Kathleen Kent's Blog

May 13, 2013

Upstairs Girls: Mattie Silks

The sign over Mattie Silk’s famous brothel in Denver read, “Men Taken in and Done For.” Considered a great beauty when she was younger, she ran one of the most expensive parlor houses in the city in the mid-1800′s. Unlike almost all of her contemporaries, though, she was never a prostitute herself, and began her successful sporting house career at nineteen. For more than forty years she operated her own pleasure palaces, boasting that she never took in a girl who wasn’t “experienced,” and kept the secrets of politicians and prominent businessmen.

The sign over Mattie Silk’s famous brothel in Denver read, “Men Taken in and Done For.” Considered a great beauty when she was younger, she ran one of the most expensive parlor houses in the city in the mid-1800′s. Unlike almost all of her contemporaries, though, she was never a prostitute herself, and began her successful sporting house career at nineteen. For more than forty years she operated her own pleasure palaces, boasting that she never took in a girl who wasn’t “experienced,” and kept the secrets of politicians and prominent businessmen.

One of the more colorful tales about this daring woman was that she had argued with another madam, Kate Fulton, over the affections of a man named Cort Thompson. Popular legend says that Kate challenged her to a pistol duel and they faced each other, six-shooters in hand, on Holladay Street, a notorious avenue of vice. Both women discharged their pistols at the same time. When the smoke cleared they had missed killing each other, but one of the bullets hit the object of their affections in the neck. Thompson survived, Kate was jailed and Mattie later married him. She eventually lived to regret being the winner of the duel as Thompson gambled away almost all of her hard-won savings.

She was once quoted as saying, “I went into the sporting life for business reasons and for no other. It was always a way for a woman in those days to make money and I made it. I considered myself then, and do now, a business woman.” The photograph shows her in her later years when she had lost most of her beauty, but she never lost her business sense.

Next week: “Chicago Joe” Hensley, The Irish Madam.

THE OUTCASTS, a novel, in part, about a young prostitute after the Civil War. Published October 1, 2013. (Little Brown Publishers)

April 18, 2013

Adventures in Bayou Country – Part 2

Doing on-site research for a book offers many different challenges. When I was doing research for The Traitor’s Wife, my second novel, I travelled to Wales and walked for miles through the Mt. Snowdon National Park, getting blisters on my feet, and chapped skin on my face from the raw wind and rain. My mother came with me as my “research assistant” and was very helpful in pointing out all of the ancient pubs, suggesting quite compellingly that they might prove instructive in our exploration of 17th century pastoral life. We visited quite a few of those venerable establishments the week we were in Wales and gained a new, if slightly muddle-headed, appreciation for history. The most threatening life form we encountered, though, apart from some inebriated WWII veterans at the George and Dragon on holiday from their wives, were some testy sheep that chased us across a field.

Research in the bayou country of Texas offered challenges of a different sort. I first visited the area southeast of Houston, close the Armand Bayou Nature Preserve, with my brother in the middle of summer, and I posted about some of the wildlife we encountered. In particular, a large alligator that seemed to love chicken nuggets. On a subsequent trip, I went with Dr. Tom Godwin—a Houston veterinarian and local historian, whose name I borrowed for one of the characters in my latest book—who cheerfully obliged my request (did I say that out loud?) to see an alligator up close. Evidently, gators like hamburger as much as they like chicken nuggets.

To be continued. . .

The Outcasts, a novel of 1870 Texas, will be published October 1, 2013.

April 4, 2013

Adventures in Bayou Country – Part One

When I was doing research for The Outcasts, I ventured with my brother—who is an avid historian of the American Civil War—into the bayous southeast of Houston. My novel is set, partially, in Middle Bayou (now called the Armand Bayou Nature Preserve) in 1870, the Reconstruction Era; a time of uncertainty, shattered hopes and, on occasion, violence. The greater area surrounding the still-swampy inlets and streams are residential developments, h0uses of ticky-tacky red brick, trailers with abandoned cars settled on cinderblocks and the occasional industrial park.

But once you enter the Armand preserve, a different environment unfolds: channels of slow-moving water, filled on either side with forests of elm and oak, thick underbrush, populated by 12-foot long alligators, wild boar, copperheads and banana spiders the size of dinner plates. OK, you’re thinking that because I’m writing about Texas I’m exaggerating. I’m not. The log floating in the photo above is not a log, it is in fact a large gator swimming alongside my brother and me as we walked on the rare foot path that followed the bayou’s edge. We kept a close eye on him, because alligators are fast coming out of the water. Very fast. And my brother, to get his attention so I could get a photo of him, had fed him the rest of our lunch: chicken nuggets. He followed us the whole distance of the path until it veered off into the underbrush again and we moved farther and farther away from the water.

I looked over my shoulder, though, for a good while wondering if I could run faster than my brother. To be continued next week. . .

The Outcasts will be published on October 1, 2013 (Little Brown)

Scroll down for more postings.

March 26, 2013

A Texan’s Confession About Guns

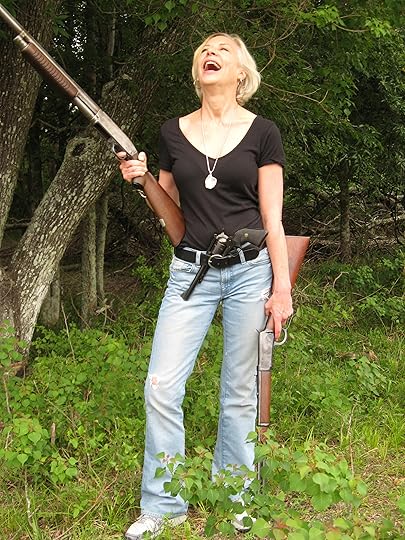

The laughing figure in the photo, holding a 32-30 Winchester and a 12-gauge shotgun, with a 44 mag pistol in her belt, is me. The Winchester belonged to my grandfather who used it to shoot a charging black bear, and I grew up playing on the rug he made from said bear. He wasn’t looking for the bear, it just found him.

The 12-gauge belonged to my dad who grew up hunting in the Piney Woods of Texas during the depression, and eating everything that he killed. And I mean everything! The pistol was borrowed from my brother for the photo; taken just before we ventured into the bayou country outside of Houston to do some research for my third book, The Outcasts, set a few years after the American Civil War. We didn’t kill anything other than a lot of mosquitoes, and carried the guns only for self-defense from very large alligators, wild boar and copperheads.

My dad and both grandfathers grew up hunting, although my dad in later years hunted exclusively with bow and arrow on horseback as he said it gave the animals a better chance of living for another day. They were all responsible gun owners and did not hunt for trophies, but out of necessity, and for protection as they lived at times out in the middle of nowhere. I grew up with a lot of guns in the house (it was Texas after all) and I practiced shooting, sometimes with my mom, who owns a pistol. When I went to New York City to live for the first time in 1980, my dad asked me if I wanted a gun for protection. I declined and for 20 years never regretted the decision. Dirty Harry, I am not. In fact, even with all the cultural acceptance of guns surrounding me, I am, and have always been, uncomfortable being around them.

How then do I explain my fascination with weaponry in my writing? I spent several years researching Civil War Era guns, in particular the Whitworth rifle, which is so rare that only a few remain in good condition. I wrote about the gun in an earlier posting: Long Distance Death. But writing characters who live by the gun, does not mean that the creator of those characters does too. After all, most crime writers who make a career describing murder most foul, are not serial killers.

Stephen King has said that writing his sometimes gory passages may have kept him from murdering some real life people who infuriated him—most likely a few critics. Talking, or writing, about it is not the same as doing it. And at the risk of announcing my vulnerable home-land condition, the only gun I own is a reproduction of an 1851 Navy Colt, black-powder revolver than takes forever to ready for firing. And you know what? I’m just fine with that.

The Outcasts will be published by Little Brown October 2013

See earlier postings below.

March 17, 2013

An Irishman Captures the West

Timothy O’Sullivan, who in 1872 photographed the grand, sweeping vista seen above, was of Irish ancestry. As a teenager he worked in the studio of the legendary 19th century photographer Mathew Brady, who is accepted by American scholars as the father of photo-journalism. (In my third novel, The Outcasts, Mathew Brady‘s photographic work is featured prominently as a reminder of the overwhelming loss of the men and boys who fought and died in the Civil War.)

A veteran of the war, O’Sullivan turned his hand to photographing the battlefield horrors in the first few years of the conflict before setting out on his cross-continental expeditions.

Using a box camera, he worked with Government teams as they explored thousands of miles of uncharted land. O’Sullivan was one of the first photographers to capture images of the Native American population along with an accompanying team of artists, fellow photographers, scientists and soldiers as they explored Colorado, Nevada and Utah. He drove a horse-drawn dark room wagon so that he could develop his images as they were taken. He spent seven years exploring the landscape and thousands of pictures have survived from his travels.

O’Sullivan died from tuberculosis at the age of 42 in 1882, a few years after the project had finished. His work, viewed by thousands, was largely responsible for many settlers risking the hardships of the West to begin anew after the devastation of the Civil War.

For earlier posts, see below:

March 4, 2013

The Rock Star and The Alamo

Because my third novel, The Outcasts, is set mostly in Texas—the state where I grew up—the anniversary of Texas Independence has made me think about how large the myths of Texas loom world wide. Stories of cowboys, hard-broke horses, man-killers and women who had no other choice but to make their living between the sheets to survive, have been told and retold in novels, films, songs and TV. When I was in Russia in the early ’90′s the most popular music was not head banging rock, but country and western. And believe me, a Hank Williams’ song sung in Russian is not easily forgotten. And the most popular TV series in Minsk was. . .wait for it. . .Dallas. Dubbed, that’s right, in Russian.

I also spent a few years, off and on, in Almaty, Kazakhstan, at the time working as a contractor for the U.S. Department of Defense (not building weapons, but helping to dismantle them). The native Kazakh people are very proud of their heritage dating back to Genghis Khan and are expert horsemen from the time they learn to walk. The only thing that seemed to impress them in my interactions with them was that I was from Texas. ”Cowboys. Bang, bang!.”

Yes, cowboys and mucho bang-bang.

That’s why it came as no surprise to me that Phil Collins is one of the largest single collectors of Alamo memorabilia. He recently published a book titled, The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey, and in his acknowledgments he wrote to “My mother and father, who encouraged my passion for the Alamo by letting me ‘do my thing’ and not changing the TV channel when Fess Parker was on.” In the book is a photo of the author at 5 years old, dressed as Davy Crockett with a coonskin cap and holding a six-shooter. Not a drum in sight. His book is filled with fascinating photos of letters, armaments and the men and women who fought for Texas Independence.

My brother got a chance to meet him at the book launch and signing in Houston and Phil said that it had been a life long dream to collect Alamo artifacts to feel a deeper connection to the time. He said, “I find the mystery of that era captivating.” He also said that, “if ever you want to start an argument with someone in Texas, the easiest way is to ask how did Davy Crockett die. . .”

Texans aren’t the only citizens who get fired up when someone yells, “Remember the Alamo!”

February 13, 2013

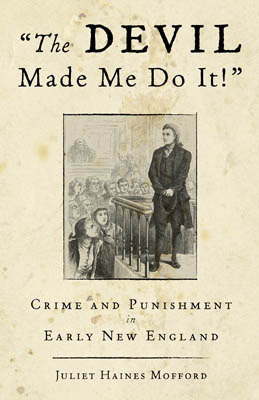

The Devil Made Me Do It!

The Devil Made Me Do It! is a fascinating book by historian and author, Juliet Haines Mofford , about the misdeeds of, and subsequent punishments by, the Puritans. It may seem at first glance to be an unusual choice for a Valentine’s Day posting but, for many of us, who we are—our habits and our psychology—was inherited from our stalwart, medieval-minded ancestors, The Puritans. They were courageous, but also intolerant of others who behaved outside of the saintly “norm.” They were, by our standards, very buttoned-down and obsessed with conformity. But, as it turns out they could also be romantic with their beloveds, and sometimes down right naughty.

I’ve asked Juliet a few questions about the Puritan mindset and got some surprising answers:

KK: You are a prominent historian, researcher and museum educator. Two of your eleven books received national awards from the American Association of State & Local History. You’ve also written many articles through the years on travel, education, biography and art history, as well as a number of plays about the Salem Witch Trials, American Presidents and such women as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Julia Ward Howe. But what first inspired your special fascination with 17th century New England history?

JHM: Early in my career I was at home with three children, writing feature articles for the Boston Globe, the New York Times, Scholastic Teacher, and other newspapers and magazines. I was contracted to write the history of the North Parish Church of North Andover, MA which was established in 1645. During my research I discovered that Anne Bradstreet, the first poet published in English in this entire country, had lived there. I also learned that during the 1692 Salem Witch Trials more people, including more children, were arrested on charges of witchcraft from Andover than from any other town in New England. I am still researching and writing about this little-known Andover Witch-Hunt!

KK: I think modern-day readers sometimes have an idea that the Puritans were more saintly or better behaved than their modern counterparts, an idea that was handed down to us from Victorian writers and historians. Do you think that the Puritans, who were Western European in their sensibilities and practices, were closer to the Elizabethans in their general “lustiness” than we would ordinarily view them?

JHM: The early settlers had their feet firmly planted in Old England. They brought with them to the New World many of their beliefs and social practices including folklore and magic which goes back to the Middle Ages. People who were born in England and who came to the Puritan colonies after the first settlers were generally less religiously-oriented, which proved a problem for the religious leaders of the Puritan communities concerned with keeping conformity with the community and harmony within families.

KK: It seems that pregnancy before marriage was not uncommon, and the citizenry were not uncomfortable with this state of affairs (i.e., sex before marriage) as long as the couple married in due time.

JHM: I believe that they were uncomfortable with sex before marriage since, in nearly every Puritan community, any couple whose baby arrived less than 9 months following marriage (performed by a magistrate, NOT by a clergyman) would be fined for fornication. Punishments were generally a fine of 20 shillings with several hours in the stocks or pillory or public chastisement before the entire congregation in the meetinghouse. However, after that, the couple was accepted within the community; their sin forgiven. Interestingly, the God worshipped by Puritans approved of any & all bodily pleasures among married couples. In fact, if a husband did not or could not perform and pleasure his wife, she could take him to court and even sue for divorce! (see Hannah Hutchinson case & others, in my book).

KK: Within the sanctity of marriage, couples were encouraged to “delight” in one another, and yet it’s hard for us to imagine the Puritans being so carnally-minded as to revel in physical love. Can you speak to this?

JHM: It wasn’t only the “common folk” of lesser stature in the hierarchy of the Puritan social order who were a lusty bunch. Early court records show evidence of “lusty swains and loving maids.” Puritan leaders were dedicated to creating a Utopian society and enforced a strict code of living, but most of us have inherited our ideas—familiar myths & misconceptions regarding Puritan life and 17th century New England—from the Victorian era, and from such authors as Hawthorne and Longfellow. I suggest reading John Winthrop’s love letters to his wife, for example, as well some examples from my book.

Following is a lovely poem by Anne Bradstreet to her husband—they had eight children together!

Letter to My Husband, Absent Upon Public Employment by Anne Bradstreet

My head, my heart, mine eyes, my life, nay, more,

My joy, my magazine of earthly store,

If two be one, as surely thou and I,

How stayest thou there, whilst I at Ipswich lie?

So many steps, head from the heart to sever,

If but a neck, soon should we be together.

I like the Earth this season, mourn in black,

My Sun is gone so far in’s zodiac,

Whom whilst I ‘joyed, nor storms, nor frost I felt,

His warmth such frigid colds did cause to melt.

My chilled limbs now numbed lie forlorn;

Return; return, sweet Sol, from Capricorn;

In this dead time, alas, what can I more

Than view those fruits which through thy heat I bore?

Which sweet contentment yield me for a space,

True living pictures of their father’s face.

O strange effect! now thou art southward gone,

I weary grow the tedious day so long;

But when thou northward to me shalt return. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Devil Made Me Do It:Crime and Punishment in Early New England, can be purchased on Amazon in paperback, and is also downloadable for e-readers such as Kindle. Juliet has just completed a new book, to be released soon, titled, Abigail Accused!-The True Story of A Survivor of the Salem Witch-Hunt

January 18, 2013

Long Distance Death

In 1864, during the battle of Spotsylvania, Union General John Sedgwick berated his cowering troops for trying to stay hidden from Confederate sharpshooters positioned over 1,000 yards away. Sedgwick marched up and down the barricades telling them, “What? Men dodging this way for single bullets. . .I am ashamed of you. They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Seconds later he was felled with a sniper’s shot, likely fired from the deadly, and elusive, Whitworth rifle.

In 1864, during the battle of Spotsylvania, Union General John Sedgwick berated his cowering troops for trying to stay hidden from Confederate sharpshooters positioned over 1,000 yards away. Sedgwick marched up and down the barricades telling them, “What? Men dodging this way for single bullets. . .I am ashamed of you. They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Seconds later he was felled with a sniper’s shot, likely fired from the deadly, and elusive, Whitworth rifle.

The Whitworth was a British-made, single-shot and muzzle-loaded rifle that was used almost exclusively by Confederate sharpshooters. They were also rare during the Civil War as there were only about 200 imported to the States, and there are very few left in good condition today. In early trials—Queen Victoria fired the first test shot—the Whitworth outperformed the Enfield rifle by hitting targets up to 2,000 yards away and it was greatly feared by Union troops facing the well provisioned and well practiced (and nearly invisible) sharpshooters firing at them from impossible distances.

In my new historical novel, Lucinda, (to be published September 2013) the Whitworth rifle plays an important part of the narrative, both as an instrument of death as well an object of beauty and skill. In many ways it proved to be my most challenging endeavor to date: confronting authentically the violence and uncertainty of the time as a researcher and writer, and reconciling those sensibilities with my own (more modern-day) discomfort with gun play.

October 29, 2012

How to Spot a Witch

In honor of Halloween, I thought I’d write briefly about a book that was used for hundreds of years by Men of Science—although the science of the middle ages—and Men of Theology—zealots who used heavily biased religious texts against women who challenged the narrow definition of a female’s place in society, or who were mentally or physically unbalanced—to identify and prosecute witches.

In honor of Halloween, I thought I’d write briefly about a book that was used for hundreds of years by Men of Science—although the science of the middle ages—and Men of Theology—zealots who used heavily biased religious texts against women who challenged the narrow definition of a female’s place in society, or who were mentally or physically unbalanced—to identify and prosecute witches.

Called the MALLEUS MALEFICARUM, meaning “Hammer of the Witches” in Latin, it was written in 1486 to refute the more rational citizens of the Tyrol region of Germany who doubted the existence of witches. The Church had officially denied the existence of witches since the time of Charlemagne, who in fact outlawed the practice of witch burning, calling it a pagan superstition. But the wide distribution of the Malleus, thanks in part to the development of the printing press, brought a resurgence of witch hunting in Europe and in the New World.

The author of the book was one Heinrich Kramer who was initally thrown out of his home district for being a crank. Called a “senile old man” by his local bishop, it has been theorized that the book was his act of vengeance against the established clergy in particular and women in general. And what a bloody vengeance it was. As many as 60,000 people, mostly women, were burned at the stake in Europe between 1480 and 1750.

According to the Malleus “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.” A very telling insight into the mindset of the author, and of the prosecutors of the unfortunate women labeled as confederates of the Devil. There were many stages of investigation, but a physcial examination almost always uncovered a wart or a mole that could be claimed to be the “witches teat” from which she fed her familiar—a cat, frog, newt, etc.—a demon in disguise.

We treated our witches a little more kindly here in the colonies in that we didn’t burn them at the stake. We only hanged them. But the 20 men and women who were killed in Salem in 1692 (my 9X great grandmother, Martha Carrier, among them) were some of the last wholesale victims of the Malleus.

October 15, 2012

Mankillers: Cullen Baker

Previously, I posted about Wild Bill Longley, the true-life “mankiller”, who served as a model for a main character—a serial killer—in my newest novel about Reconstruction era Texas (as yet untitled).

Previously, I posted about Wild Bill Longley, the true-life “mankiller”, who served as a model for a main character—a serial killer—in my newest novel about Reconstruction era Texas (as yet untitled).

But there were scores of other hot-headed, amoral killers roaming the interior of Texas during the second half of the 1800′s. Cullen Baker (pictured here) was born in Tennessee and served in the Confederate Home Guard in Arkansas during the Civil War. The CHG was a homely-sounding name for a group of rangers who raped, pillaged and murdered their way through Arkansas and Missouri, indiscriminately killing unionists and confederates alike. After the war, he and his gang members killed between 50 and 60 people, many of them freed slaves.

By all accounts, he was a heavy drinker which not surprisingly fueled his killing temper, but he chose unwisely in love as his violent death was linked to his second wife. There are two versions of his death. The first recounts that he and a cohort were both poisoned by strychnine by his wife’s family and then shot to death. The second version says that Cullen was shot by his wife’s lover, a school teacher, in his own home.

The Western writer, Louis L’amour wrote about him in several novels, adding him to the pantheon of better known gunfighters such as Billy the Kid, and the James-Younger Gang.