Jack Ross's Blog

November 29, 2025

Tim Powers (2): My Brother's Keeper

Tim Powers: My Brother's Keeper (2023)

Tim Powers: My Brother's Keeper (2023)It's roughly ten years since I wrote a post about American fantasy novelist Tim Powers. I did make a further brief mention of him in a piece on psychogeography a few years ago, but nothing much since. Am I my brother's keeper, after all?

Tim Powers: Alternate Routes. Vickery & Castine #1 (2018)

Tim Powers: Alternate Routes. Vickery & Castine #1 (2018)He's not been idle in that time: that's putting it mildly. Anyone would think he was doing it for a living! He's published a trilogy of books (with, apparently, a fourth yet to come) about a couple of Mulder and Scully-like investigators - Vickery and Castine - and their explorations of the Los Angeles motorway system and other haunted sites around the city.

Tim Powers: Forced Perspectives. Vickery & Castine #2 (2020)

Tim Powers: Forced Perspectives. Vickery & Castine #2 (2020)"The Ghosts of the Freeway are rising," as the cover of the first of them proclaims.

Tim Powers: Stolen Skies. Vickery & Castine #3 (2022)

Tim Powers: Stolen Skies. Vickery & Castine #3 (2022)He's also put out a substantial collection of his short stories and novellas to date: Down and Out in Purgatory. As you can see from the listings at the bottom of this post, it's not complete, but still a pretty comprehensive selection of his work in these forms over the years.

Tim Powers: Down and Out in Purgatory (2017)

Tim Powers: Down and Out in Purgatory (2017)The main event in these years, however, would have to be his new novel about the Brontës, My Brother's Keeper.

Tim Powers: My Brother's Keeper (2023)

Tim Powers: My Brother's Keeper (2023)•

Tim Powers: The Stress of Her Regard (1989)

Tim Powers: The Stress of Her Regard (1989)Set - more or less - in the same magical universe as his earlier books The Stress of Her Regard and Hide Me Among the Graves, My Brother's Keeper continues the conceit of an underlying occult explanation for the odd behaviour of various constellations of closely related Romantic poets and artists: the Shelley circle in The Stress of Her Regard, the Pre-Raphaelites in Hide Me Among the Graves, and now the three visionary sisters of Haworth Parsonage ...

Tim Powers: Hide Me Among the Graves (2012)

Tim Powers: Hide Me Among the Graves (2012)Perhaps Charlotte, Emily, Anne and their hapless brother Branwell are not quite so well known among fantasy readers as they are to fans of Victorian fiction, however, given the bold legend:

Howarth.

Yorkshire.

1846

on the back of my paperbook copy of the book. I suppose "Haworth" might well look like a misprint for "Howarth" if you hadn't been brought up on the arcane lore of the Brontës.

Frances O'Connor, dir.: Emily (2022)

Frances O'Connor, dir.: Emily (2022)I wrote an earlier post about about what sceptical historian Lucasta Miller called "The Brontë Myth" à propos of Frances O'Connor's 2022 film Emily .

Emily, the fiercest and most enigmatic of the three sisters, is at the heart of Tim Powers' novel, too, and the similarities between the two projects are quite revealing. Both O'Connor and Powers gift Emily with an illicit love affair: O'Connor with timid young curate William Weightman, Powers with surly (albeit reformed) werewolf Alcuin Curzon.

Both authors are at a bit of a loss at how to deal with Emily's elder sister Charlotte, so O'Connor turns her into a tedious, uncreative nag, while Powers makes her the only one of the Brontë children not to make a childish pact with the powers of darkness by smearing their blood on a rock in a nearby cavern.

Both take considerable liberties with the well-documented realities of the Brontë's lives, but in O'Connor's case this involves rewriting history to a startling degree, whereas Powers sticks to his usual artistic principle of feeling free to invent reams of extra supernatural action just as long as he's governed by the actual canonical timeline of his subjects' lives.

Branwell Brontë: Anne, Emily & Charlotte Brontë (1834)

Branwell Brontë: Anne, Emily & Charlotte Brontë (1834)I guess it's a matter of taste, but I myself found O'Connor's inventions more intrusive because they had the cumulative effect of somehow normalising the oddities of Emily's personality. As I said in my previous post:

I share director (and script-writer) Frances O'Connor's fierce appreciation of Emily's genius - she is, for me, the pick of the bunch, and her novel a masterpiece on a quite different level from Charlotte's and Anne's more numerous works ... She's the only one of the three sisters who's ever been regarded as a poet of distinction, and the ... clockwork machinery of her sublime Gothic novel belies any attempts that have been made since to write it off as hysterical melodrama.However, "the film's decision to show Charlotte sitting down to write her own novel in the wake of Emily's death, and thus - in a sense - carrying on her work, just doesn't seem a necessary fiction to me." I don't see what it adds to our sense of Emily's deep strangeness as a human being to invent a lot of belittling lies about the other sisters.

As Carrie S. remarks in her enthusiastic review of Tim Powers' phantasmagorical reinvention of the Brontë saga:

I love my Brontës and I get so annoyed when either adaptations of their work or stories based on their lives get EVERYTHING WRONG ... My Brother’s Keeper is an eerie story involving the Brontë family, werewolves, and warring cults, and, darn it, it gets everything just absolutely perfect.- Smart Bitches, Trashy Books (6/3/2024)She goes on to quote a comment by fantasy illustrator Michael Hague to the effect that "the more outlandish the the things he wanted to represent, the more convincingly realistic the mundane details must be":

The story works because, first of all, the mundane details feel correct. Things that ought to be heavy do, in fact, cause the characters difficulty when they try to lift them. People have to eat and drink and sleep. Much mention is made of potatoes, either eating them or peeling them or cutting them up. Struggles are as much mundane as mystical. For instance, the characters make frequent references to their efforts to convince local government to move the town’s well uphill from the cemetery –- a real-life problem for the residents of Haworth ... was that the cemetery drained directly into their drinking water.The plot is definitely as busy and complicated as in any of Powers' other novels, but it somehow feels more weighty and serious this time. It was a little difficult to credit that he actually believed in the existence of his Dr. Polidori vampire (in Hide Me Among the Graves) or his stone-disease cursed poet Percy Shelley (in The Stress of Her Regard).

Secondly, the story works because, to me, the portrait of the Brontës, specifically Patrick, Branwell, Charlotte, Emily, Anne, their housekeeper Tabitha and Emily’s dog Keeper, is spot on. Everything they do and everything they say is perfectly in character. As bizarre as the plot is, it actually makes aspects of the Brontës’ lives make more sense rather than less.

Branwell Brontë: Emily Brontë (1833)

Branwell Brontë: Emily Brontë (1833)I don't feel the slightest doubt that he's fallen in love with his own fearless Emily Brontë, though. As she strides across the moors, shooting at lycanthropes and guarding her worthless brother Branwell from the consequences of yet another betrayal, she gradually assumes the larger-than-life status which her admirers (myself among them) have accorded her all along.

If there could ever be such a thing as a human being whose ethical judgement and moral courage is definitively beyond question (for us true believers, at least) it's Emily Brontë - and Powers sets out to substantiate this view. Anne comes out pretty well, too - far better than in the O'Connor film. Admirers of Charlotte will probably be a little disappointed, but there's a good deal of Jane Eyre in Powers' story, too, so they won't feel as disgusted as they did by the lies and calumnies included in in the Emily film.

Emily Brontë: Keeper (1838)

Emily Brontë: Keeper (1838)Nor is it the smallest virtue of Powers' book that Emily's faithful dog has such a big part to play in the story. As Carrie S. succinctly expresses it:

He is a Very Good Dog.Overall, I'd say that My Brother's Keeper is Powers' best book since his defining fantasy novel The Anubis Gates some forty years ago. And given that this one made me cry - though Emily's death tends to do that to me, even in O'Connor's film - I think that it's very probably better.

Chapeau bas, messieurs! as old Doctor Rieux in Camus' La Peste dreams that his readers may someday say when they read the opening sentence of his own novel: "Hats off, boys!"

Tim Powers: The Anubis Gates (1985)

Tim Powers: The Anubis Gates (1985)•

Emily Brontë: The Annotated Wuthering Heights (2014)

Emily Brontë: The Annotated Wuthering Heights (2014)Another surprisingly difficult feat which Powers pulls off with style and panache is weaving so many vital details from Wuthering Heights into the even wilder action of My Brother's Keeper.

"Heathcliff's lost years" is the approach many writers have taken to the problem of how to continue - or supplement - the storyline of Emily's masterpiece. Powers takes the opposite tack. He makes the character Heathcliff a dim avatar of the actual demon "Welsh", who has haunted the Brunty family (renamed Brontë, accordingly to Powers, not by analogy with Admiral Nelson's title as Duke of Bronte, a commune in Sicily, but as an invocation of Brontes , one of the three Cyclopes who forged Zeus's thunderbolt) for three generations.

I won't go into all the ins-and-outs of the foreshadowings and connections Powers manages to excavate from Emily's plot, but suffice it to say that a rereading of Wuthering Heights, perhaps in Janet Gezari's 2014 edition, might help to appreciate that aspect of his work.

For the rest, I'm a little surprised to see that Powers has managed to produce yet another novel since My Brother's Keeper, set - this time - among the American expatriates in 1920s Paris. I suppose when you're on a roll it pays to keep going. In any case, I look forward to reading what mayhem he's managed to wreak amongst Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and the other Moderns:

Tim Powers: The Mills of the Gods (2025)

Tim Powers: The Mills of the Gods (2025)•

Tim Powers (2013)

Tim Powers (2013)(1952- )

Novels:

The Skies Discrowned [aka Forsake the Sky, 1986] (1976)Included in: Powers of Two: The Skies Discrowned & An Epitaph in Rust. 1976, 1986, 1989. Framingham, MA: The NESFA Press, 2004. An Epitaph in Rust (1976)Included in: Powers of Two: The Skies Discrowned & An Epitaph in Rust. 1976, 1986, 1989. Framingham, MA: The NESFA Press, 2004. The Drawing of the Dark (1979)The Drawing of the Dark. 1979. London: Granada, 1981. The Anubis Gates (1983)The Anubis Gates. 1983. London: Triad Grafton Books, 1986. Dinner at Deviant's Palace (1985)Dinner at Deviant's Palace. 1985. London: Grafton Books, 1987. On Stranger Tides (1987)On Stranger Tides. 1987. New York: Ace Books, 1988. Polidori series:

Fault Lines series:

The Stress of Her Regard (1989)The Stress of Her Regard. 1989. London: HarperCollins, 1991. Hide Me Among the Graves (2012)Hide Me Among the Graves. 2012. Corvus. London: Atlantic Books Ltd., 2013.

Declare (2001)Declare. 2001. New York: HarperTorch, 2002. Three Days to Never (2006)Three Days to Never. 2006. William Morrow. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2013. Medusa's Web (2015)Medusa's Web. 2015. Corvus. London: Atlantic Books Ltd., 2016. Vickery and Castine series:

Last Call (1992)Last Call. Fault Lines, 1. 1993. New York: Avon Books, 1996. Expiration Date (1995)Expiration Date. Fault Lines, 2. London: HarperCollins, 1995. Earthquake Weather (1997)Earthquake Weather. Fault Lines, 3. 1997. London: Orbit, 1998.

My Brother's Keeper (2023)My Brother's Keeper. 2023. Head of Zeus. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2024. The Mills of the Gods (2025)

Alternate Routes (2018)Alternate Routes. Vickery & Castine, 1. A Baen Books Original. Riverdale, NY: Baen, 2018. [Uncorrected Proof Copy] Forced Perspectives (2020)Forced Perspectives. Vickery & Castine, 2. A Baen Books Original. Riverdale, NY: Baen, 2020. Stolen Skies (2022)Stolen Skies. Vickery & Castine, 3. A Baen Books Original. Riverdale, NY: Baen, 2022.

Short Story Collections:

Night Moves and Other Stories (2000)Itinerary (1999)Night Moves (1986)Pat Moore (2004)The Way Down the Hill (1982)Where They Are Hid (1995)[with James P. Blaylock] The Better Boy (1991)[with James P. Blaylock] We Traverse Afar (1995) [with James P. Blaylock] The Devils in the Details (2003) Introduction (Tim Powers)Through and Through (Tim Powers)Devil in the Details (James P. Blaylock)Fifty Cents (James P. Blaylock and Tim Powers)Mexican Food: An Afterword (James P. Blaylock) Strange Itineraries (2005) Itinerary (1999)The Way Down the Hill (1982)Pat Moore (2004)[with James P. Blaylock] Fifty Cents (2003)Through and Through (2003)[with James P. Blaylock] We Traverse Afar (1995)Where They Are Hid (1995)[with James P. Blaylock] The Better Boy (1991)Night Moves (1986) Strange Itineraries: The Complete Short Stories of Tim Powers. Introduction by Paul Di Filippo. San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 2005. The Bible Repairman and Other Stories (2011) The Bible Repairman (2006)A Soul in a Bottle (2006)The Hour of Babel (2008)Parallel Lines (2010)A Journey of Only Two Paces (2011)A Time to Cast Away Stones (2008)The Bible Repairman and Other Stories. San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 2011. Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Salvage and Demolition (2013)The Bible Repairman (2006)Appointment at Sunset (2014)[with James P. Blaylock] The Better Boy (1991)Pat Moore (2004)The Way Down the Hill (1982)Itinerary (1999)A Journey of Only Two Paces (2011)The Hour of Babel (2008)Where They Are Hid (1995)[with James P. Blaylock] We Traverse Afar (1995)Through and Through (2003)Night Moves (1986)A Soul in a Bottle (2006)Parallel Lines (2010)[with James P. Blaylock] Fifty Cents (2003)Nobody's Home: An Anubis Gates Story (2014)A Time to Cast Away Stones (2008)Down and Out in Purgatory (2016)Sufficient Unto the Day (2017) Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers. Foreword by David Drake. Introduction by Tony Daniel. 2017. Riverdale, NY: Baen, 2019.

Chapbooks:

Night Moves [novella] (1986)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) [as 'William Ashbless', with James P. Blaylock] The Complete Twelve Hours of the Night (1986) [by Phil Garland] A Short Poem by William Ashbless (1987)Where They Are Hid [novella] (1995)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) [as 'William Ashbless', with James P. Blaylock] On Pirates (2001) [as 'William Ashbless', with James P. Blaylock] The William Ashbless Memorial Cookbook (2002) The Bible Repairman [novella] (2006)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Nine Sonnets by Francis Thomas Marrity (2006) A Soul in a Bottle [novella] (2006)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Three Sonnets by Cheyenne Fleming (2007) A Time to Cast Away Stones (2008)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) 'Death of a Citizen.' In A Comprehensive Dual Bibliography of James P. Blaylock & Tim Powers, by Silver Smith (2012) Salvage and Demolition [novella] (2013)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Nobody's Home [novella] (2014)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Appointment on Sunset [novella] (2014)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) Down and Out in Purgatory [novella] (2016)Included in: Down and Out in Purgatory: The Collected Stories of Tim Powers (2017) More Walls Broken [novella] (2019)The Properties of Rooftop Air [novella] (2020) After Many a Summer [novella] (2023)

Secondary:

[Katz, Brad. “An Interview with Tim Powers (21/2/96).” Brow Magazine (1996).]

•

Tim Powers: The Last Call Series (1992-1997)

Tim Powers: The Last Call Series (1992-1997) Tim Powers: The Vickery & Castine Series (2018-2022)

Tim Powers: The Vickery & Castine Series (2018-2022) Pierre Mornet: The Brontës’ Secret (2016)

Pierre Mornet: The Brontës’ Secret (2016)•

Published on November 29, 2025 14:20

November 16, 2025

Favourite Children's Authors: John Masefield

John Masefield. The Midnight Folk (1927)

John Masefield. The Midnight Folk (1927)[Illustrated by Rowland Hilder (1931)]

When it comes to favourite children's authors, John Masefield's classic kids' book The Midnight Folk , along with its even stranger and more magical sequel The Box of Delights , must certainly have earned him a place in the pantheon.

John Masefield: The Box of Delights (1935)

John Masefield: The Box of Delights (1935)[Illustrated by Judith Masefield (1935) & Faith Jaques (1984)]

I remember recommending these books to Professor D. I. B. Smith while he was supervising my Masters thesis on the novels of John Masefield. Don couldn't see much in them. "Maybe you had to be there," he said. I suppose he meant that unless you read such books at just the right age, when their mixture of talking animals and ambiguous dreamscapes can be assimilated at face value, they're unlikely ever to exert the same charm.

That may be so. But I was brought up on them, and for me they're just as compelling as Through the Looking Glass or The Wind in the Willows (or, for that matter, Norman Lindsay's The Magic Pudding, another staple of our Antipodean childhood).

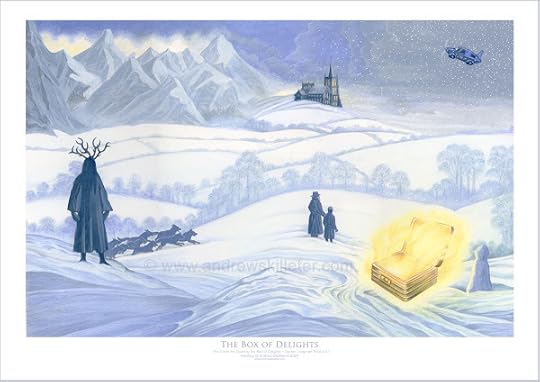

What I liked best in The Box of Delights were the little adventurous vignettes which could only be reached by means of the mysterious box itself. Riding with Herne the Hunter, observing the aftermath of the Siege of Troy, and visiting the court of King Arthur, were all real experiences sealed within this strange miniature world created by the (fictional) Medieval Magister Arnold of Todi.

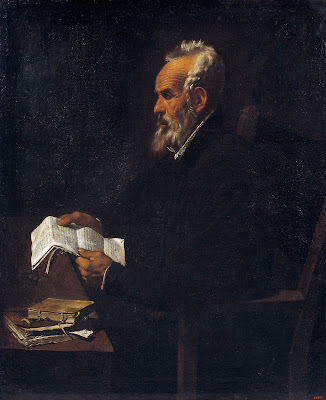

Francisco Ribalta: Ramon Llull (1620)

Francisco Ribalta: Ramon Llull (1620)The Punch-and-Judy man Cole Hawlings, who guides Kay for much of his quest is, we eventually learn, a contemporary of Arnold's, Ramon Lully - or Ramon Llull (1232-1316): a real person this time - who'd attempted to swap his own elixir of life for the box many centuries before.

I'd never heard of Llull before reading The Box of Delights, and when I began to find out more about him years later, reading France Yates's The Art of Memory, I felt as if the hidden depths of Masefield's book were finally beginning to reveal themselves to me.

Renny Rye, dir.: The Box of Delights (BBC, 1984)

Renny Rye, dir.: The Box of Delights (BBC, 1984)If only these mysteries had formed more of a part of the BBC TV adaptation of the book, I would probably have enjoyed it more. As it is, I kept on waiting for my favourite scenes to appear, and was immensely disappointed when they didn't. I'm sure it has its charms for those who watched it as children, but - rather like Don Smith with the book itself - it holds less appeal for me.

In his excellent essay on this particular "musty book" on his Haunted Generation blog, Bob Fischer sees the narrative as one long warning against dwelling too much in the past:

Our collective concept of the past is idealised, even mythologised, and allowing it to intrude into modern life at the expense of the present (no matter how dreary the latter may seem) will inevitably lead to sickness and corruption.Certainly the temptation to freeze the past in a single small compass - as both Arnold and Ramon have attempted to do - is seen as a vital mistake in Masefield's book. It may not be necessary to go as far as Maria, the youngest of the Jones children, who are staying with Kay for the holidays:

Christmas ought to be brought up to date. It ought to have gangsters and aeroplanes, and a lot of automatic pistols.This atmosphere of 1930s pulp fiction, too, is shown to have its perils, when Maria is herself kidnapped by the desperate gang who are after the box. If there is an overall theme in the book, it might be the importance of maintaining a live tradition - the tradition of Christmas in the Cathedral, for instance - rather than neglecting it either through soul-sapping nostalgia or blatant greed.

Andrew Skilleter: Cover for The Box of Delights (2024)

Andrew Skilleter: Cover for The Box of Delights (2024)•

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)In keeping with this idea of the necessity of maintaining live traditions, another important creative resource for Masefield throughout his career was the Arthurian legend. There's a definite overlap between his work purely for children, and his work in this particular part-historical, part-fantastic region of the imagination.

The Knights of the Round Table appear in some of Kay's magical journeys in The Box of Delights, and the stories of King Arthur and Camelot also form a major component of Masefield's fascination with the psychogeography of English places: his birthplace Ledbury, in Herefordshire, for instance, as well as Boar's Hill, near Oxford, where he lived after the First World War.

My own interest in Arthur, sparked by an early reading of the book All About King Arthur by historian (and mystic) Geoffrey Ashe, may seem rather more anomalous, given I was born and brought up in the South Pacific. Whatever the motivations behind it, though, it led me to look out for as many versions as possible of the Arthurian mythos in everything I read subsequently.

The story itself - with its strong underpinning of jealousy, betrayal, and ultimate doom - is, I would have to concede, not one that's entirely comprehensible to children. How are they meant to empathise with characters such as Guinevere, Iseult, or (for that matter) Mordred?

I certainly didn't. But the attempt to do so helped me a lot with my own growing up. Neither Rosemary Sutcliff's Arthur nor Mary Stewart's Merlin - not to mention T. H. White's "Ill-made knight" Lancelot - were straightforward characters, and the stories about them were not especially easy to fathom.

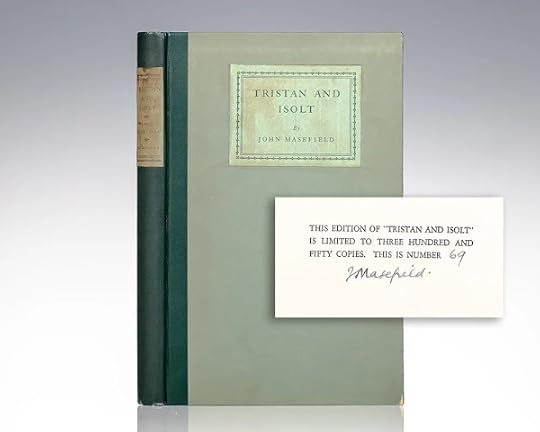

John Masefield: Tristan and Isolt (1927)

John Masefield: Tristan and Isolt (1927)Masefield's version of the Arthurian legend was equally curious and offbeat. On the one hand he seemed determined to claw back to the fifth century roots of these stories. On the other hand, he was drawn to the melodrama of Tristan and Lancelot and the preset, fatalistic love stories they seemed doomed to reenact.

Hence his attempt at the first of these stories in the play Tristan and Isolt. Hence also his attempt at a more complete Arthurian cycle in Midsummer Night and Other Tales in Verse.

John Masefield: Midsummer Night and Other Tales in Verse (1928)

John Masefield: Midsummer Night and Other Tales in Verse (1928)This theme in his work would culminate in his last novel, Badon Parchments .

John Masefield: Badon Parchments (1947)

John Masefield: Badon Parchments (1947)Masefield's fascination with Byzantium was at its height when he wrote this book, so the form that it takes, a series of reports sent back to the Imperial court by Byzantine envoys to the last surviving embers of Roman Britain, in the person of King Arthur and his army, is not as counter-intuitive as it might otherwise appear.

As a novel, though, it's almost nouveau roman-like in its dryness and avoidance of melodrama. Perhaps it was just that he was exhausted with narrative prose by this point - it had, after all, been forty years since he published his first novel, Captain Margaret , in 1908 - or perhaps it was just an experiment that didn't quite come off, but Badon Parchments still seems a curious coda to these two deep fixations of his: Constantinople and King Arthur.

Adam J. Goldwyn & Ingela Nilsson, ed.: Reading the Late Byzantine Romance (2018)

Adam J. Goldwyn & Ingela Nilsson, ed.: Reading the Late Byzantine Romance (2018)•

John Masefield: Martin Hyde: The Duke's Messenger (1910 / 1925)

John Masefield: Martin Hyde: The Duke's Messenger (1910 / 1925)Which is perhaps as good a reason as any to shift our discussion to that earlier era, when Masefield as a young writer was experimenting with different forms of expression - both in order to define the nature of his own talent, and to make a living in pre-war Grub Street. Children's fiction must, then, have seemed one of the more obvious genres for him to try.

It's pretty impressive, even so, that he managed to publish no fewer than four boys' books in the years 1910-1911, before the immense success of his first long narrative poem, The Everlasting Mercy , set him on a more individual path.

The first of them, Martin Hyde , is a rather Henty-esque historical novel about the Monmouth rebellion in the 1680s.

It's an interesting book insofar as it attempts to parallel the romantic atmosphere of Martin's experiences ("We were off. I was on my way to Holland. I was a conspirator travelling with a King. There ahead of me was the fine hull of the schooner la Reina, waiting to carry us to all sorts of adventure ...") with the rather more prosaic nature of everyday life aboard ship:

There you are,' said the mate of the schooner. 'Now down on your knees. Scrub the floor here. See you get it mucho blanco.'The older Martin, who is narrating the story of his earlier life, has various sage reflections to make on this experience, but is honest enough not to attribute them to his younger self.

He left me feeling much ashamed at having to work like a common ship's boy, instead of like a prince's page, which is what I had thought myself.

I will not tell you how I finished the deck. I will say only this, that at the end I began to take a sort of pride or pleasure in making the planks white. Afterwards, I always found that there is this pleasure in manual work. There is always pleasure of a sort in doing anything that is not very easy.As for the book itself, its main virtue is the various ingenious ways Masefield finds to undermine the more facile traditions of boys' adventure fiction, as established by authors such as Ballantyne and Stevenson, with a dose of cold reality: 'You don't know what an adventurous life is', the narrator informs us:

I will tell you. It is a life of sordid unquiet, pursued without plan, like the life of an animal.

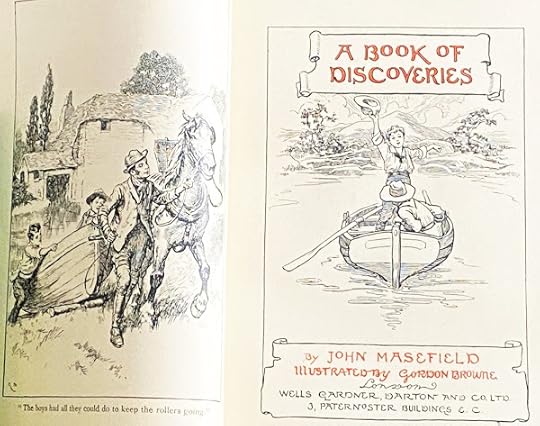

John Masefield: A Book of Discoveries (1910)

John Masefield: A Book of Discoveries (1910)Its successor, A Book of Discoveries , is more in the tradition of books like Richard Jefferies' Bevis: The Story of a Boy (1882) or Kipling's Puck of Pook's Hill (1906) than adventure yarns such as Treasure Island or King Solomon's Mines. It's a kind of bildungsroman, depicting the everyday adventures and explorations of two young boys, Mac and Robin, "on a tributary of the River Tame in the village of Water Orton in Warwickshire."

Their mentor, Mr. Hampton, who catches them trespassing on his land, is (depending on how you look at it) either a tediously didactic and crotchety taskmaster, who lectures the boys incessantly, or an idealised self-portrait of the author himself, itching to correct the erroneous attitudes of the younger generation with a good dose of hard work. Take your pick. Here's a sample of his conversational style:

Xenophon, in his OEconomicus, praises the beautiful order of a big Phoenician ship which he saw at Athens. He makes it clear that even then ships were fitted 'with many machines to oppose hostile vessels, many weapons for the men, all the utensils for each company that take their meals together,' besides the freight of merchandise, and the men themselves. Yet all these things, he says, 'were stowed in a space not much larger than is contained in a room that holds half a score dinner-couches.' How big do you suppose that would be, eh?I like that little "eh?" at the end, as if that's sufficient to transform it all into light banter. Admittedly, it's not all as dry as that, and the boys' finds throughout the book, which include a cave with a number of interesting flints and inscriptions, along with the remnants of a Roman pay-chest surrounded by small heaps of coins, go a long way towards proving Hampton's contention that:

the wonderful discoveries lie under our noses all the time, if we only had the sense to make them.

John Masefield: Lost Endeavour (1910)

John Masefield: Lost Endeavour (1910)I love stories. I prefer them to be touched with beauty and strangeness. I like them to go on for a long time, in a river of narrative; and I like tributaries to come in upon the main stream, and exquisite bays and backwaters to open out, into all of which the mind can go exploring after one has learned the main stream.This passage from a 1944 essay of Masefield's with the Blakean title "I Want! I Want!" is a good description of Lost Endeavour , to my mind the richest - though possibly the least popular - of his pre-war boys' books.

In the chapter of my 1984 MA thesis on Masefield devoted to these books, I describe it as "a Treasure Island as Masefield felt it ought to be":

The parallels are very close – even down to the actual treasure on an island – but Masefield is concerned to show what such a life might actually have been like to experience. None of his villains are likeable – unlike Long John Silver – and his pirates in particular are potrayed as brutal ruffians and animals.His twin protagonists, the gloomy boy Charles and the irresponsible grown-up dreamer Theo, reverse the pattern of the romantic Jim Hawkins and the business-like Squire Trelawny. The pattern of the successful quest for riches characteristic of such tales is also inverted in Masefield's novel, where "the meaning shows in the defeated thing" (as he out in in his much-anthologised poem "The Wanderer").

The value of the book lies in its incidental details, such as this description of a tropical forest:

All a wilderness of green things, a chaos of vegetables. No, it is not a chaos, it is a world of the most exquisite order. Every leaf is turned so as to catch life from its surroundings; the greatest and sweetest and fittest kind of life, either of sun or air or water. Not a blossom, not a twig, not a fruit there but has striven, I will not say with its whole intellect, but with its whole nature, to make of itself the utmost possible, and to give to itself in its brief life a deeper crimson, a more tense, elastic toughness, a finer sweetness and odour. Ah! the life that goes on there, the abundant torrent of life, the struggle for beauty and delicacy ... Ah! that forest. It was cool within there, out of the sun, so cool that it was like walking in a well; a dim, cool, beautiful well, full of pale green water from the sea. The flowers called to me: 'I am crimson,' 'I am like a pearl,' 'I am like sapphires.' The fruits called to me that they tasted like great magical moons."Tell me of your cities", concludes Masefield's narrator, "I tell you of the garden and the orchard, where life is not a struggle for wealth, but for nobleness of form and colour."

John Masefield: Jim Davis (1911)

John Masefield: Jim Davis (1911)Unfortunately these poetic extensions of the possibilities of children's fiction were not really built on in Jim Davis , Masefield's final pre-war essay in the genre.

Like its predecessor Martin Hyde, it's a

traditional boys' book in form – told in the first person by the eponymous hero – and the action unfolds in an early nineteenth century Devonshire village.This time, however, it's a story about smugglers. To do him justice, Masefield tries to stress the reality rather than the romance of so stressful a trade. In fact:

so accurately are Jim's reactions to his sufferings depicted, that at times the book becomes a little too poignant to bear. Jim's solitary march to London, to 'see the Lord Mayor' is a case in point, and I suspect that both Masefield and his readers rejoiced when he decided to bring the book to a swift conclusion ... There is no real leavening of 'romance' in the book.Even Jim's protector Marah Gorsuch, though quite an attractive figure, is hardly a trustworthy one:

I had never really liked the man – I had feared him too much to like him – but he had looked after me for so long, and had been, in his rough way, so kind to me, that I cried for him as though he were my only friend.In fact, as I commented in 1984, "Jim Davis ... reads almost like a tract against adventures."

John Masefield: Jim Davis (1911 / 1975)

John Masefield: Jim Davis (1911 / 1975)•

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938 / 1974)

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938 / 1974)It's nice to record that Masefield's penultimate children's book, Dead Ned , written some thirty years later, and subtitled "The Autobiography of a Corpse Who Rediscovered Life Within the Coast of Dead Ned and Came to What Fortune You Shall Hear", is in many ways the most vivid and enthralling of all his many novels.

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938)

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938)His grasp of eighteenth century idiom is far superior to that of subsequent writers such as Leon Garfield or Philip Pullman. It certainly helps to have a poet's sensitivity to language when your material - murder, prison, execution, slave ships - is as melodramatic as this.

There's something of the atmosphere of a nightmare or a fever dream about Ned Mansell's story. It's not so much an escape from the horrors of the late 1930s, as an attempt to see them from a different angle.

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938)

John Masefield: Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse (1938) John Masefield: Dead Ned & Live and Kicking Ned (1938-39)

John Masefield: Dead Ned & Live and Kicking Ned (1938-39)Unfortunately its eagerly awaited sequel, Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned, cannot really sustain the pace and excitement of the original.

The material - a search for a mysterious lost city in the depths of darkest Africa - is as good as ever. Rider Haggard thrived on just such plots. Pierre Benoît's famous (and much filmed) novel L'Atlantide (1919) is a classic piece of French adventure fiction.

John Masefield: Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned (1939 / 1975)

John Masefield: Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned (1939 / 1975)I was a little shocked when I found out that the Puffin edition of the novel had been abridged . It was, admittedly, done by Vivian Garfield (neé Vivian Alcock), Leon Garfield's second wife, and a successful children's author in her own right. When, however, some years later I managed to locate:

a copy of the original novel, I began to understand the motives of the editors at Puffin Books in abridging it. Certainly it read better in its original form, but there was a great deal of unnecessary detail about the bureaucratic infighting in the Lost City, which was threatened by an imminent invasion. Clearly Masefield meant this as satire on the unpreparedness of England for the oncoming Second World War, but it did have the effect of undercutting the realism of the rest of the narrative.I'm not sure that the novel really works very well in either form. There's a lot of great material there, though.

John Masefield: Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned (1939)

John Masefield: Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned (1939)•

John Masefield with his daughter Judith, illustrator of The Box of Delights (1927)

John Masefield with his daughter Judith, illustrator of The Box of Delights (1927)How, then, should one conclude? Eight of Masefield's lifetime total of 23 novels was written for children - that's (roughly) one in three. He was not perhaps so ideally suited to the form as, say, Rudyard Kipling, who found it a good way of communicating his views without the full apparatus of authoritarianism and militarism which pervades so much of his adult fiction.

The Masefield of the children's books is not really that different from the one we meet in the rest of his work - witness the recurrence of many of the themes and characters (Abner Brown, for instance, and the imaginary South American country Santa Barbara) we encounter in The Midnight Folk in earlier novels such as Sard Harker and ODTAA .

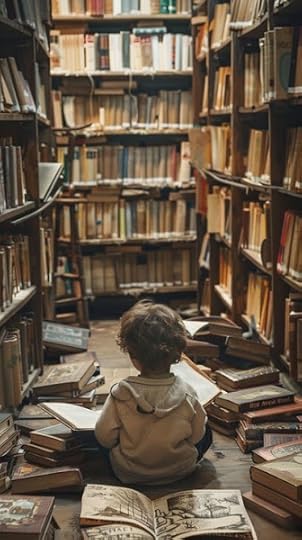

I suspect it's true that the children's books have dated better, though. The genre of the "rattling good yarn", which was one of Masefield's specialities, has now largely been superseded by more brutal and pitiless thrillers. I'm pretty sure that books such as Dead Ned and The Box of Delights, however, will continue to delight imaginative children as long as there are libraries with long dusty sets of shelves to find them in ...

Stockcake: Free Child among Books

Stockcake: Free Child among Books•

John Masefield (1912)

John Masefield (1912)John Edward Masefield

(1878-1967)

Children's Books:

Martin Hyde: The Duke's Messenger (1909)Martin Hyde: The Duke’s Messenger. 1910. Redhill, Surrey: Wells Gardner, Darton and Co. Ltd., 1949. A Book of Discoveries (1910) A Book of Discoveries. Illustrated by R. Gordon Browne. London: Wells, Gardner Darton & Co., 1910. Lost Endeavour (1910)Lost Endeavour. 1910. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, n.d. Jim Davis (1911)Jim Davis. 1911. Illustrated by Mead Schaeffer. London: Wells Gardner, Darton and Co. Ltd., 1924. The Midnight Folk (1927)The Midnight Folk. 1927. Illustrated by Rowland Hilder. World Books Children’s Library. London: The Reprint Society, 1959.The Midnight Folk. 1927. Abridged by Patricia Crampton. 1984. Fontana Lions. London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd., 1985. The Box of Delights: or When the Wolves Were Running (1935)The Box of Delights, or When the Wolves were Running. 1935. Illustrated by Judith Masefield. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1958.The Box of Delights; When The Wolves Were Running. 1935. Illustrated by Faith Jaques. Abridged by Patricia Crampton. 1984. Fontana Lions. London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd., 1984. Dead Ned (1938)Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse Who recovered Life within the Coast of Dead Ned and came to what Fortune you shall hear. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1938.Dead Ned: The Autobiography of a Corpse Who Recovered Life within the Coast of Dead Ned and Came to What Fortune you shall hear. 1938. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. Live and Kicking Ned (1939)Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned. 1939. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1939.Live and Kicking Ned: A Continuation of the Tale of Dead Ned. Abridged by Vivian Garfield. 1939. Puffin Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

Books about King Arthur:

Tristan and Isolt: A Play in Verse (1927)Tristan and Isolt: A Play in Verse. London: William Heinemann, 1927. Midsummer Night and Other Tales in Verse (1928)Included in: The Collected Poems. 1923. Enlarged Edition. 1932. Enlarged Edition. 1938. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1941. Badon Parchments (1947)Badon Parchments. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1947. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield. Ed. David Llewellyn Dodds (1994)Arthurian Poets: John Masefield. Ed. David Llewellyn Dodds. Arthurian Studies, 32. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1994.

•

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)Arthurian Poets Series:

[1990-1996]

Arthurian Poets: Matthew Arnold & William Morris (1990)

Arthurian Poets: Matthew Arnold & William Morris (1990)Arthurian Poets: Matthew Arnold & William Morris. Ed. James P. Carley. Arthurian Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1990.

Arthurian Poets: Edwin Arlington Robinson (1990)

Arthurian Poets: Edwin Arlington Robinson (1990)Arthurian Poets: Edwin Arlington Robinson. Ed. James P. Carley. Arthurian Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1990.

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)

David Llewellyn Dodds, ed. Arthurian Poets: John Masefield (1994)Arthurian Poets: John Masefield. Ed. David Llewellyn Dodds. Arthurian Studies, 32. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1994.

Arthurian Poets: Charles Williams (1995)

Arthurian Poets: Charles Williams (1995)Arthurian Poets: Charles Williams. Ed. David Llewellyn Dodds. Arthurian Studies, 24. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1995.

Arthurian Poets: Algernon Charles Swinburne (1996)

Arthurian Poets: Algernon Charles Swinburne (1996)Arthurian Poets: Algernon Charles Swinburne. Arthurian Studies. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1996.

•

Published on November 16, 2025 14:34

October 31, 2025

Easy Pieces: Reading Popular Books on Science

James Gleick: Genius: Richard Feynman and Modern Physics (1992)

James Gleick: Genius: Richard Feynman and Modern Physics (1992)Science is a way to teach how something gets to be known, what is not known, to what extent things are known (for nothing is known absolutely), how to handle doubt and uncertainty, what the rules of evidence are, how to think about things so that judgments can be made, how to distinguish truth from fraud, and from show. - Richard Feynman [quoted in Genius, p.285]

Perhaps I should say: trying to read popular books on science. They tend to start off quite straightforwardly, then segue into some esoteric explanation of something mathematical, and after that I'm lost ...

But no-one gets anywhere without perseverance. The other day I bought a copy of the book above for a couple of bucks in a Salvation Army shop. I've been reading it ever since with steadily increasing interest. I don't really understand it, mind you. It still isn't quite clear to me exactly what Richard Feynman's "genius" consisted of. There's no obvious manifestation of it to be seen as yet, unlike Einstein's Theory of Relativity or Oppenheimer's atomic bomb. But at times I begin to think that even a scientific illiterate such as myself might be able to glimpse something of his achievements even at second-hand.

Richard Feynman: Six Easy Pieces: The Fundamentals of Physics Explained (1994)

Richard Feynman: Six Easy Pieces: The Fundamentals of Physics Explained (1994)A few years ago, I bought a copy of the book above (also second-hand, in an opportunity shop). The title proved to be a bit of a misnomer, as I can't say I found any of the pieces particularly easy. But, as I recall it, that was also the point of the film Five Easy Pieces - which is presumably what the two editors, Matthew Sands and Robert Leighton, were thinking of when they gave their book of selections from Feynman's introductory lectures that title.

Bob Rafelson, dir.: Five Easy Pieces (1970)

Bob Rafelson, dir.: Five Easy Pieces (1970)•

William Blake: Newton (1795)

William Blake: Newton (1795)John Maynard Keynes ... spoke of Newton as "this strange spirit, who was tempted by the Devil to believe ... that he could reach all the secrets of God and Nature by the pure power of mind - Copernicus and Faustus in one. Why do I call him a magician? Because he looked on the whole universe and all that is in it as a riddle, as a secret which could be read by applying pure thought to certain evidence, certain mystic clues which God had laid about the world to allow a sort of philosopher's treasure hunt to this esoteric brotherhood." - Freeman Dyson [quoted in Genius, p.317]

I suppose that the question I'm asking myself here is a fairly obvious one. Why do I keep on battering my head against the brick wall of books such as these? I clearly lack the background in mathematics - let alone physics - to make sense of them, and yet there's something attractive in the notion that a few ideas, a few precious gleams of knowledge might get through the barrier of my resolutely humanist education and give me a glimpse of what the universe is all about.

Banesh Hoffmann: The Strange Story of the Quantum (1947)

Banesh Hoffmann: The Strange Story of the Quantum (1947)Some of the blame must be laid at the door of Banesh Hoffmann's The Strange Story of the Quantum. There's a tedious habit among us literary folk to try to sum up Einstein's famous theories as something along the lines of "everything is relative" - or (even worse) to make strained analogies between Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle and the perilous lack of convictions underlying modern thought.

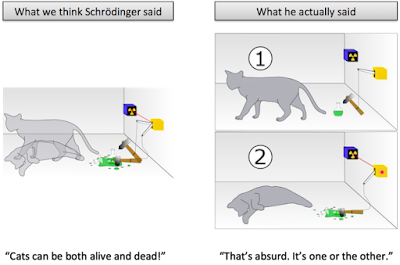

And as for all the stupid things we've said at one time or another about Schrödinger's cat! Don't get me started ...

How We Misunderstood Schrödinger’s Cat

How We Misunderstood Schrödinger’s CatBack in the days before Wikipedia, though, it wasn't so easy to get quick summaries of what such pat formulae really meant. Hoffmann's Strange Story of the Quantum gave me my first real glimpse into how these discoveries had actually been made, without all the clichés. I suppose, in a sense, I've been looking for a sequel as good as that ever since.

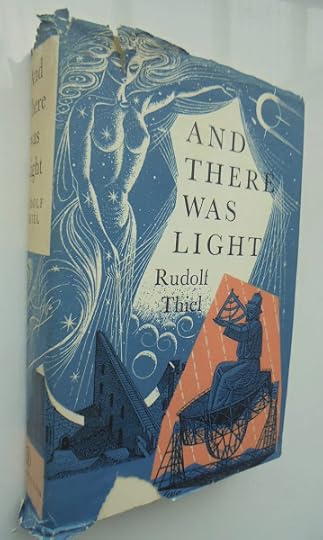

Rudolf Thiel: And There Was Light: The Discovery of the Universe (1958)

Rudolf Thiel: And There Was Light: The Discovery of the Universe (1958)Way before that, though, I encountered a copy of the book above in the Rangitoto College Library. Its admittedly somewhat simplistic account of the history of astronomy fascinated me, and it wasn't long before I found myself reading Arthur Koestler's rather more testing exploration of the same territory, The Sleepwalkers:

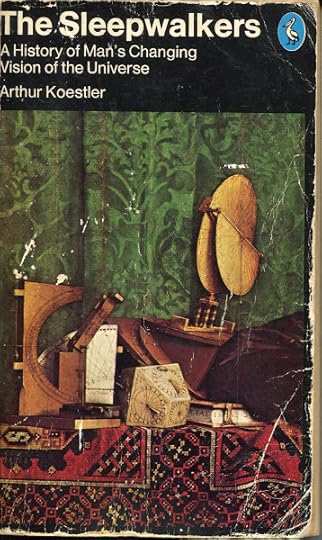

Arthur Koestler: The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe (1958)

Arthur Koestler: The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe (1958)Like most of Koestler's work, it's suffered a bit of an eclipse in recent times. There are certainly many eccentricities in his account of the birth of modern cosmology. His decision to end with Newton, on the rather flimsy pretext that we still inhabit an essentially Newtonian universe, is particularly frustrating.

What's great about the book is its engagé and even, at times, polemic tone. Koestler argues his case passionately, and he makes it clear that sticking to the comfortable concensus of opinion is not an option. He follows the evidence where it leads him - a strong encouragement to his readers to do the same. I've read the book so many times I practically know it by heart, but the lengthy account of his hero Kepler's life and times still gives me a thrill after all these years.

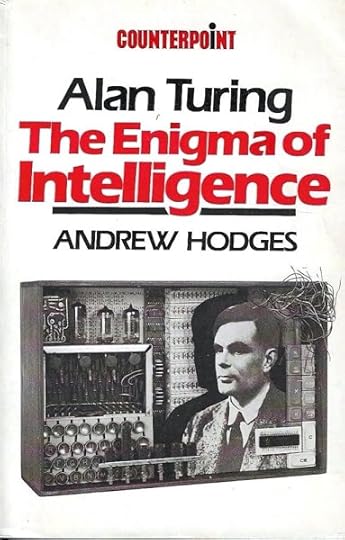

Andrew Hodges: Alan Turing: The Enigma of Intelligence (1958)

Andrew Hodges: Alan Turing: The Enigma of Intelligence (1958)One of the advantages of having been a Sci-fi fan since my early teens is that boffin extraordinaire Alan Turing was well known to me long before the details of his wartime service at Bletchley Park were revealed. The "Turing test" was a frequent subject of discussion in the SF magazines I read, and his vital part in the creation of modern computers was common knowledge to us Sci-fi mavens long before the name "Enigma" ever strayed into print.

And, like everyone else, I stumbled through the pages of Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach with increasing bewilderment - until, that is, I made the reluctant decision to skip the pages of exercises and simply try to follow the text.

Douglas Hofstadter: Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1999)

Douglas Hofstadter: Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1999)•

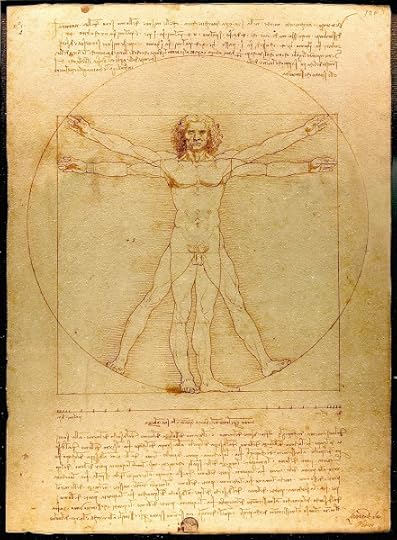

Leonardo da Vinci: Vitruvian Man (c.1490)

Leonardo da Vinci: Vitruvian Man (c.1490)Would I had phrases that are not known, utterances that are strange, in new language that has not been used, free from repetition, not an utterance which has gone stale, which men of old have spoken. - Khakheperressenb, an Ancient Egyptian scribe [quoted in Genius, p.326]

Do I feel better for having read all these books? Not particularly. They mostly just succeeded in underlining for me the gulf between my kind of knowledge and the mathematical, scientific kind.

At least I've ended up knowing a bit more about what I don't know, though. I get enough from them to see the bankruptcy of the simplified explanations we tend to rely on. So in that sense I do feel a bit better educated.

Each one I pick up still gives me a shiver of hope, however. As Liza Minnelli once put it: "Maybe this time ..." In any case, it seems to be enough to keep me filling in these gaps in - at the very least - my knowledge of the history of science.

Minnellian Woman: Cabaret (1972)

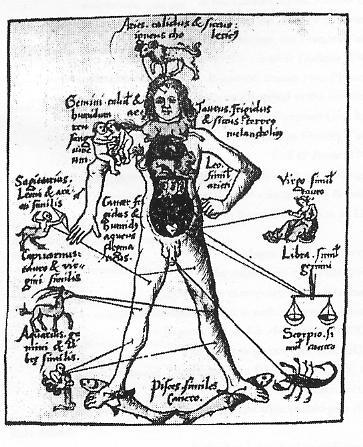

Minnellian Woman: Cabaret (1972)I wonder, too, if any of this fascination has manifested itself in my own work? My first novel, Nights with Giordano Bruno, for instance, concludes with the diagram below - chosen, I suppose, as a kind of distorted mirror-image of Da Vinci's Vitruvian man.

The novel itself is ordered according to a mad numerological scheme, inspired principally by the Memory Palaces described in Frances Yates' classic account The Art of Memory (1966). I suppose that the simultaneous fascination and distrust I feel for such ways of ordering the mind has been influenced also, by all this reading about modern science: its apparently chaotic and arbitrary nature, combined with its inability to find a way out of its dialectic structures, are continually belied by the practical success its towering edifices of thought repeatedly achieve in the (so-called) "real world".

What else can a poor humanist do, under such circumstances, than construct a Don Quixote-like parody of the kinds of rabbit-hole thinking which have become more and more prevalent over the past 25 years?

Jack Ross: Nights with Giordano Bruno (2000)

Jack Ross: Nights with Giordano Bruno (2000)•

NAASP: Stars

NAASP: StarsCosmology, Mathematics & Physics

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600)Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)Albert Einstein (1879-1955)Richard P. Feynman (1918-1988)Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)Stephen Hawking (1942-2018)Douglas R. Hofstadter (1945- )Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)Isaac Newton (1643-1727)J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967)Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937)Alan Turing (1912-1954)Anthologies & Secondary Literature

Filippo [Giordano] Bruno (1548-1600)

Bruno, Giordano. Candelaio. Ed. Giorgio Bárberi Squarotti. Collezione di Teatro, 59. 1964. Torino: Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1981.

[Bruno, Giordano. ‘La Cena de le Ceneri’. 1584. In Opere Italiani. Volume 1: Dialoghi Metafisici. Ed. Giovanni Gentile. 3 vols. 1907-9. Bari: Gius. Laterza & Figli, 1907. 1-126, 415-17. / ‘De Gli Eroici Furori’. 1585. In Opere Italiani. Volume 2: Dialoghi Morali. Ed. Giovanni Gentile. 3 vols. 1907-9. Bari: Gius. Laterza & Figli, 1908. xii-xix, 377, 408, 434. / Firpo, Luigi. Il Proceso di Giordano Bruno. Quaderni della Rivista Storica Italiana, 1. Napoli: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1949. 16-17, 46-51, 54-61, 104-5, 120. / Frigerio, Maurilio. ‘Cronologia.’ In Invito al Pensiero di Giordano Bruno. Milano: Gruppo Ugo Mursia Editore S.p.A, 1991. 5-17.]

Bruno, Giordano. La Cena de le Ceneri: The Ash Wednesday Supper. 1584. Ed. & Trans. Edward A. Gosselin & Lawrence S. Lerner. 1977. Renaissance Society of America Reprint Texts, 4, 59. Toronto: University Of Toronto Press, 1995.

Bossy, John. Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair. 1991. London: Vintage , 1992.

Filippini, Serge. The Man in Flames. 1990. Trans. Liz Nash. Dedalus Europe 1999. Sawtry, Cambs: Dedalus Ltd., 1999.

Fulin, R., ed. Giordano Bruno a Venezia: Documenti inediti tratti dal Veneto Archivio Generale. Nobilissime Nozze: Comello - Totto. Venezia: Tip. Editrice Antonelli, 1864.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)

Gingerich, Owen. The Book Nobody Read: Chasing the Revolutions of Nicolaus Copernicus. 2004. Arrow Books. London: The Random House Group Limited, 2005.

Rosen, Edward, trans. Three Copernican Treatises: The Commentariolus of Copernicus / The Letter against Werner / The Narratio Prima of Rheticus. Second Edition, Revised with an Annotated Copernicus Bibliography, 1939-1958. 1939. New York: Dover Publications, 1959.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

Einstein, Albert. Relativity: The Special and General Theory. A Popular Exposition. 1916. Trans. Robert W. Lawson. 1920. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1977.

Bodanis, David. E = mc2: A Biography of the World's Most Famous Equation. Macmillan. London: Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2000.

Richard Phillips Feynman (1918-1988)

Feynman, Richard P. Six Easy Pieces. 1995. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998.

Gleick, James. Genius: Richard Feynman and Modern Physics. 1992. An Abacus Book. London: Little, Brown and Company (UK), 2000.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

Santillana, Giorgio de. The Crime of Galileo. 1955. Time Reading Program Special Edition. 1962. Alexamdria, Virginia: Time Life Books Inc., 1981.

Sobel, Dava. Galileo’s Daughter: A Drama of Science, Faith and Love. London: Fourth Estate, 1999.

Stephen William Hawking (1942-2018)

Hawking, Stephen. The Illustrated A Brief History of Time: Updated & Expanded Edition. 1988. A Labyrinth Book. London: Bantam Press, 1996.

Hawking, Stephen. Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays. London: Bantam Press, 1993.

Hawking, Jane. Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen. ['Music to Move the Stars, 1999]. Rev. ed. 2007. Richmond, Surrey: Alma Books, 2014.

Douglas Richard Hofstadter (1945- )

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. 1979. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Metamagical Themas: Questing for the Essence of Mind and Pattern. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987.

Hofstadter, Douglas R., & Daniel C. Dennett, ed. The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul. 1981. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

Banville, John. The Revolutions Trilogy: Doctor Copernicus; Kepler; The Newton Letter. 1976, 1981, 1982. Picador. 2000. London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 2001.

Connor, James A. Kepler’s Witch: An Astronomer’s Discovery of Cosmic Order Amid Religious War, Political Intrigue, and the Heresy Trial of His Mother. With Translation Assistance by Petra Sabin Jung. 2004. HarperSanFrancisco. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Introduction by Herbert Butterfield. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1959.

Isaac Newton (1643-1727)

More, Louis Trenchard. Isaac Newton: A Biography, 1642-1727. 1934. New York: Dover Publications, 1962.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967)

Bird, Kai, & Martin J. Sherman. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. 2005. London: Atlantic Books, 2009.

Monk, Ray. Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Jonathan Cape. London: Random House, 2012.

Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937)

Campbell, John. Rutherford: Scientist Supreme. Christchurch: AAS Publications, 1999.

Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954)

Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma of Intelligence. 1983. London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1989.

Anthologies & Secondary Literature

Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by A. Square. Illustrations by the Author. 1884. Classic Science Fiction. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

Casti, John L. Paradigms Lost: Tackling the Unanswered Mysteries of Modern Science. 1989. Avon Books. New York: The Hearst Corporation, 1990.

Crombie, A. C. Augustine to Galileo. Volume 1: Science in the Middle Ages, 5th – 13th Centuries. 1959. A Peregrine Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Crombie, A. C. Augustine to Galileo. Volume 2: Science in the Later Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, 13th – 17th Centuries. 1959. A Peregrine Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Duncan, David Ewing. The Calendar: The 5000-year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens – and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days. London: Fourth Estate, 1998.

Euclid. The Thirteen Books of the Elements / Archimedes. The Works, Including the Method / Apollonius of Perga. On Conic Sections / Nichomachus of Gerga. Introduction to Arithmetic. Trans. Thomas L. Heath, R. Catesby Taliaferro, & Martin L. D’Ooge. 1926 & 1939. Great Books of the Western World, 11. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.

Greene, Brian. The Fabric of the Cosmos. 2004. London: Penguin, 2008.

Hoffmann, Banesh. The Strange Story of the Quantum. 1947. A Pelican Book. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions: 50th Anniversary Edition. 1962. Introductory Essay by Ian Hacking. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Landes, David S. Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World. 1983. Rev. ed. 1998. Viking. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2000.

Popper, Karl R. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. 1934. Trans. by the author with Dr. Julius Feed & Ian Feed. 1959. Mansfield Center, CT: Martino Fine Books, 2014.

Poundstone, William. Prisoner’s Dilemma: John von Neumann, Game Theory, and the Puzzle of the Bomb. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

Ptolemy. The Almagest / Copernicus. On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres / Kepler. Epitome of Copernican Astronomy: IV & V; The Harmonies of the World: V. Trans. R. Catesby Taliaferro, & Charles Glenn Wallis. Great Books of the Western World, 16. Ed. Robert Maynard Hutchins. Chicago: William Benton, Publisher / Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952.

Rucker, Rudy. The Fourth Dimension, and How to Get There. Foreword by Martin Gardner. Illustrations by David Povilaitis. 1985. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

Segrè, Gino. Faust in Copenhagen: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics and the Birth of the Nuclear Age. 2007. Pimlico. London: Random House, 2008.

Singh, Simon. Fermat’s Last Theorem: The Story of a Riddle that Confounded the World’s Greatest Minds for 358 Years. Foreword by John Lynch. 1997. London: Fourth Estate, 2002.

Singh, Simon. Big Bang: The Most Important Scientific Discovery of All Time and Why You Need to Know About It. 2004. London: Harper Perennial, 2005.

Teresi, Dick. Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science - from the Babylonians to the Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

Thiel, Rudolf. And There was Light: The Discovery of the Universe. Trans. Richard & Clara Winston. London: Andre Deutsch, 1958.

•

Erik Desmazières: The Library of Babel (1997)

Erik Desmazières: The Library of Babel (1997)

Published on October 31, 2025 14:28

October 28, 2025

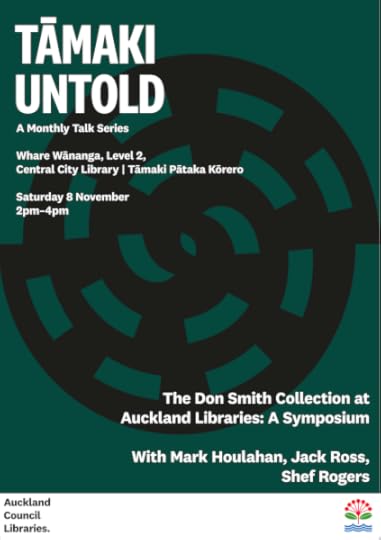

Auckland Central Library Seminar (8/11/25)

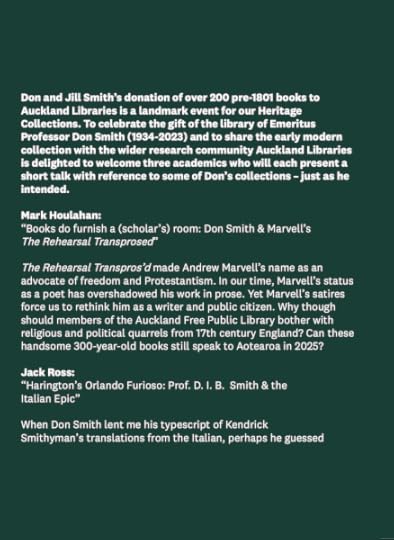

This is just a heads-up to remind any of you who might be interested about the latest in the Central Library's Tāmaki Untold series: a set of short papers designed to celebrate the recent donation of more than 200 pre-1801 books from the collection of my friend and mentor Professor Don Smith to Auckland Libraries earlier this year.

[NB: Previous talks in the series can be accessed at this link].

Here are some more details about Saturday's event:

If you'd like to know more, there's further information available at this link.

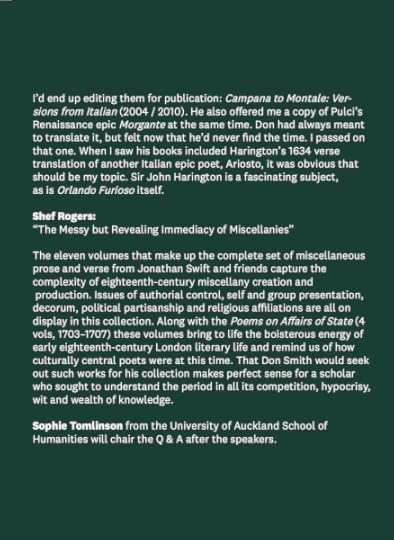

Sir John Harington: Orlando Furioso in English Heroical Verse (1634)

Sir John Harington: Orlando Furioso in English Heroical Verse (1634)•

Jane Wild: l-to-r: Mark Houlahan, Shef Rogers, Jack Ross & Renee Orr (8/11/25)

Jane Wild: l-to-r: Mark Houlahan, Shef Rogers, Jack Ross & Renee Orr (8/11/25)[9/11/25]: Well, the Symposium has now taken place, and - from my point of view, at any rate - seemed to go very well. I found Mark Houlahan's and Shef Roger's papers both amusing and informative. I hope the same was true of my own.

In any case, it was great to see so many old friends there - as well as Don Smith's wife Jill, and his two daughters Penelope and Caitlin.

Here's the text of what I had to say - though I suspect I added a few asides here and there. These will no doubt be available on the podcast recording which the library is planning to release on its Tāmaki Untold site sometime soon.

It remains just to thank the incomparable Jane Wild and her research and special collections team at the Auckland Central Library - Renee Orr, Andrew Henry, Florette Cardon, Ian Snowdon, Annette Keogh and Julian Lubin - for their indispensable help with this event.

•Sir John Harington: Orlando Furioso in English Heroical Verse (1634)

Sir John Harington’s Orlando Furioso:

Prof. D. I. B. Smith & the Italian Epic

Cosa non detta in prosa mai né in rima

When I was asked to speak about one item from Don Smith’s collection, I chose his copy of the revised, 1634 edition of Sir John Harington's 1591 verse translation of Italian poet Lodovico Ariosto’s early sixteenth-century epic Orlando Furioso – "Roland run Mad" might be a good translation of that title.

Why? Partly because I like Ariosto; but also because this, the first full version of his work in English, has its own peculiar interest. Its author, Sir John Harington, was "an English courtier, author and translator, popularly known as the inventor of the flush toilet." Taking that last point first:He was the author of the description of a flush-toilet forerunner ... in A New Discourse of a Stale Subject, called the Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596), a political allegory and coded attack on the monarchy ...The toilet in question, though actually installed in his Kelston house, was used in his book mainly as a metaphor for the "backed-up" nature of business at court: Ajax = A jakes. Get it? Harington was a friend and supporter of the last of Elizabeth I's favourites, the glamorous Earl of Essex, whose failed attempt at a coup d'état against the aging Queen led to a slew of executions in the final years of her reign.

Characteristically, Harington himself escaped any dire consequences by acting as an informant against his former patron. As he put it in his most famous epigram:Treason doth never prosper? What's the reason?Harington first came to court in the 1580s. His poetry and witty conversation earned him immediate favour from the Queen, but he “was inclined to overstep the mark in his somewhat Rabelaisian and occasionally risqué pieces.” When the first sections of his Orlando Furioso began to circulate, the Queen had had enough:

For if it prosper, none dare call it Treason.Angered by the raciness of his translations, Elizabeth told Harington that he was to leave and not return until he had translated the entire poem. She … considered the task so difficult that it was assumed Harington would not bother to comply. Harington, however, chose to follow through with the request and completed the translation in 1591.His later years at the court of King James were less happy. He was (briefly) imprisoned for debt, and even after being pardoned by the King, who made him tutor to the Prince of Wales, Harington failed to prosper. The job came to a premature conclusion when his pupil died of typhoid fever. Harington followed him two weeks later.

He's not an entirely forgotten man, however:Harington appeared as a ghost in an episode of South Park in 2012. He seizes this opportunity to explain how to use his invention, the toilet, properly.I suspect, though, that he would prefer to be remembered for the immense labour involved in translating the lion's share of Orlando Furioso’s 38,736 lines. To give you some standard of comparison, Milton's Paradise Lost contains roughly 10,000 lines – incidentally, Milton copied his famous line "Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhyme" from Ariosto's phrase "cosa non detta in prosa mai, né in rima". Only Spenser's incomplete Faerie Queene (1590-96), clocking in at over 36,000 lines, can rival the sheer scope of Ariosto's masterpiece, first published, in part, in 1516; in full, in 1532.Sir John Harington: Orlando Furioso in English Heroical Verse (1634)

Let's take a look at its opening lines. Here's Ariosto's description of his plans for the poem:Le donne, i cavallier, l'arme, gli amori,Harington has these as:

le cortesie, l'audaci imprese io canto,

che furo al tempo che passaro i Mori

d'Africa il mare, e in Francia nocquer tanto,

seguendo l'ire e i giovenil furori

d'Agramante lor re, che si diè vanto

di vendicar la morte di Troiano

sopra re Carlo imperator romano.Of Dames, of Knights, of armes, of loues delight,Ariosto goes on:

Of courtesies, of high attempts I speake,

Then when ye Moores transported all their might

On Africke seas, the force of France to breake:

Incited by the youthfull heate and spight

Of Agramant their king, that vowd to wreake

The death of King Trayana (lately slaine)

Vpon the Romane Emperour Charlemaine.Dirò d'Orlando in un medesmo trattoHere’s Harington’s version:

cosa non detta in prosa mai, né in rima:

che per amor venne in furore e matto,

d'uom che sì saggio era stimato prima;

se da colei che tal quasi m'ha fatto,

che 'l poco ingegno ad or ad or mi lima,

me ne sarà però tanto concesso,

che mi basti a finir quanto ho promesso.I will no lesse Orlandos acts declare,Compared to Italian, English is a language poor in rhymes. It can be hard for poets not to rhyme in Italian: they spring up naturally as a result of having so many similar endings for their words.

(A tale in prose ne verse yet sung or sayd)

Who fell bestraught with loue, a hap most rare,

To one that earst was counted wise and stayd:

If my sweet Saint that causeth my like care,

My slender muse affoord some gracious ayd,

I make no doubt but I shall haue the skill,

As much as I haue promist to fulfill.

In English, on the other hand, fluent rhyming is desperately difficult to achieve, and those good at it are a breed apart. Ostentatiously clever rhymes tend to sound comic and A. A. Milne-ish, though, unless you're very careful to maintain a formal register.

None of the English versions of Ariosto can really be said to achieve his witty lightness of touch. Probably the closest thing to it in our language would be Byron's Don Juan – and that's more social satire than fantasy. Ben Jonson described Harington’s Orlando Furioso as of " all translations ... the worst" – though unfortunately his host William Drummond, who made a record of the poet's conversation, failed to explain why.

It's true that Harington takes considerable liberties with Ariosto's original text – even here, at the outset of the poem. What, for example, is his justification for transforming the poet's captious mistress (Alessandra Benucci) – referred to in the Italian simply as "colei" [she] – into "my sweet Saint"? Is it possible he intended to invoke Gloriana herself as his muse?

As Jane Everson put it in her 2005 article on Harington's translation:That Harington significantly abbreviated the text of the Orlando furioso is well known; what has not been closely studied is how he does so and the extent to which his modifications are not linguistically but culturally motivated. A close reading reveals changes designed to take account of differing cultural, political, and ideological factors between early sixteenth-century Ferrara and Elizabethan England.Harington’s own justification for this practice was simpler:For my omitting and abreuiating some things, either in matters impertinent to vs, or in some too tedious flatteries of persons that we neuer heard of, if I haue done ill, I craue pardon; for sure I did it for the best … But yet I would not haue any man except, that I should obserue his phrase so strictly as an interpreter, nor the matter so carefully, as if it had bene a storie, in which to varie were as great a sin, as it were simplicitie in this to go word for word.That last sentence seems to invite comparison with translations of Holy Writ, which, by definition, require absolute attentiveness to the meaning and placement of each word.

•

In the section on Ariosto in his 1936 book The Allegory of Love, C. S. Lewis claimed that the ideal happiness he would choose, "if he were regardless of futurity":would be to read the Italian epic – to be always convalescent from some small illness and always seated in a window that overlooked the sea, there to read these poems eight hours of each happy day.Nowadays, when we use the term “Italian Epic”, we tend to mean Dante’s 14th-century masterpiece The Divine Comedy. But that’s not what C. S. Lewis was referring to.

No, for him – and for Sir John Harington and his contemporaries – “Italian epic” meant narrative poets such as Boiardo, Ariosto, and Tasso. And all of them – it’s important to note – appeared in English long before Dante. The first full translation of the Divine Comedy didn’t actually appear until 1785–1802. Henry Cary's, the first to be widely read, didn’t come out till 1814. Nor is it an accident that this coincided with the rise of the Romantic movement.

Mind you, educated English readers were expected to have enough Italian to follow Dante in the original – but then, the same argument would apply to the other poets in the list above. So why did they overshadow him for so long?

Perhaps simply because they’re so much more light-hearted and entertaining. The first major poem in this vein was by Luigi Pulci (1432-1484):an Italian diplomat and poet best known for his Morgante, an epic and parodic poem about a giant who is converted to Christianity by Orlando and follows the knight in many adventures.At one of our last meetings, Don Smith offered me his own two-volume pocket edition of Pulci's Morgante Maggiore. He'd been meaning to translate it himself, he said, but felt that he would never now have the leisure or concentration for the job. And yet it was, he claimed, an essential stepping-stone in the road from Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato to its scene-stealing sequel, Ariosto's Orlando Furioso. And (unlike them) it had never been translated in full into English!

I'm sorry to say that I turned him down. I’d already Englished a few pieces by Petrarch – and those were difficult enough to give me some idea of what a Sisyphean task such a translation would be. I'm glad to announce, though, that the job has finally been completed:In 1983 the Italian-American poet Joseph Tusiani translated in English all 30,080 verses of this work ... [It was] published as a book in 2000.Before that, all that non-Italian-speaking readers had to go on was Byron's 1822 version of Canto One.

Pulci’s contemporary Matteo Maria Boiardo (1440-1494) is best known for his epic poem Orlando innamorato [Orlando in Love]. He grew up in Ferrara, at the court of the d’Este family, who became his patrons.The first translation of Boiardo into English was Robert Tofte's Orlando Inamorato: The Three First Bookes (1598) ...Unfortunately for his posthumous reputation, Boiardo himself fell victim to the Italian vernacular culture wars.Pietro Bembo's reformation of the language in 1525, the rediscovery of Aristotle's Poetics in the 1530s, and the incipient Counter-Reformation in the 1540s all caused [Orlando Innamorato] to fall from favour amongst critics and writers … who found it lacking on linguistic, theoretical, and moral grounds. Gradually, Boiardo's original version was supplanted by Francesco Berni's rifacimento (1542), a recasting of the poem in literary Tuscan ...It wasn't until the nineteenth century that Boiardo's original was rediscovered, and he began to take his proper place as one of the greatest Italian poets of the quattrocento.

It’s a shame, because Ariosto’s poem is a direct sequel to Bioardo’s, and requires at least some knowledge of the former poem for much of the action to make sense: the endless misadventures of Angelica, daughter of the King of the Indies, for instance.

Like its predecessor, Orlando Furioso:describes the adventures of Charlemagne, Orlando, and the Franks as they battle against the Saracens with diversions into many sideplots. [Here, however] The poem is transformed into a satire on the chivalric tradition.It's hard to exaggerate the far-ranging influence of Ariosto's epic. Its satire was far more subtle and subversive than Pulci's slapstick burlesque. The sheer pointlessness of chivalric endeavour was revealed through the endless (often absurd) additions Ariosto made to the original bald outline of Charlemagne's struggle with the Moors of Spain.Sir John Harington: Orlando Furioso in English Heroical Verse (1634)

These include Astolfo's famous journey to the Moon in search of Orlando's lost wits. Assisted by John the Evangelist, who lends him Elijah's fiery chariot for the purpose, Astolfo is astonished to see that the Moon, far from being the perfect, crystalline sphere described by contemporary cosmology, is in fact a kind of rubbish heap for everything lost or mislaid on Earth. He’s nevertheless successful in locating the bottle the mad knight’s wits have been stored in, and manages to induce him to inhale them, thus restoring his equilibrium.

The women in Ariosto’s story, too, are far more proactive than the usual blushing subjects of romance. They include Angelica, the principal heroine, perpetually in flight from one lovelorn swain or another; but also Morgana (the original "fata Morgana") who’s on the point of destroying the world with her enchantments when she is finally defeated by the astute Orlando.

Ariosto himself has been credited with the first use of the term “humanism” – “umanesimo” in Italian. Like most Renaissance thinkers, he saw himself mainly as a rediscoverer of the truths of antiquity: in this case the humanitas of Cicero. The satirical thrust of his creative work, however, invites comparison with Cervantes’s 17th-century novel Don Quixote.

It’s debatable whether the full extent of his iconoclasm was apparent to English readers such as Edmund Spenser, author of his own immensely serious – and, to be honest, somewhat ponderous – epic, The Faerie Queene. Perhaps that’s why Ben Jonson referred to Harington’s Orlando as “of all translations the worst.” The sceptical, worldly Jonson got it. Did Harington? Maybe not.

Unfortunately Ariosto, despite the obvious affinities of his work with the tropes of modern Speculative Fiction, is now little read outside literature classes: the immense length of his poem, and the decline of narrative verse as a medium for storytelling is no doubt largely responsible for this.

However, if you can bring yourself to open the pages of – say – Barbara Reynold’s fluent verse translation of the whole poem, available as a Penguin Classic, I’d say you were in for a treat. Whether the same can be said of Harington’s version is a matter of opinion. The book itself is gorgeous, though, full of notes and illustrations, and closely modelled on the earliest Venetian editions of the original text.Lodovico Ariosto: Orlando Furioso (1587)

[10/8-8/10/25 / 2390 wds]

•

I'll add here any further information or links that come to hand over time:

The full set of plates from Don Smith's copy of the 1634 edition of John Harington's translation are now available here, on the Auckland Council Libraries' Kura: Heritage Collections Online site.A fuller account of my own collection of books on the Italian Epic tradition can be found here, on my bibliography site A Gentle Madness ."Three 'illuminating talks' at the Don Smith Symposium." Auckland library Heritage Trust blog (8/11/25)

•

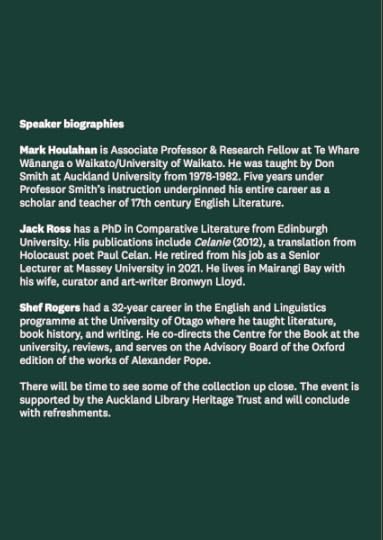

I quattro Poeti Italians (1859)

I quattro Poeti Italians (1859)l-to-r: Dante, Petrarca, Ariosto, Tasso

Published on October 28, 2025 19:21

October 14, 2025

Spooky TV Shows II: How do you prove if ghosts are real?

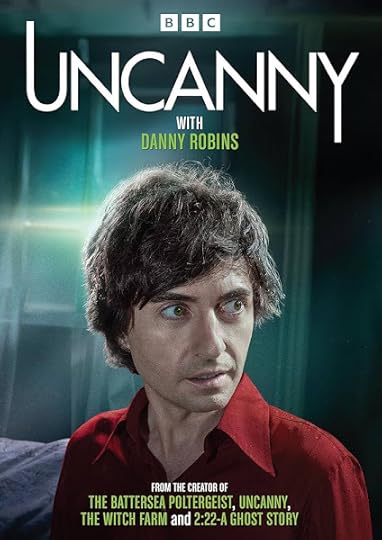

Danny Robins: Uncanny (2023-25)

Danny Robins: Uncanny (2023-25)A few years ago I wrote a kind of round-up of supernatural TV shows past and present, with particular emphasis on the epically silly 28 Days Haunted. It seems that time has come round again. To quote from the film of Shirley Jackson's classic Haunting of Hill House :

No one will hear you, no one will come, in the dark, in the night.Each of the shows I'll be talking about below seems to illustrate a different approach to that age-old conundrum - not so much whether or not ghosts exist, as how best to scare the pants off people by suggesting that they do.

One is British, another American, and the third from Latin America.

James Wan: True Haunting (2025- )

James Wan: True Haunting (2025- )This set of TV shows is a bit different from the last lot, though. Each of them is excellent - in its own, idiosyncratic way. And all of them (even Los Espookys) have interesting points to make about the whole subject of paranormal phenomena.

Julio Torres, Ana Fabrega & Fred Armisen: Los Espookys (2019-22)

Julio Torres, Ana Fabrega & Fred Armisen: Los Espookys (2019-22)At this point, though, I'd better go back to the question in my title: Whether or not you can actually prove the existence of ghosts. If your own answer to that is: You can't - because they don't, then that's the end of the conversation. There's no point in indulging in further debates over the meaning of the word "ghost" - discarnate entities of some sort, or direct proof of life after death? You've made up your mind. You're closed to further discussion.

Danny Glover's show Uncanny - based on his award-winning podcast - gets around this one in a rather ingenious way. He's appointed two teams: "Team Sceptic" - represented by psychologist Dr. Ciarán O'Keeffe; and "Team Believer" - represented by Scottish author and (former) psychology lecturer Evelyn Hollow.

The two are careful not to stray from their preset roles: Ciarán to come up with naturalistic explanations of any odd phenomena; Evelyn to contextualise the events and issues under discussion in the larger field of paranormal lore. And while this certainly makes for interesting, fun TV, it does leave to one side what seems to me the most important conceptual issue raised by such discussions: