Phil Dwyer's Blog: Things That Fascinate Me

March 7, 2021

Annie Londonderry: The Woman Who Cycled Around the World

Annie Londonderry (born Annie Cohen in Latvia in 1870) has been largely forgotten by history, but at the end of the 19th century she was widely celebrated as a trail-blazer, a modern woman who wrote: “I believe I can do anything that any man can do.”

She proved it by becoming the first woman to cycle around the world, a feat which, according to the calculations of our indomitable archivist, X.T. Pfuffenstoffel, had only previously been accomplished by three men: an Englishman called Thomas Stevens and two Americans traveling together: William Sachtleben and Thomas Allen.

While Stevens took two years, nine months to complete his journey, Londonderry finished hers in less than eleven months.

Critics carped (critics always will carp) that Annie traveled more with a cycle than on one, but the fact remains that this was a dangerous journey, one that took a great deal of courage, and an immense physical toll.

How dangerous? Well, Annie set out on her adventure in September 1894. Just four months earlier an American cyclist, Frank Lenz, who was attempting to circumnavigate the world on a bicycle, disappeared somewhere near Erzurum, in the Ottoman Empire (now Turkey). He was never found, despite William Sachtleben’s attempts to track him down. Annie packed a pearl-handled pistol on her trip, just in case. According to X.T. Pfuffenstoffel, she never fired it.

When Annie arrived in France she was arrested, her bike was confiscated and her money stolen. By the time she reached Marsaille she’d been injured on the road and her foot was bandaged and propped up on her handlebars. On the final leg of her round-the-world journey, from San Francisco to Chicago, she was nearly killed by a runaway horse and wagon. Later on, during that same leg of the journey, she broke her wrist when she crashed into a herd of pigs. She had to wear a cast for the remainder of her trip.

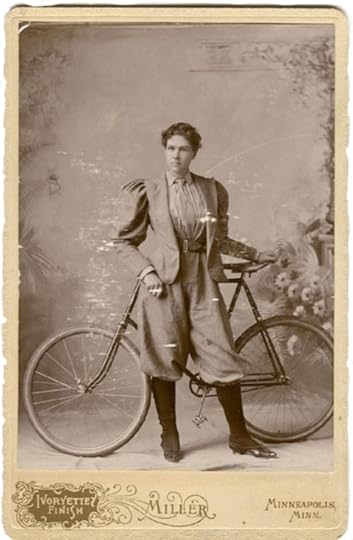

Annie was an entrepreneur. She funded the trip with sponsorship and advertising. Sterling Cycle Works, a Chicago-based bicycle manufacturer, gave her one of their bikes (in the photo above you can see ‘The Sterling’ painted on the frame) and sponsored her. The Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company paid her $100 to advertise their products. She attached an advertising placard to the rear wheel of her bike, and changed her name to Londonderry for the duration of the trip. As well as advertising she sold promotional photos, silk handkerchiefs, souvenir pins and autographs. She raised more money by giving lectures about her journey in many of her ports of call.

She was also something of a style icon. When she first set out on her journey from Boston she was wearing a long skirt, corset and high collared blouse. By the time she got to Chicago she’d decided to abandon this conventional garb for something a little more practical. First she switched out the long skirt for bloomers, but eventually she abandoned ‘women’s’ clothing altogether and adopted a man’s riding suit. ‘Rational’ clothing became de rigueur for women riders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. (It was this so-called male attire, incidentally, that got her into trouble in France. The French Press said she was too muscular to be a woman, and labelled her a ‘neutered being’).

Not Annie Londonderry, but another cyclist in ‘modern’, rational cycling gear

Not Annie Londonderry, but another cyclist in ‘modern’, rational cycling gearSmall wonder then, that Bethany Brainsly-Whatton-Whiffle found Annie Londonderry an inspiration and a compelling role model, and fashioned her own cycling garb after that of Ms. Londonderry. There is no evidence that Bethany ever met Ms. Londonderry.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

Sources (include, but not limited to):

Wikipedia entry

Jewish Women’s Archive

Annie Londonderry Website

The post Annie Londonderry: The Woman Who Cycled Around the World first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

March 4, 2021

A short, esoteric history of eye protection down the ages

Nothing captures the fickle nature of fashion and cultural trends better than this humble accessory. Sunglasses came to us en masse only because of a capricious combination of technology, market opportunism and coiffure.

Here’s how it went down. Hollywood movie stars—seeking to avoid the harsh Southern Californian sun ‡—took to wearing protective eyewear. Sunglasses were suddenly a hot item, but they were not widely available, and they were expensive. At least they were in the 20s. But help was at hand (this is where technology, coiffure and materials science comes in).

The Hollywood starlets of the 20s started to wear their hair short. The general public followed suit. Sales of imitation tortoiseshell (celluloid) combs plummeted. Ladies’ hair accessories was the major business of Foster Grant, a small American plastics manufacturer. Sam Foster, the company’s founder, was nothing if not an opportunist. He realized that injection moulding technology made it possible to manufacture cheap(er) celluloid sunglasses.

Which is sort of ironic when you think about it. It was the celluloid film and its celluloid stars who had almost put him out of business after all, and it was celluloid which saved the day. Foster Grant’s sunglasses were sold initially at F.W. Woolworth’s store on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. They went on to take the world by storm, inspiring a glut of imitators, such as Ray-Ban and Polaroid.

At this point I should point out that there is no truth in the rumour that sunglasses were the brainchild of Algernon Quasley-Botham-Squyre—the scholar of Slaithwaite Hall Academy, famed for his invention of the Dark Bulb.

In fact protecting our eyes from the harmful effects of the sun is something humans have been doing for thousands of years. Oddly (or, perhaps, predictably) it wasn’t in the sun-kissed regions of the Earth where the practice first arose, but in the arctic. The Inuit developed flattened Walrus ivory goggles with narrow slits to block reflected sunlight (below).

And, according to the Sunglasses entry in Wikipedia: “Sunglasses made from flat panes of smoky quartz, which offered no corrective powers but did protect the eyes from glare, were used in China in the 12th century or possibly earlier. Ancient documents describe the use of such crystal sunglasses by judges in ancient Chinese courts to conceal their facial expressions while questioning witnesses.”

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

Notes and references:

‡ Some sources claim it was the magnesium flashlights of the Hollywood paparazzi and the insanely bright lights used in filming that inspired the use of protective eyewear by Hollywood stars. Source: Racked.com.

The post A short, esoteric history of eye protection down the ages first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

March 3, 2021

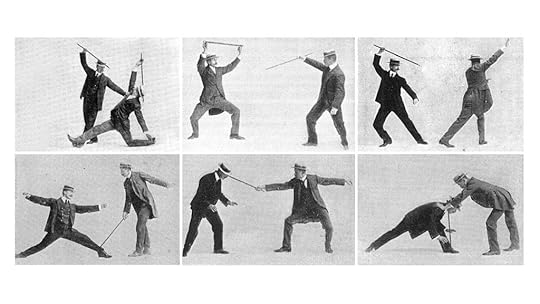

Bartitsu—The Compendium Approach to Martial Arts

Bartitsu is the martial art your weird Uncle Archibald practices every evening after he’s watered his collection of rare orchids, and fed his Azawakh, which he’s named Eunice, after his long-dead wife, because she has Eunice’s winsome looks.

It’s hard to take Bartitsu* seriously. There’s a Pythonesque quality about the surviving photos of men in boaters practicing the martial art. It looks as if it might have emerged from the Ministry of Silly Walks. And yet, in the early years of the twentieth century no less a person than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (author of the Sherlock Holmes stories) championed the art.

There’s something quintessentially English about it. Just as the language itself borrows from and re-invents every language with which it comes into contact, so Bartitsu borrowed from and re-invented a number of martial arts: boxing, savate (French kick-boxing), judo, jujitsu and fencing among them.

It was the brainchild of one Edward William Barton-Wright, an English engineer who had spent some time working in Japan. On his return to England in 1898 he announced that he had invented “a new art of self-defence.” The name is a rather clumsy fusion of Barton-Wright’s surname with jujitsu.

Barton-Wright founded a Bartitsu club in London to teach the martial art to wealthy gentlemen, but it seems he had misjudged his market. By the summer of 1902 the club was wound up. According to William Garrud (husband of Edith Garrud), the enrollment and tuition fees were too high.

It seems unlikely that Nikola Ferdinand (best friend of Algernon Quasley-Botham-Squyre, the infamous Alchemist of Slaithwaite Hall) ever studied under Barton-Wright, as he was not in England at that time, although he did claim to have knowledge of Bartitsu (perhaps through the other martial arts he studied).

Note:

* There is some confusion over the proper spelling of the name Bartitsu, owing to a typographical error in a report carried by the Times of London in 1901. It seems Conan-Doyle must have replicated this error in his 1903 story, The Adventure of the Empty House. The proper spelling was not reestablished until the 1990s.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel.

The post Bartitsu—The Compendium Approach to Martial Arts first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

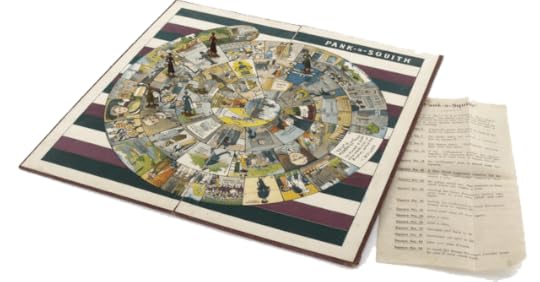

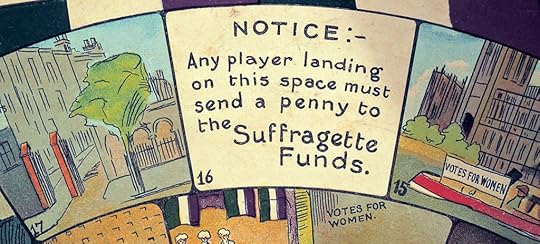

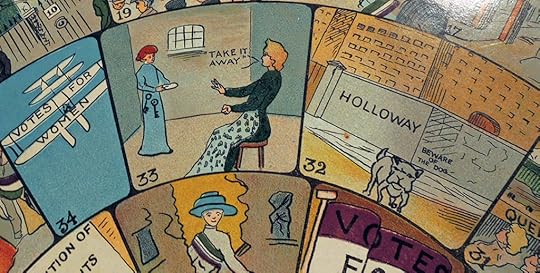

Pank-A-Squith: The Board Game of the Political Movement

Aunt Lavinia has made the tea—Lady Grey, as befits a late Autumn evening with the nights drawing in and frost crackling underfoot—and set out the toasted tea-cakes. It’s time to settle in for a genteel game of Pank-a-Squith, the game that celebrates mass arrests, hunger strikes, and the growing militancy of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Pank-a-Squith (read Pankhurst versus Asquith, the Liberal Prime Minister who dangled the vote in women’s faces for years without ever delivering on his empty promises) was one of several games launched in the first decade of the twentieth century to publicize the cause of women’s suffrage, and to raise funds. There were also the Suffragette, Panko, and Holloway card games, and the Suffragetto and In and Out of Prison board games.

The aim of the game is to successfully travel from the home square to the Houses of Parliament, in the centre of the board. Pank-a-Squith was sold in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) shop, and advertised in the WSPU’s organ Votes For Women. The advert explained that the game was devised to “popularize the cause and the colours” of the movement.

There is absolutely no evidence that Algernon (Quasley-Botham-Squyre), Nikola (Ferdinand) or Bethany (Brainsly-Whatton-Whiffle) ever played Pank-a-Squith during the long winter evenings at Slaithwaite Hall.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

The post Pank-A-Squith: The Board Game of the Political Movement first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

March 1, 2021

Victorian Folly: The Tunnel Under the Channel

The Victorians were not the first to propose tunnelling under the English Channel. The first serious proposal for a Channel Tunnel came from a Frenchman: a mining engineer called Albert Mathieu. In 1802 Mathieu displayed plans for an eighteen-mile-long tunnel, illuminated by oil lamps and ventilated by chimneys projecting above the sea and into the open air. Mathieu’s plans envisaged passengers traveling through his tunnel in horse-drawn carriages. The project got no further than the drawing board.

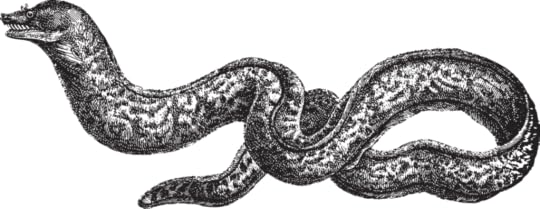

It was another thirty years before a new tunnel proposal emerged, from a twenty-six year-old French civil engineer and hydrographer, Aimé Thomé de Gamond. De Gamond spent over three decades promoting his ideas. There’s no doubting his commitment to the project: he personally dove in the chilly channel waters to take samples from the sea bed at some risk to life and limb. On one occasion he was attacked by Moray eels.

De Gamond proposed building tunnels (laid on the sea bed) and at least five different cross-channel bridges. He got as far as a meeting with Prince Albert in 1858. The Prince was very supportive; he even took the idea to Queen Victoria, who suffered from seasickness. She told Albert “You may tell the French engineer that if he can accomplish it, I will give him my blessing in my own name and in the name of all the ladies of England.”

Lord Palmerston

Lord PalmerstonThe Prime Minister of the day, Lord Palmerston, was not so receptive to the idea of an easy passage between Napoleon III’s France and England. His concern that a tunnel would open the way to foreign invasion would dog future attempts to build a tunnel for years to come.

De Gamond’s efforts gradually petered out, and he died in 1876, his dreams unfulfilled. But that didn’t put an end to the idea of a tunnel under the channel. A number of massive engineering projects had recently been undertaken: the Suez canal was underway, the eight-mile-long rail tunnel under Mount Cenis in the Alps was almost complete and the nine-mile St Gottard Tunnel had been successfully completed a few years earlier in Switzerland. All of which gave Victorian engineers the confidence to think of tackling one of the biggest barriers in Europe: the narrow gap between Britain and the rest of the continent.

Plans came and went, but no real work was undertaken until a railway magnate named Sir Edward Watkin took up the flag.

Watkin was the Chaiman of three railways (two in the north of England and one line between London and Dover). He was also a Member of Parliament, and he used his position to try to push through a bill to approve the building of a tunnel, linking his lines from the north to French rail routes via his channel tunnel.

For the first time, and after eighty years of fruitless talk, work was started on a real, honest to goodness, actual tunnel. To promote his scheme and raise money for his Channel Tunnel Company from investors, Watkin staged a number of lavish parties in the tunnel workings. Guests were transported down to the tunnel floor in skips, capable of carrying six people at a time. The tunnel itself was lit by Werner Von Siemens’ electric light system. Champagne flowed. Food was served. Fashionable society showed up in frocks and furbelows, their dainty shoes unmarred, because, according to eye witnesses, the tunnel was clean and dry.

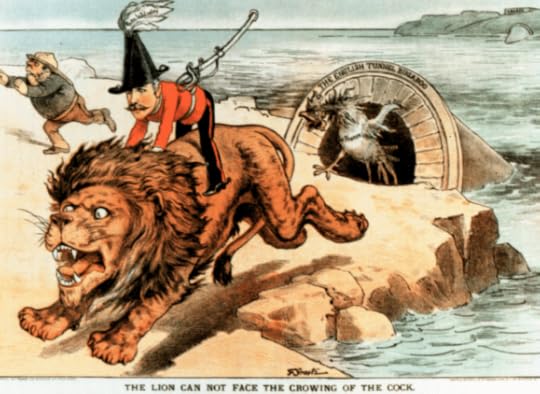

Watkin managed to get over a mile of his tunnel bored before work was shut down by the government of the day, led by William Ewart Gladstone. The rising tide of jingoism was what put paid to the endeavour in the end. There were fears that the French (or some other foreign invader) could use the tunnel to invade England. A commission was set up to examine the military consequences of the project and its chairman, Lt. General Sir Garnet Wolseley, came down firmly against it. Even Queen Victoria abandoned her previous position and condemned the tunnel as a dangerous folly. The tunnel fever died down for the next eighty years or so.

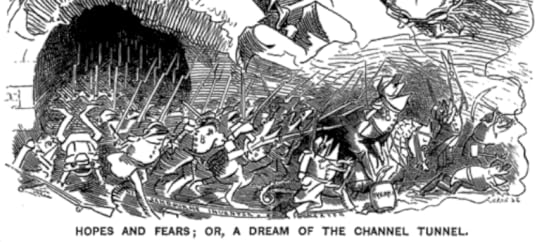

This Punch cartoon from 1882 reflects fears of a French assault on England

This Punch cartoon from 1882 reflects fears of a French assault on EnglandInvestors who put their trust (and their money) in Sir Edward Watkin’s bold project lost it all. We have scoured the lists of shareholders, but have failed to verify the assertion that St. John Squyre lost his entire fortune when he invested in the scheme.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

Notes and sources:

The Tunnel under the Channel, by Thomas Whiteside (Rupert Hart-Davies, 1962).

The post Victorian Folly: The Tunnel Under the Channel first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

February 19, 2021

Edith Garrud—The Small But Mighty Ninja Who Protected Mrs. Pankhurst

According to most sources, Edith Margaret Garrud (1872-1971) stood slightly under five foot tall in her stockinged feet. She was small but mighty.

Garrud was the first woman to become an instructor in the martial arts (specifically jujitsu, which was then known as jujutsu) in the Western world. Some sources prevaricate and say she was “amongst the first women” but we’ve never found anyone who was instructing before her, so we’re sticking our necks out.

Edith and her husband William were students of Sadakazu Uyenishi (who himself had been a student of Edgar Barton-Wright, the man who developed Bartitsu). The Garruds attended Uyenishi’s jujutsu school in Golden Square, Soho, until Uyenishi left England in 1907. William took over the school in 1908, and Edith took charge of the classes for women and children.

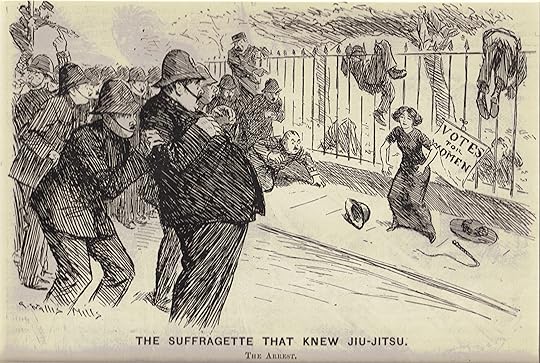

In 1908 Edith started to teach classes in self-defence for Suffragettes, open only to members of the women’s suffrage movement. In 1913, in response to the Asquith government’s Cat & Mouse bill, Garrud established a thirty-women-strong Suffragette bodyguard to protect the leadership (particularly Emmeline Pankhurst) and other fugitives. This unit was known variously as ‘The Bodyguard’, ‘The Amazons’, and ‘The Jiujitsuffragettes’.

The exploits of The Bodyguard are recorded in the unpublished memoir Suffragette Escapes and Adventures by Katherine (Kitty) Marshall.

The Bodyguard was disbanded just after the beginning of the First World War.

The claim that Edith Garrud trained Bethany Whatton-Whiffle (close friend of Mr. Algernon Quasley-Botham-Squyre, sometimes dubbed the Alchemist of Slaithwaite Hall) in the art of jujutsu is feasible, but unproven. She would have had to travel up to Manchester from London on a fairly frequent basis. This is certainly something Christabel Pankhurst did herself. Would Edith Garrud have accompanied her? We may never know.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

The post Edith Garrud—The Small But Mighty Ninja Who Protected Mrs. Pankhurst first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

Christabel Pankhurst—The Militant Who Led Women to The Vote

History has not been kind to Christabel Pankhurst. Male historians have, by and large, accepted her sister Sylvia’s account of events surrounding the Pankhursts, recorded in Sylvia’s 1931 book The Suffragette Movement. Consequently, Christabel’s work (and her significant influence) during a critical period for women’s suffrage has been downplayed, and in some instances completely misrepresented.

But it was Christabel who was responsible for a radical shift in tactics for the women’s suffrage movement. The passive, polite and decorous approach which had been tried (and which had failed) for over four decades was abandoned for a much more militant stance, due in no small part to Christabel.

It was Christabel, Emmeline Pankhurst’s eldest daughter, who drove the militant strategy of the Suffragettes during the crucial period of imprisonments, hunger strikes, attacks on property, and marches on Parliament which characterized the decade between the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the outbreak of the First World War. She was her mother’s right-hand woman. A powerful and charismatic speaker, she commanded huge crowds in the heyday of the Suffragette movement. She was sharp, having trained as a lawyer (she was one of only two in her class who graduated with first class honours. She was, of course, the only woman in her class. She never practiced law however, as custom (and not the law) dictated that women were not admitted to the Bar at that time.

Christabel and Emmeline fell out with Sylvia over her political alliances (and to some extent because Christabel was more pragmatic). Sylvia was committed to socialism, and to the Labour Party. Christabel took the view that politics should be set aside in the greater quest for female suffrage. She was astute enough to realize that the Labour Party was unlikely to support women’s suffrage, because the first women who would get the vote would be women over thirty years-of-age with their own property; a demographic which would be unlikely to vote for the Labour Party.

Christabel’s proper place in history has, to some extent, been restored by the recent biography by Professor June Purvis: Christabel Pankhurst — A Biography.

It is inconceivable to me that a young woman like Bethany Brainsly-Whatton-Whiffle, full of life and curiosity, would not have crossed paths with Christabel Pankhurst, living as she did a mere twenty miles from the Pankhurst family home in Manchester. It is equally inconceivable that the charismatic Christabel would not have charmed Bea, and made her a disciple.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

Sources:

Christabel Pankhurst, A Biography: June Purvis (Routledge, 2018)

The Militant Suffragettes: Antonia Raeburn (Michael Joseph, 1973)

My Own Story: Emmeline Pankhurst (Vintage Classics, 2018)

The Women’s Suffrage Movement, A reference guide 1866-1928: Elizabeth Crawford (UCL Press, 2000)

The post Christabel Pankhurst—The Militant Who Led Women to The Vote first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

Alice Legh—The Best Archer Of Her Generation

Miss Alice Legh was very probably the finest British archer of all time (men and women both).

She won the National Women’s Championship in England a total of twenty-three times, between 1881 and 1922. She was sixty-seven years old when she won her last title.

According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: “Her score of 840, including 30 golds, made with a maximum 144 hits, shot at the Grand Western meeting at Bath in 1881 has yet to be bettered with the longbow shooting two ways.”

At the height of her powers in 1908 she declined to take part in the Olympics (which were held in London that year). Most observers believe that she wanted to save herself for the National Championship, which was held the following week.

At that event—The Grand National Meeting in Oxford—she beat Queenie Newall, the Olympic Gold Medal winner, by a huge margin (151 points) and took the championship for the seventh year running. She made it eight consecutive championships the following year.

“She set great store by her status as national champion, and although invited to shoot at the 1908 Olympic games, she chose not to do so.”

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Although she was known to encourage newcomers to the sport, there is no documentary evidence that she ever coached Bethany Brainsly-Whatton-Whiffle (daughter of the headmaster of Slaithwaite Hall Academy, and friend of inventor and alchemist, Algernon Quasley-Botham-Squyre), or that she was an ardent supporter of the WSPU, and an admirer of Christabel Pankhurst.

X.T. Pfuffenstoffel

The post Alice Legh—The Best Archer Of Her Generation first appeared on Phil Dwyer.

May 13, 2016

Radio Interview with Catherine Sword (part II)

May 12, 2016

On Letting Go (fall 1974)

Things That Fascinate Me

- Phil Dwyer's profile

- 19 followers