Until A Dictator: Lincoln vs. The RISODs

"ONLY A DWARF IN MIND!"

"In looking over the orders I find nothing of moment, save one in which the President commutes the death punishment of all deserters to imprisonment during the war. Poor, weak, well meaning Lincoln!"

—from the diary of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, Chief of Artillery, Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, June 30, 1864

In his dim view of Abraham Lincoln's nerve and competence, Colonel Wainwright was hardly alone among Union officers, men chronically frustrated over the war's prosecution. William Tecumseh Sherman, a colonel in March of 1861, came away exasperated from his first meeting with the new President, judging him naive about what Southern secession meant and the national trauma it would bring. Sherman's take on Lincoln improved over the war's tumultuous course. Still, on the eve of the 1864 Presidential election and ultimate Northern victory, Sherman's core ambivalence remained. "I am almost in despair of popular Government," the general wrote to his brother, Ohio Senator John Sherman, "but if we must be so inflicted I suppose Lincoln is the best choice, but I am not a voter."

On the political side, harsher assessments issued from the Republican left. When Lincoln did not declare immediate Emancipation in the days after Fort Sumter, Abolitionist firebrand William Lloyd Garrison accused him of "unwittingly helping to prolong the war, and to render the result more and more doubtful! If he is 6 feet 4 inches high, he is only a dwarf in mind!" And when Lincoln's year-end message to Congress pledged (vainly, God knows) to prevent the war from becoming "a violent, remorseless revolutionary struggle," Garrison's rancor surged again: "What a wishy-washy message from the President! He has evidently not a drop of anti-slavery blood in his veins."

Frederick Douglass, who would come to admire Lincoln and in the end declare him "emphatically the black man's president," spent much of the war's first half spitting rhetorical nails in his direction. So did that Radical titan Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, of whom historian Allan Nevins wrote, "In brooding over what he regarded as Lincoln's delays and excessive generosity, Stevens sometimes exhibited a frenzy of anger." Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler, a pillar of Abolitionism, declared, "The President is a weak man, too weak for the occasion." And Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden huffed, "If the President had his wife's will and would use it rightly, our affairs would look much better."

Last portrait of Abraham Lincoln, April 10, 1865, four

days before his assassination. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Meanwhile, of course, the political right strafed Lincoln without letup. Despite a soldierly scorn for politics, Colonel Wainwright expressed what many War Democrats thought when he described the President as "completely in the hands of the radicals of his party." Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour of New York, who opposed Lincoln on Emancipation as well as the Draft, accused his administration of "military despotism." Above all there was the virulent Copperhead or Peace Democrat movement, drawing from the North's "doughface" (pro-Southern) element (see https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog...). Reacting to Emancipation, the Draft and the sporadic suspension of habeas corpus, Copperhead spokesmen often made today's Talk Radio hosts sound like the soul of forbearance. Wisconsin editor Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy of the LaCrosse Democrat called Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero," before going on to urge the President's assassination. (It's unknown if Pomeroy noted that these statements did not land him in jail—in time of war, no less.) An Ohio editor stated that the Abolition and conscription agenda of "the despot Lincoln" would bring him "the fate he deserves: hung, shot or burned." And the pre-eminent Copperhead champion, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, excoriated the President as "King Lincoln."

When you are the low-born leader of a country neck-deep in crisis—in its bloodiest war, say, and a Civil one besides—and trying your best to shepherd it through, maneuvering among the varied factions, marshaling governmental powers to meet the challenge, willing to take emergency measures yet mindful of legal precedent, facing fierce enemies both at home and on the battlefield, you will be subject to a whole range of insult. When the war is not going well, as it often won't be, military men will call you meddling and incompetent. Thundering egotists among them—Major General George B. McClellan, for instance—will even refer to you as "an idiot," "a well meaning baboon" and "the original gorilla."

But the most merciless criticism will come from the political sphere, where men of greater wealth and education—men who imagine how much better they would have done in your place—regard you as a rube and see your struggles as their judgment's confirmation. Idealogical allies, impatient with your administration's progress toward cherished goals, will call you soft, spineless, feckless, weak-kneed, a poor leader. And idealogical foes will deliver the opposite charge, calling you a tyrannical monster. A remarkable few might even manage to call you weak and diabolically effective, depending on which feels best at the moment.

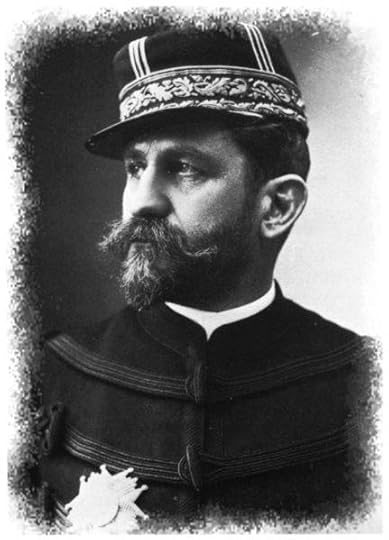

Union Major General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker, partial to dictatorship. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

In Lincoln's case, a lot of this bile came from an understandable horror and frustration over the war. Some of it came from that deep-seated American addiction to moral outrage, or at least the ennobling sound of it, combined with an uncomplicated idea of how much power a President actually has. Some of it came from a shallow commitment to democracy, with its creaky workings, endless debate and the chance that things won't always go your way. Some it came from pure wackjob hysteria, with racial animus as its tinder. And some of it, once in a while, was fair. An activist like Frederick Douglass, for example, could hardly be faulted for chafing over the delays in African American recruitment—which, when it did come about, proved indispensable to victory. Nor could Negro leaders be fairly criticized for rejecting Lincoln's August 1862 proposal of black colonization in Central America. (The eminent historian Eric Foner has, nevertheless, observed that Lincoln's doubts concerning black assimilation arose from his view of white racism as its chief impediment—something that placed him ahead of most whites on that subject.) And Lincoln's military critics were not always off base. During T.J. "Stonewall" Jackson's spring 1862 rampage in the Shenandoah Valley, Lincoln's flurry of orders played into the wily Jackson's ploy to divert Union forces, three of which separately pursued but did not catch him. And given the President's sensitivity to public opinion, he was capable of giving the kind of contradictory order that he gave Ulysses S. Grant at Petersburg, directing him to make a strong attack but keep casualties minimal.

Yet nothing summed up political and military discontent with Lincoln like Major General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker's whiskey-fueled comment in late January, 1863.

"I WILL RISK THE DICTATORSHIP"

Along with the entire Army of the Potomac, corps commander Hooker had just endured that army's latest morale-stomping failure: the Mud March, when General-in-Chief Ambrose E. Burnside tried to cross the Rappahannock and outflank Robert E. Lee, but was thwarted by a three-day rainstorm. Bad luck is unforgivable in a commander—but in mid-December, at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Burnside had shown bad judgment too. Ignoring Hooker's protests, he had thrown wave after wave of Union boys against Lee's defenses on Mayre's Heights and suffered a crushing defeat. Now Hooker, disgusted once more with his superior, castigated him to any who would listen. He also criticized the Union's state of affairs more broadly, and a New York Times reporter relayed the gist of it: "Nothing would go right until we had a dictator, and the sooner the better."

With the Mud March and with discord among his subordinates, Burnside's fortunes were played out and Lincoln named "Fighting Joe" to replace him. It was an obvious and popular choice. Since the Second Seminole and Mexican-American Wars, Hooker had earned his nickname many times over. And since McClellan's Peninsular Campaign the previous spring, he had proven himself a brave and aggressive field commander who cared deeply about his men. At Antietam, his corps hammered the Confederate left and took tremendous casualties, with Hooker himself wounded in the foot. (In my novel Lucifer's Drum, Bartholomew Forbes loses his leg at Antietam while under Hooker's command.) He was also known for hard drinking and prostitutes. Though the general and the term "hooker" have no connection, he certainly made one seem plausible—his headquarters at Falmouth, VA was described as part saloon and part brothel. And a red-light section of Washington, D.C. was called "Hooker's Division" in his honor. He was known too for denigrating fellow generals—chiefly McClellan, whose irrational fears and risk-aversion doomed the Peninsular Campaign and kept him from destroying Lee at Antietam, and Burnside for the Fredericksburg disaster. Hooker was indiscreet—but in those two cases, he was also right.

Having appointed Hooker, Lincoln sent him a letter admonishing him for his efforts to undermine Burnside, "a brother officer" who the President regarded as a good man simply over his head. He also said, more cooly: "I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship."

Over the next three months, however, Hooker revealed himself as a gifted and energetic administrator. His improvements in training, food, sanitation, medical care and the furlough system brought army morale back from the depths and desertions down to a trickle. His creation of the Bureau of Military Information under the capable Colonel George Sharpe (Bart Forbes' superior in Lucifer's Drum) would eventually bear marvelous fruit. His introduction of corps badges promoted pride and made units more identifiable to one another when on the march. Last but not least, his reorganization of the cavalry as a single corps made it more effective against Southern horsemen, who had been so plainly superior thus far. And with the coming of spring, Hooker was able to crow: "I have the finest army on the planet. I have the finest army the sun ever shone on . . . If the enemy does not run, God help them. May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none."

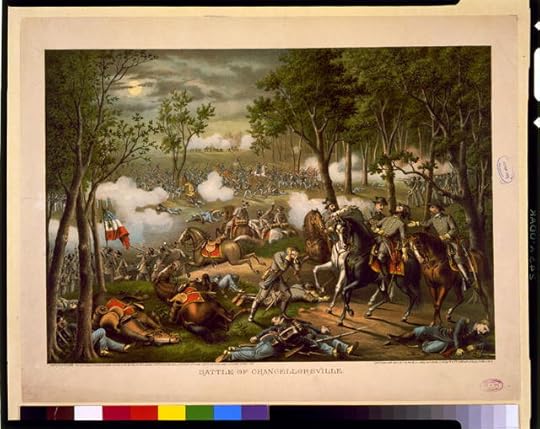

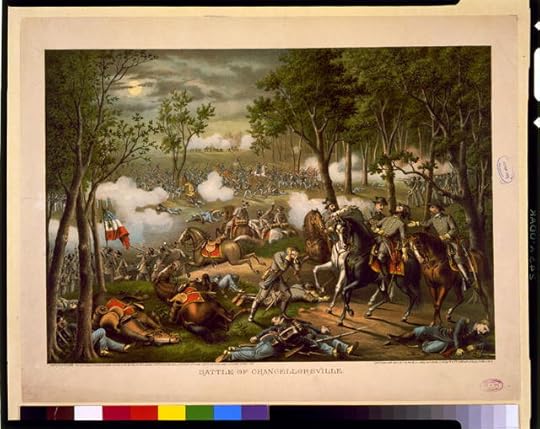

Print from the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863. In right foreground, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson's fatal wounding by his own men. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

CHANCELLORSVILLE: A BOAST DROWNED IN BLOOD

For a present-day American whose sympathies tilt Union, reading about Hooker's dazzling plan to smash Lee—and its dazzling execution, at first—can bring a pang. In late April, screened by cavalry, three of his corps swiftly forded the Rappahannock and the Rapidan, then swung southeast to envelop Lee (whose army totaled less than half of Hooker's 134,000-man behemoth) in the rear and left flank. Two more corps under Major General John Sedjwick remained in front of Fredericksburg to focus Rebel concern; another corps and a division were poised upriver, ready to reinforce either Sedjwick or Hooker's main body. On the evening of April 30, that main body was camped around a crossroads mansion called Chancellorsville, amid a thick second-growth forest called The Wilderness. To his troops, Hooker declared that the enemy "must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him." His cockiness peaked the next day, even as his advancing force hit a solid line of Confederate infantry and artillery. "The rebel army is the legitimate property of the Army of the Potomac," he proclaimed.

But the Confederates' scrappy first response caused something strange to happen, deep inside Hooker. Wondering if enemy strength was greater than had been thought, he hesitated, then withdrew back to Chancellorsville to think things out. In this fateful hour—with the plan working and glory in his grasp—he caught a case of existential vertigo. That same evening, Lee and Stonewall Jackson—two men alien to such vertigo—sat side by side on a cracker box and worked out a spectacular counter-stroke, one that defied all military convention. Jackson with 25,000 men would march wide to the southwest around Hooker's right flank, while Lee with 20,000 continued to fight him in front. The army's remainder would be left on Mayre's Heights to face Sedjwick.

Jackson's march through the tangled growth took most of May 2. When Yankee advance units reported the movement, Hooker decided it was just part of Lee's army in retreat and sent two divisions after it. And that evening, when Jackson launched his Rebel-yell attack on Hooker's oblivious right, there was hell to pay (as depicted through Ben Truly's memory of it in Lucifer's Drum). An entire Union corps was overrun and scattered through the woods. In the savage night's confusion, troops of both sides blindly fired upon their own—and presently, this claimed Jackson himself. Mistaking his party for Yankee cavalry, a North Carolina unit raked it with fire and wounded the great general. His left arm amputated, Jackson survived a week before dying of pneumonia, to the lasting sorrow of Lee and the non-enslaved South.

One more gaping fact eluded Hooker and his staff on the morning of May 3: in the face of superior numbers, Lee had daringly split his main force in two. A more engaged commander would have grasped this and ordered an attack from the Union-held high ground at Hazel Grove, driving between the two halves and destroying them in turn. But in his mental paralysis, Hooker gave no such order. Instead he let Lee capture Hazel Grove and reunite his forces, which converged on Chancellorsville as the lumbering Union retreat began. Lee arrived on the scene to the wild cheers of his victorious, powder-blackened troops. Back at Fredericksburg, meanwhile, Sedjwick crossed the Rappahannock and successfully stormed Mayre's Heights, accomplishing what Burnside had so sadly failed to do in December. But he then dallied as General Jubal A. Early (a major character in Lucifer's Drum) conducted a stiff fighting retreat, preventing Sedjwick from coming to Hooker's aid. So ended the second bloodiest day in U.S. history (21,357 casualties), next to Antietam. And so ended Joe Hooker's dream of being the Union's savior.

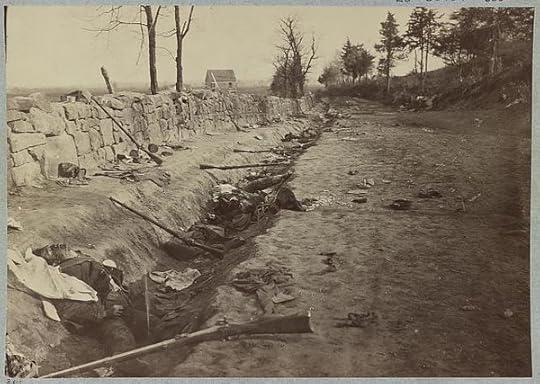

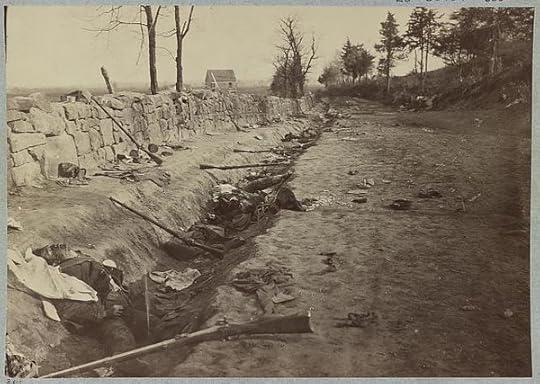

Confederate dead at Mayre's Heights, Fredericksburg, VA, May 3, 1863. This photo was

taken some fifteen minutes after Union troops successfully stormed the infamous stone wall. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the next few days, the battered Army of the Potomac withdrew north of the Rappahannock and Lee retook Fredericksburg. Absorbing yet another calamity, Lincoln lamented: "My God, my God, what will the country say?" His close friend, reporter Noah Brooks, said, "Never, as long as I knew him, did he seem to be so broken up, so dispirited, and so ghostlike." Chancellorsville was called Lee's "perfect battle"—a description made plausible only when considering what would have happened to his army, had his gamble not paid off. The South could ill afford the high casualties he sustained, and no one could fill Stonewall Jackson's boots. (The first thing I ever read on Chancellorsville was a book aptly subtitled "Defeat In Victory.")

In mid-June, Lee marched his Army of Northern Virginia over the Blue Ridge and down the Shenandoah, beginning the invasion that would culminate in the three-day epic of Gettysburg. Hooker, still in command, wanted to use the chance to seize Richmond; Lincoln, who knew that destroying Lee and not capturing any city would bring victory, nixed the idea. It was a telling moment. Since Chancellorsville, Hooker's position had been shaky—his second-in-command, Major General Darius N. Couch, had even refused to continue serving under him. Shadowing the enemy while trying to shield Washington and Baltimore, Hooker fell into a relatively minor dispute with Army Headquarters and offered his resignation. Lincoln immediately accepted it, replacing him with the waspish but competent Major General George G. Meade on June 28.

"THE PRESIDENT SEEMED TO THINK HIM A LITTLE CRAZY"

So what the devil happened to Hooker at Chancellorsville? Reportedly he had given up whiskey for the campaign; some have suggested that from a psychological standpoint, it was exactly the wrong time to abandon the routine of liquid courage. Others have pointed to the crucial morning of May 3 at Hooker's headquarters, when a Rebel cannonball struck the pillar that he was leaning against, knocking him out for an hour. Suffering a concussion, he nonetheless refused to pass command to General Couch. But I think Hooker's basic problem was one he shared with all men who run primarily on bluster—a propellent that takes them only so far, past which a fundamental insecurity begins to surface and cripple their brains.

Apart from all that, though, we have to wonder: When Hooker asserted the country's need for a dictator, did he envision himself in that role? The authoritarian, the strongman, the "man on horseback?" Rising out of the turmoil to talk straight and point the way? To slash through all the red tape, legal niceties and prissy caveats? To kick ass and take names? To save the country? It's a sort of figure we've come to know on a global scale. Republican government was still relatively new in the American Civil War era—and to many, a dubious proposition. Cold aristocratic eyes gazed from Europe, willing the United States to tear itself apart and disprove its own precepts.

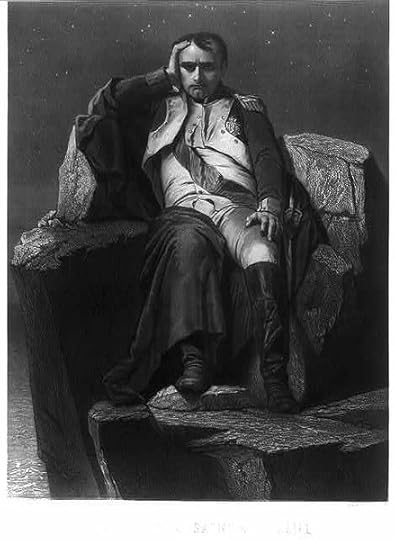

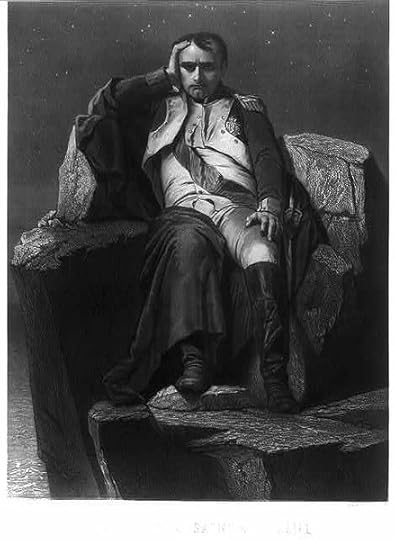

Generally defined, authoritarianism was history's ancient norm, by way of kings, queens and warlords. But a more modern and specific definition was dawning. Napoleon Bonaparte, revered by Northern and Southern military men alike, had already set the template. He was the daring upstart, the bold usurper, the national unifier, the martial genius—France's emperor not by lineage but by his own ambition, as well as the French people's acclaim. He premiered the characteristic central figure of authoritarianism, the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny—or RISOD, as I'll refer to it from here on. To an extent, Fighting Joe fit the self-styled RISOD bill. He had the swagger, the grandiosity, the braggadocio. He was a clever man of action, blazingly free in his belittlement of others.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), Emperor of France, template

for the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny, or RISOD.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But if there was one contemporary who met RISOD specs even more, it was another man whom Hooker had served under and come to despise: George Brinton McClellan, once hailed by Northern newspapers as the "Young Napoleon Of The West." On the heels of the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, 34-year-old Major General McClellan had arrived in Washington in late July, 1861, having scored two minor victories in western Virginia. Born of a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia family, he had graduated second in his class at West Point and served with distinction, even representing the U.S. as an observer in the Crimean War. He then had a creditable run in civilian life, as an official with the Illinois Central and the Ohio & Mississippi Railroads. Except for the malaria he contracted in the Mexican-American War, this was someone who had led a charmed life, without one major personal or professional setback.

The term "narcissist" had not yet been coined, but we may safely view Little Mac through that lens. A high proportion of talented narcissists achieve prominence in public life—and while all of us fall somewhere on the pathology spectrum, this sort of person is essentially different. Still, just an elite few qualify for full-on RISOD status. To call them "arrogant" falls breathtakingly short and is somehow beside the point, like dwelling on how cold it is at the South Pole. Confronted with their stratospheric self-regard, a regular sane person can only smile, maintain eye contact and slowly back out of the room. It is no wonder that presidential secretary John Hay said of Lincoln (a man who'd had plenty of setbacks in life), "The President seemed to think him {McClellan} a little crazy." And who's to say it wasn't a kind of crazy? Often enough, it sure looked that way.

QUAKER GUNS AND CIRCULAR MARCHING

To read McClellan's series of humblebrags to his worshipful wife (and what other kind of wife would a guy like this have?) is to face a choice: do you laugh or puke? But let's get it over with: "God has placed a great work in my hands . . . The people call upon me to save the country—I must save it & cannot respect anything that is in the way . . . I find myself in a new and strange position here—Presdt, Cabinet, Genl Scott & all deferring to me—by some strange operation of magic I seem to have become the power of the land . . . I almost think that were I to win some small success now I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me—but nothing of that kind would please me—therefore I won't be Dictator. Admirable self-denial!" Jesus Christ make him stop.

{For a magnificent cry-from-the-heart concerning the Young Napoleon, I recommend Mallory Ortberg's "Yellin' About McClellan" commentary in The Toast (http://the-toast.net/2014/03/24/i-hat...). And there's Bob Simpson's glorious installment in Crazytown, "McClellan Was An Asshole" (http://www.crazytownblog.com/crazytow...). Both pieces were inspired by their authors' reading Doris Kearns Goodwin's monumental Team Of Rivals: The Political Genius Of Abraham Lincoln.}

Of Little Mac's dispiriting tenure with the Army of the Potomac, here is a thumbnail version: There were his superb organizational skills that worked wonders on the army, whose men generally idolized him—but also, starting early, his wildly inflated estimates of enemy troop strength, while his own army's numbers were in fact much greater. And there was his public disdain for black people and Abolitionists (After the war, he would write, "I confess a prejudice in favor of my own race, & can't learn to like the odor of either Billy goats or niggers"); his friction with the aging general-in-chief, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott—a truly great soldier, whose ouster and title McClellan soon secured; his endless dithering, which let Confederate General Joseph Johnston's army slip away from Manassas and leave behind its "Quaker guns"—logs painted black, fake cannon used to dupe Yankee eyes; his loathing of Lincoln and other federal officials, even as they strove to meet his bottomless demands for men and materiel, and whose entreaties for action sent him on rants ("If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time," said the frustrated Lincoln.)

Major General George B. McClellan—superb organizer,

supreme egotist, poor fighter—with his wife Mary

Ellen Marcy McClellan. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

And there was his spring 1862 offensive up the Peninsula, devolving into a massive snail's creep toward Richmond—while in McClellan's mind, the detective Allan Pinkerton's sloppy intelligence-gathering further magnified the enemy's size, as did some clever Confederate fakery (In Lucifer's Drum, Nathaniel Truly recounts how the Rebs marched in circles to make their Yorktown garrison seem much bigger than it was—and how his boss Pinkerton rejected this report, prompting Truly's cussing resignation); within shouting distance of the Confederate capital—his much faster withdrawal, his nerves unravelling in the Seven Days' Battles; his refusal to reinforce Major General John Pope, one factor in the latter's rout at Second Bull Run; at last, the tragedy of the Maryland Campaign, when he failed to exploit the discovery that Lee's forces were split in four (as revealed in the infamous "Lost Order")—and in the blood-soaked clash at Antietam (September 17, 1862), when he refused to commit his reserves and finish off the outnumbered Lee. On November 5, Lincoln finally sacked him and put in Burnside. In the Presidential race two years later, God called McClellan to "save the country" yet again by running against Lincoln—but Lincoln and the country whomped him, in ungodly fashion.

McCLELLAN'S BODY GUARD

"Self-esteem: an erroneous opinion of oneself."—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary

In the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny, along with the knightly poses and planet-sized self-esteem, with all the God talk and/or Destiny talk, with the flag-draped appeals to "greatness" and "toughness" and "nerve" and "will" (see Triumph Of The), there is a deep well of contempt for others. It is part of what drives him, intensifying as he encounters disagreement and other human obstacles—which, like the authoritarianism he embodies, the RISOD is just not built to tolerate. For him it guarantees chronic rage: how can other people be so stupid, so unpatriotic, such losers? But when things go really bad for him, there is an even deeper well that he draws upon, of self-pity. Self-pity is what Mao Tse Tung reflexively fell into when other Communist Party officials curtailed his power in the early 1960's, after his Great Leap Forward had triggered famine and claimed millions of Chinese lives. (He would later wreak grand-scale RISOD revenge on those officials, when he and his wife launched the ruinous Cultural Revolution.) And self-pity was as much Hitler's refuge as his Berlin bunker in 1945, when he issued the "Nero Decree"—a scorched-earth order to destroy all remaining German industry, transport and supplies—the German people having proven themselves unworthy of him. Reichsminister Albert Speer fortunately disobeyed the order.

But the most central RISOD characteristic, the one that feeds all the others like a vast noxious reservoir, is his relationship with reality. When it comes to truth-telling, the RISOD cuts himself all kinds of slack—because if he is divinely favored, if his cause is by definition just and holy, isn't he right to do or say whatever it takes? Yet at a certain point, it becomes moot whether he is consciously lying or propounding an actual belief, since he sees just what his self-flattering conclusions require him to see. He maintains what amounts to an alternate universe. When it comes to convincing others, the RISOD has the advantage of utterly believing his own propaganda, even if he knows he's fudging the specifics a bit. It's how he's able to conceive himself as a popular hero, conflating his own will with that of The People.

And this talent isn't just an abstract thing. Like a hallucinatory drug, it can edit real-life experience into whatever the RISOD wants. In a letter to his wife, McClellan oozed pity as he recounted the departure of his erstwhile superior and antagonist Winfield Scott: "It was a feeble old man scarce able to walk—hardly any one there to see him off but his successor." But according to the newspapers, a large crowd had gathered at the rail depot to wish Scott a fond farewell, along with both generals' staff members, a cavalry escort and two cabinet secretaries—in a pre-dawn downpour, no less. "Memory is a gentleman," they say—but to McClellan's vanity, it was a slave.

Armed with this pliant view of reality, the RISOD may indulge another of his important traits: blame deflection. (In this area, Napoleon actually seems a cut above the wannabes he spawned, if it's true that he said, "I have been mistaken so often, I no longer blush for it.") McClellan was typical of the breed. Like any general's, his orders implicitly urged personal responsibility on the part of subordinates and government functionaries, who he was quick to blame for whatever went wrong. But God forbid that anyone dare call him to account. When his troops under Brigadier General Charles P. Stone were shattered at Ball's Bluff, the worst decisions of that day (Oct. 21, 1861) were not McClellan's—but he was guilty of poor communication. Still he let the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War scapegoat Stone, who was arrested and imprisoned.

To his wife, McClellan wrote, "The whole thing took place some 40 miles from here without my orders or knowledge. It was entirely unauthorized by me & I am in no manner responsible for it." Had that even been true, an overall commander is supposed to take responsibility for any major action that happens on his watch—but this was the opposite of a stand-up guy. On the Peninsula months later, withdrawing before an enemy half the size that he imagined, McClellan telegraphed Secretary of War Stanton thus: "I have lost this battle because my force was too small. I again repeat that I am not responsible for this . . . If I save this army now, I tell you plainly I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army." I find it hard not to see this capacity for denial as essential cowardice.

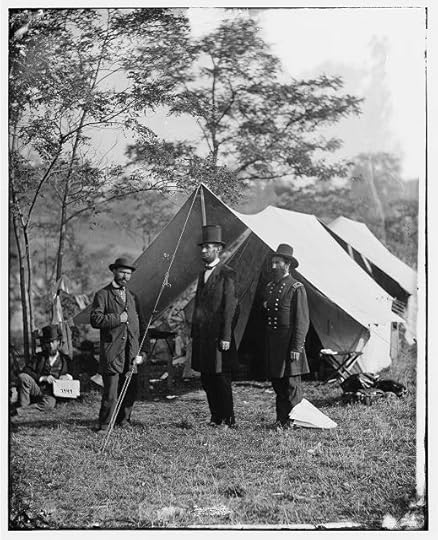

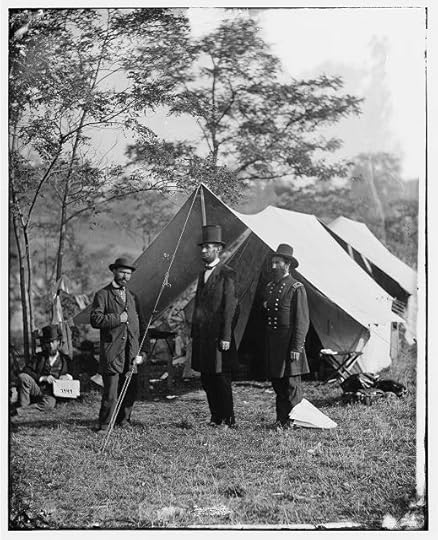

Lincoln visiting the Army of the Potomac at Antietam, October 3,

1862, posed with Major General John A. McClernand (right) and

chief detective Allan Pinkerton (left). (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

"Cowardice" is an awfully easy word to throw around, especially for a 21st-Century noncombatant and non-politician. Still, when you look at the RISOD's self-image and public image and then at the recorded facts, the ironies just won't quit. For instance: so much of his sales pitch is about decisiveness—the bracing clarity it brings, the banishment of doubt. It can play well for a time, if enough people are convinced to indulge their black-and-white thinking—some who have reservations might even say, "Well, at least he's decisive. A Leader." But what looks/sounds like decisiveness can end up being mere dismissiveness in disguise—a lazy reflex, and one that bears a striking resemblance to stupidity. It always brings trouble. And as trouble mounts and pressure grows, beneath all the iron certainty, a worm of doubt starts eating away. Doubt, all the more ravenous for its long suppression.

Failure doesn't necessarily follow—the public-image juggernaut can take its owner quite a distance, on sheer momentum. No less a RISOD paragon than Hitler was called (behind his back) a Teppichfresser, a "carpet-eater," owing to his paroxysms of rage when major decisions weighed on him and he could make no call. Journalist and historian William L. Shirer glimpsed Hitler in the midst of the 1938 Munich Crisis and wrote, "he seemed to be on the edge of a nervous breakdown," with physical tics and a look of insomnia. Munich resulted in a great expansionist coup for the Feuhrer, with France and England backing down before his threats. Yet in the war that commenced a year later, at such crucial points as the Normandy Invasion, his high-strung indecisiveness would doom the Nazi cause.

The RISOD cult also has much to do with physical bravery. Its poster boys may in fact show flashes of this in their youth—but as they rise in the world, as the loss of their wondrous selves becomes a harder and harder thought to bear, an obsession with personal safety overtakes them. Threats surely do exist—these are controversial men, after all, who stir up hatred and become targets thereby. If you are someone on the scale of Hitler or Stalin, an enflamed paranoia will even prove sensible—because they definitely are out to get you. But in most cases, the fear is disproportionate—enough to hurt the RISOD's strutting sense of Destiny, as well as his job performance. In his 1922 power-grabbing March On Rome, Benito Mussolini had photos taken of himself marching alongside black-shirted fellow fascists, then high-tailed it back to Milan to see how the confrontation unfolded, far from its danger. Twenty or so years later, when he visited Axis forces in North Africa, German soldiers disdainfully noted his unwillingness to go anywhere near the action.

And McClellan, who shared Il Duce's sense of self-worth? He kept his headquarters far behind the battlefront—on the Peninsula and also at Antietam, so far that it hampered his awareness of events. During the Battle of Malvern Hill (July 1, 1862), McClellan stayed safely aboard a gunboat on the James River while his rear guard repelled the pursuing Rebels. "I must not unnecessarily risk my life," he wrote to his wife, "—for the fate of my army depends on me & they all know it." (For the love of God, Mrs. M., didn't you ever get tired of this??) In his gripping and masterful Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, historian Stephen W. Sears writes of how McClellan hated to lose a single soldier. Compassion—something I'm sure the general was capable of feeling—can be inferred. But as a dominant factor, something else deserves consideration.

It's the nature of the narcissist, the megalomaniac, the RISOD, to see other people as just an extension of himself. Friends, spouses, children—armies. In the Army of the Potomac—that magnificent machine that he had built—how could McClellan not see such a giant self-extension? And how could he not react with horror at its maiming, real or potential? President Lincoln was on to something when, during his visit to the army two weeks after Antietam (and one month before McClellan's dismissal), he gestured toward the legion tents and asked his companion, Illinois Secretary of State Ozias M. Hatch, "Hatch, what is all this?" Hatch replied, "Why, Mr. Lincoln, this is the Army of the Potomac." And Lincoln responded: "No, Hatch, no. This is General McClellan's body-guard."

"LET US BE VIGILANT, BUT KEEP COOL"

In the end, of course, it was neither McClellan nor any other RISOD who vanquished the Confederacy. That achievement, more than any two figures, belonged to Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant—men of modest bearing, grounded and confident but without bravado. Each absorbed the pain of disaster with an unclouded mind. Each seemed uncannily suited to the trial—Lincoln in particular, as has often been said. Under enormous pressure, he had the judgment to resist the tidal pull of authoritarianism, to push the Constitutional envelope without tearing it. With a priceless combination of skill and principle, he was able to launch Emancipation (at some political cost) and then the Thirteenth Amendment, chattel slavery's tombstone. He had the steady temperament for crises. When Jubal Early's Raid (the pivotal historic event for Lucifer's Drum) threatened D.C. and Baltimore, he kept his public words calm and simple: "Let us be vigilant, but keep cool." His multiple strengths made him an ideal vessel for the nation's suffering. In his last photographic portrait, four days before his murder, we behold the majestic ruin of a man—sandblasted by sorrow and strain, yet with his soul entirely there.

In 1888-89, France saw the sudden rise of general and politician Georges Ernest Boulanger. The nation was in turmoil, though nothing that approached what the United States had faced some 25 years earlier, or what France itself had faced after its defeat by Germany in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Boulanger was a populist hero, a bellicose patriot with strong support among monarchists and traditional Catholics, as well as the working class. In his time as War Minister, his advocacy of revenge against Germany earned him the name General Revanche (Revenge) and—no surprise—the backing of Bonapartists. A literal "man on horseback" (his horse was black and picturesque), he cut a dashing figure despite his poor oratory and vague ideas. The song "Boulanger Is The One We Need" whipped up excitement for him and the movement he led—Boulangisme, a patchwork of political elements that reviled the republican government, tilting conservative and authoritarian overall.

The government fought but could not stop his election to the Chamber of Deputies, representing Paris. Immediately after this (January 27, 1889), partisans urged him to lead a coup d'etat and become military dictator. It seemed imminent. But seized by indecision, Boulanger took shelter at the house of his mistress and could not be found. His magic moment having passed, the government brought charges of conspiracy and treason against him—and to the shock of his followers, he fled the country. In September 1891, at a Brussels cemetery, Boulanger stood over the grave of his recently deceased mistress and shot himself in the head.

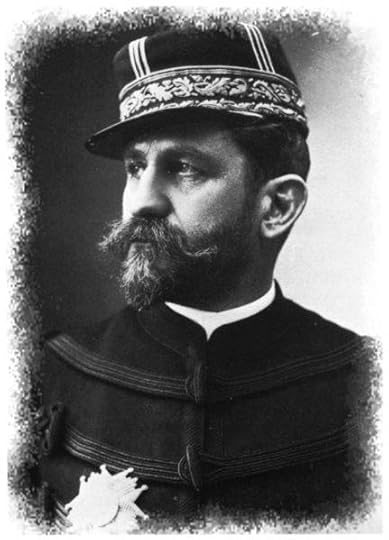

General Georges Ernest Boulanger (1837-91), would-be

political savior of France. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

I offer Boulanger as a chance to marvel—that in its worst four years, despite everything, the United States experienced no similar close call. I offer him too as an example of boilerplate RISOD. Like McClellan, Boulanger was far from the worst of his kind, in part because he failed. For the worst of them, for the truly successful Rugged Individualist Supermen Of Destiny, we look to the 20th Century: the more focused isms, the more artful disinformation, the midnight purges and secret police, the gulags and extermination camps and wars of conquest. But in history's rearview mirror, viewed simply as men, they all look less like messiahs and more like preening blowhards—loud but small, clownish, strangely weak.

Americans should avoid self-congratulation on never having had such a figure in highest office—because there have been some pretty ruthless occupants, regardless. Besides, it could just be more of our relative good fortune—that the right events haven't yet collided within the right state of decay. Because whenever people pour into ideological cul de sacs, when they care less about facts than about how they feel, when demagoguery goes mainstream, and when what Joan Didion called "the thin whine of hysteria" is constant, the RISOD peril looms large. Yuge, in fact.

"In looking over the orders I find nothing of moment, save one in which the President commutes the death punishment of all deserters to imprisonment during the war. Poor, weak, well meaning Lincoln!"

—from the diary of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, Chief of Artillery, Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, June 30, 1864

In his dim view of Abraham Lincoln's nerve and competence, Colonel Wainwright was hardly alone among Union officers, men chronically frustrated over the war's prosecution. William Tecumseh Sherman, a colonel in March of 1861, came away exasperated from his first meeting with the new President, judging him naive about what Southern secession meant and the national trauma it would bring. Sherman's take on Lincoln improved over the war's tumultuous course. Still, on the eve of the 1864 Presidential election and ultimate Northern victory, Sherman's core ambivalence remained. "I am almost in despair of popular Government," the general wrote to his brother, Ohio Senator John Sherman, "but if we must be so inflicted I suppose Lincoln is the best choice, but I am not a voter."

On the political side, harsher assessments issued from the Republican left. When Lincoln did not declare immediate Emancipation in the days after Fort Sumter, Abolitionist firebrand William Lloyd Garrison accused him of "unwittingly helping to prolong the war, and to render the result more and more doubtful! If he is 6 feet 4 inches high, he is only a dwarf in mind!" And when Lincoln's year-end message to Congress pledged (vainly, God knows) to prevent the war from becoming "a violent, remorseless revolutionary struggle," Garrison's rancor surged again: "What a wishy-washy message from the President! He has evidently not a drop of anti-slavery blood in his veins."

Frederick Douglass, who would come to admire Lincoln and in the end declare him "emphatically the black man's president," spent much of the war's first half spitting rhetorical nails in his direction. So did that Radical titan Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, of whom historian Allan Nevins wrote, "In brooding over what he regarded as Lincoln's delays and excessive generosity, Stevens sometimes exhibited a frenzy of anger." Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler, a pillar of Abolitionism, declared, "The President is a weak man, too weak for the occasion." And Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden huffed, "If the President had his wife's will and would use it rightly, our affairs would look much better."

Last portrait of Abraham Lincoln, April 10, 1865, four

days before his assassination. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Meanwhile, of course, the political right strafed Lincoln without letup. Despite a soldierly scorn for politics, Colonel Wainwright expressed what many War Democrats thought when he described the President as "completely in the hands of the radicals of his party." Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour of New York, who opposed Lincoln on Emancipation as well as the Draft, accused his administration of "military despotism." Above all there was the virulent Copperhead or Peace Democrat movement, drawing from the North's "doughface" (pro-Southern) element (see https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog...). Reacting to Emancipation, the Draft and the sporadic suspension of habeas corpus, Copperhead spokesmen often made today's Talk Radio hosts sound like the soul of forbearance. Wisconsin editor Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy of the LaCrosse Democrat called Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero," before going on to urge the President's assassination. (It's unknown if Pomeroy noted that these statements did not land him in jail—in time of war, no less.) An Ohio editor stated that the Abolition and conscription agenda of "the despot Lincoln" would bring him "the fate he deserves: hung, shot or burned." And the pre-eminent Copperhead champion, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, excoriated the President as "King Lincoln."

When you are the low-born leader of a country neck-deep in crisis—in its bloodiest war, say, and a Civil one besides—and trying your best to shepherd it through, maneuvering among the varied factions, marshaling governmental powers to meet the challenge, willing to take emergency measures yet mindful of legal precedent, facing fierce enemies both at home and on the battlefield, you will be subject to a whole range of insult. When the war is not going well, as it often won't be, military men will call you meddling and incompetent. Thundering egotists among them—Major General George B. McClellan, for instance—will even refer to you as "an idiot," "a well meaning baboon" and "the original gorilla."

But the most merciless criticism will come from the political sphere, where men of greater wealth and education—men who imagine how much better they would have done in your place—regard you as a rube and see your struggles as their judgment's confirmation. Idealogical allies, impatient with your administration's progress toward cherished goals, will call you soft, spineless, feckless, weak-kneed, a poor leader. And idealogical foes will deliver the opposite charge, calling you a tyrannical monster. A remarkable few might even manage to call you weak and diabolically effective, depending on which feels best at the moment.

Union Major General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker, partial to dictatorship. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

In Lincoln's case, a lot of this bile came from an understandable horror and frustration over the war. Some of it came from that deep-seated American addiction to moral outrage, or at least the ennobling sound of it, combined with an uncomplicated idea of how much power a President actually has. Some of it came from a shallow commitment to democracy, with its creaky workings, endless debate and the chance that things won't always go your way. Some it came from pure wackjob hysteria, with racial animus as its tinder. And some of it, once in a while, was fair. An activist like Frederick Douglass, for example, could hardly be faulted for chafing over the delays in African American recruitment—which, when it did come about, proved indispensable to victory. Nor could Negro leaders be fairly criticized for rejecting Lincoln's August 1862 proposal of black colonization in Central America. (The eminent historian Eric Foner has, nevertheless, observed that Lincoln's doubts concerning black assimilation arose from his view of white racism as its chief impediment—something that placed him ahead of most whites on that subject.) And Lincoln's military critics were not always off base. During T.J. "Stonewall" Jackson's spring 1862 rampage in the Shenandoah Valley, Lincoln's flurry of orders played into the wily Jackson's ploy to divert Union forces, three of which separately pursued but did not catch him. And given the President's sensitivity to public opinion, he was capable of giving the kind of contradictory order that he gave Ulysses S. Grant at Petersburg, directing him to make a strong attack but keep casualties minimal.

Yet nothing summed up political and military discontent with Lincoln like Major General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker's whiskey-fueled comment in late January, 1863.

"I WILL RISK THE DICTATORSHIP"

Along with the entire Army of the Potomac, corps commander Hooker had just endured that army's latest morale-stomping failure: the Mud March, when General-in-Chief Ambrose E. Burnside tried to cross the Rappahannock and outflank Robert E. Lee, but was thwarted by a three-day rainstorm. Bad luck is unforgivable in a commander—but in mid-December, at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Burnside had shown bad judgment too. Ignoring Hooker's protests, he had thrown wave after wave of Union boys against Lee's defenses on Mayre's Heights and suffered a crushing defeat. Now Hooker, disgusted once more with his superior, castigated him to any who would listen. He also criticized the Union's state of affairs more broadly, and a New York Times reporter relayed the gist of it: "Nothing would go right until we had a dictator, and the sooner the better."

With the Mud March and with discord among his subordinates, Burnside's fortunes were played out and Lincoln named "Fighting Joe" to replace him. It was an obvious and popular choice. Since the Second Seminole and Mexican-American Wars, Hooker had earned his nickname many times over. And since McClellan's Peninsular Campaign the previous spring, he had proven himself a brave and aggressive field commander who cared deeply about his men. At Antietam, his corps hammered the Confederate left and took tremendous casualties, with Hooker himself wounded in the foot. (In my novel Lucifer's Drum, Bartholomew Forbes loses his leg at Antietam while under Hooker's command.) He was also known for hard drinking and prostitutes. Though the general and the term "hooker" have no connection, he certainly made one seem plausible—his headquarters at Falmouth, VA was described as part saloon and part brothel. And a red-light section of Washington, D.C. was called "Hooker's Division" in his honor. He was known too for denigrating fellow generals—chiefly McClellan, whose irrational fears and risk-aversion doomed the Peninsular Campaign and kept him from destroying Lee at Antietam, and Burnside for the Fredericksburg disaster. Hooker was indiscreet—but in those two cases, he was also right.

Having appointed Hooker, Lincoln sent him a letter admonishing him for his efforts to undermine Burnside, "a brother officer" who the President regarded as a good man simply over his head. He also said, more cooly: "I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship."

Over the next three months, however, Hooker revealed himself as a gifted and energetic administrator. His improvements in training, food, sanitation, medical care and the furlough system brought army morale back from the depths and desertions down to a trickle. His creation of the Bureau of Military Information under the capable Colonel George Sharpe (Bart Forbes' superior in Lucifer's Drum) would eventually bear marvelous fruit. His introduction of corps badges promoted pride and made units more identifiable to one another when on the march. Last but not least, his reorganization of the cavalry as a single corps made it more effective against Southern horsemen, who had been so plainly superior thus far. And with the coming of spring, Hooker was able to crow: "I have the finest army on the planet. I have the finest army the sun ever shone on . . . If the enemy does not run, God help them. May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none."

Print from the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863. In right foreground, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson's fatal wounding by his own men. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

CHANCELLORSVILLE: A BOAST DROWNED IN BLOOD

For a present-day American whose sympathies tilt Union, reading about Hooker's dazzling plan to smash Lee—and its dazzling execution, at first—can bring a pang. In late April, screened by cavalry, three of his corps swiftly forded the Rappahannock and the Rapidan, then swung southeast to envelop Lee (whose army totaled less than half of Hooker's 134,000-man behemoth) in the rear and left flank. Two more corps under Major General John Sedjwick remained in front of Fredericksburg to focus Rebel concern; another corps and a division were poised upriver, ready to reinforce either Sedjwick or Hooker's main body. On the evening of April 30, that main body was camped around a crossroads mansion called Chancellorsville, amid a thick second-growth forest called The Wilderness. To his troops, Hooker declared that the enemy "must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him." His cockiness peaked the next day, even as his advancing force hit a solid line of Confederate infantry and artillery. "The rebel army is the legitimate property of the Army of the Potomac," he proclaimed.

But the Confederates' scrappy first response caused something strange to happen, deep inside Hooker. Wondering if enemy strength was greater than had been thought, he hesitated, then withdrew back to Chancellorsville to think things out. In this fateful hour—with the plan working and glory in his grasp—he caught a case of existential vertigo. That same evening, Lee and Stonewall Jackson—two men alien to such vertigo—sat side by side on a cracker box and worked out a spectacular counter-stroke, one that defied all military convention. Jackson with 25,000 men would march wide to the southwest around Hooker's right flank, while Lee with 20,000 continued to fight him in front. The army's remainder would be left on Mayre's Heights to face Sedjwick.

Jackson's march through the tangled growth took most of May 2. When Yankee advance units reported the movement, Hooker decided it was just part of Lee's army in retreat and sent two divisions after it. And that evening, when Jackson launched his Rebel-yell attack on Hooker's oblivious right, there was hell to pay (as depicted through Ben Truly's memory of it in Lucifer's Drum). An entire Union corps was overrun and scattered through the woods. In the savage night's confusion, troops of both sides blindly fired upon their own—and presently, this claimed Jackson himself. Mistaking his party for Yankee cavalry, a North Carolina unit raked it with fire and wounded the great general. His left arm amputated, Jackson survived a week before dying of pneumonia, to the lasting sorrow of Lee and the non-enslaved South.

One more gaping fact eluded Hooker and his staff on the morning of May 3: in the face of superior numbers, Lee had daringly split his main force in two. A more engaged commander would have grasped this and ordered an attack from the Union-held high ground at Hazel Grove, driving between the two halves and destroying them in turn. But in his mental paralysis, Hooker gave no such order. Instead he let Lee capture Hazel Grove and reunite his forces, which converged on Chancellorsville as the lumbering Union retreat began. Lee arrived on the scene to the wild cheers of his victorious, powder-blackened troops. Back at Fredericksburg, meanwhile, Sedjwick crossed the Rappahannock and successfully stormed Mayre's Heights, accomplishing what Burnside had so sadly failed to do in December. But he then dallied as General Jubal A. Early (a major character in Lucifer's Drum) conducted a stiff fighting retreat, preventing Sedjwick from coming to Hooker's aid. So ended the second bloodiest day in U.S. history (21,357 casualties), next to Antietam. And so ended Joe Hooker's dream of being the Union's savior.

Confederate dead at Mayre's Heights, Fredericksburg, VA, May 3, 1863. This photo was

taken some fifteen minutes after Union troops successfully stormed the infamous stone wall. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the next few days, the battered Army of the Potomac withdrew north of the Rappahannock and Lee retook Fredericksburg. Absorbing yet another calamity, Lincoln lamented: "My God, my God, what will the country say?" His close friend, reporter Noah Brooks, said, "Never, as long as I knew him, did he seem to be so broken up, so dispirited, and so ghostlike." Chancellorsville was called Lee's "perfect battle"—a description made plausible only when considering what would have happened to his army, had his gamble not paid off. The South could ill afford the high casualties he sustained, and no one could fill Stonewall Jackson's boots. (The first thing I ever read on Chancellorsville was a book aptly subtitled "Defeat In Victory.")

In mid-June, Lee marched his Army of Northern Virginia over the Blue Ridge and down the Shenandoah, beginning the invasion that would culminate in the three-day epic of Gettysburg. Hooker, still in command, wanted to use the chance to seize Richmond; Lincoln, who knew that destroying Lee and not capturing any city would bring victory, nixed the idea. It was a telling moment. Since Chancellorsville, Hooker's position had been shaky—his second-in-command, Major General Darius N. Couch, had even refused to continue serving under him. Shadowing the enemy while trying to shield Washington and Baltimore, Hooker fell into a relatively minor dispute with Army Headquarters and offered his resignation. Lincoln immediately accepted it, replacing him with the waspish but competent Major General George G. Meade on June 28.

"THE PRESIDENT SEEMED TO THINK HIM A LITTLE CRAZY"

So what the devil happened to Hooker at Chancellorsville? Reportedly he had given up whiskey for the campaign; some have suggested that from a psychological standpoint, it was exactly the wrong time to abandon the routine of liquid courage. Others have pointed to the crucial morning of May 3 at Hooker's headquarters, when a Rebel cannonball struck the pillar that he was leaning against, knocking him out for an hour. Suffering a concussion, he nonetheless refused to pass command to General Couch. But I think Hooker's basic problem was one he shared with all men who run primarily on bluster—a propellent that takes them only so far, past which a fundamental insecurity begins to surface and cripple their brains.

Apart from all that, though, we have to wonder: When Hooker asserted the country's need for a dictator, did he envision himself in that role? The authoritarian, the strongman, the "man on horseback?" Rising out of the turmoil to talk straight and point the way? To slash through all the red tape, legal niceties and prissy caveats? To kick ass and take names? To save the country? It's a sort of figure we've come to know on a global scale. Republican government was still relatively new in the American Civil War era—and to many, a dubious proposition. Cold aristocratic eyes gazed from Europe, willing the United States to tear itself apart and disprove its own precepts.

Generally defined, authoritarianism was history's ancient norm, by way of kings, queens and warlords. But a more modern and specific definition was dawning. Napoleon Bonaparte, revered by Northern and Southern military men alike, had already set the template. He was the daring upstart, the bold usurper, the national unifier, the martial genius—France's emperor not by lineage but by his own ambition, as well as the French people's acclaim. He premiered the characteristic central figure of authoritarianism, the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny—or RISOD, as I'll refer to it from here on. To an extent, Fighting Joe fit the self-styled RISOD bill. He had the swagger, the grandiosity, the braggadocio. He was a clever man of action, blazingly free in his belittlement of others.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), Emperor of France, template

for the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny, or RISOD.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But if there was one contemporary who met RISOD specs even more, it was another man whom Hooker had served under and come to despise: George Brinton McClellan, once hailed by Northern newspapers as the "Young Napoleon Of The West." On the heels of the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, 34-year-old Major General McClellan had arrived in Washington in late July, 1861, having scored two minor victories in western Virginia. Born of a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia family, he had graduated second in his class at West Point and served with distinction, even representing the U.S. as an observer in the Crimean War. He then had a creditable run in civilian life, as an official with the Illinois Central and the Ohio & Mississippi Railroads. Except for the malaria he contracted in the Mexican-American War, this was someone who had led a charmed life, without one major personal or professional setback.

The term "narcissist" had not yet been coined, but we may safely view Little Mac through that lens. A high proportion of talented narcissists achieve prominence in public life—and while all of us fall somewhere on the pathology spectrum, this sort of person is essentially different. Still, just an elite few qualify for full-on RISOD status. To call them "arrogant" falls breathtakingly short and is somehow beside the point, like dwelling on how cold it is at the South Pole. Confronted with their stratospheric self-regard, a regular sane person can only smile, maintain eye contact and slowly back out of the room. It is no wonder that presidential secretary John Hay said of Lincoln (a man who'd had plenty of setbacks in life), "The President seemed to think him {McClellan} a little crazy." And who's to say it wasn't a kind of crazy? Often enough, it sure looked that way.

QUAKER GUNS AND CIRCULAR MARCHING

To read McClellan's series of humblebrags to his worshipful wife (and what other kind of wife would a guy like this have?) is to face a choice: do you laugh or puke? But let's get it over with: "God has placed a great work in my hands . . . The people call upon me to save the country—I must save it & cannot respect anything that is in the way . . . I find myself in a new and strange position here—Presdt, Cabinet, Genl Scott & all deferring to me—by some strange operation of magic I seem to have become the power of the land . . . I almost think that were I to win some small success now I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me—but nothing of that kind would please me—therefore I won't be Dictator. Admirable self-denial!" Jesus Christ make him stop.

{For a magnificent cry-from-the-heart concerning the Young Napoleon, I recommend Mallory Ortberg's "Yellin' About McClellan" commentary in The Toast (http://the-toast.net/2014/03/24/i-hat...). And there's Bob Simpson's glorious installment in Crazytown, "McClellan Was An Asshole" (http://www.crazytownblog.com/crazytow...). Both pieces were inspired by their authors' reading Doris Kearns Goodwin's monumental Team Of Rivals: The Political Genius Of Abraham Lincoln.}

Of Little Mac's dispiriting tenure with the Army of the Potomac, here is a thumbnail version: There were his superb organizational skills that worked wonders on the army, whose men generally idolized him—but also, starting early, his wildly inflated estimates of enemy troop strength, while his own army's numbers were in fact much greater. And there was his public disdain for black people and Abolitionists (After the war, he would write, "I confess a prejudice in favor of my own race, & can't learn to like the odor of either Billy goats or niggers"); his friction with the aging general-in-chief, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott—a truly great soldier, whose ouster and title McClellan soon secured; his endless dithering, which let Confederate General Joseph Johnston's army slip away from Manassas and leave behind its "Quaker guns"—logs painted black, fake cannon used to dupe Yankee eyes; his loathing of Lincoln and other federal officials, even as they strove to meet his bottomless demands for men and materiel, and whose entreaties for action sent him on rants ("If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time," said the frustrated Lincoln.)

Major General George B. McClellan—superb organizer,

supreme egotist, poor fighter—with his wife Mary

Ellen Marcy McClellan. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

And there was his spring 1862 offensive up the Peninsula, devolving into a massive snail's creep toward Richmond—while in McClellan's mind, the detective Allan Pinkerton's sloppy intelligence-gathering further magnified the enemy's size, as did some clever Confederate fakery (In Lucifer's Drum, Nathaniel Truly recounts how the Rebs marched in circles to make their Yorktown garrison seem much bigger than it was—and how his boss Pinkerton rejected this report, prompting Truly's cussing resignation); within shouting distance of the Confederate capital—his much faster withdrawal, his nerves unravelling in the Seven Days' Battles; his refusal to reinforce Major General John Pope, one factor in the latter's rout at Second Bull Run; at last, the tragedy of the Maryland Campaign, when he failed to exploit the discovery that Lee's forces were split in four (as revealed in the infamous "Lost Order")—and in the blood-soaked clash at Antietam (September 17, 1862), when he refused to commit his reserves and finish off the outnumbered Lee. On November 5, Lincoln finally sacked him and put in Burnside. In the Presidential race two years later, God called McClellan to "save the country" yet again by running against Lincoln—but Lincoln and the country whomped him, in ungodly fashion.

McCLELLAN'S BODY GUARD

"Self-esteem: an erroneous opinion of oneself."—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary

In the Rugged Individualist Superman Of Destiny, along with the knightly poses and planet-sized self-esteem, with all the God talk and/or Destiny talk, with the flag-draped appeals to "greatness" and "toughness" and "nerve" and "will" (see Triumph Of The), there is a deep well of contempt for others. It is part of what drives him, intensifying as he encounters disagreement and other human obstacles—which, like the authoritarianism he embodies, the RISOD is just not built to tolerate. For him it guarantees chronic rage: how can other people be so stupid, so unpatriotic, such losers? But when things go really bad for him, there is an even deeper well that he draws upon, of self-pity. Self-pity is what Mao Tse Tung reflexively fell into when other Communist Party officials curtailed his power in the early 1960's, after his Great Leap Forward had triggered famine and claimed millions of Chinese lives. (He would later wreak grand-scale RISOD revenge on those officials, when he and his wife launched the ruinous Cultural Revolution.) And self-pity was as much Hitler's refuge as his Berlin bunker in 1945, when he issued the "Nero Decree"—a scorched-earth order to destroy all remaining German industry, transport and supplies—the German people having proven themselves unworthy of him. Reichsminister Albert Speer fortunately disobeyed the order.

But the most central RISOD characteristic, the one that feeds all the others like a vast noxious reservoir, is his relationship with reality. When it comes to truth-telling, the RISOD cuts himself all kinds of slack—because if he is divinely favored, if his cause is by definition just and holy, isn't he right to do or say whatever it takes? Yet at a certain point, it becomes moot whether he is consciously lying or propounding an actual belief, since he sees just what his self-flattering conclusions require him to see. He maintains what amounts to an alternate universe. When it comes to convincing others, the RISOD has the advantage of utterly believing his own propaganda, even if he knows he's fudging the specifics a bit. It's how he's able to conceive himself as a popular hero, conflating his own will with that of The People.

And this talent isn't just an abstract thing. Like a hallucinatory drug, it can edit real-life experience into whatever the RISOD wants. In a letter to his wife, McClellan oozed pity as he recounted the departure of his erstwhile superior and antagonist Winfield Scott: "It was a feeble old man scarce able to walk—hardly any one there to see him off but his successor." But according to the newspapers, a large crowd had gathered at the rail depot to wish Scott a fond farewell, along with both generals' staff members, a cavalry escort and two cabinet secretaries—in a pre-dawn downpour, no less. "Memory is a gentleman," they say—but to McClellan's vanity, it was a slave.

Armed with this pliant view of reality, the RISOD may indulge another of his important traits: blame deflection. (In this area, Napoleon actually seems a cut above the wannabes he spawned, if it's true that he said, "I have been mistaken so often, I no longer blush for it.") McClellan was typical of the breed. Like any general's, his orders implicitly urged personal responsibility on the part of subordinates and government functionaries, who he was quick to blame for whatever went wrong. But God forbid that anyone dare call him to account. When his troops under Brigadier General Charles P. Stone were shattered at Ball's Bluff, the worst decisions of that day (Oct. 21, 1861) were not McClellan's—but he was guilty of poor communication. Still he let the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War scapegoat Stone, who was arrested and imprisoned.

To his wife, McClellan wrote, "The whole thing took place some 40 miles from here without my orders or knowledge. It was entirely unauthorized by me & I am in no manner responsible for it." Had that even been true, an overall commander is supposed to take responsibility for any major action that happens on his watch—but this was the opposite of a stand-up guy. On the Peninsula months later, withdrawing before an enemy half the size that he imagined, McClellan telegraphed Secretary of War Stanton thus: "I have lost this battle because my force was too small. I again repeat that I am not responsible for this . . . If I save this army now, I tell you plainly I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army." I find it hard not to see this capacity for denial as essential cowardice.

Lincoln visiting the Army of the Potomac at Antietam, October 3,

1862, posed with Major General John A. McClernand (right) and

chief detective Allan Pinkerton (left). (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

"Cowardice" is an awfully easy word to throw around, especially for a 21st-Century noncombatant and non-politician. Still, when you look at the RISOD's self-image and public image and then at the recorded facts, the ironies just won't quit. For instance: so much of his sales pitch is about decisiveness—the bracing clarity it brings, the banishment of doubt. It can play well for a time, if enough people are convinced to indulge their black-and-white thinking—some who have reservations might even say, "Well, at least he's decisive. A Leader." But what looks/sounds like decisiveness can end up being mere dismissiveness in disguise—a lazy reflex, and one that bears a striking resemblance to stupidity. It always brings trouble. And as trouble mounts and pressure grows, beneath all the iron certainty, a worm of doubt starts eating away. Doubt, all the more ravenous for its long suppression.

Failure doesn't necessarily follow—the public-image juggernaut can take its owner quite a distance, on sheer momentum. No less a RISOD paragon than Hitler was called (behind his back) a Teppichfresser, a "carpet-eater," owing to his paroxysms of rage when major decisions weighed on him and he could make no call. Journalist and historian William L. Shirer glimpsed Hitler in the midst of the 1938 Munich Crisis and wrote, "he seemed to be on the edge of a nervous breakdown," with physical tics and a look of insomnia. Munich resulted in a great expansionist coup for the Feuhrer, with France and England backing down before his threats. Yet in the war that commenced a year later, at such crucial points as the Normandy Invasion, his high-strung indecisiveness would doom the Nazi cause.

The RISOD cult also has much to do with physical bravery. Its poster boys may in fact show flashes of this in their youth—but as they rise in the world, as the loss of their wondrous selves becomes a harder and harder thought to bear, an obsession with personal safety overtakes them. Threats surely do exist—these are controversial men, after all, who stir up hatred and become targets thereby. If you are someone on the scale of Hitler or Stalin, an enflamed paranoia will even prove sensible—because they definitely are out to get you. But in most cases, the fear is disproportionate—enough to hurt the RISOD's strutting sense of Destiny, as well as his job performance. In his 1922 power-grabbing March On Rome, Benito Mussolini had photos taken of himself marching alongside black-shirted fellow fascists, then high-tailed it back to Milan to see how the confrontation unfolded, far from its danger. Twenty or so years later, when he visited Axis forces in North Africa, German soldiers disdainfully noted his unwillingness to go anywhere near the action.

And McClellan, who shared Il Duce's sense of self-worth? He kept his headquarters far behind the battlefront—on the Peninsula and also at Antietam, so far that it hampered his awareness of events. During the Battle of Malvern Hill (July 1, 1862), McClellan stayed safely aboard a gunboat on the James River while his rear guard repelled the pursuing Rebels. "I must not unnecessarily risk my life," he wrote to his wife, "—for the fate of my army depends on me & they all know it." (For the love of God, Mrs. M., didn't you ever get tired of this??) In his gripping and masterful Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, historian Stephen W. Sears writes of how McClellan hated to lose a single soldier. Compassion—something I'm sure the general was capable of feeling—can be inferred. But as a dominant factor, something else deserves consideration.

It's the nature of the narcissist, the megalomaniac, the RISOD, to see other people as just an extension of himself. Friends, spouses, children—armies. In the Army of the Potomac—that magnificent machine that he had built—how could McClellan not see such a giant self-extension? And how could he not react with horror at its maiming, real or potential? President Lincoln was on to something when, during his visit to the army two weeks after Antietam (and one month before McClellan's dismissal), he gestured toward the legion tents and asked his companion, Illinois Secretary of State Ozias M. Hatch, "Hatch, what is all this?" Hatch replied, "Why, Mr. Lincoln, this is the Army of the Potomac." And Lincoln responded: "No, Hatch, no. This is General McClellan's body-guard."

"LET US BE VIGILANT, BUT KEEP COOL"

In the end, of course, it was neither McClellan nor any other RISOD who vanquished the Confederacy. That achievement, more than any two figures, belonged to Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant—men of modest bearing, grounded and confident but without bravado. Each absorbed the pain of disaster with an unclouded mind. Each seemed uncannily suited to the trial—Lincoln in particular, as has often been said. Under enormous pressure, he had the judgment to resist the tidal pull of authoritarianism, to push the Constitutional envelope without tearing it. With a priceless combination of skill and principle, he was able to launch Emancipation (at some political cost) and then the Thirteenth Amendment, chattel slavery's tombstone. He had the steady temperament for crises. When Jubal Early's Raid (the pivotal historic event for Lucifer's Drum) threatened D.C. and Baltimore, he kept his public words calm and simple: "Let us be vigilant, but keep cool." His multiple strengths made him an ideal vessel for the nation's suffering. In his last photographic portrait, four days before his murder, we behold the majestic ruin of a man—sandblasted by sorrow and strain, yet with his soul entirely there.

In 1888-89, France saw the sudden rise of general and politician Georges Ernest Boulanger. The nation was in turmoil, though nothing that approached what the United States had faced some 25 years earlier, or what France itself had faced after its defeat by Germany in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Boulanger was a populist hero, a bellicose patriot with strong support among monarchists and traditional Catholics, as well as the working class. In his time as War Minister, his advocacy of revenge against Germany earned him the name General Revanche (Revenge) and—no surprise—the backing of Bonapartists. A literal "man on horseback" (his horse was black and picturesque), he cut a dashing figure despite his poor oratory and vague ideas. The song "Boulanger Is The One We Need" whipped up excitement for him and the movement he led—Boulangisme, a patchwork of political elements that reviled the republican government, tilting conservative and authoritarian overall.

The government fought but could not stop his election to the Chamber of Deputies, representing Paris. Immediately after this (January 27, 1889), partisans urged him to lead a coup d'etat and become military dictator. It seemed imminent. But seized by indecision, Boulanger took shelter at the house of his mistress and could not be found. His magic moment having passed, the government brought charges of conspiracy and treason against him—and to the shock of his followers, he fled the country. In September 1891, at a Brussels cemetery, Boulanger stood over the grave of his recently deceased mistress and shot himself in the head.

General Georges Ernest Boulanger (1837-91), would-be

political savior of France. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

I offer Boulanger as a chance to marvel—that in its worst four years, despite everything, the United States experienced no similar close call. I offer him too as an example of boilerplate RISOD. Like McClellan, Boulanger was far from the worst of his kind, in part because he failed. For the worst of them, for the truly successful Rugged Individualist Supermen Of Destiny, we look to the 20th Century: the more focused isms, the more artful disinformation, the midnight purges and secret police, the gulags and extermination camps and wars of conquest. But in history's rearview mirror, viewed simply as men, they all look less like messiahs and more like preening blowhards—loud but small, clownish, strangely weak.

Americans should avoid self-congratulation on never having had such a figure in highest office—because there have been some pretty ruthless occupants, regardless. Besides, it could just be more of our relative good fortune—that the right events haven't yet collided within the right state of decay. Because whenever people pour into ideological cul de sacs, when they care less about facts than about how they feel, when demagoguery goes mainstream, and when what Joan Didion called "the thin whine of hysteria" is constant, the RISOD peril looms large. Yuge, in fact.

Published on July 19, 2016 18:06

•

Tags:

abraham-lincoln, authoritarianism, battle-of-chancellorsville, bernie-mackinnon, general-george-mcclellan, general-joseph-hooker, horatio-seymour, lucifer-s-drum, risod

No comments have been added yet.