that I’m really excited by, or when I recognise in my own work a necessity to the creation that isn’t coming out of my interest in the characters, or the plot, or the kind of language I’m using, but is more simply a property of the book’s vibe of being alive. By that I mean not just how Elizabeth Knox the writer feels about human existence, but how the untethered, reactive, feeling entity, who is making it all up, feels at that particular moment, the moment of beginning the book, the moments of continuing the book. The book that is not a calibration of existence, but one day with a certain kind of weather, a memorable whole, like the interval between waking up and going to sleep. What I think I find in the novels I’m most excited by, and what I’m after in my own work, is a vibe of being alive that belongs generally to – well – I want to say each writer, but of course not all writers have one. Perhaps each considerable writer has one. And by considerable I don’t mean literary, I mean a writer whose vitality has been transmitted to their work. I can make compelling arguments for the vibe of life of Lee Child, or Georgette Heyer, just as I can for Hillary Mantel, Elizabeth Gaskell or Margaret Mahy. This vibe of life is one of the reasons we choose to be constant readers of certain writers. We like what they do, but we also like the way they make us see the world, or feel about it. We like how they make us feel when we are in their world, and therefore how we feel once we’ve finished the book, and are returned to our everyday, with something about our sensibilities, our thought processes, our grit and appetite, altered. That’s my explanation of why we love and cleave to particular authors: their vibe of life. But it isn’t a satisfactory explanation of what, if you’re a novelist, you’re looking for in each of your own books as it yields its purpose is to you. I think of that thing as the book’s aura: borrowing from the new-age. A glow coming off something, which belongs to its life and its character, and tells us something about where it’s been, even if it’s never been anywhere. A book begins, and it hasn’t been anywhere. Sometimes a book begins whose degree of never having been anywhere before its appearance feels as if it’s in the territory of Annunciation and Nativity.

I am reminded of the afternoon when our son Jack finally appeared in my hospital room at Wellington Women’s. He’d been in neonatal for two days, and because of blood loss and my healing caesarean incision, I’d only visited him to breastfeed. He turned up very suddenly, at dinner-time, because, while eating her dinner, his mother had begun sobbing that she wanted her baby. And then his father started crying too. I figure we must have been overheard. Jack appeared twenty minutes later, in his plastic cradle. They put him between my bed and Fergus’s chair, and we proceeded to get cricks in our necks just staring at him. One thing we couldn’t take our eyes off was his quizzical and daunting single eyebrow lift. His left eyebrow would go up as if he couldn’t quite believe what he was being presented with. And Fergus remarked that he thought he had cultivated that expression himself over many years. But Jack was born with it. And perhaps Fergus had been too, and might that not mean that his character was shaped by his facial expression rather than the other way around?

There is the idea that a soul comes into the world with the body, that the soul is unstained, but somehow perfectly formed, although the child still has to grow as a person in the world. That idea may be a bit of Western dualism, but at least to some extent it rises out of observation: the marvel of being surprised by a grandparent’s expression on a toddler’s face. Not just the shadow of an expression, but a thing so powerfully reminiscent that it is as if the expression has arrived containing the whole texture of the grandparent’s life and experience.

There are books that, when you’re their author, seem to appear in the same way, stainless and finished, rather than formed in the forge of writing, as if you, the writer, hadn’t sat there with all the hard labour and hard thinking of making the book’s body. No – the book arrives trailing clouds of glory as if pencil on paper have summoned hitherto invisible realities that want to organise themselves out of nothing, using a writer’s own character and experience.

*

From very early in my life I had a delight in how things were connected. Connected in the world by use and influence, and how I was able to connect them myself in my head. I think my delight had something to do with my puzzlement at my stupidity when it came to writing – that is, writing as opposed to reading. I’m certain now that I had dysgraphia of the dyslexic type. I could read, and comprehend what I’d read, and verbally answer questions about what I’d read, and I could read out loud, but I could scarcely write. It was natural for all my too many primary schools to assume that, since I could read, my writing could only be laboured and abysmal because I was lazy, stubborn and uncooperative. It was the 1960s, and I was a girl, so pains were never taken. For example, when in standard two I was asked to produce two pages on the life cycle of a butterfly, I produced two pages of two words per line, in columns down the left and right hand side of the page, the teacher decided I was being either insolent or indolent. But it was like this: whenever I had a pen my hand, I also had a great glass wall in front of me. I was all in and no out so, although I was reading and thinking and making connections, whatever I learned I had to hold in my head, like water in cupped hands, waiting on the cup, the bucket, the lakebed.

My mind now pretty much works like every one else’s, but is shaped by this early intense practice of recognising how information connected up so that it might support itself instead of requiring me to support it by recording all its facets as they revolved in empty space. My mind has a very strong habit of seeing patterns, because a pattern is easier to hold in your head than its pieces.

Stories have legacies in our limbic systems. Something that is there for any storyteller to use. The audience doesn’t need to know about earlier appearances and interpretations of a particular story – of an invisible monster, a human-shaped monster, a charming human-shaped heart-usurping monster, a monster made by an ambitious scientist, a monstrous God who never answers prayers, or the animal who talks and still curls up beside you like an ordinary cat, but who isn’t there the moment it’s most wanted. Of course it’s nice for the audience to know – to have the deep, nuanced, textured experience of the story because of all the connections it makes. Constant readers, or watchers, people with a degree of appetite and experience and a good memory, get stuff when you give it to them. Those people know that they haven’t learned most of what they know in order of its appearance in the world. They understand they might have met the monster in a joke, before meeting it in its myth.

The great and ancient beast we encounter in a television programme might owe much to H G Lovecraft’s Cthulhu, but the energy of that creature is also the inheritance of all people in a house or a landscape with older occupants. It’s our sense of how recently we’ve been the pinnacle predator, and how tenuously we are a pinnacle predator whenever we’re by ourselves. It’s our short period of remove from the time when we had no news of what was on the other side of the river, or why the mountain in whose shadow we lived would sometimes growl and glow. We may have left much of that behind us – or at least know what’s choking us when the wall of ash washes over us. Yet as surely as being in fear and uncertainty can leave its mark on a developing child’s DNA so that child’s children will inherit a poorly extinguished anxiety, then our stories, and our response to them, have been shaped by all those years of not knowing what it was we could hear at night, behind the wind.

I first met one of my favourite monsters in a joke. At Christmas when I was nine someone gave my mother a card with the three wise men on it, two of them pink with anger and embarrassment, saying to the third, who was holding one end of a rope: ‘We said frankincense . . .’ Then, when the card opened, there on the end of the rope was a louring, greenish monster with bolts in his neck.

I didn’t get the joke. But I knew it was a joke, and a story. Seeing my intrigue Mum explained Frankenstein’s monster. And, since she liked her facts straight, and was the kind of mother who took pains to make sure they were, she also explained how Frankenstein was the man who made the monster, not the monster, who had no name, and how lots of people got that wrong. I’d already realised there was some connection between the monster and the Gruesome Twosome of the Hanna-Barbera Wacky Races, a cartoon about a cross-country race, where the Gruesome Twosome drove a car that looked like a haunted house. One of the Twosome was a massive, monster-like individual with a bowl haircut and a turtleneck sweater – a kind of 60s hipster Frankenstein’s monster. I made that connection. I began to build up a concordance of the story. A concordance which in time assembled itself in order of provenance – in this case Mary Shelley’s book, a product of a ghost story challenge at the Villa Diodati with Shelley and Claire Clairmont, Lord Byron and Dr Polidori. First there was the book, and then later appearances, canon and otherwise and, as with all my concordances, the information was also in order of what mattered most to me. I did that throughout my childhood and teens, and retained my habit of accepting the premises of an invention, or at least waiting to see how things might fit together. It was clear to me that there were no lame ideas. If an idea was limping its shoes might arrive at any moment. Its shoes, its horse and carriage, its rocket ship, its wings. Which isn’t to say that the adult me hasn’t thrown up her hands in disgust when faced with a story that is half-baked or inconsistent or derivative – derivative rather than open to influence – or, worst of all, a story that stacks its dice.

An acceptance of premises is the absolutely necessary prerequisite of the willing suspension of disbelief, that which lets us enjoy stories and not be those people who like to say, with an uneasy superiority, that they only read non-fiction. Because they ‘want to learn something’.

It’s the existence of all my concordances that have determined my mode of operation as a writer, how I like to take a thing, or more often several things, with the charge of a mythical legacy, and use them to my own purposes. Because they are attractive to me and I want to pick them up and handle them. Because they are meaningful to me and I want to get into conversation with them. Because they are comforting to me and I want to slip them under my pillow when I sleep.

*

So. Why write? When it’s often very difficult?

Because if you’re lucky, and you keep at it long enough, and honestly, if you stay by the sundial, and don’t chase any of the things beckoning you from the ends of the avenues – like your own insufficient idea of fame; or money; or the approval of your family and admiration of your friends; or the admiration of your community, or arts funding bodies, or the public, whoever they are – if you stay by the sundial, the sun will come, will show you your shadow, and give you the time. Then, if you’re very lucky, it might give you your Absolute Book.

November 16, 2016

While you’re about it contemplate werewolves

image Jack Barrowman

A conversation between Elizabeth & Sara Knox

This conversation took place in March of 2007. It’s a planning session, on Skype, between me and my sister Sara; she in her flat in a western suburb of Sydney, me in Wellington; both of us lying in bed in the dark, with cats. The planning was for a session of the surviving episodic version of the imaginary game that we had been playing for 34 years.

The continuous saga version of the game came to an end in 1994. In the episodic version we’d use our characters in a new story, with one-time-only histories and names. I want to say that we’d reuse their souls, as if this is transmigration. But perhaps it’s more helpful to remind you of Blackadder, each season set in a different period, but having characters with the same faces, doing different things, but being recognisably like their ancestors.

Each of our people has a continuum to their character. So, for example, Fernando is at one end of his continuum pretty much an Iago, and at the other a charming, self-loving, competent man, with a bit of an attitude problem. These malleable and multifaceted characters people our game. This conversation is Sara and I coming up with a story to play. What we came up with took up around 40 hours of playing, on nine nights, over two and a half months.

Here we discuss what kind of story might entertain us enough for a sustained period of play. But we also consider what makes a good story, and what kinds of stories we like and dislike — referring to books, television, our own fiction. It’s a mad private conversation with public connections and some cultural savvy.

And how did I come to have this recording?

When Sara went to live in Australia in 1992 the game had gone on only when she was at home on holiday. Then in 2004 Skype arrived, and we assumed playing regularly. About a year later I found a software that could record Skype conversations and I started taping our playing and, later, our planning too. I have hundreds of hours of recordings. I made and kept them just for us — or, as I imagine it, for me, bed-bound in the hospital wing of a rest home, as my mother was for the last 18 months of her life. I’ll have audiobooks to entertain me, and my recordings of our younger selves, and of them, our people, speaking and acting, thinking and feeling. And alive. All accompanied by asides about friends, family, work, books, TV, politics; by Fergus coming in with a cup of tea, or Jack warning me he’s about to reboot the modem; plus Sara untangling her cat from the Venetians, or going out to put her chickens in their coops; and noises off: Wellington gales and Sydney rainstorms.

I transcribed this planning session so I could use it for a World Building workshop I taught at the Auckland Writers Festival in 2014. I used it as a guideline to explain my process. This is pretty much what we said, minus breathless repetitions, and cackling.

[cackles]

*

Elizabeth: Family plots and non-family plots. Plots where people already know each other and are obliged to pay attention to one another, and plots where they just meet and have to work one another out.

Sara: I thought something about the war. We haven’t done the war yet this time around.

E: Wars are difficult. Easier to write than to play. And I avoid them in writing.

S: You don’t avoid them. You lie. There’s the war in Glamour and the Sea.

E: But it’s the home front, New Zealand. There’s After Z-Hour with actual warfare. But that’s it. No more wars.

S: I might be having a few battles in my next one. But they’ll all be nineteenth-century. The siege of Omdurman.

E: Well, I do have internment camps in Texas at the end of my Vintner sequel. So that’s the war. Damn. Only because it would happen, since the idiot has a German passport. Is the idiot going to think: ‘I, Xas, the angel without wings, must get US citizenship’? Is he going to think that? Nah.

S: Why were you thinking of werewolves?

E: That’s just one of my lines. I always run it past you, and you go, ‘I’m not really into werewolves.’

S: I wouldn’t say I was categorically against werewolves.

E: I had my werewolf-on-death-row plot. You know, the person who tore their whole family apart, and they’re a trauma-triggered werewolf rather than a lunar cycle one. That was an idea. But you said you can’t do death row.

S: You can’t because there are no interactions on death row. Not really.

E: Right. So no werewolves.

S: Werewolves aren’t an idea in themselves. If you’re going to do them then it’s better to go traditional, with the forest clearing and gypsy wagons and the this and the that. The ‘I am happening with werewolves.’

E: Like the ‘I was bitten by a werewolf and now I’m a werewolf’? Nah.

S: See? You’re not sure about werewolves yourself. I was actually thinking of a speculative fiction kind of plot where there are tour guides who take people like . . .

E: You’re going to say time travel.

S: Kind of like Christmas Past Christmas Present and Christmas Future. Trained people who take you back into your life, or someone else’s, an ancestor’s, or something inter-dimensional. I didn’t really think what.

E: So, a skilled practitioners story.

S: Yeah. A little bit like Dreamhunters really.

E: Okay. Tour guides in time. That’s a possible. Madeline and I once did a stupid one where — for some strange reason — people from different time periods ended up rocketing through the ages, collecting one another as they went. So they’d just appear in someone’s life, and when they moved on again the someone would go with them, helplessly. They couldn’t work out why they were together. They all disapproved of one another because of different social mores. So there was a Southern belle and a flapper who couldn’t see eye to eye. There was a cyborg law enforcer and a hippy — that kind of thing.

S: That sounds kind of strange.

E: I can’t remember whether I came up with a reason they were loose in each other’s slipstream. I might have. Can’t remember what it was. We also did a good one with a group of ordinary people who were chosen to decide the fate of humankind — shut in a room while the world slowly disappeared.

S: We don’t want to be shut in a room while the world disappears. That’s too much like that one we’ve done already.

E: What? The one about the royal family?

S: No, not the royal family, the one with the invisible creature and trapped people.

E: Oh yeah. The Wake.

S: Already done that.

E: And it had an alien. So we’ve had aliens, though all aliens have different permutations.

S: We’ve had aliens, we’ve had vampires, we’ve had fairies — we always have these things. The food groups.

E: Okay — how about a Galactica type thing. Though I don’t know how far you want to go with some cylon-like threat. How about if we do a fleet that has escaped from the destruction of their planet who actually get to earth. So — do it from the arrival. Do the refugees, asylum seekers. Do their mortal enemies in pursuit and still trying to wipe them out — or the threat of the enemy’s arrival. Does earth want to inherit other people’s enemies?

S: Or not.

E: Too grand? I wonder what Galactica is going to do with that final five. Oh dear oh dear oh dear. And is Baltar going to get saner or madder.

S: When he appears to Six he’s never very nice to her. When she appears to him he’s often much nicer.

E: So her version of him is nastier. Poor Six.

S: Poor all of them

E: Yeah. Except Adama who needs a smack for being so mean to Apollo.

S: He was particularly mean in the last one.

E: What is his problem? He’s probably a cylon.

S: I’m wondering is my cat a cylon? . . .

E: Okay, so, if a bunch of aliens turned up in our Solar System, the latest asylum seekers . . .

S: Nah. It really doesn’t do it for me.

E: Okay. So. All right.

S: Tribes. Native Americans.

E: Tribes that aren’t Native Americans.

S: Anthropologists. Pueblos.

E: Human anthropologists with aliens. I always like the whole Star Trek thing where the starship crew has to deal with, and be diplomatic to, badly behaved aliens. Be terribly polite to people who like to wear necklaces made out of their enemies’ teeth and ears.

S: But there are enough people who do that kind of thing in real life.

E: But if you do those people you get into real politics. There is a reason I write fantasy you know!

S: Because you don’t want to do real politics?

E: I don’t mind doing real politics in a sequence. I don’t mind exploring, it’s just . . .

S: Yeah. Writing novels is great for all sorts of things. But there’s a whole set of things I don’t want to do.

E: I don’t like crisis fiction. I hate it intensely. That’s what I want to avoid.

S: What’s crisis fiction?

E: Books that get their dignity and importance from discussing the atrocities of the past, or foreign parts. Some comfortable bloke writer writing a novel about some brave soul playing a stringed instrument in the ruins of Sarajevo. The stakes are built in. High stakes and high-mindedness. There’s all these readymade claims to seriousness.

S: So — like someone contemporary writing a novel from the point of view of a holocaust survivor? Like (title redacted by author redacted). That was a pernicious piece of shit. God I hated that so much.

E: And I had to watch people oozing all over her at a festival. And she was so leaden as a human being. Leaden, self-regarding.

S: There’s the whimsical crisis books. Like Augustin Burroughs’ Running With Scissors.

E: But isn’t that autobiographical? Like Angela’s Ashes. I think that’s not so bad. Anything done well isn’t bad.

S: Yeah, I guess. And I liked Mary Karr’s The Liars Club.

E: That’s kind of a personal crisis story. I liked that too. But there’s always a danger when so much of the book’s dignity comes from the claims of suffering. It’s a real balancing act.

S: So Crisis Fiction is fiction with borrowed gravitas.

E: Yes. And there’s so much of it around. Which is one reason I write fantasy. I go, ‘I’m going over here and doing this’. Because, boy, fantasy does not have gravitas. Even when it has gravity.

S: There are people doing that. Like Beyond Black, Hilary Mantel.

E: Literature and non-realist.

S: But it’s realist fantasy.

E: The real world and the supernatural, a bit like Vintner. But she’s in her own class. She can do anything.

S: She’s a great writer.

E: And she is anti-bullshit.

S: I like writing historical fiction because it gets away from so much. You can use the tools of real invention. But, anyway, we need an idea. Anthropologists.

E: I don’t know enough about anthropology.

S: Trained ghost squads.

E: Okay . . .

S: What say you had a highly trained, engineered, secret . . .

E: Troop of ghost-hunting ghosts? Or dead, the corporal and incorporeal dead.

S: Ghosts who bust ghosts.

E: They’re the Thin Dead Line.

S: They are a Pentagon innovation because there’s some ghostly threat.

E: But how would the Pentagon have recruited them? Did the Pentagon create them by killing people under special ghost-creating conditions?

S: Maybe they created some and recruited others.

E: So are they put in play against dead demonic forces? This is a good plot. I smell good plot all over it.

S: If maybe the conditions of existence were so bad that the world’s population has been seriously reduced and the only way you can up your fighting corps is to raise bodies.

E: Corpse Corps. So this is like Garth Nix. You’re talking about necromancy. You resurrect bodies. That’s also the Welsh myth of the black cauldron that Lloyd Alexander uses. An army of the dead.

S: I wasn’t so much thinking of resurrected bodies. I was thinking that part of the thing of how they fight would have to be to do with their ghostliness. Resurrected soldiers is boring.

E: So we’re not talking about a small secret group that battles evil forces. We’re talking about a whole system and armies.

S: You could still have the elite shock troops. Because maybe some people are better at being dead than others.

E: That goes without saying if some people are better at being alive. So — I was just wondering if we could work in reanimated corpses too, because that’s always good and gross.

S: Well, that could be the lowest grade. The grunts. This has to be a situation of total war.

E: But would it be total war? I’m worried about the scope.

S: Well, you have societies that are totally opposed to one another but can’t raise an army anymore.

E: But does society let that happen? Do mothers let their dead children be recycled to fight? It would only work if all the living were an elite, who live so long and in such good conditions that they’re like gods of ego. There’s plenty for everyone, but because the people are horrid they still settle conflicts of interest by combat — at no risk to themselves.

S: Or, alternately, you have an off-world alien threat and the only way you can fight them is by using people who are dead. Ghosts.