Remembering Jack Masey

The first thing you noticed was the grin. That great big crooked grin, uninhibited, eyes sparkling, body shaking with laughter about something. It doesn't seem to show up in most of the pictures, but it is how I will always remember him.

I first met Jack in the spring of 2006, interviewing him about his experiences in the WWII unit known as The Ghost Army. The thing that struck me most (after the grin) was how often he used the word “delicious.” And the way he said the word, with such relish. Usually with that wolfish crooked grin. All of life, with its panoply of characters and cultures from the sublime to the ridiculous, it was all a delicious feast for Jack Masey and one he enjoyed with remarkable zest.

I first met Jack in the spring of 2006, interviewing him about his experiences in the WWII unit known as The Ghost Army. The thing that struck me most (after the grin) was how often he used the word “delicious.” And the way he said the word, with such relish. Usually with that wolfish crooked grin. All of life, with its panoply of characters and cultures from the sublime to the ridiculous, it was all a delicious feast for Jack Masey and one he enjoyed with remarkable zest.I can’t believe Jack is gone from this world. As my Ghost Army co-author, Elizabeth Sayles said, “I hoped he would live forever.”

His wife, Beverly, wrote of his “full throated enthusiasms,” and the way he loved people “deeply in that big outrageous Masey-way.” My wife Marilyn called him “the man who invented charm.” Any get-together with Jack was always punctuated by frequent outbursts of laughter—or just frequent outbursts! Rarely have I met anyone who radiated infectious energy and enthusiasm. And believe me, it was delicious.

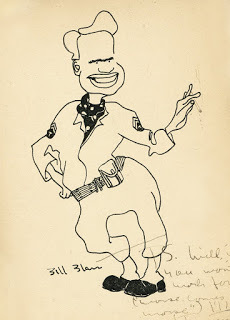

Jack Masey caricature of

Jack Masey caricature of Ghost Army soldier Bill BlassTypical of Jack was the way he viewed his fellow soldiers during WWII. They were delicious too. “I’d only known Brooklynites or Manhattanites. Now suddenly I was thrown in to another world. I’d never met people like this. I thought, ‘My God, I’ve got the raw material out here. I’m going to draw every one of these crazies.’ And I did.” He caricatured every man in his company in a delightful volume he titled You on KP. In the midst of war, in Luxembourg City, he collected money from his buddies arranged to have 150 copies printed, one for every man. For many, it became their most treasured WWII artifact.

Jack viewed his WWII experiences in the Ghost Army as a bit of a lark. “I learned a lot, fooling people, and deceiving people,” he laughed. “And it stood me in good stead my whole life.” But he was also delighted and proud of the attention that the Ghost Army has received in recent years. He called often to find out what the latest was about the documentary, book, movie, and offering lavish praise and enthusiastic support.

After the war Jack went to Yale School of Art and Architecture, (during which time he penned a few caricatures for Esquire), then went to work for the U.S. State Department staging trade exhibits around the world. He was the Chief of Design for the 1959 American exhibition in Moscow that famously became the site of the “kitchen debate.” Nixon and Khrushchev squared off in the kitchen of the exhibit’s model house. The fireworks began when Khrushchev told Nixon he did not believe an average American family could have a kitchen like that. Jack told me he was right. “We widened it a little bit to get a lot people through,” he laughed.

After the war Jack went to Yale School of Art and Architecture, (during which time he penned a few caricatures for Esquire), then went to work for the U.S. State Department staging trade exhibits around the world. He was the Chief of Design for the 1959 American exhibition in Moscow that famously became the site of the “kitchen debate.” Nixon and Khrushchev squared off in the kitchen of the exhibit’s model house. The fireworks began when Khrushchev told Nixon he did not believe an average American family could have a kitchen like that. Jack told me he was right. “We widened it a little bit to get a lot people through,” he laughed. But his amazing career spanned so much more, both while he worked for the government, and later after he founded his own company, Metaform, with designers Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar. Trade exhibits in Kabul, New Delhi, Brussels, Berlin. The American Pavilion at Expo ‘67, the Statue of Liberty Museum, Ellis Island Museum, the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, these are just a few of the many exhibits midwifed by Jack Masey.

Jack didn’t play it safe in his work. When it came to the American Pavilion at Expo 67, he wanted it to be bold, groundbreaking, maybe even “kooky,” to use a word from one of his memos of the time. He worked with some favorite collaborators, such as Chermayeff and Buckminster Fuller. He also brought in some of his Ghost Army buddies to help. He got Bill Blass to design the guide uniforms, displayed some of Ellsworth’s Kelly art, and commissioned a film from Art Kane. The result, according to Michigan State History graduate student Daneila Sheinin, “transformed the ways in which architecture, design and exhibits could come together in a stunning visual end point.”

Jack didn’t play it safe in his work. When it came to the American Pavilion at Expo 67, he wanted it to be bold, groundbreaking, maybe even “kooky,” to use a word from one of his memos of the time. He worked with some favorite collaborators, such as Chermayeff and Buckminster Fuller. He also brought in some of his Ghost Army buddies to help. He got Bill Blass to design the guide uniforms, displayed some of Ellsworth’s Kelly art, and commissioned a film from Art Kane. The result, according to Michigan State History graduate student Daneila Sheinin, “transformed the ways in which architecture, design and exhibits could come together in a stunning visual end point.” With all of his many achievements, and friendships with everyone from Bill Blass to Julia Childs, Jack never took himself too seriously. He could easily have been superior, pretentious or condescending, but I imagine it never occurred to him. Instead, he was a beloved mentor to many. He frequently talked to graduate students interested in his international design work, and high schools students interviewing him about the Ghost Army. To all he showed his patience, good will and enthusiasm.

Jack did not want a public remembrance, which is painful to the many people who would like to have gathered to celebrate and honor him. A skeptic, but not a cynic, he was a man full of optimism and hope for his friends and for the world. Most of all, he was a person who gave enthusiastically of himself to others. Beverly said that Jack suffered from heart failure near the end, but I don’t believe it. His great big heart never failed anyone.

Jack Masey. Delicious.

Jack's obit in the NYT

Published on March 22, 2016 17:41

No comments have been added yet.