Thank yew for reading

Margaret Evans Porter communing with the yews

The yew tree appears in my Arnaud Legacy series with great import, so when I recently saw something on Facebook from fellow author Margaret Evans Porter about yew trees, I asked her if she’d be willing to guest post here. She very graciously said yes, and included a plethora of gorgeous photographs.

This is going to be a pleasure…pour a cup of tea and enjoy learning more about these trees with a fascinating history! Thank you so much for posting today, Margaret!

Designing a garden is an expression of my creativity that involves my love of history, beauty, fragrance, and personal connections. I grow from cuttings given to me by my rose-growing mother, and I’ve got the offspring of boxwood and yew from many generations beyond me. I grow roses that my characters know and grow (especially my late 18th century garden designer heroine.) Many of these varieties are centuries old, and I value their history as much as their hardiness and reliability.

Rosa Mundi has been known since the 16th century

In addition to roses (about 90 plants at last count), I grow culinary and medicinal herbs, and many old-fashioned perennials like foxglove, delphinium, yarrow, and cranesbill. Quite a few of my most treasured plants are ones that I successfully moved to my previous home to my current one. When in England or other countries, a favourite activity is visiting historic gardens.

I’m quite familiar with the lore associated with yews, partly from general study of English, Scots, Irish, Welsh, and Manx folklore but specifically because of family lore and in connection with book research. In the Celtic tradition, yew is sacred. Because I often write about those cultures and have Celtic heritage, I can’t remember when I didn’t know about the various properties of the yew tree!

Yew in a Buckinghamshire graveyard

It is regarded as one of the most long-lived trees, and some are believed to have existed for a thousand years or more. Its supposed connection to eternal life explains its attractiveness as a Christian symbol, and why the yew is so often found in graveyards and growing beside churches. But even in ancient times it had associations with life and death.

The leaves and barks are poisonous if eaten. Yet in modern times, its health benefits have been recognised. Taxol and similar drugs used in treating certain cancers, are derived from yew. Though it is made synthetically, yew leaves continue to be a component in its manufacture.

Old yew tree in an ancestral churchyard in Gloucestershire

I visit many ancestral churchyards where yew trees have grown for centuries, and have a habit of taking cuttings from these venerable trees which might have been known to my forbears. They develop into miniature trees, which I keep as houseplants.

A piece of a large tree is now a tiny tree

Last year I added this yew shrub to my garden, it’s so nice having evergreens—especially in wintertime. I haven’t decided whether to keep it neatly trimmed or let it grow as it pleases.

The yew in my garden

As mentioned earlier, because I so often visit historic gardens in Britain, I’m accustomed to seeing clipped yew tree topiaries and hedges as landscape features. Some of my favourite yews are the ones at Hampton Court Palace, planted there by 18th century garden designer Capability Brown. Nowadays they have a sort of umbrella or toadstool shape. Also at Hampton Court is the famous maze—I’ve been getting confused there ever since I was a teenager, but I do love it. When it was laid out around 1700, it was planted with hornbeam, but at a later date it was re-planted with yew.

The yews at Hampton Court

One of my favourite possessions is a pen made of yew wood, which my mother purchased for me in the Costwolds many years ago. It’s always on my desk, I use it every day.

My yew wood pen

Yew trees definitely turn up within my novels. The heroine of The Proposal, the lady landscape designer and rosarian, appreciates the formal gardening styles and in reviving a neglected garden hopes to restore shaved hedges and topiaries. When the heroine of The Seducer begins to learn archery, her husband commissions for her a bow made of yew wood.

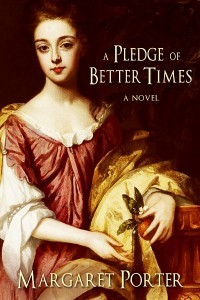

My gardening life and my writing life are so closely entwined. In writing A Pledge of Better Times, I depicted the development of Hampton Court’s formal gardens by Queen Mary II, and explore the symbolism of oranges—my real-life heroine, featured on the novel’s cover, is holding one. Was there a particular reason for it?

My thanks to Lynn for inviting me to share my appreciation of special plants and gardens, topics very important to me in so many ways!

Many thanks to you, Margaret. I’m in awe of your gardening and your wonderful array of novels. It’s a great honor to have you here today.

MARGARET PORTER is the author of A Pledge of Better Times and eleven more British-set historical novels for various publishers, including bestsellers, award-winners, and foreign language editions. She studied British history in the U.K. and afterwards worked in theatre, film and television. Margaret returns annually to Great Britain to research her books. She and her husband live in New England with their two dogs, dividing their time between a book-filled house in a small city and a waterfront cottage located on one of the region’s largest lakes. She tweets as @MargaretAuthor. More information is available at her website, www.margaretporter.com.

And because we can’t resist: a few more photographs of her incredible roses:

I’ve always grown this highly scented damask rose, used by the perfume trade

Climbing roses

All photographs and captions are used courtesy of Margaret Evans Porter. Thank yew!

. . . .