Tracy Slater's Blog

November 12, 2025

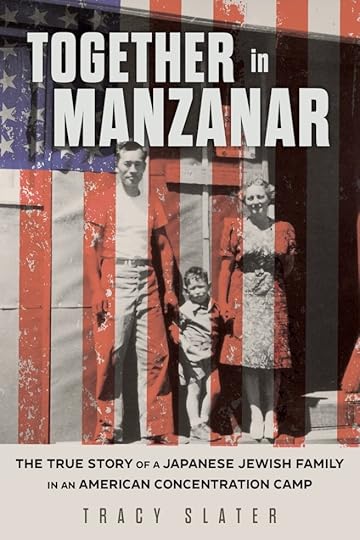

Tracy’s Latest Book

Now that the kiddo is a tween, I’ve been lucky to be able to work on another book. Different topic, but no less close to my heart, given our family’s mixed cultures.

Learn more…

June 28, 2019

Waiting for Baby #2 at 44

Note: I met Bonnie when she emailed me after reading my book, as she was waiting for her second child to be born. She kindly offered to tell us a bit about her experience conceiving naturally in her mid-40s, in the hopes that her story gives hope to women trying for a baby at an older age:

I’ve just turned forty four and for better or for worse, my life is about to change in ways I can’t even begin to imagine. In the next two weeks I’ll have my second child. When my mother was forty four, she drove me, her second child, to college. Let that marinate. I’m starting with child number two at the same age my mom was waving goodbye to her second child. It just puts life into perspective for me, especially since this pregnancy was… unexpected, a medical miracle at forty three. After years of struggling with infertility to have my first child, a little girl, in 2015, we thought we were done. Technically and medically there was nothing wrong with me and my husband, who is four years older than me. We just were just old. Let’s backtrack, I was thirty five when I begrudgingly admitted to myself that I might not meet my soulmate, that I was going to remain single. I told myself that I had a fulfilling life with friends, work, and my family. I took solo vacations, always had interesting jobs, and realized that some people were just meant to be single. And then through a few weeks later through a random website (that my sister secretly signed me up for) I met my future husband. We married when I was thirty eight and began our journey to parenthood as soon as we got back from our honeymoon. If I could go back I would have done things differently. I would have either eloped right away (and avoided that ten month engagement period where I could have been trying) or just gotten off the pill earlier and had big belly in my wedding pictures. I knew thirty eight was on the older end of the age spectrum, but I didn’t realize how much each month really mattered when it came to baby making. I waited six months to see my gynecologist (I’ve since found out that if you’re over thirty five you should only wait three months) and then it took a few months to even get the initial appointment to meet with the highly recommended fertility doctor to get started. She said the best thing I had going for me what that I still had a ‘three’ in my age. I turned thirty nine the next week. After three rounds of IUI (Intrauterine Insemination) we moved on to IVF (In Vitro Fertilization). Again, neither my husband and I had anything wrong with us, just our age. In between the second and third round I somehow got pregnant on my own only to have a miscarriage very early on. The third round worked. We had our baby girl in September of 2015, soon after I turned forty one. Life was great. Easy pregnancy (minus the annoyance of gestational diabetes) and very easy delivery.

My doctor suggested that we not wait longer than six months to start on another baby if that was what we wanted. I knew that as much as my husband loved being a father (something that really shocked him) I knew that there was no way I could convince him to restart the fertility machine a mere six months after becoming parents. So we waited. Fourteen months after our daughter was born we tried IVF again. We were able to implant three embryos, which is high and not the norm, but as my doctor told me later, the lab could already tell that they weren’t looking great. And they weren’t great, none took. We were done. I had finally accepted that I was going to raise an only child, a foreign concept to me, being one of four kids. Growing up I always felt bad for only children, but my husband convinced me that we would be give our daughter the world; the best education, vacations, all our attention, blah blah blah. Just like when I finally accepted that I’d probably be single for life, I got pregnant. Naturally. Shockingly. Like it took my husband weeks, if not months, to really comprehend that we were going to do it again. Especially after our doctor told us that we had such a negligible chance of getting pregnant naturally.

My feelings have been all over the map this pregnancy. A lot of it has to do with my mother passing away very early on in the pregnancy. I told her that I was pregnant on a Monday night and she was admitted to the hospital on Tuesday. The grief and mourning process was pretty unbearable and it didn’t help that I was keeping this very new pregnancy a secret as we didn’t feel confident that it would keep. At the same time my husband and I wanted to finally buy a house. It didn’t seem that daunting to find a nice two or three bedroom in our area, but now we needed more space and we needed it quickly. We’ve since put the house hunt on hold as I can’t imagine moving or even doing the paper work while I can’t even see my feet (or wear any shoes besides flip flops for that matter.) So we’re making it work. It’s been such a whirlwind of emotions. When I expressed my shock that we were really having another baby (at forty four and almost forty eight) I got responses like “but this is what you always wanted!” or “would you rather be going back to a job?” Yes, I always thought I’d want more than one child, but that was before I realized how draining my life would feel with a pretentious two year old who has been going through the Terrible Two’s for OVER A YEAR. And while one of the advantages of having a baby later in life is supposed to be a more patient parent, I find the opposite to be true. When I was younger I probably would have let half the annoying stuff my daughter does roll off my back, but now I feel like every day there’s a new power struggle between us that I usually end up losing. The anxiety I feel about having a second one is mostly due to worrying about the first one. Unlike other moms I’m not worried that I’m not going to love the new baby as much as my first, I’m just worried about keeping my daughter busy when I think I’m going to want to just lay in bed with the new one. It doesn’t help that the baby is coming in the lull of the summer, camp is over and school won’t begin for a few weeks. Will I want my daughter with us at the hospital? Should I take everyone’s offer to watch her so my husband and I can be alone at home with the newborn? I also worry about the stress this is going to add to my always-stressed-out husband. He’s the superhero at our home, he works all week and then is at the beck and call of our daughter ALL weekend (she actually tells me I can leave the room when he’s around.) I feel bad when he tells me that he’s never going to be able to retire. I feel bad that I have to ask someone to run after our daughter when she runs away from us because I’m too large to move and my husband always has a bad knee/back/foot. I feel sad that my kids will experience life with only one grandparent (where I had three of them until my twenties and just lost my dear grandmother last year at forty three.) I wonder if I’ll be a contributing grandmother, if I make it that long. But for now I just need to make it through this month, make it through another healthy delivery, and wait to exhale and start again.

I’m thrilled to report that, since the writing of this piece, Bonnie gave birth to a healthy baby boy, and she and her family of 4 are doing well.

April 10, 2019

Is Hope Ever a Negative?

I get a lot of email from readers of this blog, thanking me for the hope they’ve found in my story of getting pregnant naturally with my first child and giving birth to a healthy baby girl at 46. And I’m moved by and grateful for these messages.

But here’s a question that I can’t stop asking myself when I read messages like this: Is it possible that the hope my story provides could be a negative?

I remember hope feeling like a double-edged sword when I was trying, and failing, month after month to get pregnant. (Until, of course, I beat the odds and did.) I know getting pregnant naturally at 45 and giving birth to a healthy first child at 46 is not the norm, and sometimes I worry I’m giving people the false impression that it happens easily, or can happen for everyone.

In the end, I always come back to the thought that it’s important for people to be reminded that, although it’s relatively rare, it does sometimes happen, and with all the negatives out there that women in their 40s hear all the time, it’s important also to hear some positive stories, too, as long as they are honest.

So that’s I’m trying to do with the posts on this blog about my pregnancy.

Am I right? I go back and forth. Why is hope important to you? In what way is it helpful? Is it hurtful in any ways? I’d love to hear what you think.

January 24, 2019

New Online Group for Mothers 45 and Up

I’ve gotten so many emails and comments on this blog asking me about starting an online group for new mothers at or around 45, or for women who want to feel some of the hope these women’s stories can provide, so here it is!

The group can be found on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/groups/651842948606644/ or by searching under “New Mothers 45 and Up”

Here’s the description:

A group for new mothers, moms-to-be, and the many brave women who are trying to become parents near or after 45 and who want to connect with others who have overcome the odds or are trying to do so. Hopefully, it’s a group that will balance honesty and a nod to the tough statistics facing women trying to conceive at 45; with hope and an acknowledgment that sometimes women do get pregnant after 44 and give birth to the babies they’ve been waiting so long to meet. This group has been inspired by the hundreds of emails I’ve gotten from women who’ve learned that I got pregnant naturally and gave birth to my first and only child, a healthy, fantastic, now-almost-5-year-old, when I was 46. Many of these women have asked me, either in email or on my blog, to start a group like this. I hope it offers support, hope, and community in a world that I know can feel hopeless when trying to conceive a bit later in life.

Please feel free to join us!

March 26, 2018

Mixed Kids, Majority Parents, & the Globally Blended Family

A modified version of this article appeared a while ago in the Wall Street Journal‘s Expat Blog, but I had to cut some important quotes and content, including some advice from interviewees that felt really helpful as a parent in a majority-majority couple raising a mixed child. So here’s the full piece as I originally wrote it:

Perhaps your child, like mine and many others in globally blended families, belongs to the world’s growing mixed population. The World Factbook finds a countable percentage of mixed-ethnicity people in almost a quarter of its 236 countries and territories. Among western nations, England’s and the U.S.’s mixed-race populations are increasing faster than any other minority group.

The “experiences and attitudes” of mixed adults “differ significantly,” finds the Pew Research Center, particularly given race and community context. But one key difference between many children of multinational families and other mixed people has remained largely unmentioned in English-language media and research.

My daughter may be mixed, but she has two biological parents without much clue what it feels like to be a minority as a kid. I’m American, raised with all the cultural privileges afforded to whites in the US, her father is native Japanese, and we live in Greater Tokyo. She is only two, but as she grows she will likely experience joys and struggles shared among many multinational children yet absent from recent conversations about mixed-race kids.

“OUR CHILDREN FACE BULLYING AND EXCLUSION A LOT MORE THAN WE DID.”

Shweta Kulkarni Van Biesen, an Indian expat raising a family in Belgium with her native Belgian husband, expects her kids’ experiences to be “very different…Our children face bullying and exclusion lot more than we did.”

A growing body of English-language research does exist about minority kids with parents bred of majority privilege, although focused largely on transracial adoption of monoracial children and single-parent multiracial families. While these studies may offer important insights for families like Van Biesen’s, their relevance remains limited.

Sharon H Chang, author of the book Raising Mixed Race and the blog Multiracial Asian Families, says the experiences of monoracial minorities and mixed-race people are like “apples and oranges.” “Monoracial people,” she stresses, “have not lived the experience of mixedness, no matter their minority or majority status, and therefore cannot claim to know it.”

Like many mixed-race kids—regardless of how their parents identify—Samuel Ahovi, raised in France by his white mother and Togolese father, says the hardest part was not fitting easily within the ethnic identity of either parent. But their childhood majority-privilege also mattered. “The role of parents,” he says, is to protect “their kids from everyday life obstacles, thanks to their [own] experiences. But being a minority…is something they never had to face as children.”

Chang found similar challenges within Asian-American families. Parents who grew up in Asia, like their white American counterparts, “often lacked a well of critical knowledge to navigate the…difficult webs of U.S. race and racism.” Alternately, parents who were minorities as children “were more likely to have… a critical analysis and tools for resilience” to pass along.

As Ahovi says, his parents “were giving us the best advice they could,” but “discovering it as they were giving it to us.”

“IT AFFECTED US WHETHER THEY WANTED IT TO OR NOT.”

Globe-trotting parents in multinational couples who grow up with majority privilege and then create mixed families may project a particularly problematic blend of tendencies, combining an openness to cultural differences on one hand with a blindness to the way race can play out both within families and throughout a broader community.

Hilary Duff, whose mother grew up in China and white father in Canada, cautions against ignoring ethnicity. “My parents didn’t focus at all on my cultural identity…I suspect this was because they wanted my brother and I to think we would be treated like any other kid. [But] we didn’t look like any other kids, and this affected us whether they wanted it or not.”

IT’S A VERY MIXED BAG.

As with mixed-race people in general, experiences vary widely for children of globally blended couples—particularly given the wide range of races, cultures, and resources among the approximately 232 million people living outside their country of origin, as noted previously in the Wall Street Journal. Mixed-American Nilina Mason-Campbel says, “having a parent of color is…an important resource,” but in cultures like her father’s native Jamaica, black people, although technically majorities, are “secondary in their own country to white people…or those that are light-skinned.”

Others stress not just negatives, but also benefits of growing up multinational, mixed-race, and first-generation minority—another angle parents used to majority privilege might miss. (As I did: When I began this piece, I wondered only about the challenges facing my daughter. I soon realized one of the greatest might involve this slanted preconception.)

British blogger Philip Shigeo Brown recalls, “it was always somehow especially nice to meet other half-English, half-Japanese kids that you could relate to on so many levels, often without anything being said…’Shoes on or off?’ someone might ask. ‘Definitely off!’ everyone always agreed!”

American Eliaichi Sadikiel Kimaro, director of the award-winning documentary on mixed identity A lot Like You, says “race just wasn’t a factor” for her mother growing up in Seoul or her father on Mt Kilimanjaro. Her parents “had blind-spots when it came to race” she explains, “that both helped and hindered my own understanding…of racism’s impact on my life.”

Brown and others see a positive future for mixed children of multinational couples who grew up with majority privilege. “The world is getting smaller and more connected, facilitated hugely by the Internet and social networking,” he says, combatting isolation and forging “communities to talk to, share and learn from.” In a sentiment echoed by Brown and others, Duff urges globally blended parents to “embrace the duality of their child, and…teach them about their background[s]. Even if kids don’t entirely understand,” Duff urges, “they’ll appreciate it later.”

Still, others caution against expecting a one-sized-fits-all answer. Of his experience being an Asian-American child of white parents through adoption, author Matthew Salesses says people often look for universal “steps [to] follow to make everything turn out okay. There aren’t.”

The same may be true for mixed-race kids of many multinational couples. But surely beginning a conversation is a good place to start.

MIXED KIDS, MAJORITY PARENTS, & THE GLOBALLY BLENDED FAMILY

A modified version of this article appeared a while ago in the Wall Street Journal‘s Expat Blog, but I had to cut some important quotes and content, including some advice from interviewees that felt really helpful as a parent in a majority-majority couple raising a mixed child. So here’s the full piece as I originally wrote it:

Perhaps your child, like mine and many others in globally blended families, belongs to the world’s growing mixed population. The World Factbook finds a countable percentage of mixed-ethnicity people in almost a quarter of its 236 countries and territories. Among western nations, England’s and the U.S.’s mixed-race populations are increasing faster than any other minority group.

The “experiences and attitudes” of mixed adults “differ significantly,” finds the Pew Research Center, particularly given race and community context. But one key difference between many children of multinational families and other mixed people has remained largely unmentioned in English-language media and research.

My daughter may be mixed, but she has two biological parents without much clue what it feels like to be a minority as a kid. I’m American, raised with all the cultural privileges afforded to whites in the US, her father is native Japanese, and we live in Greater Tokyo. She is only two, but as she grows she will likely experience joys and struggles shared among many multinational children yet absent from recent conversations about mixed-race kids.

“OUR CHILDREN FACE BULLYING AND EXCLUSION A LOT MORE THAN WE DID.”

Shweta Kulkarni Van Biesen, an Indian expat raising a family in Belgium with her native Belgian husband, expects her kids’ experiences to be “very different…Our children face bullying and exclusion lot more than we did.”

A growing body of English-language research does exist about minority kids with parents bred of majority privilege, although focused largely on transracial adoption of monoracial children and single-parent multiracial families. While these studies may offer important insights for families like Van Biesen’s, their relevance remains limited.

Sharon H Chang, author of the book Raising Mixed Race and the blog Multiracial Asian Families, says the experiences of monoracial minorities and mixed-race people are like “apples and oranges.” “Monoracial people,” she stresses, “have not lived the experience of mixedness, no matter their minority or majority status, and therefore cannot claim to know it.”

Like many mixed-race kids—regardless of how their parents identify—Samuel Ahovi, raised in France by his white mother and Togolese father, says the hardest part was not fitting easily within the ethnic identity of either parent. But their childhood majority-privilege also mattered. “The role of parents,” he says, is to protect “their kids from everyday life obstacles, thanks to their [own] experiences. But being a minority…is something they never had to face as children.”

Chang found similar challenges within Asian-American families. Parents who grew up in Asia, like their white American counterparts, “often lacked a well of critical knowledge to navigate the…difficult webs of U.S. race and racism.” Alternately, parents who were minorities as children “were more likely to have… a critical analysis and tools for resilience” to pass along.

As Ahovi says, his parents “were giving us the best advice they could,” but “discovering it as they were giving it to us.”

“IT AFFECTED US WHETHER THEY WANTED IT TO OR NOT.”

Globe-trotting parents in multinational couples who grow up with majority privilege and then create mixed families may project a particularly problematic blend of tendencies, combining an openness to cultural differences on one hand with a blindness to the way race can play out both within families and throughout a broader community.

Hilary Duff, whose mother grew up in China and white father in Canada, cautions against ignoring ethnicity. “My parents didn’t focus at all on my cultural identity…I suspect this was because they wanted my brother and I to think we would be treated like any other kid. [But] we didn’t look like any other kids, and this affected us whether they wanted it or not.”

IT’S A VERY MIXED BAG.

As with mixed-race people in general, experiences vary widely for children of globally blended couples—particularly given the wide range of races, cultures, and resources among the approximately 232 million people living outside their country of origin, as noted previously on this blog. Mixed-American Nilina Mason-Campbel says, “having a parent of color is…an important resource,” but in cultures like her father’s native Jamaica, black people, although technically majorities, are “secondary in their own country to white people…or those that are light-skinned.”

Others stress not just negatives, but also benefits of growing up multinational, mixed-race, and first-generation minority—another angle parents used to majority privilege might miss. (As I did: when I began this piece, I wondered only about the challenges facing my daughter. I soon realized one of the greatest might involve this slanted preconception.)

British blogger Philip Shigeo Brown recalls, “it was always somehow especially nice to meet other half-English, half-Japanese kids that you could relate to on so many levels, often without anything being said…’Shoes on or off?’ someone might ask. ‘Definitely off!’ everyone always agreed!”

American Eliaichi Sadikiel Kimaro, director of the award-winning documentary on mixed identity A lot Like You, says “race just wasn’t a factor” for her mother growing up in Seoul or her father on Mt Kilimanjaro. Her parents “had blind-spots when it came to race” she explains, “that both helped and hindered my own understanding…of racism’s impact on my life.”

Brown and others see a positive future for mixed children of multinational couples who grew up with majority privilege. “The world is getting smaller and more connected, facilitated hugely by the Internet and social networking,” he says, combatting isolation and forging “communities to talk to, share and learn from.” In a sentiment echoed by Brown and others, Duff urges globally blended parents to “embrace the duality of their child, and…teach them about their background[s]. Even if kids don’t entirely understand,” Duff urges, “they’ll appreciate it later.”

Still, others caution against expecting a one-sized-fits-all answer. Of his experience being an Asian-American child of white parents through adoption, author Matthew Salesses says people often look for universal “steps [to] follow to make everything turn out okay. There aren’t.”

The same may be true for mixed-race kids of many multinational couples. But surely beginning a conversation is a good place to start.

January 31, 2018

How Did You Know It Was Time To Stop?

I’ve been lucky to get over 500 personal emails from women who’ve visited this blog, women who’ve generously shared their stories and their hopes–and frequently their sadness–with me. Many have also asked me the same question: when did I know, or how did I decide, it was time to stop fertility treatments?

In my book, I wrote about how I dealt with this question. I also wrote about how it felt to mourn the child I believed I’d never meet, a strange mourning of missing what I never had, after spending almost everything I had inside me trying to achieve it. (If you’ve seen other posts on this blog, you’ll know that this was all before I became pregnant naturally at 45 and a half and delivered a healthy baby girl after I turned 46.)

For those of you struggling with this question now, I’m happy to offer here the part of the book where I write about all of this, in the hopes that, like so much of what’s already on this blog, it helps you feel less alone.

“For God’s sake, you’re not going to get pregnant, Tracy,” my mother—never one to mince words—tried to level with me a few months later over Skype. She worried we were wasting precious time. Toru and I had stopped the IVF treatments, but I insisted we still try every month with ultrasounds and hormone support from the clinic, plus new twice-a-day injections of a blood thinner for a “clotting disorder” the clinic had diagnosed, which they claimed could cause early-state miscarriage. My stomach bloomed with red and purple welts, but I was undeterred.

My eldest sister said she cried for me, she was so sad that I wouldn’t have a child with Toru, but she also couldn’t understand why we didn’t “just adopt.” “I mean,” she said, “If you’re still not willing to do egg donation.” Both she and my mother pointed out that with adoption too, we might need to hurry, since many agencies had age cutoffs.

****

“A therapist once told me,” one woman wrote on my Over-40 online TTC forum, “that if what I wanted most in the world was to be a mother, then I would be one; I would find a way, no matter what.” The writer found deep comfort in this truth, and when I read her post, I admired her, but I knew that wasn’t true for me.

What I wanted most in the world was to be with Toru, and then to have his biological child.

When Toru had told me years before that he wasn’t open to either egg donation or adoption, I felt an unexpected sense of relief. Since adoption in Japan is so rare, I wasn’t surprised by his stance. But as we’d begun the process of trying to have a baby years before, I’d realized that my growing longing to parent our biological child didn’t necessarily translate into a yearning to be a parent in general.

By now, the experience of going through years of treatments had confirmed another surprising truth to me: just because we think we are open to certain possibilities in the abstract—like adoption—we never know where our true limits lie until we are faced with actual, lasting choices. Rational or not, I felt safest in my gut with the idea of a baby who was half Toru. I believed it would be harder for me not to bond with, not to love a child whose every cell contained half of him. And if Toru and I couldn’t make a baby together, I’d still rather be together and childless than a mother apart from him.

In any case, with my forty-fifth birthday now looming just past summer, the whole issue would become obsolete soon. We’d agreed we’d stop all medical treatment when I passed that milestone. Most fertility studies don’t even consider women giving birth at forty-five or beyond, when the average chance of a someone having a baby with her own eggs drop below one percent. The most recent U.S. National Health Statistics report’s definition of a woman of child-bearing age: one between fifteen and forty-four. I’d entered the territory of a statistical non-entity.

****

A few months later, I lay curled in bed past midnight, sobs shaking through my body. Toru lay beside me, wiping strands of wet hair from my cheeks. “You know,” he said, his steady eyes locking into place my teary ones, “If we can have baby, that would be like miracle,” he said. “But it will still only be like dessert, because you will always be main course.”

I couldn’t believe we weren’t ever going to meet our baby. It seemed both so obvious and so inconceivable. Another paradox I felt deeply carved into my body but still couldn’t quite wrap my head around: how I could mourn something I’d never even had, how to grieve the loss of something that had never actually existed. The tension between my fear of parenthood and my longing to have Toru’s baby began to transmute now into a kind of weird emotional torsion, a swirl of missing and nothingness, numbness and nostalgia.

But as my birthday came and went, I reminded myself of my enduring good luck in other ways, and I knew it was crucial to remember such a fact. The previous January, Toru and I had celebrated our fifth year of marriage, and we’d laughed when we remembered my original “three-year nuptial plan,” long forgotten once I’d gotten over my initial nerves. The night of our anniversary, sitting at our favorite Italian wine bar, bubbles rising in clear flutes, we’d toasted each other, and then Toru had turned momentarily serious. “Thank you for marrying with me these five years,” he’d said, and once again I couldn’t believe my luck that somehow we had found each other across cultures, continents, and half the world’s wide curve. I’d already gotten my most important wish: to be a family, with Toru.

I thought back to him telling me we were “together in always.” I had no idea where I was in my life, how I would start rebuilding after fixing my existence on a dream that now seemed dead, how I would emerge from the limbo of the past four years. But I realized finally that those years wouldn’t be wasted—and I wouldn’t even choose to do them differently, now that I knew their outcome—because they would stay a testament of our love for our baby, even if we never got to meet that baby. It was a testament that felt precious to me, despite the failures that accompanied it. Really, there was no better place to be, I knew, despite the sadness in my chest, than together where we’d been, and now where I was still, with Toru in always.

Excerpted from the book The Good Shufu: Finding Love, Self, and Home on the Far Side of the World (Putnam, 2015), by Tracy Slater.

The fastest way to get in touch with Tracy is here.

September 20, 2017

Why It’s Not So Rare to Get Pregnant after 45

Hope for Older Women Trying for Healthy Babies

Current conversations about fertility are failing the millions of women around the world who are 40 or over and trying to get pregnant. When we talk about when women should get serious about trying to conceive or of how much fertility declines with age, we talk past a huge community of women who are hoping to become mothers after age 40.

I remember the recurrent sorrow and crazy-making frustration of trying to get pregnant, starting when I was first ready to become a mother—not until I was 41—and lasting until I was lucky enough to conceive my first child at age 45. She was born when I was 46 and she is, I’m incredibly grateful to report, now a healthy, happy 3 and a half year old. I also remember how unhelpful much of the discussion around fertility and age was, during those years when I was trying and failing to get pregnant or to carry a pregnancy to term.

Because here’s the thing: Women like these, and like I once was, are not in the position of deciding when to have a baby or whether they should try before reaching “advanced” or “very advanced maternal age.” The ship has sailed on that one. The reality is, they are already in their 40s. And the teeth-aching desire to meet and hold their baby has not declined with age.

But I’ve realized recently that, surprisingly, the most relevant—and it turns out, most hopeful—information for my fellow 40+ year olds isn’t even found where people tend to look during discussions of fertility. Instead of focusing on studies comparing fertility at various ages or surveys of ART successes and failures, we should look to US census data on births and, perhaps paradoxically, to statistics on abortion, menopause, and sterility.

To be clear: I’m not arguing women should wait. I’m not arguing they shouldn’t. I’m saying, is that if a woman happens to be in her 40s and trying to conceive, she should know there actually is some hope, tempered though it may be. The chances are certainly smaller than when she was 25, and even 35. But that’s immaterial now. And it doesn’t by any stretch mean there is no chance. This point bears stressing and examining in the absence of comparisons with younger women.

Besides having given birth to a healthy baby conceive naturally when I was 45, I’ve also been unusually lucky to have heard from over 500 women, aged 40+ who are trying to conceive or who are already pregnant and who have found me through this blog and left comments here or contacted me directly. I love hearing from all of you and am grateful to be privy to some of the uncensored thoughts, concerns, questions, and emotions being shared among this population.

Especially for those women 42 and older who get in touch, I hear frequently that they’ve either heard or just feel they have “no chance,” a “0%” likelihood of becoming mothers with their own eggs. A significant number also tell me they feel ashamed, have been told they’re “crazy” for thinking they might have a shot. These are the women I’m writing this for now. (And you go, ladies, for trying!)

Overlooked Stats Show Hope for Women 40+

Census statistics on live births & medical abortions

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/report002.pdf: According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2016, there were 111,848 births, (1.1% of population) to women 40-44. This covers all births, not just births to women who were trying to conceive, suggesting that if all 40-44 year olds in 2016 tried to conceive every month, the percentage of women in this age group who’d had babies would be considerably higher. To women between 45-54 (with the great majority falling between 45-49), 9,025 babies were born.

Combining these stats with those on abortion in 2015 for the 40-44 age group, (20,962)–the latest age group and last year in which statistics were collected–and then dividing this number by 3 (accounting for expected 33% miscarriage rate in this age group), we could expect to add around 7,000 babies, totaling close to 120,000 births. This number would actually be a low estimate, since many miscarriages occur before scheduled abortion dates.

All together, we could expect between 125,000-130,000 live births in 2016 to women 40-49. Put into context, that’s a population of babies likely greater than the total population of most of our hometowns.

Perhaps most significantly, these statistics hold steady or decline only somewhat when viewing births before egg donation was available in the US (See births 1933-1998 @ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/natality/mage33tr.pdf.)

Sterility & menopause

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12268772: According to a review of the literature pertaining to declining fertility with age, the likelihood of permanent sterility at age 40 is about 40% and at age 45 is about 80%, meaning one of out every five 45 year olds should be able to become pregnant at some point during their 45th year.

http://www.healthline.com/health/menopause/pregnancy#1: As explained by executive director emeritus of the North American Menopause Society Dr. Marjory Gass, pregnancy even in the mid-to-late 40s is not impossible for most women. “Never assume, ‘Oh, I’m too old to get pregnant,’” Gass has said. “Unless you have gone a year without a period–the technical definition of menopause—pregnancy remains a possibility.”

Birth defects & miscarriage

I get a lot of questions over email and on this blog about whether getting pregnant in the 40s, especially in the mid-40s, guarantees a miscarriage or a child with a genetic abnormality. Many women, myself included, field questions from family members about whether it’s even wise to get pregnant or hope for a positive outcome given the dire statistics on Downs, etc., for older mothers.

When viewed from the perspective of high the risks are compared to pregnancy at 25, the numbers do look grim. But when viewed from the perspective solely of the chances for a healthy baby at various ages throughout the 40s, the numbers are much more hopeful (and again, relevant):

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1071156/: “For women at 42 years of age, more than half of the intended pregnancies (54.5%) resulted in fetal loss…The risk of spontaneous abortion [was] 84.1% by the age of 48 years or older.” So yes, these are scary statistics, and they aren’t great, but they are better than many people fear and assume, especially if we look at them in reverse, from the perspective of a positive outcome rather than negative: a 45% chance of success for a 42-year old to carry a pregnancy to term, and even a 15% chance of success for a 48-year old.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6455611 & https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Genetic_risk_maternal_age : The estimated rate of all clinically significant cytogenetic abnormalities at age 40 is 15.8 per 1000, meaning we can expect between 98-99% of all babies will be born genetically healthy. For age 45, it’s 53.7 per 1000, or between 94-95% of babies. Even for women giving birth at 49, only 12.5% of babies will carry a genetic abnormality, meaning 87 out of every hundred babies will be born genetically average.

So if you’re out there now and are trying to conceive in your 40s, please know that I’ll be keeping you in my thoughts and hoping you have the same good luck I—and almost 9,000 other women aged 45-49 in the U.S. last year—had. And please know that I and thousands of other women are out there, pulling for you.

The fastest way to get in touch with Tracy is here.

(Note: For more about trying to get pregnant, you can also see An Honest Take at Getting Pregnant Naturally at 45, Getting Through to Getting Pregnant at 45 and On Delivering My First Child at 46, other blog posts I wrote in the hopes of supporting people slogging through infertility, although some of the content from these is reproduced in this post. I’ve also gotten quite a few questions about my pregnancy and birth experience, and I’ve written a bit more about those in the Washington Postonline and in Brain, Child Magazine online — although please note that the picture in this latter article is not my daughter! It’s a stock photo the magazine used. In any case, I will continue to keep you all in my thoughts. Finally, if you’re *still* interested in my story [bless you for your patience if so!], the story of how I met and fell in love with my husband–a bit late in life– and then went through years of IVF and finally got pregnant naturally, is in my book The Good Shufu.)

Hidden Hope in Fertility Stats for Women 40+

Current conversations about fertility are failing the millions of women around the world who are 40 or over and trying to get pregnant. When we talk about when women should get serious about trying to conceive or of how much fertility declines with age, we talk past a huge community of women who are hoping to become mothers after age 40.

I remember the recurrent sorrow and crazy-making frustration of trying to get pregnant, starting when I was first ready to become a mother—not until I was 41—and lasting until I was lucky enough to conceive my first child at age 45. She was born when I was 46 and she is, I’m incredibly grateful to report, now a healthy, happy 3 and a half year old. I also remember how unhelpful much of the discussion around fertility and age was, during those years when I was trying and failing to get pregnant or to carry a pregnancy to term.

Because here’s the thing: Women like these, and like I once was, are not in the position of deciding when to have a baby or whether they should try before reaching “advanced” or “very advanced maternal age.” The ship has sailed on that one. The reality is, they are already in their 40s. And the teeth-aching desire to meet and hold their baby has not declined with age.

But I’ve realized recently that, surprisingly, the most relevant—and it turns out, most hopeful—information for my fellow 40+ year olds isn’t even found where people tend to look during discussions of fertility. Instead of focusing on studies comparing fertility at various ages or surveys of ART successes and failures, we should look to US census data on births and, perhaps paradoxically, to statistics on abortion, menopause, and sterility.

To be clear: I’m not arguing women should wait. I’m not arguing they shouldn’t. I’m saying, is that if a woman happens to be in her 40s and trying to conceive, she should know there actually is some hope, tempered though it may be. The chances are certainly smaller than when she was 25, and even 35. But that’s immaterial now. And it doesn’t by any stretch mean there is no chance. This point bears stressing and examining in the absence of comparisons with younger women.

Besides having given birth to a healthy baby conceive naturally when I was 45, I’ve also been unusually lucky to have heard from over 500 women, aged 40+ who are trying to conceive or who are already pregnant and who have found me through this blog and left comments here or contacted me directly. I love hearing from all of you and am grateful to be privy to some of the uncensored thoughts, concerns, questions, and emotions being shared among this population.

Especially for those women 42 and older who get in touch, I hear frequently that they’ve either heard or just feel they have “no chance,” a “0%” likelihood of becoming mothers with their own eggs. A significant number also tell me they feel ashamed, have been told they’re “crazy” for thinking they might have a shot. These are the women I’m writing this for now. (And you go, ladies, for trying!)

Overlooked Stats Show Hope for Women 40+

Census statistics on live births & medical abortions

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_03.pdf: According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2015, there were 111,611 births, (1.1% of population) to women 40-44. This covers all births, not just births to women who were trying to conceive, suggesting that if all 40-44 year olds in 2015 tried to conceive every month, the percentage of women in this age group who’d had babies would be considerably higher. To women between 45-54 (with the great majority falling between 45-49), 8,827 babies were born.

Combining these stats with those on abortion in the 40-44 age group, (20,962), the latest age group for whom statistics were collected, and then dividing this number by 3 (accounting for expected 33% miscarriage rate), we could expect to add almost 7,000 babies, totaling close to 120,000 births. This number would actually be a low estimate, since many miscarriages occur before scheduled abortion dates.

All together, we could expect between 125,000-130,000 live births in 2015 to women 40-49. Put into context, that’s a population of babies likely greater than the total population of most of our hometowns.

Perhaps most significantly, these statistics hold steady or decline only somewhat when viewing births before egg donation was available in the US (See births 1933-1998 @ https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/natality/mage33tr.pdf.)

Sterility & menopause

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12268772: According to a review of the literature pertaining to declining fertility with age, the likelihood of permanent sterility at age 40 is about 40% and at age 45 is about 80%, meaning one of out every five 45 year olds should be able to become pregnant at some point during their 45th year.

http://www.healthline.com/health/menopause/pregnancy#1: As explained by executive director emeritus of the North American Menopause Society Dr. Marjory Gass, pregnancy even in the mid-to-late 40s is not impossible for most women. “Never assume, ‘Oh, I’m too old to get pregnant,’” Gass has said. “Unless you have gone a year without a period–the technical definition of menopause—pregnancy remains a possibility.”

Birth defects & miscarriage

I get a lot of questions over email and on this blog about whether getting pregnant in the 40s, especially in the mid-40s, guarantees a miscarriage or a child with a genetic abnormality. Many women, myself included, field questions from family members about whether it’s even wise to get pregnant or hope for a positive outcome given the dire statistics on Downs, etc., for older mothers.

When viewed from the perspective of high the risks are compared to pregnancy at 25, the numbers do look grim. But when viewed from the perspective solely of the chances for a healthy baby at various ages throughout the 40s, the numbers are much more hopeful (and again, relevant):

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1071156/: “For women at 42 years of age, more than half of the intended pregnancies (54.5%) resulted in fetal loss…The risk of spontaneous abortion [was] 84.1% by the age of 48 years or older.” So yes, these are scary statistics, and they aren’t great, but they are better than many people fear and assume, especially if we look at them in reverse, from the perspective of a positive outcome rather than negative: a 45% chance of success for a 42-year old to carry a pregnancy to term, and even a 15% chance of success for a 48-year old.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6455611 & https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Genetic_risk_maternal_age : The estimated rate of all clinically significant cytogenetic abnormalities at age 40 is 15.8 per 1000, meaning we can expect between 98-99% of all babies will be born genetically healthy. For age 45, it’s 53.7 per 1000, or between 94-95% of babies. Even for women giving birth at 49, only 12.5% of babies will carry a genetic abnormality, meaning 87 out of every hundred babies will be born genetically average.

So if you’re out there now and are trying to conceive in your 40s, please know that I’ll be keeping you in my thoughts and hoping you have the same good luck I—and almost 9,000 other women aged 45-49 in the U.S. last year—had. And please know that I and thousands of other women are out there, pulling for you.

The fastest way to get in touch with Tracy is here.

(Note: For more about trying to get pregnant, you can also see An Honest Take at Getting Pregnant Naturally at 45, Getting Through to Getting Pregnant at 45 and On Delivering My First Child at 46, other blog posts I wrote in the hopes of supporting people slogging through infertility, although some of the content from these is reproduced in this post. I’ve also gotten quite a few questions about my pregnancy and birth experience, and I’ve written a bit more about those in the Washington Postonline and in Brain, Child Magazine online — although please note that the picture in this latter article is not my daughter! It’s a stock photo the magazine used. In any case, I will continue to keep you all in my thoughts. Finally, if you’re *still* interested in my story [bless you for your patience if so!], the story of how I met and fell in love with my husband–a bit late in life– and then went through years of IVF and finally got pregnant naturally, is in my book The Good Shufu.)

January 29, 2017

MIXED KIDS, MAJORITY PARENTS, & THE GLOBALLY BLENDED FAMILY

I recently learned that the Wall Street Journal‘s Expat Blog has ceased offering new content or publishing their existing content for free. I wrote a piece for them last year about raising mixed kids in global families, with the intention that it would remain accessible and free, so here it is in its entirety (with the title they gave it):

‘Blind Spots’ and Other Problems in Globally Blended Families

When the parents are in the majority and the kids are in the minority

By Tracy Slater

Perhaps your child, like mine and many others in globally blended families, belongs to the world’s growing mixed-ethnicity population. The World Factbook finds a countable percentage of mixed-ethnicity people in almost a quarter of its 236 countries and territories. Among western nations, England’s and the U.S.’s mixed-race populations are increasing faster than any other minority group.

Mixed-ethnic children often face very different experiences than their parents, a point stressed by many studies tracking this population’s growth. But within multinational families, there is a unique generation gap. My daughter may be mixed, but she has two biological parents without much clue about what it feels like to be a minority as a kid. I’m a Jewish American, raised with all the cultural privileges afforded to whites in the U.S., her father is native Japanese, and we live in Japan. She is only two, but as she grows she will likely experience the joys and struggles shared among many children in global families—yet absent from recent conversations about mixed-race kids.

There is a growing body of English-language research about minority kids with parents who grew up in the majority, although much of it focuses on transracial adoption of monoracial children. Sharon H. Chang, author of the book “Raising Mixed Race,” cautions against applying this research to families like mine. The experiences of monoracial minorities and mixed-race people, she explained by email, are like “apples and oranges. Monoracial people have not lived the experience of mixedness, no matter their minority or majority status.

Moreover, globe-trotting, multicultural couples who grew up in the majority and give birth to mixed-race children may show a particularly complex set of tendencies, combining an openness to cultural differences and an understanding of how it feels as an adult to stand apart from the norm, with a blindness to the way race can play out within families and the broader community, particularly for children. They are frequently aware of racism as a concept, but many still lack a deeper understanding of its felt truth during a child’s formative years.

American Eliaichi Sadikiel Kimaro, director of the award-winning documentary on mixed identity A lot Like You, said “race just wasn’t a factor” for her mother growing up in Seoul or her father in Tanzania before they moved to the U.S. as adults. “My parents infused me with the belief that I had to work harder, over-achieve and out-perform my white counterparts in order to be seen as equal,” she explained by email. But they also had “blind-spots when it came to race” that limited her own “understanding of the reality, the truth” of how racism would impact and shape her life.

Samuel Ahovi, raised in France by his white mother and Togolese father, said by email that the hardest part of growing up mixed was not fitting easily within the ethnic identity of either parent. But he admitted that the majority-minority generation gap also mattered. Both Ahovi and Hilary Duff, whose mother grew up in China and white father in Canada, said that parents in global families should be careful not to ignore ethnic differences. “My parents didn’t focus at all on my cultural identity. I suspect this was because they wanted my brother and I to think we would be treated like any other kid,” Ms. Duff said by email. But “we didn’t look like any other kids, and this affected us whether they wanted it or not.”

For Mr. Ahovi, the biggest regret involves his inability to speak Ewe, the Togolese language. “I think parents should work hard on transmitting their own culture to their children,” he said. “Maybe if I was able to speak Ewe, if I were at ease with Togolese culture, I could be assimilated as an African, and finally feel 100% part of something.” Ms. Duff urged globally blended parents to “embrace the duality of their child,” and teach them about their background. “Even if kids don’t entirely understand, they’ll appreciate it later.”

Not everyone agrees that the majority-minority generation gap matters in multinational families, although race plays an important factor here, too. According to mixed-race American Nilina Mason-Campbell, in her father’s native Jamaica, black people are both in the majority and “secondary in their own country” to white and light-skinned people. “I haven’t personally seen a connection between whether a parent was raised as a minority or not making a difference,” she said in an email.

Despite these differences, most stress the benefits growing up multinational, mixed-race, and first-generation minority. For British blogger Philip Shigeo Brown, even as a child, “it was always somehow especially nice to meet other half-English, half-Japanese kids that you could relate to on so many levels, often without anything being said,” he wrote in an email. For instance, someone might ask, “’Shoes on or off? ‘Definitely off!’ everyone always agreed!”

According to Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, a Stanford University psychologist and author of the book When Half is Whole, his mixed heritage—from his Japanese mother and Irish-American father—has provided lasting positive impact despite the “sense of isolation” he said in an email he experienced occasionally when young. As he wrote in an article for Psychology Today, “I tolerate inconsistency and dissonance rather than trying to resolve differences and needing to decide which way is right and which is wrong. I embrace complexity and ambiguity, balancing these diverse and even seemingly conflicting culturally learned perspectives.”

Overall, mixed-race children of multinational couples said they expected an even brighter future for kids from families like theirs. Many pointed to the internet as vital part of that. As Mr. Brown put it, “The world is getting smaller and more connected, facilitated hugely by social networking.” This helps kids combat isolation and forge “communities to talk to, share and learn from.”

Tracy Slater is an American writer living in Japan. She was recently interviewed about her book , The Good Shufu: Finding Love, Self & Home on the Far Side of the World .

Many thanks again to all who offered quotes and helped me write this piece!