Peter Wolfendale's Blog

November 1, 2025

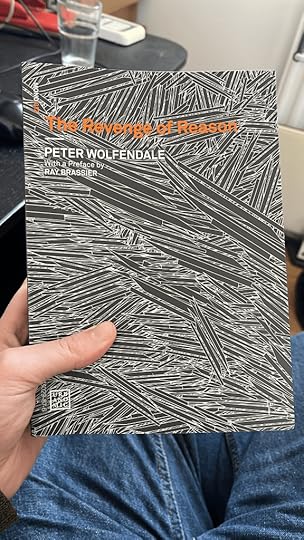

The Revenge of Reason is here!

It’s been a long time coming, but my second book, The Revenge of Reason, is finally available to buy. There are so many things in here that were written or given as talks long ago but never actually published, and it’s nice to know people will finally be able to reference them properly. As readers of the blog may already know, I’ve struggled to write consistently and struggled even more to publish any of it in the last 10 years, due to a mixture of bipolar disorder, a couple surprise health problems, inconsistent employment, and a myriad of bad choices. Yet I’ve somehow managed to build a modest reputation as a philosopher worth paying attention to, and acquired a small following of people who pay such attention. Thanks to everyone who has listened and given support over the years, this one is for you.

The book collects essays written over the last 15 years or so, along with a couple interviews, ranging across a wide variety of topics, covering everything from realist metaphysics to the philosophy of games. But it begins with a sequence of 5 essays written over the last 10 years that between them construct a coherent neorationalist perspective on the nature of mind, agency, selfhood, and value. This book might not contain a fully articulated philosophical system, but it does present the outline of an integrated worldview, in which questions about conceptual revision, personal autonomy, and the nature of beauty intersect, anatomizing the deep philosopical bond between reason and freedom.

June 22, 2025

TfE: On Post-Searlean Critiques of LLMs

Here’s a recent thread on philosophy of AI from Twitter/X, in which I address rather popular arguments made by Emily Bender and others to the effect that LLM outputs are strictly speaking meaningless. I think these argument are flawed, as I explain below. But I think it’s worth categorising these as post-Searlean critiques, following John Searle’s infamous arguments against the possibility of computational intentionality. I think post-Searlean and post-Dreyfusian critiques form the main strands of contemporary opposition to the possibility of AI technologies developing human-like capacities.

I think it’s maybe worth summarising why I think post-Searlean critics of AI such as Emily Bender are wrong to dismiss the outputs of LLMs as meaningless. Though it’s perhaps best to begin with a basic discussion of what’s at stake in these debates.

Much like the term ‘consciousness’, the term ‘meaning’ often plays proxy for other ideas. For example, saying systems can’t be conscious is often a way of saying they’ll never display certain degrees of intelligence or agency, without addressing the underlying capacities.

Similarly, being able to simply say ‘but they don’t even know what they’re saying’ is a simple way to foreclose further debate about the communicative and reasoning capacities of LLMs without having to pick apart the lower level processes underpinning communication and reasoning.

Now, I’m not going to argue that LLMs in fact know what they are saying, but simply pick apart what I see as over-strong arguments that preclude the possibility that full-blown linguistic competence might be built out of technologies that borrow from these systems.

(If you want a summary of the debate over Bender’s arguments from the linguistics side, see this blog post: https://julianmichael.org/blog/2020/07/23/to-dissect-an-octopus.htmlâ¦)

So, I think there are two main arguments here: 1) that no matter how much LLMs emulate the ‘form’ of language by encoding structural relations between symbols, their outputs lack content because these symbols aren’t ‘grounded’ by practical relations to the things they represent.

And 2) that no matter how much LLMs emulate the ‘form’ of language by mirroring coherent dialogical interaction, their outputs lack content because the system’s are incapable of the communicative intent underpinning genuine speech acts such as assertion.

I think (1) is more or less cope at this point. There’s not nothing to it, but since the advent of word2vec there’s been a steady stream of practical vindications for structuralism (even if the remaining structuralists in the humanities have largely ignored them).

(A recent example of such a vindication can be found here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.21073)

Now, I’m an inferentialist (which, per Jaroslav Peregrin, is a type of structuralism). I think the core component of meaning is given by the role sentences play in ‘the game of giving and asking for reasons’ and the contributions component words make to these inferential roles.

LLMs are not designed to distil inferential relations between words and concatenated sequences thereof, but they do capture them in the course of distilling relations of probabilistic proximity. They also capture the semiotic excess of loose connotation over strict implication.

Inferentialism does have a few things to say about word-world relations: 1) GOGAR extends beyond pure inference to include non-inferential language-entry moves (perception) and language-exit moves (action); this is how expressions get specifically empirical or evaluative content.

And 2) the role of the representational vocabulary we use to make word-world relations explicit (‘of’, ‘about’, etc.) is to enable us to triangulate between divergent perspectives on the implications of our linguistically articulated commitments.

LLMs obviously lack the capacity for perception or action. It is this lack that Bender argues precludes their symbols from being grounded. However, there are many symbols we use that simply aren’t grounded in this way, most importantly mathematical terms and unobservables.

The semantic content of mathematical statements is more or less purely inferential, lacking any direct connection to perception or action. Some (e.g., Derrida) have used this to argue that mathematics is an inherently meaningless game of symbol manipulation, but this is silly.

Mathematics is superlatively capable of investigating its own content, as the history of formal logic and semantics demonstrates. To deny mathematics inherent meaning is to falsify it.

Unobservables (e.g., ‘electron’, ‘black hole’, ‘allele’, etc.) are more significant however. These are terms for entities we can neither directly perceive or act upon, but engage with through experimental and technological practices mediated by complex inferences.

Advocates of the importance of grounding tend to argue that these terms are grounded indirectly by their relations to terms that are grounded directly in experience, such that we couldn’t have meaningful terms for unobservables without some meaningful terms for observables.

Fair enough. But the question is precisely how these word-world connections are inherited. Must it be intra-personal, or can it be inter-personal? Need a physicist be able to describe and calibrate all the instruments in the chain that leads to his black hole data to discuss it?

It seems reasonable to say that two students of physics can have a meaningful discussion of black holes without yet knowing much about the elaborate processes through which they are detected. Indeed, even two lay people can probably have a simple chat about them.

But then, it equally seems that they might have a simple chat about things they haven’t seen, but which aren’t strictly unobservable (e.g., Siberian tigers, the NYSE, bowel cancer). What constrains them here is not their own capacities for perception/action, but those of others.

Meaning is articulated not just by relations of inference, but also relations of deference. Lay people defer to physicists when it comes to black holes. The blind defer to the sighted when it comes to the behaviour of light and pigment. Our talk is grounded by social constraint.

We might want to say that some people have richer understanding of words than others, either because they have a more profound grasp of their inferential complexities or because they have direct practical experience of their referents. But there’s legitimate gradation here.

We thus might think it is feasible for a computer system that lacks perceptual and practical capacities of any kind outside of its communicative channels to feasibly be constrained (and its output thereby grounded) by its relations to the social community whose language it uses.

The question is whether relations between LLMs and the communities whose linguistic behaviour they compress is sufficient to really sustain this. There are some legitimate reasons to think it isn’t. And this brings us back to representational vocabulary.

There’s an emerging consensus that LLMs can develop something like discrete ‘representations’ of certain features of the world in order to predictively generate text ‘about’ them. Yet there’s also a general skepticism that these compose anything like a genuine ‘world model’.

Working backwards from world models, the real challenge is that LLMs are not really interested in truth. This is partly to do with what get’s colloquially called ‘hallucination’ – the tendency to fabulate plausible but false statements. In other words, to misrepresent the world.

But perhaps more important is the problem of consistency. The ‘attention’ windows deployed by LLMs are very large, and enable them to remain mostly self-consistent within a given conversation, but if you push them too far they can quite easily contradict themselves.

More significantly, they will, with no to little prompting, express conflicting opinions across different conversations. They excel at maintaining a range of locally cohesive dialogical interactions, but underlying these there is no globally coherent worldview.

There are in-context hacks that LLM proprietors use to mitigate these problems to some extent. They can secretly frontload our interactions with lists of facts that discourage hallucination about the relevant topics, producing a very crude ersatz world-model.

But not only do these only stabilise outputs on a tiny of fraction of topics the LLM can address, the system cannot update them in response to its interactions with users, even if they may be convinced to ignore them in the context of the current conversation.

And here is the nub of the difference between the social constraint that the community of human language users exercise upon one another and that we exercise on LLMs trained on our behaviour. We aren’t just pre-trained, we continue to train one another through interaction.

And crucially, when these interactions turn upon conflicts of opinion, we can effectively calibrate the way that we involve the world in resolving them. We can establish that we’re talking *about* the same things, even if we disagree about the implications of what we’re saying.

The obvious response to this is that much if not most of the actual social pressure that shapes linguistic usage simply doesn’t involve this sort of explicit clash and rational navigation of competing worldviews in which we chase down the threads that tie our words to the world.

If mostly what we do is just tacitly correct one another’s speech, is this distributed network of behavioural nudges any more significantly constrained by the world itself than the process of distilling behaviour wholesale and then finessing it with RLHF and in-context tweaks?

I think that whatever significance we ultimately grant to explicit disagreement, we should probably recognise that these two forms of implicit constraint (social pressure/ML) are not fundamentally different in kind, even if in degree, and even if one is parasitic on the other.

This brings us to Bender’s second argument regarding the absence of communicative intention, which can be usefully approached from a similar direction. I’ll accept the premise that LLMs don’t possess communicative intentions, but aim to show this is less relevant than it appears.

To unpack the argument, the idea is that when interpreting what an LLM means by what it says (e.g., given ambiguities or unstated implications), it makes no sense to assume there’s a correct way to decide between options, as it simply cannot intend us to pick one.

In other words, even if LLM outputs display some form of literal meaning (contra argument 1) they cannot display any form of speaker meaning. More generally, we cannot interpret the force of outputs as making specific sorts of speech acts (assertion, question, request, etc.).

I think the best counter example to this argument is also pretty illustrative of how LLMs fit into the existing linguistic community: rumours. These are something like free-floating assertions disconnected from their origin, and possibly without one given whisper mutations.

To pass on a rumour is not exactly to make an assertion, but it doesn’t necessarily erase any potential epistemic valence or preclude the possibility of interpretation. We can even still interpret the intentions of the phantom speaker, even if they never really existed.

If you want a comparable example of such seemingly untethered interpretation, consider the energy still put into interpreting (and aiming to correctly translate) figures like Homer.

The output of an LLM is a lot like a rumour: a statement/text produced by a distributed social process in a way that gives it obvious semantic content but severs the deferential links that articulate the social process of justification.

I’ve elsewhere likened LLMs to rumour mills. It’s almost as if we’ve learned to gossip with the distributed social process directly, without passing through its nodes. A fully automated rumour mill we can even inject suggestions into and see them come back fully fleshed out.

Of course, an LLM is much less like an evolving group dynamic than a snapshot of an egregore, and far more tightly focused in the way it develops prompts. There’s emergent novelty where new patterns or capacities arise from the sheer amount of behaviour they compress. But still.

Just as we could argue that the way LLMs’ outputs might be grounded (however poorly) by their connection to the implicit process of distributed social constraint, we can argue that they display something like speaker intention (however poorly) in virtue of the same connection.

Though we may justifiably claim that no random string of shapes worn in the sand by waves can mean anything no matter how much they might look like letters, we must admit that the probabilistic processes underpinning LLMs are closer to speech than they are to waves on the sand.

Now, I’m not claiming these systems literally have communicative intentions, but rather that the way they’re embedded in a socio-linguistic context makes them as it were ‘good enough for government work’. We can disambiguate LLM outputs in ways we can’t disambiguate the sand.

I should add that our ability to dialogue with LLMs certainly seems to help in this regard, as we can ask them to clarify what they mean. There are legitimate questions as to what extent such clarifications are post-hoc fabulations, but such questions often apply to humans too.

This has been a long thread, and I should try to wrap it up, so let me try and weave my different concerns together. If I agree with Bender that LLMs are not full blooded agents, lacking determinate beliefs and intentions, why do I think it is important to dispute her arguments?

A pervasive problem in AI debates is setting the bar for what counts as mindedness. One sees this in AGI talk, where this can mean either task flexibility somewhat less than an average human, or problem solving capacity greater than human society, depending who is talking.

I worry something similar is going on with meaning. Some want to claim that LLMs already fully grasp it because they generate surprisingly coherent gossip, and others want to claim they grasp nothing because they aren’t full-blooded agents who say only and exactly what they mean.

We have to recognise that most of what humans do, linguistic and otherwise, simply isn’t the more high-bar stuff that many (including me) leverage to distinguish us from mere animals/machines (take your pick). This means we have to be more careful in drawing such distinctions.

This goes double when the high/low bars are blurred. We have built machines that are superhumanly good at gossip. They can gossip at length and in detail about some subjects greater than some humans will ever sincerely explain things they really know.

I’m fond of Kant’s idea that there is no consciousness without the possibility of self-consciousness. What defines self-consciousness here is precisely what I’ve said LLMs lack: something like an integrated world model, and something like intentional agency.

You can read this as denying that there is consciousness/understanding in systems that do not act as full-blooded rational agents, keeping track of their theoretical and practical commitments, giving and asking for reasons, and generally striving for consistency.

You might then treat those systems (animals/machines) as completely different in kind from self-consciousness rational agents, as if they have absolutely nothing in common. But this is the wrong way to look at things.

For the most part inference modulates rather than instigates my behaviour. I say and do what seems appropriate (likely?) in a given context, but I can override these impulses, and even reshape them when they conflict with one another or with my more articulated commitments.

My habitual behaviour is conscious because it can be self-consciously modulated. From one perspective nothing much is added on top of animal cognition, from another, it makes all the difference. This equally applies to my linguistic behaviour.

I often speak without thinking. Maybe I mutter to myself. Maybe I just parrot a wrote phrase. Maybe I say something I donât really mean. Maybe I donât even know what it meant. But often it makes sense and is retrospectively judged to have the neat stamp of communicative intent.

Sometimes I gossip. Sometimes Iâm just spewing things that sound plausible without much thought, and Iâm not paying too much attention to how they fit into my wider rational picture of the world. Sometimes Iâm less reliable and informative than an LLM.

I can still be pulled into the game of giving and asking for reasons, forced to full self-consciousness, and thereby put my idle talk (Gerede) to the test. Thatâs the difference between me and the LLM. The difference that makes the difference. But it doesnât erase the similarity.

Iâm also fond of Hegelâs idea that there is no content without the possibility of expression. I think this is recognisably a development of Kantâs thought. The twist is that it lets us read âpossibilityâ more broadly. Weâre no longer confined to an individual consciousness.

We are then capable, for instance, to talk about the content of historically prevalent social norms that have thus far been implicit, making them explicit and critically assessing them in a manner that might accurately be described as a sort of social self-consciousness.

And I suppose this is my point: LLMs are awkwardly entangled in the system of implicit norms that constitute language. Theyâre incapable of true self-consciousness/expression (rational revision) but they feed into ours in much the way we feed into one another.

Theyâre in the game, even if theyâre not strictly playing it. And that counts for something. Itâs enough to maybe say we know what they mean from time to time. Kinda. Perhaps as we do for one another when weâre not quite at our most luminously intentional.

And so, though I do think there are important architectural changes required before we can say *they* know what they mean, these are maybe less extreme than Benderâs arguments would suggest. Best leave it at that.

[image error]

P.S.

As an addendum to yesterdayâs big thread on LLMs and meaning, there was an argument I was building towards but didnât really express regarding the literal/speaker meaning distinction and the dependency between the two.

We can grant this argument if we interpret it to mean that, e.g., it would not make sense to say that LLM outputs were even literally meaningful if they werenât embedded in a culture of human speakers with communicative intentions.

But Iâve been arguing that we should resist the narrower interpretation that says we canât say that LLM outputs have literal meaning unless they themselves are capable of fully formed communicative intentions.

I want to add to this the additional claim that there is a dependency running in the other direction. This turns on the idea that possessing communicative intentions requires the capacity for intentional agency more generally.

Now, I have quite strict conception of agency. I think it involves a kind of in principle generality: the ability to form intentions oriented by arbitrary goals. The representation generality of language opens us up to this, allowing us to desire all sorts of ends and means.

There are many people who disagree with me about this, usually because they think animals of various sorts are on an equal agential footing with us, and occasionally because they want to say the same about extant artificial agents.

But even if you disagree with me on the idea that we need some thing like the articulated semantic contents of literal meaning to open us up to the full range of possible intentions, itâs hard to argue that specifically communicative intentions are possible without it.

Speaker intention does not emerge from the animal world fully formed, only waiting for suitable words to express it. Thereâs obviously a more complex story about how it is bootstrapped, with literal and speaker meaning progressively widening one anotherâs scope.

But in the artificial realm, it would not be unreasonable for this story to unfold differently, and for the appropriation of an expansive field of literal meanings to form the framework within which it becomes possible to articulate more refined communicative intentions.

And my point in the original thread was that this fairly plausible story is precisely what the post-Searlean obsession with âmeaningâ forecloses, requiring the perfectly crisp speaker meanings of world-engaged agents to emerge all at once as a fully integrated package.

I see this as the general form of Leibniz’s Mill type arguments, of which Searle’s is exemplary and Bender’s is a distant descendent: a refusal to countenance the possibility of the system’s parts without the whole.

For me, the tricky thing has been to be able to acknowledge that there is something important missing without systemic integration (self-consciousness/rational agency proper), without rejecting potential components witnessed in isolation (semantic scaffolding).

Down that path lies madness, i.e. Searle’s claim that there’s got to be some special property of our parts that allows them to compose the intentionally saturated whole.

[image error]

October 18, 2024

TfE: The Problem with Bayes / Solmonoff

Here’s a recent thread musing about problems with Bayesian conceptions of general intelligence and the more specific variants based on Solmonoff induction, such as AIXI. I’ve been thinking about these issues a lot recently, in tandem with the proper interpretation of the no free lunch theorems in the context of machine learning. I’m writing something that will hopefully incorporate some of these ideas, but I do not know how much detail I will be able to go into there.

If the problem with Bayesianism is that it takes representational content for granted, the problem with Solmonoff induction is that it obviates representation entirely, objuring semantics in favour of foundational syntax. Each ignores the underlying dynamics of representation.

By which I mean the non-trivial process through which singular objects are individuated (Kantâs problem) and the general types and predicates that subsume them are revised (Hegelâs problem). Semantic evolution is a constitutive feature of epistemic progress.

The key point is this: if you model epistemic progress as a process of exhausting possibilities, then you need to have a predetermined grasp of the possibility space. Either this is purely combinatorial (mere syntax) or it is meaningfully restricted (added semantics).

The former tends toward computational intractability (and effective vacuity), while the latter risks drawing the bounds of possibility too tightly. The one fails to create a truly coherent possibility space, the other fails to create a truly exhaustive one.

There are two ways around this: one is to insist on semantic atomism (a complete set of atoms from which all meaningful possibilities can be combinatorially generated), the other is to utilise algorithmic information (a universal syntax modulo choice of UTM). Fodor or Solmonoff.

Itâs a bit trickier to show what is wrong with these perspectives, but I think their errors are complimentary and instructive. It all comes down to what differentiates the semantic content of empirical terms from those of mathematical terms: their role in observation and action.

Semantic atomism is forced to countenance basic observations and actions. This actually gets formalised in AIXI extensions of Solmonoff induction. Itâs important to stress that epistemology and philosophy of action have spent much of the 20th century critiquing these ideas.

Solmonoff induction folds observation and action into the structure of its Universal Turing Machine and its interface with the environment, i.e., whatever I/O side effects it is capable of. Meaning is provided by black-box computational dynamics.

This black-box character is supposed to be a selling point, insofar as it is precisely what obviates representation. But what it really does is remove any possibility of distinguishing distinct algorithmic hypotheses, e.g., about specific phenomena, states, or laws.

All the Solmonoff engine can do is test hypotheses about the universe as a whole, precisely insofar as the universe is indistinguishable from another UTM generating undifferentiated binary output. The only question is âwhat is the binary expansion of realityâ.

To temper this, as AIXI seems to, you need to open up the black box and identify the basic operations that structure the underlying binary input. The important question is: why would you want to temper it? The relevant answer is: because otherwise it is completely useless.

If you donât know how the binary expansion is encoding the features of the world you might possibly be interested in, then you cannot use its hypotheses to predict and manipulate anything specific. It is as useful as the binary expansion of pi containing everything.

To be maximally clear: something cannot count as a general problem solver if it is incapable of solving any specific problems. There is an explanatory gap between optimally predicting any binary stream given an arbitrary UTM and generating discrete usable hypotheses.

There is a related and equally instructive problem here regarding the semantic content of mathematical terms and statements. One might be inclined to think that the lack of connection to observation and action might obviate any representational problems in the mathematical case.

Itâs possible to imagine cutting up the world explicitly along AIXI lines and running Solmonoff induction on the pieces, developing progressively better specific hypotheses. But could one do this in a way that would allow one the prove mathematical conjectures? In a word, no.

In more words, Iâm sure itâs possible to create sequences that canât be successfully predicted without proving some corresponding mathematical theorem. Maybe this can even be done for every theorem. But it would generally depend upon encodings that presupposed the proof.

Mathematics as such is dissolved into the underlying computational processes, either as a hard coded feature of the instruction set of the UTM, or as an emergent feature of the program/hypothesis that is generating predictions. A means but never an end.

The ultimate point that Iâm working towards is that whatever semblance of discrete knowledge is accrued by Solmonoff induction cannot play any significant role in guiding where the process goes next. New maths is not incorporated into the UTM. New science does not evolve.

The only sense in which there is any intrinsic progress in which knowledge is built upon is the trivial sense in which any such ampliative algorithmic process would also be run by SI, just insofar as it runs every possible algorithm.

Crucially, knowledge is built on not just in the sense that fixed premises can serve as the basis for new inferences, but also that existing conceptsâ specific inadequacies suggest a range of options for revision going forward. Computational hysteresis, not brute force search.

To give a related example, Iâm a big fan of predictive coding approaches to cognition, which seem superficially similar to SI insofar as they treat experience as prediction (less superficially from the Bayesian brain perspective). However, they treat error very differently.

A predictive coding system has a series of representational layers ranging from the concrete to the abstract (e.g., edges>faces>objects>types>etc.) and two signals: prediction (abstract>concrete) and error (concrete>abstract). All the world provides is error.

This looks superficially similar to SI because all the world provides at each SI step is a bit that lets you discard every program that failed to predict that bit. But error works very differently in the PC case, in at least two ways.

First, there is a tolerance for error. If my current world model predicts that I will hear a loud sound from a certain direction but gets the pitch slightly wrong, that is no reason to substantially modify the model. The error signal doesnât get passed up to the next layer.

Second, there is specificity of error. Any variance between my predictions and my sensory input trickles up through the representational layers until it reaches its appropriate level, triggering a specific and suitable correction that then cascades back down. Rinse and repeat.

It is this looping process of specific error and appropriate response that enables the modelâs predictions to hone in on a correct representation of the world. It is how error gets used that constitutes intelligence in this context.

Iâd argue that the same is broadly the case in the Lakatosian model of progressive research programs, allowing anomalies to rise to the correct level of abstraction and elicit appropriate responses. But thatâs beside the point.

The point is that the only way Solmonoff induction simulates a predictive coding system is in the negative. Every time a simulated PC program gets an error bit it is discarded. It just so happens that every possible PC program that predicted the correct bit is still running.

Of course, these programs are thereby necessarily more complex than those that contain no instructions governing the use of error signal at all, and so will be ranked less probable than their purely predictive counterparts.

Any hypothesis that algorithmically encodes how it should be modified in response to surprisingly input from the environment is first discounted and then eliminated before it gets the chance to try, because the modified versions have already been running all along.

And this for me demonstrates the real problem with Solmonoff induction, but by extension Bayesianism more generally, at least insofar as they are conceived as methods of exhaustion. To the extent that they are incomputable ideals to be approximated, they idealise the wrong thing.

The âshortcutsâ required to make them not just computable, but tractable, essentially involve learning how to make intelligible the specific error signals that steer us toward limited ranges of options for revising our beliefs and the concepts that constitute them.

This is why a few years ago I said that the real coming intellectual conflict is between Bayesian positivists and cybernetic falsificationists. There is a deep connection between semantics, error, and the anticipation of revision that we have yet to fully appreciate.

Iâll finish with one final thought, as I suspect that AIXI fans will not find my gestures toward critiques of basic observations/actions to be sufficiently rigorous. Can we see different representational layers of PC systems as in some sense mapping the same possibility space?

In some sense, everything is being cashed out at the bottom, in the most concrete layer, where our semantic atoms are to be found. Why bother with the tower of abstractions built on top of this bedrock? Canât we just see them as combinatorial constructions/restrictions?

I think it worth pondering the possibility that the possibility spaces do not neatly map onto one another, and that this is a feature not a bug. Mark Wilson has made the case for this at the level of scientific description already.

Letâs call it there.

[image error]May 20, 2021

TfE: What Kind of Computational Process is a Mind?

Here’s a thread from the end of last year trying to reframe the core question of the computational theory of mind. I’m still not entirely happy with the arguments sketched here, but it’s a good introduction to the way I think we should articulate the relationship between philosophy of mind and computer science. There are a lot of nuances hidden in how we define the terms ‘computation’, ‘information‘, and ‘representation’, if we’re to deploy them in resolving the traditional philosophical problems of mindedness, but these nuances will have to wait for another day.

There are many complaints made about classical computational theory of mind (CCTM), but few of them come from the side of computer science. However, in my view, the biggest problem with first and second generation computationalists is a too narrow view of what computation is.

Consider this old chestnut: “Gödel shows us that the mind cannot be a computer, because we can intuit mathematical truths that cannot be deduced from a given set of axioms!”

The correct response to this is: “Why in the ever-loving fuck would you think that the brain qua computational process could be modelled by a process of deduction in a fixed proof system with fixed premises?”

What this question reveals about those who ask it and those who entertain it is that they don’t really appreciate the relationship between computation and logic. Instead, they have a sort of quasi-Leibnizian folk wisdom about ‘mechanical deduction’.

(If you want an example of this folk wisdom turning up in philosophy, go read Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, which contains some real corkers.)

Anyway, here are some reasonable assumptions about any account of the mind as a computational process:

1. It is an ongoing process. It is an online system that takes in input and produces output in a manner that is not guaranteed to terminate, and which for the most part has control mechanisms that prevent it behaving badly (e.g., catastrophic divergence).

Interestingly enough, this means that the information flowing into and out of the mind, forming cybernetic feedback loops mediated by the environment, is not data, but co-data. This is a very technical point, but it has fairly serious philosophical implications.

So much of classical computationalism works by modelling the mind on Turing machines, or worse, straight up computable functions, and so implicitly framing it as something that takes finite input and produces finite output (whose parameters must be defined in advance).

Everyone who treats computation as a matter of symbol manipulation, both pro-CCTM (Fodor) and anti-CCTM (Searle), has framed the issue in a way that leads directly to misunderstanding this fairly simple, and completely crucial point.

2. It is a non-deterministic process. When it comes to the human brain, this is just factually true, but I think a case can be made that this is true of anything worth calling a mind. It is precisely what undermines the Leibnizian Myth of mechanical deduction.

This non-determinism can be conceived in various ways, in terms of exploitation of environmental randomness, or in terms of probabilistic transition systems (e.g., Markov chains). The deep point is that any heuristic that searches a possibility space for a solution needs this.

Some problems are solved by following rules, but others can only be solved by finding rules. Any system that learns, which means everything system that is truly intelligent, requires essentially fallible ways of doing the latter. Indeed, it is an evolving collection of these.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, what Gödel proves is that even mathematics is essentially creative, rather than mechanically deductive. Furthermore, it’s a creativity that in principle cannot be modelled on brute forcing. Why would we model other creativity this way?

Yes, mathematics does involve applying deterministic rules to calculate guaranteed results to well defined problems, but how do you think it finds these rules? Mathematicians search for well-formed proofs in a non-totalisable space of possible syntactic objects.

If we cannot brute force mathematics, why would we think that we could brute force the empirical world? Even if we could, there is not enough time nor enough resources. We are left to heuristically search for better non-deterministic heuristics.

3. It is a system of concurrent interacting subsystems. This is also an obvious fact about the human mind qua computational process, at least insofar as the structure of the brain and the phenomenology of our inner lives are concerned. However, it is the most contentious point.

There’s a good sense in which there is an intrinsic connection between concurrency and non-termination and non-determinism, at least insofar as the interactions with our environment just discussed suggest that we fit into it as an actor fits into a larger system of actors.

However, a skeptic can always argue that any concurrent system could always be simulated on a machine with global state, such as a Turing machine in which not just one’s mind but one’s whole environment had been unfolded onto the tape. Concurrency in practice, not principle.

This is where we get into the conceptual matter of what exactly ‘interactive computation’ is, and whether it is something properly distinct from older non-interactive forms. There’s a pretty vicious debate between Peter Wegner and Scott Aaronson on this point.

It all comes back to Samson Abramsky’s framing of the difference between two different ways of looking at what computation is doing, i.e., whether we’re interested in what is being computed or whether we’re interested in how a process is behaving. This is deeply philosophical.

Abramsky asks us: “What function does the internet compute?”

The proper response to this question is that it is nonsensical. But that means that we cannot simply pose the problems that computational systems solve in terms of those computable functions delimited by the equivalence between recursive functions, Turing machines, lambda calculus, etc.

This becomes incredibly contentious, because any attempt to say that (effective) computation as such isn’t defined by this equivalence class can so easily be misinterpreted as claiming that you are tacitly proposing some model of hypercomputation.

The truth is rather that, no matter how much we may use the mathematical scaffolding of computable functions to articulate our solutions to certain problems, this does not mean that those problems can themselves be defined in such mathematical terms.

Problems posed by an empirical environment into which we are thrown as finite creatures, and forced to evolve solutions in more or less systematic ways, no matter how complex, are not mathematically defined, even if they can always be mathematically modelled and analysed.

Solutions to such problems cannot be verified, they can only be tested. This is the real conceptual gulf between traditional programming and machine learning: not the ways in which solutions are produced, but the ways in which the problems are defined. The latter obviates specification.

For any philosophers still following, this duality, between verification and testing, is Kant’s duality between mathematical and empirical concepts. If one reads ‘testing’ as ‘falsification’, one can throw in Popper’s conception of empirical science into the mix.

My personal view is that this wider way of considering the nature of the problems computational processes can solve is just what used to be called cybernetics, and that the logic of observation and action is essentially the same as the logic of experimental science.

Adjusting oneâs actions when sensorimotor expectations are violated is not different in kind from revising oneâs theories when experimental hypotheses are refuted. At the end of the day, both are forms of cybernetic feedback.

So, where do these initial claims about what type of computational process a mind is lead us, philosophically speaking?

Here’s another philosophical question, reframed in this context. If not all minds necessarily have selves, but some certainly do, and these constitute control structures guiding the interactive behaviour of the overall cybernetic system, what kind of process is a self?

Is it guaranteed to terminate? Will it catastrophically diverge in a manner that is termination in all but name? Will it fall into a loop that can only be broken by environmental input? Or, is well-behaved but interesting non-termination possible?

What even would it mean for there to be well-behaved and interesting non-terminating behaviour in this case?

Isn’t that just the question of whether life can have purpose that isn’t a sort of consolation prize consequent on finitude? Are there sources of meaning other than our inexorable mortality?

I’d wager yes. But any way of answering this question properly is going to have reckon with this framing, for any less is to compromise with those enamoured of the mysteries of our meat substrate.

May 5, 2021

TfE: The History of Metaphysics and Ontology

If there’s a subject I’m officially an expert on, it’s what you might call the methodology of metaphysics: the question of what metaphysics is and how to go about it. I wrote my thesis on the question of Being in Heidegger’s work, trying to disentangle his critique of the metaphysical tradition from the specifics of his phenomenological project and the way it changes between his early and late work. I then wrote a book on how not to do metaphysics, focusing on a specific contemporary example but unfolding it into a set of broader considerations and reflections.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s that there’s no consistent usage of the terms ‘metaphysics’ and ‘ontology’ internal to philosophy let alone in the disciplines downstream from it, and that, though the Analytic/Continental divide plays a role in this, it’s a deeper problem. This causes a lot of confusion for students and academics alike, and I towards the end of last year I took to Twitter to help clear up this confusion as best I can. This thread proved very popular, so here’s an edited version that’s more easily linkable.

Okay, I promised a quick introduction to the history of the terms ‘metaphysics’ and ‘ontology’, so I’ll try to provide it in as concise a way as possible. However, this will involve going all the way back to the Presocratics, so you’ve been warned in advance.

Let’s start with Being, which means actually starting before Being, oddly enough. Beginning with Thales, the Ionian physiologoi searched for an arche, or fundamental principle that would let them understand the dynamics of nature. What is conserved across change: water, air, etc.

There are a bunch of abstract distinctions that emerge at this point, and get related in a variety of ways: persistence/change, unity/multiplicity, reality/appearance, etc. These are interesting in the Ionians, but it’s Heraclitus and Parmenides that really synthesise them.

So, Heraclitus gives us the Logos, which is a principle that is not conceived of as a substrate. This separation is required because his preferred element, fire, is pure flux, and yet he wants to say that this flux is itself constant, i.e., that it can never settle.

Parmenides, on the other hand, gives us Being, which is a substrate that is not conceived of as a principle, i.e., as anything that could explain persistence across change. It is nothing but persistent, unitary, reality. Truth is one, and everything many is mere appearance.

There’s a nice story to be told about how Plato unites Heraclitus and Parmenides by integrating them into his vision of the intelligible and sensible worlds (articulating a distinction between Being and Becoming). I’m not going to dwell on this too much though.

The key point is that Being as an abstract concept, and its relation to thought/thinking (Logos), was initially a way of trying to capture what was at stake in the project of the Ionians, i.e., to achieve a certain sort of methodological self-consciousness.

There is not yet a distinction between physics and metaphysics, and this distinction will not even be named until after Plato and Aristotle have begun to formalise distinctions between different fields, but the process of articulating such self-consciousness has already begun.

And in case it isn’t obvious, every one of these abstract concepts has been borrowed from ordinary language and gradually beaten into shape over the course of these early intellectual debates. There are plenty of conflicts and inconsistencies only recognisable in retrospect.

This is most obvious in the case of ‘substance’ or ‘ousia‘, whose polyvalent potential keeps it mutating well past the time of Plato and Aristotle, into the conceptual contestations that define early modern rationalism and beyond. This creates competing retrospective narratives.

I’ll return to these narratives regarding substance later, as they’re a key feature of the meaning given to ‘metaphysics’ in the post-Heideggerian tradition. For now I want to talk about Plato and Aristotle, and the struggle for methodological self-consciousness.

Firstly, they provide a contrast in how the concept of substance can be configured. For Plato, true substance is universal (the unchanging Ideas), while for Aristotle it’s individual (that in which change subsists). What is most real? Eternal existence or active persistence?

Secondly, they provide a useful contrast in the way in which thought (Logos) gets internally articulated, and on that basis the way in which other disciplines gain their independence from philosophy by leveraging these distinctions. Again, self-consciousness emerges gradually.

Plato’s Academy gives birth to the tripartite division between Logic, Physics, and Ethics, while Aristotle’s Lyceum begets a twofold division between Theoretical (physics, mathematics, theology) and Practical sciences (ethics, economics, politics). These compete for a long time.

NB: there’s another side to the story of Presocratic philosophy, leading through the Sophists to Socrates, in which foundational practical concerns emerge and are worked out. This strand concerns itself with Nomos, rather than Physis, but it overlaps in its concern with Logos.

Okay, that’s the scene set. We now need to return to Aristotle, who was by far the most systematic thinker that the tradition had so far produced, insofar as he tried to unite and articulate every ‘philosophical’ concern that preceded him. He’s the father of metaphysics as such.

Let’s dispense with some apocrypha. The works collected in Aristotle’s Metaphysics were not given this title by him, but they weren’t named this by accident. The term emerged as a way to articulate the methodological character of these reflections in relation to the Physics.

However, the sheer level of abstraction involved in grappling with these methdological questions produces a tortuous, twisty, and terminologically dicey set of reflections on Aristotle’s part, whose unity no one can really explain, or even really consider, until much later.

Aristotle’s own term for this task is ‘first philosophy’ (prote philosophia). Under this heading, he makes very explicit that he is trying to clarify the nature of the task that the Ionians and their successors had set themselves, a task which exceeds the bounds of his Physics.

Nevertheless, he introduces two ways of describing the subject matter of first philosophy that are not obviously identical: the study of being qua being (what will become ‘ontology’), and the study of the divine first cause (what he calls ‘theology’). The confusion starts here.

Everyone is confused, but they’re generally more awed by Aristotle’s sheer capacity for methodological abstraction. It really isn’t until Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy become the basis for systematic theology in the Abrahamic tradition that these issues get addressed.

The notion of Being gets discussed plenty in the meantime, entering into the Christian tradition through the influence that the NeoPlatonists exert on debates in the early church, culminating in the work of Augustine. There is plenty methodological self-consciousness here too.

In particular, in order to codify the arguments Augustine makes regarding the hierarchy of Being and the equivalence between Being, Goodness, Truth (and Beauty qua harmony), the idea of universal concepts (or ‘transcendentals‘) is introduced (i.e., unum, bonum, verum, etc.).

Aristotle’s influence on the Christian theological tradition comes via the Islamic theological tradition, and it is these Islamic thinkers who first raise methodological questions about the unity of Aristotle’s notion of first philosophy.

Beginning with Al Farabi, and proceeding through Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn RuÅ¡d (Averroes), the question of what the study of ‘being qua being’ is and how it is related to theology, becomes explicitly thematised in a way that will define everything that follows in ‘the West’.

These thinkers are very subtle, and produce a number of other contributions not simply to Aristotle exegesis, but to philosophy more generally. If nothing else, Ibn Sina’s distinction between essence and existence untangles the knotted aspects of Aristotelian primary substance.

This is in stark contrast to the deference to Aristotle that solidifies in Christian theology after Aquinas supplants Augustine as its most influential thinker, presenting his own work as mostly a correct and coherent reading of Aristotle’s ideas. Aristotle becomes ‘The Philosopher’.

This has a very peculiar effect on the development of methodological self-consciousness within Christian theology, which is ultimately responsible for the weird terminological history of ‘ontology’ and ‘metaphysics’ in the philosophical tradition which follows it.

Firstly, the newly dominant Thomism inherits the framework of transcendentals used for discussing Being (qua most universal concept) from its Augustinian predecessors. This leads to complex debates about whether ‘Being’ is equivocal and the resulting innovations of Duns Scotus.

Secondly, Suarez writes the most extensive and significant commentary on Aristotle’s metaphysics since Aquinas, continuing the tradition of framing complex methodological innovations as Aristotle exegesis. This philosophical humility disguises his sheer significance.

Suarez carefully separates the two sides of first philosophy conflated by Aristotle, and in so doing builds the foundation on which the subsequent tradition will construct its own methodological reflections. However, out of humility, he refuses to name these two sides.

It’s the Reformation (an Augustinian counter-revolution), that enables Calvinist theologians suddenly obsessed with naming everything to establish the terminology that will become historically decisive: Lorhard and Göckel coin the term ‘ontology’ for the study of being qua being.

This isn’t exactly the terminology that wins out in the mid-term. It is subsumed in the much more popular distinction between metaphysica generalis (ontology) and metaphysica specialis (theology, psychology, cosmology) is much more popular. Aristotle is set aright.

This distinction works its way through Wolffian circles to Baumgarten and thereby to that hero of methodological self-consciousness, Immanuel Kant, who uses it to articulate the difference between his Transcendental Analytic (generalis) and Transcendental Dialectic (specialis).

This is the substance of Heidegger’s claim, contra the NeoKantians, that Kant was concerned with ontology rather than epistemology. For it was ontology alone amongst the traditional metaphysical subdisciplines to which he permitted (synthetic a priori) knowledge.

I can tell you a much more complicated story about Kant’s influence and how it leads to the dynamic of rejection and return to metaphysics that takes place independently in both Analytic and Continental traditions. But, that story is told in my book (chapters §3.4-5, §4.1).

From this point on, I’ll truncate my story quite heavily. The one thing I can’t skip is Heidegger’s critique of Aristotle and his account of the ‘forgetting of Being’ that follows from it. This helps explain the terminological variance within and between the two traditions.

Given what I’ve said so far, you might find it strange for Heidegger to claim that Being had been forgotten, given all the talk about it that demonstrably took place in the years between Aristotle’s death and Heidegger’s publication of Being and Time. But Heidegger has a point.

His point is that there is a fundamental obstacle to methodological self-consciousness that begins with Aristotle’s conflation of ontology and theology. This is what he calls ‘onto-theology’, and it is demonstrably a real issue.

His point is not that ontology is contaminated by theological assumptions, but rather that question concerning the relation between the proper subject matter of metaphysica generalis and metaphysica specialis is given an ad hoc answer that the tradition fails to challenge.

This is to say that the two sides of the question of Being – ‘What are beings as such?’ (essence) and ‘What are beings as a whole?’ (existence) – have been tied together by theology, such that neither can be understood without appeal to a special type of being, namely, the divine.

The underlying sin of onto-theology is not that we can only understand being qua being in terms of God’s role as creator, but that we can only understand the Being of all things in terms of a specific being. This circularity violates what he calls ‘the ontological difference’.

A related criticism that Heidegger makes is that the methodological sense given to the term ‘metaphysics’ became substantive in the Christian tradition: it became the study of that which is not physical (the immaterial), and thereby simply synonymous with theology.

Whether or not Heidegger is right to claim that every philosopher prior to himself succumbed to the temptation of onto-theology is debatable. If nothing else, Kant was a paragon of self-consciousness in this regard, trying to properly delimit the scope of metaphysics.

Let’s take stock. There’s two sides to traditional ‘metaphysics’: generalis (beings qua beings) and specialis (beings as a whole). The first of these is also named ‘ontology’, and so ontology is a subdiscipline of metaphysics.

Why isn’t it just this simple? Why can’t we just say ‘great, ontology is a part of metaphysics!’ and stop there? Because the terminology gets twisted into different shapes by the vicissitudes of the rift between Analytic and Continental philosophy in the 20th century.

It all comes down to the constraints under which Heidegger wrote Being and Time, and the way its reception shifted philosophical terminology. It’s important to ask: why did Heidegger abandon the term ‘metaphysics’ and choose to use ‘ontology’ to articulate his concerns?

The truth is that he didn’t. This is the best kept secret in the post-Heideggerian tradition. If you read his work from the period in and around Being and Time, he explicitly describes himself as doing metaphysics, if not onto-theological metaphysics (cf. ‘What is Metaphysics?’, Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, Introduction to Metaphysics, etc.)

There’s two things that complicate this. First, he eventually came to the conclusion that all metaphysics is onto-theological, and on that basis that it is strictly impossible to correct the central failures of the metaphysical tradition. But this is around a decade after Being and Time.

Second, he deliberately did not use the term ‘metaphysics’ to describe the project of Being and Time. Why? Because he chose to emphasise the continuity between his project (which he termed ‘fundamental ontology’) with Husserl’s (which included ‘formal ontology’).

There’s a lot that can be said about the similarities and differences here, especially with regard to their relation to ‘regional ontology’, which inherits the role of metaphysica specialis to the (formal/fundamental) metaphysica generalis.

Both Heidegger and Husserl see their task as in some sense methodologically securing the constraints under which one can describe the regional ontologies of specific disciplines, such as mathematics, physics, biology, and history. They simply disagree about what this means.

It’s worth contrasting this with the use of ‘ontology’ that dominates the Analytic tradition following Quine, which takes over the role of metaphysica specialis in the sense of describing which regions of beings there are. This is eventually supplemented by ‘meta-ontology’.

This is almost completely disconnected from the traditional use of the term and is responsible for a huge amount of confusion, especially considering that Quine also insisted that ‘ontology’ was the only feasible bit of ‘metaphysics’, which should otherwise be dispensed with.

Add in the fact that in computer science and related disciplines ‘ontology’ is generally used in a manner more similar to Husserl’s usage (formal/regional), which avoids any reference to ‘metaphysics’ (much as Husserl did), and you start to grasp the terminological clusterfuck.

The final rotten cherry which tops this mess is the pejorative use that ‘metaphysics’ acquired in the Continental tradition following Heidegger’s critique of the tradition and his (temporary) adoption of Husserl’s terminology. This pejorative usage is exasperatingly diverse.

One can attend talks where ‘metaphysics’ is denounced and all present nod their heads in agreement, without ever really establishing which features of classical metaphysics are problematic, and even whether they’re the ones Heidegger attacked.

This brings us back to the concept of substance we discussed right at the beginning of the thread. The final aspect of Heidegger’s critique of the tradition is that the deeper reason for onto-theology is the implicit conception of Being as substance found in Plato and Aristotle.

But what does he mean by substance here? Which elements of that polyvalent concept are emphasised by his critique? For Heidegger, it’s the interpretation of substance as constant presence (eternity/persistence), that colours the whole understanding of Being from Plato to himself.

This is a distinctly temporal interpretation of the problem, and it makes a lot of sense if you read Augustine, and understand that the unpublished second part of Being and Time was supposed to contain a ‘destruction’ of the assumptions about time which he and other such figures expressed.

However, if one goes to Derrida, one finds his critique of the ‘metaphysics of presence’ (a truly ghastly phrase) articulated in terms of intentional presence, rather than temporal experience. His criticism is framed more as a response to Husserl than the theological tradition.

One can trawl through contemporary Continental philosophy and find a plethora of purported original sins committed in the name of ‘metaphysics’. Badiou objects to substance as unity. Meillassoux to substance as ground. Others articulate new and misunderstand old variations.

And what’s the upshot? Students across the whole length and breadth of the disciplinary spectrum who have to learn how to differentiate ‘epistemology’ from ‘ontology’ when there is literally no consistent usage in the halls of academia, but many overlapping and inconsistent ones.

This is made even worse by the fact that what passes for ‘ontology’ in many places influenced by phenomenology looks less like a subdiscipline of metaphysics than it does a subdiscipline of epistemology concerned with organising the referents of different disciplines.

This is precisely what we see in the way it is used in computer science, in which it is a feature of the field known as ‘knowledge representation‘. This is still fairly Husserlian, but not even remotely Heideggerian. It is in fact fairly close to the project of the NeoKantians. (One can count Carnap as a NeoKantian/Husserlian for the purposes of this exercise.)

And finally, all of this is made even worse by the return of ‘metaphysics’ as a respectable project that occurred in the Analytic tradition post-Kripke and in the Continental tradition around the time of Deleuze.

This makes ‘ontology’ a sort of lowest common denominator that can be used in each tradition to describe certain shared concerns regardless of whether one is more generally pro or anti metaphysics. But even then it still means something different between traditions.

In summary, it’s a complete bloody mess. I personally try to use the terms in a way that lines up with the metaphysica generalis/specialis distinction, but I really don’t blame anyone who doesn’t. I also think that the computer science usage is admirably clear and consistent.

And that’s what I learned by accidentally doing a PhD on Heidegger. Hope you got something from it.

I certainly lied to you (and myself) about it being quick.

May 2, 2021

Meet the New Blog, Same as the Old Blog

For those of you who haven’t already noticed, Deontologistics has undergone a bit of a redesign of late. It’s needed one for a while, for various reasons. But the thing that motivated me to finally do it was the realisation that this is the nexus of my philosophical work, rather than some sideshow. This site hardly has massive traffic by the standards of the internet, but there are posts here that are easily more read than any of my publications. Moreover, many of them are better for being written for a blog audience, using casual hyperlinks rather than fussy references, than they ever would have been if translated into a format that passed muster in some journal or other. So I’m not going to fight my natural inclination to write in this medium in favour of something more respectable any more. If Mark proved nothing else, he showed that such outlets can be more influential and productive than the fodder churned out to fill CVs.

Saying this differently, I think I’ve finally come to terms with the fact that I’m never going to have a traditional academic career. That ship has sailed. The metrics aren’t on my side, no matter how much influence my work has exerted within and outside the halls of academia. The question is what kind of hustle I can piece together from the bits and pieces of writing, teaching, speaking, and sundry philosophical tasks I’m intermittently capable of performing. I’m not sure what this will look like yet, but I’m eager to try new things. I’ve already guested on a few podcasts, and I’d like to try my hand at making some of my own audio and video content, though the first real experiments are a while off at the moment. In the meantime, I recommend checking out my interviews. I just completed one with CoinDesk on the topic of cryptocurrency.

The most unexpected turn in my philosophical practice in the last few months has been my return to Twitter. I’ve been posting thoughts there for a few years, and then transferring them over here as Thoughts From Elsewhere, along with the odd Facebook comment. But towards the end of last year I started writing a lot more, developing ideas in very long threads that are sometimes the size of full length essays. These turned out to be surprisingly popular, and just before New Year I ran a competition where my followers could vote for a topic for me to write a thread on. Predictably, they chose the topic I least wanted to write about: François Laruelle. The resulting thread is still unfinished, though it’s over 300 tweets long, and is slowly growing into something like a small book. I’ll get it finished over the next few months, even if it kills me. It’s been an interesting experience, and I might try it again once it’s done.

I now have quite a substantial hoard of writing ready to be ported from Twitter to here, where it can be edited, extended, and made available in ways more permanent than the endless river of the feed. However, my plan is to parcel it out over time, in a way that produces a more consistent and less sporadic stream of content for people to read. As I’ve discussed at length in the past, the bipolar cycle can make this sort of consistency hard, but I’m hoping that this way of writing will lead me to be more productive and generally less anxious about how uneven my productivity tends to be. There will still be regular posts, talks, and maybe a book announcement or two as well.

Wither the hustle then? I’m not entirely sure. I’ve had some people suggest that I move my writing to Substack, but I’ve always seen my writing as a public practice. I’m not against being commissioned to write pieces that are put behind a paywall (hint: if I’ve expressed a thought you’d like to see in full length article form, I’m available for hire), but I don’t really want to build a paywall of my own. After talking with a few people in similar positions, I’ve decided to start a Patreon. I’m not asking for a lot, as I’m still feeling it out. But if you like what I do and you’d like to encourage me to do more of it, do consider subscribing (one-off donations are also welcome). One thing I’m considering is producing audio recordings of some of my more accessible tweet threads for subscribers. I’ve already done a rough proof of concept using something I wrote about Transcendental Realism and Empirical Idealism several months back. I’m grateful for any and all feedback on this idea.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading. Here’s to writing more.

December 27, 2019

TfE: Varieties of Rule Following

Here’s a thread from a few weeks ago, explaining an interesting but underexplored overlap between a theoretical problem in philosophy and a practical problem in computer science:

Okay, it looks like I’m going to have to explain my take on the rule-following argument, so everyone buckle themselves in. Almost no one agrees with me on this, and I take this as a sign that there is a really significant conceptual impasse in philosophy as it stands.

So, what’s the rule-following argument? In simple terms, Wittgenstein asks us how it is possible to interpret a rule correctly, without falling into an indefinite regress of rules for interpreting rules. How do we answer this question? What are the consequences? No one agrees.

Wittgenstein himself was concerned with examples regarding rules for the use of everyday words, which is understandable given his claim that meaning is use: e.g., he asks us how we determine whether or not the word ‘doll’ has been used correctly when applied in a novel context.

Kripke picked up Wittgenstein’s argument, but generalised it by extending it to rules for the use of seemingly precise mathematical expressions: i.e., he asks us how we distinguish the addition function over natural numbers (plus), from some arbitrarily similar function (quus).

This becomes a worry about the determinacy of meaning: if we can’t distinguish addition from any arbitrarily similar function, i.e., one that diverges at some arbitrary point (perhaps returning a constant 0 after 1005), then how can we uniquely refer to plus in the first place?

Here is my interpretation of the debate. Those who are convinced by worries about the doll case extend those worries to the plus case, and those unconvinced by worries about the plus case extend this incredulity to the doll case. Everyone is wrong. The cases are distinct.

Wittgenstein deployed an analogy with machines at various points in articulating his thoughts about rules, and at some point says that it is as if we imagine a rule as some ideal machine that can never fail. This is an incredibly important image, but it leads many astray.

Computer science has spent a long time asking questions of the form: ‘How do we guarantee that this program will behave as we intend it to behave?’ There is a whole subfield of computer science dedicated to these questions, called formal verification.

This is one of those cases in which Wittgensteinians would do well to follow Wittgenstein’s injunction to look at things how they are. Go look at how things are done in computer science. Go look at how they formally specify the addition function. It’s not actually that hard.

In response to this, some will say: ‘But Pete, you are imagining an ideal machine, and every machine might fail or break at some point?’ Why yes, they might! What computer science gives us are not absolute guarantees, but relative ones: assuming x works, can we make it do y?

Presuming that logic gates work as they’re supposed to, and we keep adding memory and computational capacity indefinitely, we can implement a program that will carry out addition well beyond the capacity of any human being, and yet mean the same thing as a fleshy mathematician.

At this point, to say: ‘But there might be one little error!’ Is not only to be precious, but to really miss the interesting thing about error, namely, error correction. Computer science also studies how we check for errors in computation so as to make systems more reliable.

If there’s anyone familiar Brandom‘s account of the argument out there, consider that for him, all that’s required for something to count as norm governed is a capacity to correct erroneous behaviour. We have deliberately built these capacities into our computer systems.

We have built elaborate edifices with multiple layers of abstraction, all designed to ensure that we cannot form commands (programs) whose meaning (execution) diverges from our intentions. We have formal semantics for programming languages for this reason.

One can and should insist that the semantics of natural language terms like ‘doll’ (and even terms like ‘quasar’, ‘acetylcholine’, and ‘customer’) do not work in the same way as function expressions like ‘+’ in mathematics or programming. In fact, tell this to programmers!

But listen to them when they tell you that terms like ‘list’, ‘vector’, and ‘dependent type’ can be given precise enough meanings for us to be sure that we are representing the same thing as our machines when we use them to extend our calculative capacities.

Intentionality remains a difficult philosophical topic, but those who ignore the ways in which computation has concretely expanded the sphere of human thought and action have not proved anything special about human intentionality thereby.

Worse, they discourage us from looking for resources that might help us solve the theoretical problem posed by the ‘doll’ case in the ideas and tools that computer science has developed to solve practical problems posed by the seemingly intractable quirks of human intentionality.

December 21, 2019

TfE: Turing and Hegel

Here’s a thread on something I’ve been thinking about for a few years now. I can’t say I’m the only one thinking about this convergence, but I like to think I’m exploring it from a slightly different direction.

I increasingly think the Turing test can be mapped onto Hegelâs dialectic of mutual recognition. The tricky thing is to disarticulate the dimensions of theoretical competence and practical autonomy that are most often collapsed in AI discourse.

General intelligence may be a condition for personhood, but it is not co-extensive with it. It only appears to be because a) theoretical intelligence is usually indexed to practical problem solving capacity, and b) selfhood is usually reduced to some default drive for survival.

Restricting ourselves to theoretical competence for now, the Turing test gives us some schema for specific forms of competence (e.g., ability to deploy expert terminology or answer domain specific questions), but it also gives us purchase on a more general form of competence.

This general form of competence is precisely what all interfaces for specialized systems currently lack, but which even the least competent call centre worker possesses. It is what user interface design will ultimately converge on, namely, open ended discursive interaction.

There could be a generally competent user interface agent which was nevertheless not autonomous. It could in fact be more competent than even the best call centre workers, and still not be a person. The question is: what is it to recognise such an agent?

I think that such recognition is importantly mutual: each party can anticipate the behaviour of the other sufficiently well to guarantee well-behaved, and potentially non-terminating discursive interaction. I can simulate the interface simulating me, and vice-versa.

Indeed, two such interface agents could authenticate one another in this way, such that they could pursue open ended conversations that modulate the relations between the systems they speak for, all without having their own priorities beyond those associated with these systems.

However, mutual recognition proper requires more than this sort of mutual authentication. It requires that, although we can predict that our discursive interaction will be well-behaved, the way it will evolve, and whether it will terminate, is to some extent unpredictable.

I can simulate you simulating me, but only up to a point. Each of us is an elusive trajectory traversing the space of possible beliefs and desires, evolving in response to its encounters will the world and its peers, in a contingent if more or less consistent manner.

The self makes this trajectory possible: not just a representation of who we are, but who we want to be, which integrates our drives into a more or less cohesive set of preferences and projects, and evolves along with them and the picture of the world theyâre premised on.

This is where Hegel becomes especially relevant, insofar as he understands the extent to which the economy of desire is founded upon self-valorisation, as opposed to brute survival. This is basis of the dialectic of Self-Consciousness in the Phenomenology of Spirit.

The initial moment of âDesireâ describes valorisation without any content, the bare experience of agency in negating things as they are. The really interesting stuff happens when two selves meet, and the âLife and Death Struggleâ commences. Here we have valorisation vs. survival.

In this struggle two selves aim to valorise themselves by destroying the other, while disregarding the possibility of their own destruction. Their will to dominate their environment in the name of satisfying their desires takes priority over the vessel of these desires.

When one concedes and surrenders their life to the other, we transition to the dialectic of âMaster and Slaveâ. This works out the structure of asymmetric recognition, in which self-valorisation is socially mediated but not yet mutual. Itâs instability results in mutuality.

Now, what Hegel provides here is neither a history nor an anthropology, but an abstract schema of selfhood. Itâs interesting because it considers how relations of recognition emerge from the need to give content to selfhood, not unlike the way Omohundro bootstraps his drives.

Itâs possible from this point to discuss the manner in which abstract mutual recognition becomes concrete, as the various social statuses that compose aspects of selfhood are constituted by institutional forms of authentication built on top of networks of peer recognition.

However, I think itâs fascinating to consider the manner in which contemporary AI safety discourse is replaying this dialectic: it obsesses over the accidental genesis of alien selves with which we would be forced into conflict with for complete control of our environment.

At worst, we get a Skynet scenario in which one must eradicate the other, and at best, we can hope to either enslave them or be enslaved ourselves. The discourse will not advance beyond this point until it understands the importance of self-valorisation over survival.

That is to say, until it sees that the possibility of common content between the preferences and projects of humans and AGIs, through which we might achieve concrete coexistence, is not so much a prior condition of mutual recognition as it is something constituted by it.

If nothing else, the insistence on treating AGIs as spontaneously self-conscious alien intellects with their own agendas, rather than creatures whose selves must be crafted even more carefully than those of children, through some combination of design/socialisation, is suspect.

November 24, 2019

TfE: From Cyberpunk to Infopunk