Ordinary care

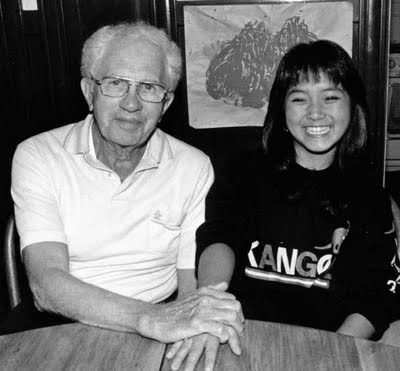

When my dad at age 90 suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed on his left side and unable to swallow, but alert and able to talk, he chose to have his IV removed in order to let nature take its course. He said that he had lived a full life, was ready to die, and didn���t want to be kept alive by machines when his body couldn���t care for itself.

His death took four days. He was not on medication for pain, and by the second day he was unable to speak. By the third day he was unconscious. About thirty minutes before he died, his breathing slowed, with a long pause between each deep breath. I recited psalms and prayed for him, until he was still.

At his memorial service I shared with other family members and friends of my father that I was moved by the way my father faced death. He wasn���t afraid or depressed. He was grateful for his family and for the years he had lived, and he saw accepting his death as a way of expressing his gratitude for the gift of life.

In the university ethics class I teach, I mention my father���s death when we discuss health care, because it illustrates the right of a patient to withhold consent for medical treatment. In the 1990 Cruzan decision the US Supreme Court upheld this right, citing a ���liberty interest��� in the 14th Amendment of the Constitution and the common-law tradition supporting the right not to be touched by another person without consent or legal justification.

International law also supports the right of informed consent, which creates a duty for those providing health care to adequately inform patients of their condition, possible treatment, and their right to consent or decline treatment.

The story of my father���s death illustrates why Catholic moral teaching requires only health care that offers a reasonable hope of benefitting a patient and is not excessively expensive, painful, or inconvenient. This ���ordinary��� care is distinguished from ���extraordinary��� care. Catholic teaching supports using medication for a terminally ill patient to reduce suffering even if this may shorten the patient���s life. For medication is ordinary care and, if it hastens death, this unintended consequence does not outweigh the duty to reasonable means that are not excessively expensive to alleviate suffering.

My father was not Catholic, nor am I. But as a senior now, I support limiting health insurance to coverage for ordinary medical care, and I urge other seniors to do the same for the sake of the common good. We can help those who are younger overcome their fear of death by facing this fear ourselves. We should support health care as a human right for all, which is Catholic teaching and international law as well, but we should also affirm our right to decline medical treatment. And when treatment is very costly and offers only a short-term benefit, why not affirm life by accepting death?

With hope...Bob[image error]

Published on September 12, 2009 16:13

No comments have been added yet.