Abby Covert's Blog

November 13, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Collaboration

You can see the mess. You’ve even got the imagination to fix it. But somehow, you can’t seem to get anyone else on board with making it better.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. As sensemakers, we have a special knack for spotting chaos in systems, language, and structure. But having the vision to fix something and having the power to make it happen are two very different things.

This guide is about closing that gap. It’s about understanding what collaboration actually means when you’re the one pushing for change, and how to work with others when they hold the keys to making it real.

This article covers:

What does Collaboration mean in Sensemaking?Collaboration in sensemaking isn’t just “working together.” It’s about finding the people who can actually help you move your ideas forward and figuring out how to align your efforts with theirs.

Think of it this way: as a sensemaker, you’re often the cart looking for a horse. You’ve got a useful load to carry—your ideas, your vision for better structure, your plans to fix the mess. But without someone else’s momentum to hitch yourself to, you’re just sitting there waiting to be useful.

Real collaboration means:

Finding alignment, not just agreement. Someone can nod along with your idea and still never help you ship it. You need people whose goals match yours, not just people who think your ideas sound nice.Understanding power dynamics. You might see the problem clearly, but if you don’t have the power to fix it and the people who do have different goals, collaboration becomes nearly impossible.Accepting that timing matters. Sometimes the best collaboration happens when you wait for the right moment, when someone else’s needs finally match what you’ve been trying to do all along.Collaboration in sensemaking is less about convincing people and more about understanding what drives them, then finding the overlap between what you want to fix and what they need to achieve.

Reasons to CollaborateYou might be wondering: why even bother collaborating? Can’t I just fix things on my own?

Sometimes, yes. But most of the time, collaboration isn’t optional. Here’s why:

You don’t have the power to make changes alone. If someone else controls the budget, the team, the timeline, or the final decision, you need them on board. No amount of good ideas can replace actual decision-making power.Different people have different knowledge. You might understand the information structure, but someone else knows the business goals, the technical limits, or the customer needs. Collaboration helps you build a complete picture.Change is harder to undo when multiple people support it. When you collaborate well, you create buy-in. That makes your work stick instead of getting rolled back the moment you move on to something else.You need resources you don’t control. Time, money, people, tools, all of these often belong to someone else. Collaboration is how you get access to what you need.Some problems are too big for one person. Even if you have the power to fix something small, bigger messes require multiple perspectives and skill sets to solve.The bottom line: collaboration multiplies your impact. You might have the vision, but you need other people’s resources, power, and knowledge to make it real.

Common Use Cases for CollaborationSo when should you actively seek out collaboration? Here are the situations where it matters most:

Redesigning navigation or structure across a product.

This touches design, engineering, product management, and often marketing. You’ll need all of them to make it happen.

Creating or updating a language system.

Whether it’s a content style guide, a taxonomy, or just standardizing terms across teams, language change requires coordination across everyone who uses those words.

Fixing technical debt in information architecture.

The mess might be obvious to you, but engineering owns the work to fix it. You need their time and priority, which means you need to understand what drives their decisions.

Launching a new feature or product.

This is collaboration by default. You’re working with a team from the start, and your job is to make sure the information structure supports what everyone else is building.

Responding to outside forces.

New laws, changing user needs, business pivots, these often create the pressure you need to finally fix problems that have been sitting around forever. Use that moment to collaborate when everyone’s incentives align.

Scaling systems across teams.

What works for one team might not work for another. Collaboration helps you understand different needs and build systems that serve everyone.

Post-merger integration.

When companies combine, the clash of different systems, language, and structure becomes impossible to ignore. This is prime collaboration territory, even though it’s messy.

Not all collaboration looks the same. Understanding the different types helps you pick the right approach for your situation.

Partnership collaboration.

This is when you and someone else share power and decision-making. You’re equals working toward the same goal. This works best when you both have similar levels of authority and aligned incentives.

Support collaboration.

Someone else is driving the work, and you’re helping them succeed. Your role is to provide expertise, feedback, or resources they need. This is common when you’re a specialist or an internal expert being pulled into someone else’s project.

Leadership collaboration.

You’re driving the work, and others are supporting you. You own the vision and decisions, but you need help executing. This only works when you have the power to make final calls.

Peer collaboration.

You and your collaborators have equal standing but different expertise. Think designers and developers, or content strategists and product managers. You need each other’s skills to get the work done.

Consultant collaboration.

You’re brought in to provide an outside perspective. Your job is to spot what others can’t see (or say) and give them the tools to act on it. This type has built-in time limits and clear boundaries.

Cross-functional collaboration.

This involves people from different departments or disciplines working together. It’s often the messiest type because everyone has different goals, language, and ways of working.

Knowing what type of collaboration you’re in helps you set the right expectations for how decisions get made and who does what.

Approaches to CollaborationOnce you know what type of collaboration you’re in, you need an approach that fits the situation. Here are the most effective ways to collaborate as a sensemaker:

Start with questions, not solutions.

Ask people what drives their decisions. What are they measured on? What keeps them up at night? What would make their job easier? These questions help you understand their incentives, which is the foundation of good collaboration.

Map incentives before mapping architecture.

Before you propose any changes to structure or language, understand what each person involved is incentivized by. If their success depends on speed and yours depends on quality, you need to find the overlap before you start drawing diagrams.

Find the horse for your cart.

Don’t attach yourself to just anyone. Look for people whose momentum is already heading in a direction that helps you. If someone is incentivized by the exact thing your idea improves, that’s your collaboration partner.

Wait for the “until” moment.

Sometimes the best approach is patience. Organizations often can’t change until something forces them to. When that moment comes, be ready with your solution.

Speak their language.

If you’re talking to product managers, frame your ideas in terms of user metrics or revenue. If you’re talking to engineers, frame them in terms of technical efficiency or reducing bugs. In other words, match your message to what they care about.

If you’re new to intentional collaboration or feeling stuck, here’s how to start:

Make a list of what you want to change.

Write down the messes you see and why they matter. Be honest about which ones bug you personally versus which ones actually hurt the intention of the organization.

For each item on your list, ask: who has the power to make this change?

Not who agrees with you, who can actually approve it, fund it, or make it happen? Those are the people you need.

Research their incentives.

What are they measured on? What goals did they share in recent meetings or emails? What problems keep coming up for them? You can often find this out just by paying attention.

Look for overlap.

Where do your intentions and their incentives meet? That’s your opening for collaboration.

Start a conversation.

Don’t pitch your solution. Ask about their challenges. Listen to how they describe their goals. Look for the moment when you can say, “That connects to something I’ve been thinking about.”

Test the waters with something small.

Don’t propose a six-month project right away. Find a quick win that helps both of you and proves you can work well together.

Be ready to wait.

If the timing isn’t right, that’s okay. Keep building relationships so when the moment comes, you’re the first person they think of.

Get help from your manager.

If you’re hitting incentive walls, talk to your manager. They should be helping you navigate stakeholder dynamics and clear the path for your work.

These might sting a little, but they’re true:

Your good ideas don’t matter if no one with power cares. Being right isn’t enough. You need alignment with people who can actually act.

Most collaboration problems are actually incentive problems. If you’re constantly fighting with stakeholders, stop looking at their personality and start looking at what they’re measured on.

Managers who don’t help with incentive alignment aren’t managing. If your manager keeps telling you to “sell your ideas better” without helping you navigate stakeholder incentives, they’re not doing their job.

Sometimes the best collaboration is walking away. If you can’t find alignment and can’t change the incentives, it’s okay to stop trying. Save your energy for work that can actually move forward.

Being the expert doesn’t mean being in charge. You might know more about information architecture, ontologies, or knowledge management than anyone else, but if someone else owns the decision, you’re still in a support role. Act accordingly.

People quit over incentive misalignment more than anything else. If you’re surrounded by messes that no one will fix despite everyone agreeing they’re problems, that’s a sign of broken incentive architecture. That’s a management problem, not a you problem.

Collaboration without aligned incentives is just performance. You might have meetings and make decks and get nods of agreement, but nothing actually changes. Real collaboration requires everyone to need the same outcome.

Collaboration Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat if everyone agrees something is a mess but no one will fix it?

This is incentive misalignment. Everyone can see the problem, but fixing it doesn’t help any of them reach their goals. Your options: find someone whose incentives would be helped by fixing it, wait until external forces make fixing it necessary, or back-burner it.

How do I collaborate with someone who has more power than me?

Understand what drives their decisions. Frame your ideas in terms of what they care about. If you can’t find alignment, you might need their manager or peer to advocate with you. And remember: you can’t force someone with more power to change. You can only influence them if it helps them.

Should I collaborate on everything?

No. Some things you can do alone, and you should. Save collaboration for work that requires buy-in, resources, or power you don’t have. Not everything needs a working group.

How do I know if collaboration is working?

Things are moving forward. Decisions are being made. You’re not rehashing the same conversations every meeting. If you’re not seeing progress after a reasonable amount of time, something about the collaboration isn’t working.

What’s the difference between consensus and collaboration?

Consensus is everyone agreeing. Collaboration is working together toward a goal, even if you don’t all agree on every detail. You need aligned incentives for collaboration, not unanimous agreement.

Can I collaborate with people who have opposite incentives from me?

Not effectively. You might be able to work in parallel on different things, but true collaboration requires at least some shared goals. If your success hurts them or vice versa, you’re opponents, not collaborators.

How do I collaborate across teams with different languages and cultures?

Start by learning how each team talks about their work and what they care about. Translate your ideas into their terms. Find the person on each team who naturally bridges gaps: they’re worth their weight in gold.

—

Collaboration as a sensemaker isn’t about being more persuasive or making better presentations. It’s about understanding power, finding alignment, and knowing when to push, when to wait, and when to walk away.

We can only work smoothly when incentives are aligned. Everything else is just going through the motions.

Now go find your horse.

If you want to learn more about my approach to collaboration, consider attending my workshop on 11/21 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Working Together: Tools for Better Team Design — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in December – Change Management.

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Collaboration appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

October 17, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Return on Investment

The difference between good sensemaking and great sensemaking isn’t just about having the right answer. It’s about understanding what return you’re getting from the time, energy, and resources you put into making sense of complex problems.

This article covers:

What is Return on Investment in Sensemaking?Return on Investment (ROI) in sensemaking is the measurable value you get back from the time and resources you put into it.

Unlike traditional ROI calculations that focus purely on money, sensemaking ROI includes things like reduced confusion, faster decision-making, better team alignment, and fewer costly mistakes down the road.

Think of it this way: every hour you spend creating clear frameworks, consistent language, and logical structures either pays dividends later or it doesn’t. The question is whether you’re tracking which investments actually work. If you can’t figure out what was better when you were done, you might have made things worse.

Reasons to Focus on a Return on InvestmentYou’re drowning in requests for your opinion. When everyone sees you as the person with answers, demand can quickly outpace your ability to give thoughtful responses. Focusing on ROI helps you prioritize which sensemaking work will have the biggest impact.

Your past decisions are creating problems. Quick decisions made without considering the whole system can add up to a confusing mess. ROI thinking forces you to consider long-term consequences, not just immediate solutions.

You need to justify sensemaking work to others. Stakeholders often see sensemaking as “soft” work that’s hard to measure. Having clear ROI helps you make the case for investing in better structures and processes.

You want to prevent burnout. Constantly being the go-to person for answers is exhausting. Strategic thinking about ROI helps you build systems that reduce the need for your constant input.

Your organization is scaling. What works with 10 people breaks down with 100. ROI-focused sensemaking creates scalable foundations instead of person-dependent solutions.

Common Use Cases for Return on InvestmentBased on patterns I’ve seen across organizations, these are the areas where ROI questions come up most often. Each can create huge value when done well, or quietly drain resources when overdone, misplaced, or misaligned with goals.

Naming and Language ConsistencyShared language can clarify work, build trust, and prevent costly confusion, but teams can also lose months debating names that never reach users. The return depends on knowing when “good enough” is good enough.

Information OrganizationOrganizing information helps teams find, reuse, and act faster, until the structure itself becomes a maze. Over-modeling or premature taxonomy work can slow things down as much as chaos does.

Process DocumentationDocumenting reality saves time and reduces errors. Unless it turns into performative paperwork. The return shows up when documentation reflects living systems, not when it becomes a graveyard of outdated steps.

Framework CreationFrameworks can accelerate alignment and decision-making or paralyze teams if they’re treated as gospel. The best ones evolve with context; the worst ones outlive the problem they were meant to solve.

Types of Return on InvestmentAs you start to work through defining the expected return on your next investment, here are a few types of returns that I have seen repeatedly working on information architectures in all sorts of contexts.

Time SavingsWhen structures, language, and processes are clear, people spend less time searching, aligning, and repeating work. These savings can compound over time as the organization gains efficiency in how it learns and decides.

Cost ReductionCost-based returns emerge when better understanding prevents expensive mistakes. Clearer systems reduce duplication, unnecessary complexity, and the need for manual intervention. The fewer surprises and do-overs there are, the more sustainable the organization’s operations become.

Capability BuildingCapability-based returns come from improving the organization’s capacity to handle complexity. Each time a framework, model, or shared practice is created, the team becomes more adaptable and independent. These returns grow slowly but can provide lasting resilience.

Risk MitigationRisk-based returns show up as fewer crises and less uncertainty. When roles, processes, and information are well-structured, the organization becomes better at preventing problems and faster at recovering when they happen.

Profit GrowthProfit-based returns are the most visible to leadership and investors. They result when time, cost, quality, capability, and risk improvements combine to create more capacity for innovation, stronger customer relationships, and higher margins. Profit is often the byproduct of better sensemaking across the system, not just the goal itself.

Reputation and PerceptionReputation-based returns come from being understood and trusted. When an organization communicates clearly, acts consistently, and delivers on its promises, public perception improves. This strengthens relationships with customers, employees, and partners, creating a lasting form of goodwill that can’t easily be bought or rebuilt once lost.

Approaches to Return on InvestmentThere’s no single way to approach sensemaking ROI, but here are some things I would recommend:

The Pilot Project Approach Pick one small, messy area and invest in making sense of it. Measure before and after. Use those results to make the case for broader investment. This works well when you need to prove value before getting resources.

The Pain Point Method Start with the most expensive confusion in your organization. What’s causing the most rework, delays, or frustration? Target your sensemaking efforts there first. The ROI is often immediately visible.

The Systems Thinking Strategy Map out how your current sensemaking decisions connect to each other. Look for places where better structure in one area could improve multiple other areas. This strategy works well when you are able to have a high level view of a broad structural issue.

The User Journey Focus Follow a specific path from start to finish and note every point where confusion slows things down. Then develop solutions that smooth the most friction-heavy parts of the journey.

Tips for Getting Started with Return on InvestmentStart with “How will we know if this works?”

Before diving into any sensemaking project, get specific about what success looks like. Will it save time? Reduce errors? Improve satisfaction? Make sure you can actually measure whatever you choose.

Track your current state

You can’t measure improvement without knowing where you started. Document how long things currently take, what mistakes happen regularly, and where people get confused most often.

Pick battles you can win

Your first ROI-focused project should be something where you can show clear results quickly. Success builds credibility for bigger investments later.

Get friendly with data people

The people who manage your organization’s data know where the measurement gold is buried. They can also tell you what’s actually possible to track versus what sounds good in theory.

Document your process, not just your outcomes

Future you (and your teammates) will want to know how you got your results, not just what they were. This makes your sensemaking ROI repeatable and teachable.

Expect resistance to structure

People often resist new frameworks or processes, even when they’ll ultimately help. Plan for this resistance and have a strategy for getting buy-in.

Ask “What Keeps You Up at Night About This?”

This question disarms stakeholders enough to tell you the truth about what’s really at stake in your work. In my experience time and time again, this has been the question that unlocks the problem set.

Most sensemaking work has terrible ROI because it’s reactive instead of strategic. Answering individual questions as they come up feels productive, but building systems that prevent those questions has much better returns.

The best sensemaking ROI comes from reducing your own workload. If your sensemaking work doesn’t eventually make you less necessary for day-to-day decisions, you’re probably doing it wrong.

Perfect frameworks have worse ROI than good-enough frameworks that people actually use. Don’t let the pursuit of the ideal prevent you from implementing something that works.

Teaching others to think like sensemakers has better long-term ROI than doing all the sensemaking yourself. Your goal should be to work yourself out of being the bottleneck.

The highest ROI sensemaking work often looks boring. Consistent naming conventions and clear documentation aren’t sexy, but they pay dividends for years.

Return on Investment Frequently Asked QuestionsQ: How do I measure ROI when the benefits are mostly qualitative?

A: Look for proxy metrics. If something “improves clarity,” that might show up as reduced email back-and-forth, fewer revision cycles, or higher confidence scores in surveys. The key is finding measurable outcomes that connect to your qualitative goals.

Q: What if I can’t get data on current performance?

A: Start tracking now, even if it’s imperfect. You can estimate baselines through surveys, time-tracking exercises, or small observational studies. Having rough numbers is better than having no numbers.

Q: How long should I wait to measure ROI?

A: It depends on what you’re measuring. Time savings might be visible within weeks, while culture changes could take months. Set both short-term and long-term measurement points.

Q: What if my sensemaking investment doesn’t show positive ROI?

A: Learn from it. Understanding what doesn’t work is valuable data for future investments. Also consider whether you’re measuring the right things or if the benefits are showing up somewhere unexpected.

Q: Should I focus on easy wins or big transformations?

A: Start with easy wins to build credibility and learn your measurement process. Once you’ve proven your approach, you can tackle bigger challenges with more confidence and support.

Q: How do I balance ROI thinking with intuitive sensemaking?

A: Good sensemaking combines both. Use your intuition to identify opportunities and design solutions, then use ROI thinking to prioritize investments and measure success. They’re complementary, not competing approaches.

–

Understanding the return on investment in your sensemaking work isn’t just about justifying your time—it’s about making sure your efforts actually create the clarity and understanding your organization needs. By thinking strategically about which confusion to tackle first and how to measure your impact, you can transform from someone who gives good answers to someone who builds systems that help everyone find their own answers.

The goal isn’t to turn sensemaking into a purely numbers-driven practice, but to make sure your ability to create clarity is focused where it can do the most good.

If you want to learn more about my approach to strategic sensemaking, consider attending my workshop on 10/25/25 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. A Return on Investment Matters: Building a Business Case for IA – this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in November – Collaboration in IA

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Return on Investment appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

September 12, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Arguing

You know that moment when you have a brilliant idea for fixing something that’s clearly broken, but then you realize the hard part isn’t figuring out the solution—it’s getting everyone else to see it too?

Welcome to the real work of sensemaking. The messy, human part where good ideas go to die unless you know how to argue for them properly.

Most people think arguing is about winning or being stubborn. But for sensemakers, arguing is how we turn individual insights into shared understanding. It’s how we test ideas against reality before they get expensive.

This article covers:

Why is there Arguing in Sensemaking?When you’re trying to make sense of complex problems, you need ways to pressure test your thinking. Not because you enjoy conflict, but because untested ideas become expensive mistakes.

Think about it: every structural change, every new process, every “better way of doing things” has to survive contact with real people, real constraints, and real trade-offs. Arguing early helps you find the weak spots before they find you.

Good arguing helps you:

Surface hidden assumptions before they derail your proposalBuild empathy for the people who have to live with your solutionGet clearer on scope, risks, and what success actually looks likeTurn resistance into collaboration by addressing concerns head-onReasons to ArgueWhen you argue properly, you’re essentially stress-testing your thinking before it hits reality. You’re creating what I call “comparability” or a level(er) playing field where you can honestly evaluate different approaches against each other. This process forces hidden assumptions into the open and makes trade-offs visible before they bite you.

But arguing isn’t just about finding flaws. It’s about building confidence that your proposal can survive contact with the real world. If your idea crumbles under friendly questioning, imagine what happens when it meets actual users, tight deadlines, and budget constraints.

Most importantly, arguing keeps you from falling in love with your first idea. That initial solution that feels so obvious? It’s usually not your best work. The discipline of considering alternatives—even if you end up sticking with your original approach—makes your final proposal stronger and your reasoning clearer.

Common Use Cases for Arguing in SensemakingStructural changes: When proposing new ways to organize information, processes, or teams. Challenge your classification rules, question your content strategy, and stress-test your curation plans.

Resource requests: Before asking for budget, time, or people, argue through the real costs and benefits. Include the hidden costs like training, migration, and ongoing maintenance.

Priority decisions: When everything feels urgent, arguing helps you surface the real criteria for what matters most. Question timelines, challenge scope, and get clear on trade-offs.

Process improvements: Before proposing a new workflow, argue through who gets impacted and how. Consider the people who have to live with your process every day.

System design: Challenge your mental models. Question whether your structure will make sense to users. Test your assumptions about how people will actually behave.

Types of ArgumentsNot all arguments are created equal. Here are five forms that reliably strengthen your work.

Evidence-based arguments: Ground your thinking in real data about real users.

Example: “Our content audit shows 40% of pages haven’t been updated in two years” is stronger than “I think our content is stale.”

Structural arguments: These examine how well a proposed structure serves its intended purpose. Question classification rules, content lifecycle, and curation requirements.

Example: “Putting product specs in the same category as marketing pages makes the structure harder to maintain long-term” is stronger than “I don’t like where those pages are.”

Trade-off arguments: These make the costs visible.

Example: “This approach requires hiring two people and six months of data cleaning” is stronger than “this might be expensive.”

Constraint arguments: These test proposals against real limits.

Example: “What if we only had half the timeline?” or “What if our main content creator leaves?” is better than “let’s cross that bridge when we get to it”

User mental model arguments: These focus on how people will actually interpret and use your structure.

Example: “Users think of pricing as part of the buying decision, not a buried FAQ item.” is stronger than “Users can’t find pricing”

Approaches to ArgumentsCreate an Alternative Structure Never argue for just one approach. Create at least two different structures that could meet your goals. This forces you to think harder about why one is better.

Run a Structural Argument Check Evaluate proposals against intention, information, content, facets, classification, curation, and trade-offs. If any component feels weak, dig deeper. I wrote a lengthy article on Structural Arguments that should serve as a helpful guide if you take this approach on.

Take on the Implementation Reality Test Ask “What would it actually take to build and maintain this?” Include all the unglamorous stuff like data migration, training, and ongoing updates.

Dig into the User Interpretation Challenge Test whether your structure makes sense to the people who have to use it. Don’t just ask if they like it—watch how they actually interpret it.

Go into Failure Mode Ask “What could break this?” Think about edge cases, unusual content, and situations where your rules don’t apply clearly.

Tips for Getting Started with ArguingDocument your thinking Don’t just have opinions—show your work. Write down your assumptions, your reasoning, and your evidence.

Start with intention Always connect your proposal back to the larger “why.” If you can’t explain how your structure serves the real goals, it’s not ready.

Get specific about content Vague ideas fall apart when they meet real content. Know what you’re organizing, who creates it, and how it changes over time.

Name the trade-offs Every good proposal involves giving up something to get something else. If you can’t find any downsides, you haven’t thought hard enough.

Test with real scenarios Don’t just theorize—walk through actual use cases. What happens when someone uploads something that doesn’t fit your categories?

Plan for maintenance How will your structure stay healthy over time? Who will keep it updated? What happens when priorities shift?

Arguing Hot TakesHot take #1: If you can’t argue against your own proposal, it’s not ready The best way to strengthen an idea is to attack it yourself first. Find the weak spots before someone else does.

Hot take #2: Most structures fail because of content, not concepts Beautiful organizational schemes collapse when they meet real content with all its messy inconsistencies and edge cases.

Hot take #3: Your users don’t care about your mental model They have their own way of thinking about things. Your structure needs to match their expectations, not your internal logic.

Hot take #4: Implementation is where good ideas go to die The best structural proposal is worthless if you can’t execute it with real people, real budgets, and real timelines.

Hot take #5: Second solutions are usually better than first solutions Your initial idea might be good, but the alternative you create to argue against it is often simpler and stronger.

Frequently Asked QuestionsQ: How do I argue for changes when stakeholders seem happy with the status quo? A: Make the hidden costs of the current approach visible. Show what’s breaking, what’s inefficient, and what opportunities are being missed.

Q: What if my proposal requires resources we don’t have? A: That’s valuable information. Either scope down your proposal or make the case for why the resources are worth it. Don’t pretend expensive things are cheap.

Q: How detailed should my arguments be? A: Detailed enough to be credible, simple enough to be understood. If you’re losing people in the details, you need clearer main points.

Q: What if stakeholders focus on parts of my proposal I think are minor? A: Those parts probably aren’t as minor as you think. Pay attention to what people care about—it tells you something important about their mental models.

Q: How do I argue without seeming negative or difficult? A: I hear this a lot when people talk about argument. In trying not to seem “argumentative,” we forget that change only happens if we argue for it. The key is framing position arguments as ways to make a proposal stronger, not as ways to tear it down. Saying “Let’s pressure test this so it succeeds” lands far better than “Here’s what’s wrong with this.”

Q: Should I present multiple options to stakeholders? A: Sometimes. It can lead to better discussions, but it can also create decision paralysis. Use your judgment about whether comparison helps or hurts.

Remember: the goal isn’t to win arguments. The goal is to build better solutions. When you argue well, everyone wins because the ideas get stronger and the implementation gets smoother.

The real work of sensemaking isn’t coming up with solutions. It’s doing the hard thinking to turn those solutions into reality.

If you want to learn more about my approach to structural argumentation, consider attending my workshop on September 19th from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. How to Argue (for IA) Better — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in October — Proving a Return on Investment.

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Arguing appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

August 8, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Taxonomies

Let’s cut to the chase: taxonomy is one of those words that makes people’s eyes glaze over. But here’s the thing, you’re already doing it whether you know it or not.

Every time you organize your photos into folders, sort your emails, or decide which drawer the kitchen scissors belong in, you’re creating a taxonomy. You’re making sense of the world by putting like things together and giving them names that help you find them later.

The difference between what you do at home and what we do professionally is scale, stakes, and the number of people who need to understand your logic.

What is Taxonomy?Taxonomy is the practice of classifying things into categories and giving those categories names that make sense to the people who will use them.

That’s it. No fancy jargon needed.

It’s about creating buckets for your stuff, whether that stuff is products, content, data, or any other kind of information, and making sure those buckets have clear, useful labels.

The word comes from biology, where scientists organize living things into kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. But you don’t need to be a scientist to benefit from taxonomic thinking. You just need to have stuff that needs organizing.

Reasons for TaxonomyWhy bother with taxonomy at all? Because without it, you’re drowning in chaos.

Findability: When things are properly categorized and labeled, people can find what they’re looking for. When they’re not, even the best search engine can’t help you.

Consistency: Taxonomy creates shared language within your organization. Instead of everyone calling the same thing by different names, you establish what goes where and what to call it.

Scalability: As your collection of stuff grows, taxonomy keeps it manageable. Without it, growth becomes clutter, and clutter becomes paralysis.

Decision-making: Clear categories make it easier to spot patterns, identify gaps, and make informed choices about what to keep, change, or throw away.

User experience: When people can predict where to find things, they feel more confident and capable. When they can’t, they feel frustrated and lost.

Common Use Cases for TaxonomyTaxonomy shows up everywhere, often disguised as something else:

Website navigation: Those menu items and page categories? That’s taxonomy at work, helping users understand how information is organized.

Product catalogs: Whether you’re selling shoes or software, customers need to be able to browse by category, filter by attributes, and understand what makes one product different from another.

Content management: Blog posts, articles, documents, and media files all need homes. Taxonomy provides the filing system that keeps content organized and discoverable.

Data organization: Customer records, financial information, research findings. All of this needs to be categorized in ways that make analysis and reporting possible.

Knowledge management: Company policies, procedures, best practices, and institutional knowledge need structure so people can find and use what they need.

Compliance and governance: Legal, regulatory, and internal requirements often demand specific ways of categorizing and labeling information.

Types of TaxonomiesNot all taxonomies are created equal. Here are the main types you’ll encounter:

Hierarchical taxonomies work like family trees, with broad categories at the top and increasingly specific subcategories below. Think of how a library organizes books: literature → fiction → mystery → detective novels.

Faceted taxonomies let you slice and dice the same items in multiple ways. An online store might let you browse clothing by size, color, style, and price range all at once.

Flat taxonomies keep everything at the same level, like tags on a blog post. There’s no hierarchy, just a bunch of labels that can be applied as needed.

Network or polyhierarchical taxonomies allow items to belong to multiple categories and show relationships between different branches. They’re messier but often more realistic.

Sequences are conditions-based arrangements of content that progress over time.

Folksonomies are when users create their own tags and categories organically. It’s democratic but can get chaotic quickly.

Approaches to TaxonomyThere are two main ways to build a taxonomy: top-down and bottom-up.

Top-down means starting with the big picture and working your way down to the details. You decide on major categories first, then figure out subcategories, then specific items. This approach works well when you have a clear vision of how things should be organized and enough authority to make it stick.

Bottom-up means starting with the individual items and looking for patterns that suggest natural groupings. You sort through everything you have, notice what goes together, and build categories around those relationships. This approach works better when you’re dealing with existing content or when you need buy-in from people who are close to the material.

Most successful taxonomy projects use both approaches, moving back and forth between big-picture thinking and detailed sorting until everything clicks into place.

Tips for Getting Started with TaxonomyStart with your users, not your org chart: The best taxonomies reflect how people actually think about and use information, not how your company happens to be structured.

Use words people recognize: If your audience calls them “pants,” don’t label the category “lower body garments.” Meet people where they are, not where you think they should be.

Test early and often: Show your taxonomy to real users and watch how they interact with it. Where do they get confused? What do they expect to find that isn’t there?

Keep it simple: Resist the urge to create categories for every possible variation. Sometimes “miscellaneous” is exactly what you need.

Plan for growth: Your taxonomy should be able to handle new types of content without breaking. Build in flexibility from the start.

Document your decisions: Write down why you made certain choices. Six months from now, you’ll be grateful for the reminder.

Start small: Don’t try to organize everything at once. Pick one area, get it right, then expand from there.

Taxonomy Hot TakesHere are some opinions that might ruffle feathers:

Perfect taxonomies don’t exist: There’s no such thing as a taxonomy that works perfectly for everyone. Stop trying to create one and focus on making something that works well enough for your specific context.

Users will break your taxonomy: Plan for it. People will put things in the wrong categories, use labels incorrectly, and generally ignore your beautiful logic. Design for human behavior, not human ideals.

Taxonomy is never finished: It’s a living system that needs ongoing attention. If you’re not regularly reviewing and updating your taxonomy, it’s already out of date.

Consensus is overrated: Sometimes you need to make a decision, agree to measure the results and move on. Waiting for everyone to agree on the perfect category name is a recipe for paralysis.

Most taxonomy problems are actually communication problems: If people can’t understand or use your taxonomy, the issue usually isn’t with the categories themselves—it’s with how you’ve explained or framed them.

Taxonomy Frequently Asked QuestionsQ: How many categories should I have? A: As few as possible while still being useful. Research suggests people can handle about ~7 top-level categories before they start getting overwhelmed.

Q: Should I use single words or phrases for category names? A: Whatever makes the most sense to your users. Single words are cleaner but phrases can be clearer. Test both and see what works.

Q: What if something could belong in multiple categories? A: That’s what cross-references and polyhierarchy is for. Don’t force things into artificial boxes just to maintain hierarchy. But also remember if everything is in every category, “category” loses it’s meaning.

Q: How do I handle overlap between categories? A: Some overlap is inevitable and even helpful. The goal isn’t perfect boundaries—it’s useful boundaries. The size and nature of the overlap matter a lot when determining how to handle it. This is something live card sorting with users can really help to smooth out.

Q: Should I involve users in creating the taxonomy? A: Absolutely, but don’t expect them to design it for you. Get their input on how they think about the content, then translate that into a working system.

Q: How often should I update my taxonomy? A: Regularly but not constantly. Set up a review schedule—maybe quarterly or twice a year—and stick to it.

Q: What’s the biggest mistake people make with taxonomy? A: Making it too complicated. The best taxonomies feel obvious once you see them.

—

If you want to learn more about my approach to Taxonomy, consider attending my workshop on 8/15/25 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Building Better Buckets: Hands-on Taxonomy Design — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in September is Argumentation

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Taxonomies appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

July 18, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Metadata

Metadata is everywhere. It’s the invisible backbone that makes our digital world work. Yet most people treat it like an afterthought—slapping on tags and labels without much care. That’s a mistake. Good metadata can transform chaos into clarity. Bad metadata makes everything harder to find, use, and understand.

This article covers what metadata actually is, why you should care about it, and how to approach it thoughtfully. Whether you’re organizing a personal photo collection or building enterprise systems, the principles remain the same.

What is Metadata?Metadata is data about content. It’s data that describes, explains, or gives context to content.

Think of a library book. The book itself is the content. The catalog card with the title, author, publication date, and subject tags? That’s metadata. It helps you find the book, understand what it’s about, and decide if it’s what you need.

In digital systems, metadata works the same way. Every file on your computer has metadata—creation date, file size, who made it. Every photo has metadata about when and where it was taken, what camera settings were used. Every webpage has metadata that tells search engines what the page is about.

Metadata makes things findable, usable, and meaningful.

Reasons to Think About MetadataMost people ignore metadata until they desperately need to find something. By then, it’s too late. Here’s why metadata deserves your attention upfront:

Finding stuff becomes possible. Without good metadata, finding information is like looking for a book in a library where all the books are randomly scattered on shelves. Sure, you might stumble across what you need eventually. But probably not.

Context stays attached. Information without context is just noise. Metadata preserves the who, what, when, where, and why that makes data meaningful. A spreadsheet called “Q3_numbers.xlsx” tells you nothing. But when the metadata shows it was created by Ahmed in Finance on October 15th for the board presentation, suddenly it has meaning.

Systems can connect and share. Well-structured metadata lets different systems talk to each other. Your customer database can connect to your email system because they both understand what a “customer ID” means. Without shared metadata standards, every system becomes an island.

Change becomes manageable. Organizations evolve. People leave. Systems change. But if your metadata is solid, institutional knowledge doesn’t walk out the door. New people can understand what exists and why it matters.

Common Use Cases for MetadataMetadata shows up everywhere, but some patterns repeat across industries and contexts:

Content management uses metadata to organize articles, images, videos, and documents. Publishers tag articles by topic, author, and publication date. Photo agencies tag images by subject, location, and rights information. Without this metadata, content libraries become unusable quickly.

Data governance relies on metadata to track where data comes from, how it’s changed, and who can access it. In regulated industries, you need to prove your data is accurate and secure. Metadata provides that proof.

Search and discovery systems use metadata to understand what users are looking for. When you search for “red shoes” on an e-commerce site, you’re not searching the product images. You’re searching metadata tags like color, category, and description.

Asset management tracks physical and digital resources through their lifecycle. A manufacturing company needs to know which equipment needs maintenance, when it was last serviced, and who’s responsible for it. That’s all metadata.

Compliance and legal requirements often mandate specific metadata. Healthcare records need patient identifiers and access logs. Financial records need transaction details and approval chains. Legal documents need version history and confidentiality markings.

Types of MetadataNot all metadata serves the same purpose. Understanding the different types helps you choose the right approach:

Descriptive metadata tells you what something is about. Title, author, subject, keywords, abstract. This is what most people think of when they hear “metadata.” It’s designed for humans who need to understand and categorize information.

Structural metadata explains how something is organized. Chapter headings in a book. Folder hierarchies on a computer. Database relationships. This metadata shows how pieces fit together into a larger whole.

Administrative metadata tracks the business side of information. Who owns it, who can access it, when it expires, how much it costs. This metadata supports governance and compliance requirements.

Technical metadata describes the nuts and bolts. File formats, compression settings, database schemas, API specifications. This metadata helps systems process and exchange information correctly.

Preservation metadata ensures information survives over time. Migration history, format dependencies, checksums for integrity verification. This metadata fights against digital decay and obsolescence.

Approaches to MetadataHow you create and manage metadata depends on your situation, but three basic approaches dominate:

Manual metadata creation means humans write tags, descriptions, and classifications by hand. This produces the highest quality metadata because humans understand context and nuance. But it’s slow, expensive, and doesn’t scale well. Use manual approaches for high-value content where accuracy matters more than speed.

Automated metadata extraction uses software to pull metadata from content itself. File properties, GPS coordinates from photos, text analysis for keywords. This scales beautifully and costs almost nothing. But automated systems miss context and make weird mistakes. Use automation for large volumes of routine content.

Hybrid approaches combine human intelligence with machine efficiency. Automated systems generate draft metadata that humans review and refine. Or humans create metadata templates that machines populate with specific values. Most successful metadata programs use hybrid approaches.

The key is matching your approach to your constraints. If you have unlimited time and budget, go manual. If you have unlimited content and tight budgets, you might start with automated and see where it gets you. Most people fall somewhere in between.

Tips for Getting Started with MetadataStarting a metadata program can feel overwhelming. Here’s how to begin without drowning:

Start small and specific. Don’t try to take care of everything at once. Pick one collection, one system, or one workflow. Figure out what works there before expanding.

Focus on what people actually need. Metadata is only valuable if someone uses it. Talk to the people who will search, sort, and filter your content. What questions do they ask? What problems do they face? Design your metadata around real needs, not theoretical completeness.

Steal shamelessly from standards. You don’t need to invent metadata from scratch. Standards like Dublin Core, EXIF, and Schema.org solve common problems. Use them as starting points, then customize for your specific needs.

Make it as easy as possible. The easier metadata creation is, the more likely people will do it consistently. Use dropdown menus instead of free text. Provide templates and examples. Automate whatever you can.

Plan for change. Your metadata needs will evolve. Build flexibility into your system from the start. Use extensible schemas. Document your decisions. Make it easy to add new fields or change existing ones.

Measure and iterate. Track how people actually use your metadata. What searches succeed or fail? Which tags get used and which get ignored? Use this data to improve your approach over time.

Metadata Hot TakesAfter years of working with metadata across different industries, I’ve developed some strong opinions:

Perfect metadata is the enemy of good metadata. Don’t let the pursuit of completeness prevent you from starting. Partial metadata is infinitely more valuable than no metadata.

Folksonomies beat taxonomies for many use cases. Sometimes it makes the most sense to let people tag things with their own words rather than forcing them into rigid categories. You can always clean up and standardize later. I find folksonomies to be playing double roles as metadata extraction and user research.

Metadata degrades over time. Information changes, but metadata often doesn’t. Build maintenance and review processes into your workflow, or accept that your metadata will become less accurate over time.

Context matters more than completeness. Better to have three relevant, accurate metadata fields than thirty fields that nobody understands or maintains.

The best metadata schema is the one people actually use. Academic perfection means nothing if your real users ignore it. Design for human behavior, not theoretical ideals.

Metadata Frequently Asked QuestionsHow much metadata is enough? Enough to solve the problems you’re trying to solve, but not so much that creation and maintenance become burdensome. Start minimal and add fields as you discover specific needs.

Should we use controlled vocabularies or free text? Both have advantages. Controlled vocabularies ensure consistency but limit expressiveness. Free text captures nuance but creates inconsistency. Consider hybrid approaches where you provide suggested terms but allow custom entries.

How do we get people to actually create metadata? Make it easy, make it valuable, and make it part of the workflow. If metadata creation feels like extra work, people won’t do it consistently. Integrate it into existing processes and show clear benefits.

What about privacy and security? Metadata can reveal sensitive information even when the underlying data is protected. Location metadata in photos, access patterns in logs, relationship information in tags. Consider what your metadata exposes and protect it accordingly.

How do we handle metadata when systems change? Plan for migration from the beginning. Use standard formats where possible. Document your metadata schema clearly. Export metadata regularly as backup. Consider metadata portability when choosing systems.

Should we outsource metadata creation? Outsourcing works well for routine, high-volume metadata like basic cataloging or keyword tagging. Keep specialized, contextual metadata creation in-house where domain expertise matters.

—

If you want to learn more about my approach to metadata, consider attending my workshop on July 25 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Tag It Right: Building Better Data Descriptions — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in August – Thoughtful Taxonomies!

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Metadata appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

June 13, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Controlled Vocabularies

Have you ever been in a meeting where half the room calls something a “segment” while the other half calls it an “clip”? Or maybe you’ve built a navigation menu where the same content could logically fit under multiple labels, depending on who is doing the sorting? If you’re nodding your head right now, you’ve felt the pain that comes from messy language. The good news? There’s a tool for that.

Today we’re diving into controlled vocabularies – one of the most powerful yet often overlooked tools in our sensemaking toolkit. Let’s cut through the confusion together.

This article covers:

What is a Controlled Vocabulary in Sensemaking?A controlled vocabulary is simply an agreed-upon set of terms that a group uses consistently. It’s a list of words that everyone promises to use the same way, to mean the same things. No fancy jargon needed.

Think of it as a language contract that says, “When we say X, we all agree it means Y – not Z.”

At its core, a controlled vocabulary helps groups of people speak the same language, even when they come from different backgrounds or departments. It’s the difference between talking past each other and truly connecting.

Reasons to Use Controlled VocabulariesWhy bother with all this word-wrangling? Here’s the straight talk:

Clearer communication. When everyone uses the same words to mean the same things, we waste less time explaining ourselves.Better findability. Content, data, and information become much easier to find when everything is labeled consistently.Reduced confusion. Those painful “wait, what do you mean by that?” moments happen less often.Simpler onboarding. New team members can get up to speed faster when there’s a shared language in place.More accurate data. Reports, analytics, and insights improve when we’re all tracking the same things under the same names.Less rework. How many hours have you lost to misunderstandings that could have been prevented with clearer terms?Common Use Cases for Controlled VocabulariesYou might be surprised at how often controlled vocabularies show up in your work:

Navigation systems: Ensuring menu items and labels make consistent sense across an entire websiteContent tagging: Helping writers and editors apply consistent categories and tagsData entry: Making sure everyone fills out forms with comparable informationSearch systems: Improving the accuracy of search results by connecting related termsProduct catalogs: Organizing products in ways that customers can actually find themKnowledge bases: Making information retrievable across teams and departmentsProject management: Ensuring everyone understands workflow status labels the same wayIndustry standards: Creating shared understanding across organizations (think medical terminology or legal documents)Types of Controlled VocabulariesNot all controlled vocabularies work the same way. Here are the main types you’ll encounter:

Simple Lists are exactly what they sound like – straightforward collections of preferred terms. These work well for smaller sets of words that don’t have complex relationships (like acceptable status values: “draft,” “in review,” “approved”).

Synonym Rings connect different words that mean basically the same thing. They help people find what they need regardless of the specific term they use (like connecting “car,” “automobile,” and “vehicle”).

Taxonomies organize terms into parent-child relationships, creating hierarchies that show how concepts relate. They’re perfect for organizing content into broader and narrower topics (like Animals → Mammals → Cats → Domestic Cats).

Thesauri are like taxonomies but include not just hierarchical relationships but also associative ones – terms that relate to each other but aren’t directly above or below each other. They often include scope notes that explain exactly how to use each term.

Ontologies are the most complex type. They define concepts, their properties, and the relationships between them with extreme precision. They’re often used in artificial intelligence systems to represent knowledge.

Approaches to Creating Controlled VocabulariesThere are a few ways to build a controlled vocabulary, and the right approach depends on your situation:

Top-down approach: Start with high-level categories determined by experts, then work down to more specific terms. This works well when you have clear domain knowledge and defined requirements.

Bottom-up approach: Begin by gathering the actual terms people are already using, then organize them into patterns. This is great when you’re working with existing content or want to align with how people naturally talk.

Hybrid approach: Most successful vocabularies combine both methods – using expert guidance while also respecting how users actually think and talk about things.

Collaborative approach: Involving stakeholders from across your organization often leads to vocabularies that are more likely to be adopted. When people help build it, they’re more likely to use it.

Borrowed approach: Sometimes the smartest move is to adopt an existing industry standard vocabulary rather than creating your own. Why reinvent the wheel?

Tips to Getting Started with Controlled VocabulariesReady to bring some order to the chaos? Here’s how to begin:

Start small. Pick one area where terminology confusion causes real problems, rather than tackling everything at once.Listen first. Before prescribing terms, take time to understand what words people are already using and why.Focus on painful points. Target the terms that cause the most misunderstandings or wasted time when used inconsistently.Document everything. A controlled vocabulary only works when it’s written down somewhere accessible – not just in your head.Include definitions. Don’t just list terms; explain exactly what each one means and how it should be used.Plan for governance. Decide upfront who can add, change, or remove terms, and how that process will work.Build in feedback loops. Language evolves, so create ways for people to suggest improvements or request new terms.Think about format. Will a simple spreadsheet do the job, or do you need specialized tools to manage your vocabulary?Consider maintenance from day one. Controlled vocabularies need upkeep. Who will own that responsibility long-term?Communicate the value. Help others understand how consistent language will make their work easier, not just add another rule to follow.Controlled Vocabulary Hot TakesLet me share a few things I’ve learned the hard way:

Perfect is the enemy of useful. An imperfect vocabulary that people actually use beats a perfect one that sits in a document nobody opens.Force rarely works. You can’t usually mandate language by decree. Focus on making your vocabulary so helpful that people want to use it.The goal is clarity, not control. Despite the name, successful controlled vocabularies are more about creating shared understanding than policing language.Natural language will always be messy. No controlled vocabulary will eliminate all ambiguity – and that’s okay. We’re aiming for “better,” not “perfect.”Technology alone won’t save you. The fanciest taxonomy tool in the world won’t help if you haven’t done the human work of reaching agreement first.Controlled Vocabulary Frequently Asked QuestionsHow big should my controlled vocabulary be? Only as big as necessary to solve your specific problems. Start small and grow as needed.

What’s the difference between a taxonomy and a controlled vocabulary? A taxonomy is a type of controlled vocabulary – specifically one that organizes terms into hierarchical relationships.

Who should be responsible for maintaining our controlled vocabulary? Ideally, someone who understands both the subject matter and how language works. Often this falls to information architects, content strategists, or librarians.

How do I get people to actually use our agreed-upon terms? Make it easy (build the vocabulary into tools where possible), make it visible (keep it accessible), and make it valuable (show how it solves real problems).

How often should we update our controlled vocabulary? Plan for regular reviews – perhaps quarterly for active areas. But also create channels for immediate feedback when urgent issues arise.

What tools should we use to manage our controlled vocabulary? It depends on size and complexity. A spreadsheet or shared document works for smaller vocabularies, while dedicated taxonomy management software might be needed for larger efforts.

Language is how we make sense of the world together. When we’re careless with our words, we create unnecessary confusion. Controlled vocabularies give us a practical way to build shared understanding – not by restricting creativity, but by creating a foundation of clarity that actually enables more meaningful work.

Whether you’re wrestling with inconsistent product categories, tangled metadata, or team members who seem to be speaking different languages, a thoughtful approach to vocabulary can transform chaos into clarity.

If you want to learn more about my approach to controlled vocabularies, consider attending my workshop on June 20th from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Word Choice Wars: Building Controlled Vocabularies That Work — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in July – Designing with Metadata.

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Controlled Vocabularies appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

May 9, 2025

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Diagramming & Modeling

When was the last time you felt stuck? Maybe it was a complex project with too many moving parts. Perhaps it was a difficult conversation where words alone weren’t getting your point across. Or maybe it was simply trying to understand something that felt just beyond your grasp.

Whatever it was, I bet a diagram would have helped.

This article covers:

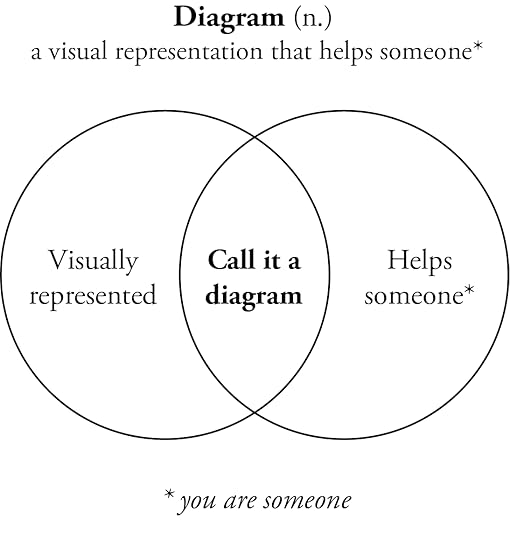

What is Diagramming? What is Modeling?Let’s start with a simple definition:

A diagram is a visual representation that helps someone.

That’s it. If it’s visually represented and it helps someone (even if that someone is just you), congratulations—you’ve made a diagram.

Modeling is creating a representation of something to help us understand it better.

Models don’t have to be visualized to be represented, but when we visualize models, we’re diagramming. For example, writing out the definition of diagram like the above might be the right representation of the model I am trying to teach, but a diagram might help draw the attention of the audience to the two pieces coming together.

The distinction between the two is subtle but important:

Diagramming is about creating a visual artifactModeling is about the thinking process behind itReasons to DiagramWhen we face volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, diagrams offer us:

Stability in times of volatilityTransparency when facing uncertaintyUnderstanding of complexityClarity through ambiguityKindness to ourselves and othersThat last one might surprise you, but diagrams truly are an act of kindness. They reduce cognitive load and create shared understanding. They give us a place to put our thinking so our brains can rest.

Common Use Cases for DiagrammingPeople diagram for countless reasons, but some common scenarios include:

Explaining complex systems to people who need to understand themFacilitating decision-making by visualizing options and relationshipsPlanning projects by mapping tasks, timelines, and dependenciesAnalyzing problems by breaking them down into manageable piecesCommunicating concepts that are difficult to express in words aloneOrganizing information to reveal patterns and insightsCreating a shared understanding among team members or stakeholdersTypes of ModelsBelow are some of the types of models you are likely to run into in the wild world of sensemaking.

Structural modelA structural model defines the static relationships between entities or components within a system. It answers “What exists and how is it connected?”

These models typically include classes, objects, components, or data structures and their relationships.

Example: Airbnb’s database schema

Airbnb uses a structural model to define how entities like Users, Listings, and Bookings relate.

Process modelA process model illustrates the sequence of activities, decisions, and flows in a system or workflow. It answers “What happens, in what order, and under what conditions?”

Common formats include flowcharts, BPMN diagrams, and swimlane diagrams.

Example: Amazon’s order fulfillment workflow

Amazon uses a Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) process model to map how an order moves from purchase to delivery:

Behavioral modelA behavioral model represents how a system reacts to internal or external inputs over time. It answers “How does the system behave or respond?”

Often includes state machines, interaction diagrams, or logic models.

Example: Thermostat control logic in Nest

The Nest Thermostat uses a behavioral model to decide when to heat or cool based on sensor input.

Conceptual modelA conceptual model represents how users or stakeholders understand a system or domain. It answers “How do people think this works?”

These are often simplified, abstract representations used to align mental models.

Example: Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines

Apple’s design team maintains a conceptual model of how users understand navigation across iOS apps.

Mathematical modelA mathematical model uses mathematical expressions, algorithms, or statistical methods to simulate real-world phenomena. It answers “What can we calculate, predict, or optimize?”

Includes equations, formulas, and algorithmic logic.

Example: Netflix’s recommendation algorithm

Netflix uses a mathematical model called collaborative filtering.

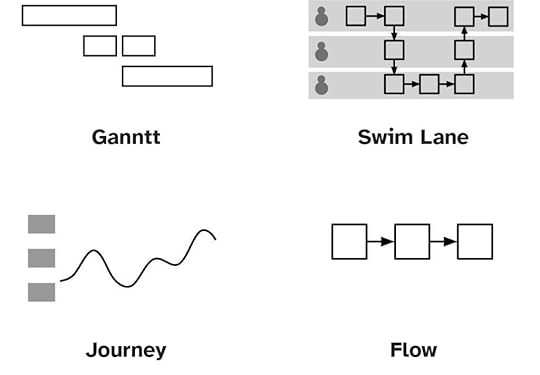

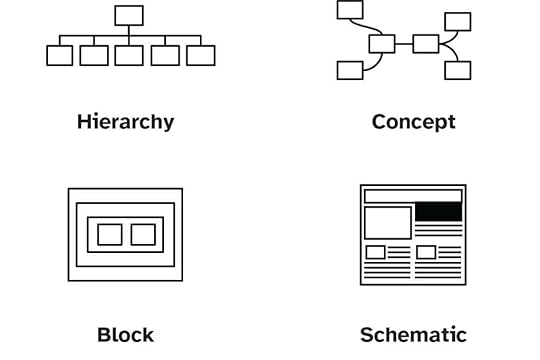

Types of DiagramsThere are countless types of diagrams out there. A common way to differentiate them is qualitative vs. quantitative. I like to think about types differently. Centering is concentration on a specific point. In my book, Stuck? Diagrams Help. I propose three main centers for diagrams to have.

TimeWhen asking questions of when or how, time-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

Arrangement

ArrangementWhen asking questions of what or where, arrangement-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

Context

ContextWhen asking questions of which or why, context-based diagrams are helpful.

Examples:

As you can see each serves different needs and helps answer different types of questions.

By combining the kind of question you’re centering (Time, Context, Arrangement) with the type of model you’re working with (Structural, Process, Behavioral, Conceptual, or Mathematical), you can find the right kind of diagram to help you.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

Diagram x ModelStructuralProcessBehavioralConceptualMathematicalTimeVisual InstructionsGantt ChartTimelineFlow ChartDecision DiagramContextConcept MapJourney MapMental Model DiagramVenn DiagramScatter PlotArrangementSitemapSwim Lane DiagramBlock DiagramQuadrant DiagramBlueprintsApproaching Modeling & DiagrammingEffective modeling involves a thoughtful process:

Set an intention: What do you want this model to accomplish?Research your audience: Who needs to understand this? What do they know already?Choose your scope: What’s included and what’s excluded?Determine scale: How big is the space, and how detailed does this need to be?Iterate and refine: Diagrams are never perfect on the first tryRemember that diagramming is exploratory. You’re trying to make sense of something, so be prepared for your understanding to evolve as you work.

Tips to Getting StartedStart simple: Use basic shapes and lines. Rectangles, circles, and straight lines will get you far.Use a grid: Aligning elements creates visual order that reduces cognitive load.Be consistent: Use the same visual language throughout (don’t mix metaphors).Label everything: Clear labels prevent confusion and questions.Test with others: The only way to know if your diagram helps someone is to test it.Embrace iteration: Your first attempt won’t be perfect, and that’s okay.Don’t overdo it: When it comes to colors, shapes, and decorative elements, less is often more.Hot TakesHere are some opinions I’ve formed over years of diagramming:

There is no such thing as a bad diagram if it helps someone. What matters is effectiveness, not aesthetics.Diagrams made for yourself can look messier than those made for others. Different audiences have different needs.Fancy tools aren’t necessary. Some of the most effective diagrams I’ve made were drawn on napkins or whiteboards.Color-coding should always have a backup. Not everyone perceives color the same way, so don’t rely solely on color to convey meaning.Labels should be as concise as possible. Aim for under 25 characters for most labels.Line crossing is usually avoidable. If your lines need to cross frequently, reconsider your layout.Diagrams can reveal insights that text alone cannot. The act of visualizing information often leads to new understanding.Frequently Asked QuestionsDo I need to be good at drawing to make diagrams?Absolutely not! Diagrams are about clarity, not artistic skill. Simple shapes and lines are all you need.

What’s the best software for diagramming?The one you’re comfortable with. For beginners, I recommend whatever tools you already know—PowerPoint, Google Slides, or even pen and paper work great. As you advance, you might explore dedicated tools.

How do I know if my diagram is good?If it helps someone understand something, it’s a good diagram. Test it with your intended audience and iterate based on their feedback.

What if my diagram gets too complex?That’s a sign you might need multiple diagrams or a different approach. Consider breaking it down into smaller, more focused diagrams.

How much information should I include?Include only what’s necessary to meet your intention. When in doubt, start with less—you can always add more if needed.

Should I make my diagram pretty?Focus on clarity first. Visual appeal can enhance a diagram but should never come at the expense of understanding.

If you want to learn more about my approach to diagramming and modeling, consider attending my workshop on May 16 from 12 PM to 2 PM ET. Blueprint Basics: Making Models That Actually Help — this workshop is free to premium members of the Sensemakers Club along with a new workshop each month. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for our focus area in June – Controlling Vocabularies

The post The Sensemaker’s Guide to Diagramming & Modeling appeared first on Abby Covert, Information Architect.

April 10, 2025

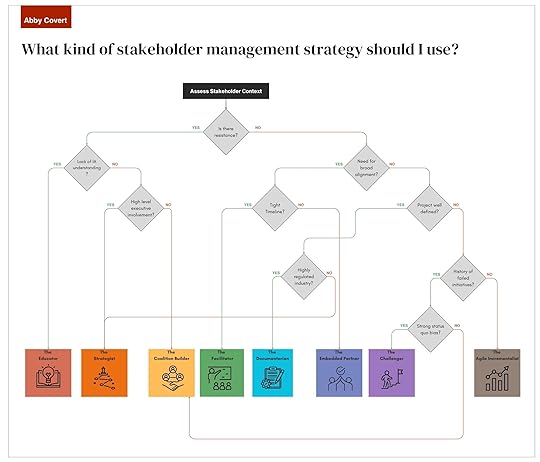

The Sensemaker’s Guide to Stakeholders

If I had a nickel for every time someone told me their information architecture project failed because “the stakeholders just didn’t get it,” I’d have enough money to buy everyone reading this a coffee. Here’s the truth that nobody tells you when you’re learning about IA: the best structure in the world won’t survive contact with misaligned stakeholders.

Think about it. How many brilliant navigation systems have been destroyed by last-minute executive opinions? How many carefully crafted taxonomies have been mangled by committee thinking? How many elegant content models have crashed against the rocks of organizational politics?

The gap between a perfect IA solution and successful implementation isn’t technical – it’s human. And that’s why stakeholder management isn’t a nice-to-have skill; it’s the difference between your work living or dying.

So let’s talk about the part of IA that isn’t about boxes and arrows, but about the people who need to understand, support, and defend those boxes and arrows when it matters most.

This article covers:

Who is a Stakeholder in Sensemaking?A stakeholder is someone who has a viable and legitimate interest in the work you’re doing. Sometimes we choose our stakeholders; other times, we don’t have that luxury. Either way, understanding our stakeholders is crucial to our success. When we work against each other, progress comes to a halt.

Stakeholder management in IA isn’t about manipulating people to get your way. It’s about creating shared understanding and momentum toward making sense of a mess together.

Reasons to Invest in Stakeholder ManagementLet’s be honest – we love the satisfaction of a perfectly structured taxonomy, the elegant simplicity of intuitive navigation, and the quiet power of a well-crafted site map. Given the choice between sketching out another user flow diagram or sitting through a stakeholder meeting filled with competing opinions and office politics, many of us would choose the diagram every time.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: the most beautiful, logically sound information architecture in the world is completely worthless if it never gets implemented. And implementation doesn’t happen through diagrams – it happens through people.

The stakeholders who control budgets, influence decisions, create content, build systems, and ultimately determine whether your carefully crafted solutions ever see the light of day are the difference between theory and practice.

The most successful information architects understand that their job isn’t just to organize information – it’s to organize people around information. This means developing relationships with stakeholders isn’t just a necessary evil or administrative overhead – it’s the foundation that makes everything else possible.

Because: