From Lucifer's Drum: Remembering The Bloodiest Day In U.S. History

In its July 1864 raid into Maryland and eventually against Washington, D.C., Confederate General Jubal A. Early's 14,000-man force paused near Sharpsburg, site of American history's bloodiest one-day battle less than two years earlier. A technical victory for the North, the Battle of Antietam (a.k.a. Sharpsburg) is remembered just as much for Union commander George B. McClellan's squandered opportunities—his failure to exploit the discovery (via the infamous "Lost Order") that Robert E. Lee had split his army in four, and to commit more than a quarter of his available troops in the titanic clash itself. About 4,000 men were killed and nearly 19,000 left wounded, captured or missing. My future wife and I once visited the battlefield. In the late-summer stillness and the brassy luster of late afternoon, it did feel haunted.

On the Union side of my novel Lucifer's Drum, two central characters—federal agents Major Nathaniel Truly and Captain Bartholomew Forbes—remain haunted by Antietam. Truly, an army scout at the time, privately recalls—"Miles to the rear, atop a ridge, he had listened as man-made thunder engulfed the sky. With McClellan’s army smashing into Lee’s, he had imagined a huge black portal on the horizon and soldiers pouring through, rank upon rank. Spilling into the void. At first it had felt like a monotonous dream, nothing more. Then came the sensation—that picking at his spine, something like the dread of battle and yet worse. A dread devoid of hope. Safe behind the lines, he felt not only small but coldly, utterly separate. The guns were God, pummeling him to vapor. They roared extinction."

Forbes is less fortunate, having lost a leg in a skirmish on the great battle's eve. Late in the book, while suffering phantom pains, he recounts it—"The day before, my regiment was with Hooker’s corps on the right. We crossed the creek near Keedysville and blundered into enemy pickets. Their artillery kicked up. The next thing I knew, I’d joined the Brotherhood of the Stump . . . I was taken to a barn set up as a field hospital. That first night, there were just a few other wounded. I was under morphine but the guns still woke me at dawn. By mid-morning the barn was full and they moved me outside. By noon the surrounding acre was covered with wounded and by mid-afternoon they covered the surrounding five. There were pyramids of amputated limbs outside the barn. Twice, the roar of the fighting died down and then erupted farther south. Come evening, it all turned quiet except for the wails and moaning. I was evacuated to Frederick, and that’s where I heard my company had been decimated, my regiment half destroyed.”

On that day—September 17, 1862—the nation crossed and burned a symbolic bridge, ensuring that the war would grind on and yield many more mounds of dead. We can scarcely guess what the reflections of veterans like Early were, finding themselves returned to those former scenes of hell. But in this chapter from my novel, I made the attempt:

HERE, WHERE ARTILLERY had ripped the earth and sky, where barns and haystacks had burned, where battle lines had surged, withered and disintegrated, trailing bodies through the bullet-lashed corn and along the wooden fences—here, where slaughter had reigned, all was peaceful. The day was warm and clear, the corn high and the barns rebuilt. To the west, a Confederate encampment ringed the fair Unionist town of Sharpsburg, its citizens pondering their fate before another invasion. To the east, between steep wooded banks, Antietam Creek looped its way to the Potomac. Early’s musings today were unusual, and he wished that the others had not wandered off so soon. He wanted to ask aloud if human struggle ever amounted to much. Once the smoke cleared and the last cry faded, what really remained except headstones and fever dreams?

He raised his field glasses. Across the undulating green of the landscape, by the Hagerstown Pike, he spied the tiny white church with no steeple. The church had marked the battle’s axis. From behind it, through those same trees, Early had led his brigade to “relieve” Hood’s division, though the latter was mincemeat by then. He recalled the gun roar, drowning the Rebel yell and the Yankee war-whoop; men charging, heads bowed to the tempest, falling like locusts in a fire. September 17th, 1862—nothing before or since had matched it. Not Gettysburg, not the Wilderness or Spotsylvania.

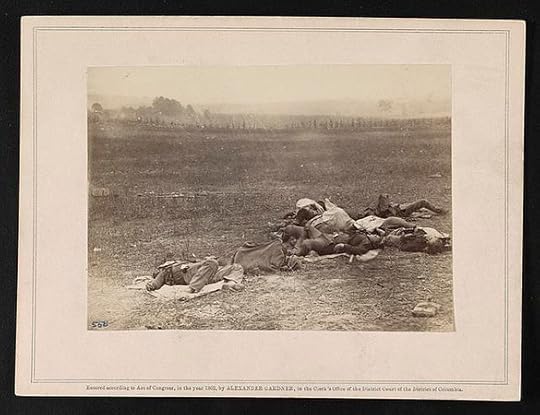

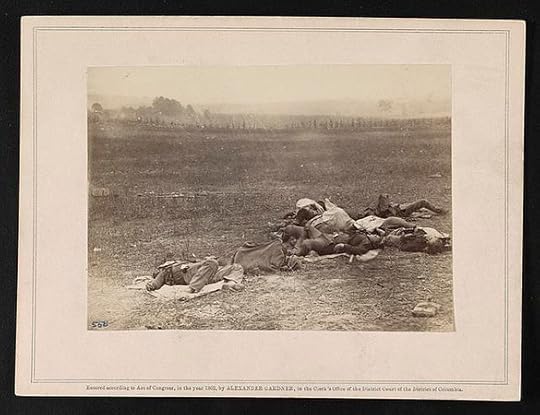

Famous image by Alexander Gardner, showing dead Confederate artillerymen by Dunker Church, near Robert E. Lee's center at Antietam. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

On a stone bridge over the creek, two boys sat with fishing poles, feet dangling. Scanning along the Boonsboro Pike, Early picked out the solitary figure of Gordon, dismounted now, lost in thoughts of his own. Early lowered the binoculars. Against all his usual feelings toward Gordon, a sense of brotherly connection took hold. On that endless roaring day, the Georgian had defended a stretch of sunken road known thereafter as Bloody Lane. Through one Northern assault after another, the position held fast until Gordon was carried from the field, five times wounded. His men fought on, only to die in rows and mounds amid a final onslaught. Yet their stand had exhausted the enemy and unsettled McClellan, who then failed to exploit the breach.

Early dismounted to stretch his legs. Doing so, he saw Kyd Douglas riding slowly toward him up the gentle slope.

Halting by Early’s horse, the major gave an absent smile and hopped down. “I was just remembering, Genr’l—late that day I found Jackson eating a peach, sitting there with his dead all ‘round him. You know what he said?”

“‘God has been good to us,’” Early quoted. “I heard it from someone.”

“Well, I was thinking too—for all that, God was good to us. Wasn’t He?”

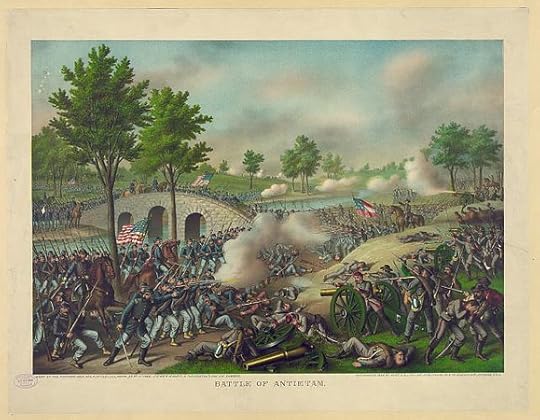

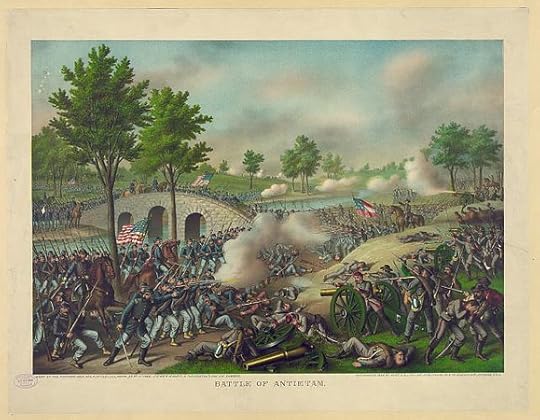

This 1887 print shows the Union assault around Dunker Church. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Shy of this Almighty reference, Early looked away. He ran a hand through his beard. “Suppose so, if it was Him working on McClellan. I didn’t truly see it till it was all over, but McClellan could have finished us here. If he’d thrown his reserves in . . . ”

“Or even if he’d renewed the attack next morning,” said Douglas. “But no, he just sat there and let us limp back across the river.”

“Yes, well . . . There’s no substitute for nerve.”

God was as good an explanation as any. It had been good enough for Jackson.

Rubbing his sore hips, Early assumed a hearty air. “Your father was right hospitable. In your next letter to him, pass along my respects.”

Douglas gave an appreciative nod. Though brief, their visit to the nearby home of his widowed father had been pleasant. “He was honored to have you. Since the day I joined up for the South, he’s taken a heap of abuse from Yankee neighbors.”

“It must be an extra trial, coming from a border state,” said Early.

The major’s eyes turned distant. “I was speaking of that with General Breckinridge. It’s worse for him. Seems he’s related to half of Kentucky, folks on both sides of the war. Including Mary Lincoln, did you know? ‘Cousin Mary,’ he calls her.”

Early grunted. “Do tell! Well, we might be calling on Cousin Mary pretty soon. And her husband.”

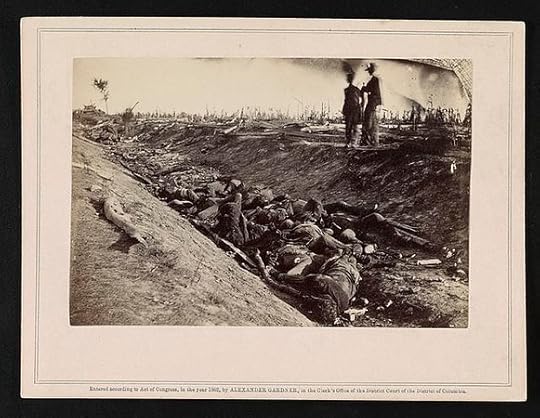

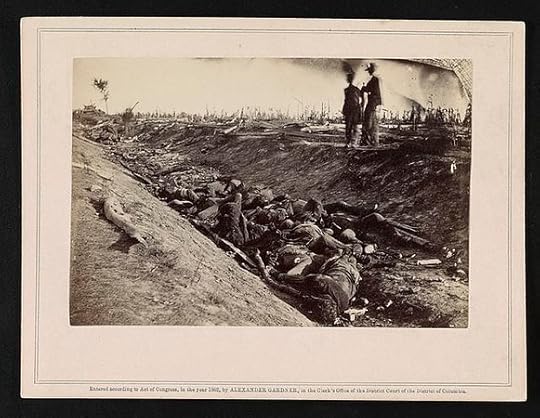

Another Alexander Gardner image, showing dead of the federal Irish Brigade. Taking

60 per cent casualties, the brigade had assaulted the sunken road known as "Bloody

Lane," in the Confederate center. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Douglas removed his hat and wiped his brow, then pointed. “There he is now.”

In the distance, Early picked out the mounted, majestic figure of Breckinridge in his dark blue coat, trotting along the road toward Gordon. Gordon remounted as Breckinridge drew up, and the two began speaking. Early sighed wearily. Logistical matters had begun to crowd his head once more. First, though, there was an issue that he could postpone no longer. “I need a word with him, Douglas. You’d best be getting back to Ramseur’s camp.”

The major departed. Early mounted up and descended into the rolling terrain, losing sight of the two generals. When the pike reappeared, there was only Breckinridge riding toward town. Early veered to intercept him. Seeing him, the Kentuckian reined up.

“Gordon was asking about the shoes again,” said Breckinridge.

Early drew alongside. “They should arrive tomorrow.”

“Good. Back at the ford, it was hell for the barefoot ones–all those sharp rocks.”

Early was tired of the shoe predicament. “They’re going without a lot of things. Forage and supplies are scarce, but we’re doing our best. It’s more vital than ever to maintain order.” From Breckinridge’s pained look, it was clear he had guessed where this was leading. Early continued briskly. “It hardly needs saying: we can’t permit a repeat of Martinsburg.”

Breckinridge gave a stoic nod. “No. We cannot.”

Print from 1887 shows Union troops storming the stone bridge—"Burnside's Bridge"

—on the Confederate right. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“Your men’s gladness was understandable. Marching up to the depot and seeing all those Fourth-of-July victuals the enemy left–it must have seemed like paradise.”

“After days of eating parched corn, yes. Still . . . ”

The enemy retreat had been too swift. From Martinsburg, from Harper’s Ferry, across the river to the safety of Maryland Heights—all before a major attack could be pressed. Yankee skittishness had foiled rather than aided Early’s trap. Yet it had proven a boon for Breckinridge’s corps at Martinsburg, where rail cars and warehouses groaned with abandoned delicacies. The resultant orgy of eating, drinking and plunder did not bode well for discipline.

“I’m issuing a general order,” Early said. “Any more marauding and such will be summarily punished.”

“I’ll see that it’s enforced,” said Breckinridge.

The discomfort passed. Once more Early was glad to have Breckinridge at his side. Whatever the glittering titles of his past, he could still listen manfully to criticism.

Early pulled the stopper from his canteen. “That’s not to say we can’t exact retribution. I’ve sent McCausland up to Hagerstown . . . ” He took a swig and offered the canteen to Breckinridge, who took it. “It’s a fair-sized place. He has orders to return with two-hundred thousand dollars, cash or gold or both. If the citizens don’t raise it, the town burns.” As Breckinridge gave back the canteen, Early checked for signs of chivalric disapproval. There was a slight aversion of the eyes, nothing more. “Our primary goal remains one of diversion,” Early said. “Washington has sent no fresh troops our way, so we can conclude that they underestimate our size. But now we want to frighten the bejesus out of them. Our cavalry’s ranging as wide as possible, along with the partisans of Mosby and Gilmoor, striking in small groups wherever they can. In Yankee minds, we’ll go from a minor raiding party to twice our actual strength.”

A ditch full of Confederate dead after the Battle of Antietam. (Courtesy: Library of

Congress)

Breckinridge smirked. “Not that we don’t pose a real threat as we are.”

“Yep–quite a raiding party. And at this moment, we represent the northernmost reach of the Confederacy.” He squinted down the pike, then across a wheat field to the creek. Through its curtain of trees, the creek sparkled. “I tell you, we had the devil’s own day here.”

“So I’m told,” said Breckinridge.

Early fiddled with the reins. Against the sky, a long chain of crows straggled eastward. “The way the ground is, you couldn’t see it all from a given spot. You could damn well hear it, though. At dusk we were collecting our casualties and I looked out on the field—up there around the church. It was squirming. I knew it was wounded men out there, dying men, but the whole field was like some crawling, moaning thing. Just acres of . . . "He glanced at Breckinridge. Previously assigned to the western theater, Breckinridge had not been here two years ago but had, no doubt, seen his share of crawling fields. These somber reflections should end now, Early decided. “Is Gordon set to make his demonstration against the Heights?”

“He’s moving within the hour,” said Breckinridge.

Against all of Early’s fighting instincts, he would order no assault against the dug-in foe. Time and speed were paramount. “While Gordon executes his feint, the cavalry will probe the mountain passes north of here. Then we’ll push the whole force through, toward Frederick. We’ll be gone before they know it.”

“Frederick . . . ,” Breckinridge murmured. “Pretty close to Washington.”

“Forty miles or so,” said Early. Further instructions from Lee would soon arrive, as would further word about the traitorous Yankee officer. In a high-flown mood, Early lifted his gaze to the blue distance. The crows were bobbing black flecks. “Not far at all,” he said.

On the Union side of my novel Lucifer's Drum, two central characters—federal agents Major Nathaniel Truly and Captain Bartholomew Forbes—remain haunted by Antietam. Truly, an army scout at the time, privately recalls—"Miles to the rear, atop a ridge, he had listened as man-made thunder engulfed the sky. With McClellan’s army smashing into Lee’s, he had imagined a huge black portal on the horizon and soldiers pouring through, rank upon rank. Spilling into the void. At first it had felt like a monotonous dream, nothing more. Then came the sensation—that picking at his spine, something like the dread of battle and yet worse. A dread devoid of hope. Safe behind the lines, he felt not only small but coldly, utterly separate. The guns were God, pummeling him to vapor. They roared extinction."

Forbes is less fortunate, having lost a leg in a skirmish on the great battle's eve. Late in the book, while suffering phantom pains, he recounts it—"The day before, my regiment was with Hooker’s corps on the right. We crossed the creek near Keedysville and blundered into enemy pickets. Their artillery kicked up. The next thing I knew, I’d joined the Brotherhood of the Stump . . . I was taken to a barn set up as a field hospital. That first night, there were just a few other wounded. I was under morphine but the guns still woke me at dawn. By mid-morning the barn was full and they moved me outside. By noon the surrounding acre was covered with wounded and by mid-afternoon they covered the surrounding five. There were pyramids of amputated limbs outside the barn. Twice, the roar of the fighting died down and then erupted farther south. Come evening, it all turned quiet except for the wails and moaning. I was evacuated to Frederick, and that’s where I heard my company had been decimated, my regiment half destroyed.”

On that day—September 17, 1862—the nation crossed and burned a symbolic bridge, ensuring that the war would grind on and yield many more mounds of dead. We can scarcely guess what the reflections of veterans like Early were, finding themselves returned to those former scenes of hell. But in this chapter from my novel, I made the attempt:

HERE, WHERE ARTILLERY had ripped the earth and sky, where barns and haystacks had burned, where battle lines had surged, withered and disintegrated, trailing bodies through the bullet-lashed corn and along the wooden fences—here, where slaughter had reigned, all was peaceful. The day was warm and clear, the corn high and the barns rebuilt. To the west, a Confederate encampment ringed the fair Unionist town of Sharpsburg, its citizens pondering their fate before another invasion. To the east, between steep wooded banks, Antietam Creek looped its way to the Potomac. Early’s musings today were unusual, and he wished that the others had not wandered off so soon. He wanted to ask aloud if human struggle ever amounted to much. Once the smoke cleared and the last cry faded, what really remained except headstones and fever dreams?

He raised his field glasses. Across the undulating green of the landscape, by the Hagerstown Pike, he spied the tiny white church with no steeple. The church had marked the battle’s axis. From behind it, through those same trees, Early had led his brigade to “relieve” Hood’s division, though the latter was mincemeat by then. He recalled the gun roar, drowning the Rebel yell and the Yankee war-whoop; men charging, heads bowed to the tempest, falling like locusts in a fire. September 17th, 1862—nothing before or since had matched it. Not Gettysburg, not the Wilderness or Spotsylvania.

Famous image by Alexander Gardner, showing dead Confederate artillerymen by Dunker Church, near Robert E. Lee's center at Antietam. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

On a stone bridge over the creek, two boys sat with fishing poles, feet dangling. Scanning along the Boonsboro Pike, Early picked out the solitary figure of Gordon, dismounted now, lost in thoughts of his own. Early lowered the binoculars. Against all his usual feelings toward Gordon, a sense of brotherly connection took hold. On that endless roaring day, the Georgian had defended a stretch of sunken road known thereafter as Bloody Lane. Through one Northern assault after another, the position held fast until Gordon was carried from the field, five times wounded. His men fought on, only to die in rows and mounds amid a final onslaught. Yet their stand had exhausted the enemy and unsettled McClellan, who then failed to exploit the breach.

Early dismounted to stretch his legs. Doing so, he saw Kyd Douglas riding slowly toward him up the gentle slope.

Halting by Early’s horse, the major gave an absent smile and hopped down. “I was just remembering, Genr’l—late that day I found Jackson eating a peach, sitting there with his dead all ‘round him. You know what he said?”

“‘God has been good to us,’” Early quoted. “I heard it from someone.”

“Well, I was thinking too—for all that, God was good to us. Wasn’t He?”

This 1887 print shows the Union assault around Dunker Church. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Shy of this Almighty reference, Early looked away. He ran a hand through his beard. “Suppose so, if it was Him working on McClellan. I didn’t truly see it till it was all over, but McClellan could have finished us here. If he’d thrown his reserves in . . . ”

“Or even if he’d renewed the attack next morning,” said Douglas. “But no, he just sat there and let us limp back across the river.”

“Yes, well . . . There’s no substitute for nerve.”

God was as good an explanation as any. It had been good enough for Jackson.

Rubbing his sore hips, Early assumed a hearty air. “Your father was right hospitable. In your next letter to him, pass along my respects.”

Douglas gave an appreciative nod. Though brief, their visit to the nearby home of his widowed father had been pleasant. “He was honored to have you. Since the day I joined up for the South, he’s taken a heap of abuse from Yankee neighbors.”

“It must be an extra trial, coming from a border state,” said Early.

The major’s eyes turned distant. “I was speaking of that with General Breckinridge. It’s worse for him. Seems he’s related to half of Kentucky, folks on both sides of the war. Including Mary Lincoln, did you know? ‘Cousin Mary,’ he calls her.”

Early grunted. “Do tell! Well, we might be calling on Cousin Mary pretty soon. And her husband.”

Another Alexander Gardner image, showing dead of the federal Irish Brigade. Taking

60 per cent casualties, the brigade had assaulted the sunken road known as "Bloody

Lane," in the Confederate center. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Douglas removed his hat and wiped his brow, then pointed. “There he is now.”

In the distance, Early picked out the mounted, majestic figure of Breckinridge in his dark blue coat, trotting along the road toward Gordon. Gordon remounted as Breckinridge drew up, and the two began speaking. Early sighed wearily. Logistical matters had begun to crowd his head once more. First, though, there was an issue that he could postpone no longer. “I need a word with him, Douglas. You’d best be getting back to Ramseur’s camp.”

The major departed. Early mounted up and descended into the rolling terrain, losing sight of the two generals. When the pike reappeared, there was only Breckinridge riding toward town. Early veered to intercept him. Seeing him, the Kentuckian reined up.

“Gordon was asking about the shoes again,” said Breckinridge.

Early drew alongside. “They should arrive tomorrow.”

“Good. Back at the ford, it was hell for the barefoot ones–all those sharp rocks.”

Early was tired of the shoe predicament. “They’re going without a lot of things. Forage and supplies are scarce, but we’re doing our best. It’s more vital than ever to maintain order.” From Breckinridge’s pained look, it was clear he had guessed where this was leading. Early continued briskly. “It hardly needs saying: we can’t permit a repeat of Martinsburg.”

Breckinridge gave a stoic nod. “No. We cannot.”

Print from 1887 shows Union troops storming the stone bridge—"Burnside's Bridge"

—on the Confederate right. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“Your men’s gladness was understandable. Marching up to the depot and seeing all those Fourth-of-July victuals the enemy left–it must have seemed like paradise.”

“After days of eating parched corn, yes. Still . . . ”

The enemy retreat had been too swift. From Martinsburg, from Harper’s Ferry, across the river to the safety of Maryland Heights—all before a major attack could be pressed. Yankee skittishness had foiled rather than aided Early’s trap. Yet it had proven a boon for Breckinridge’s corps at Martinsburg, where rail cars and warehouses groaned with abandoned delicacies. The resultant orgy of eating, drinking and plunder did not bode well for discipline.

“I’m issuing a general order,” Early said. “Any more marauding and such will be summarily punished.”

“I’ll see that it’s enforced,” said Breckinridge.

The discomfort passed. Once more Early was glad to have Breckinridge at his side. Whatever the glittering titles of his past, he could still listen manfully to criticism.

Early pulled the stopper from his canteen. “That’s not to say we can’t exact retribution. I’ve sent McCausland up to Hagerstown . . . ” He took a swig and offered the canteen to Breckinridge, who took it. “It’s a fair-sized place. He has orders to return with two-hundred thousand dollars, cash or gold or both. If the citizens don’t raise it, the town burns.” As Breckinridge gave back the canteen, Early checked for signs of chivalric disapproval. There was a slight aversion of the eyes, nothing more. “Our primary goal remains one of diversion,” Early said. “Washington has sent no fresh troops our way, so we can conclude that they underestimate our size. But now we want to frighten the bejesus out of them. Our cavalry’s ranging as wide as possible, along with the partisans of Mosby and Gilmoor, striking in small groups wherever they can. In Yankee minds, we’ll go from a minor raiding party to twice our actual strength.”

A ditch full of Confederate dead after the Battle of Antietam. (Courtesy: Library of

Congress)

Breckinridge smirked. “Not that we don’t pose a real threat as we are.”

“Yep–quite a raiding party. And at this moment, we represent the northernmost reach of the Confederacy.” He squinted down the pike, then across a wheat field to the creek. Through its curtain of trees, the creek sparkled. “I tell you, we had the devil’s own day here.”

“So I’m told,” said Breckinridge.

Early fiddled with the reins. Against the sky, a long chain of crows straggled eastward. “The way the ground is, you couldn’t see it all from a given spot. You could damn well hear it, though. At dusk we were collecting our casualties and I looked out on the field—up there around the church. It was squirming. I knew it was wounded men out there, dying men, but the whole field was like some crawling, moaning thing. Just acres of . . . "He glanced at Breckinridge. Previously assigned to the western theater, Breckinridge had not been here two years ago but had, no doubt, seen his share of crawling fields. These somber reflections should end now, Early decided. “Is Gordon set to make his demonstration against the Heights?”

“He’s moving within the hour,” said Breckinridge.

Against all of Early’s fighting instincts, he would order no assault against the dug-in foe. Time and speed were paramount. “While Gordon executes his feint, the cavalry will probe the mountain passes north of here. Then we’ll push the whole force through, toward Frederick. We’ll be gone before they know it.”

“Frederick . . . ,” Breckinridge murmured. “Pretty close to Washington.”

“Forty miles or so,” said Early. Further instructions from Lee would soon arrive, as would further word about the traitorous Yankee officer. In a high-flown mood, Early lifted his gaze to the blue distance. The crows were bobbing black flecks. “Not far at all,” he said.

Published on September 17, 2017 14:14

•

Tags:

battle-of-antietam, bernie-mackinnon, george-b-mcclellan, henry-kyd-douglas, john-b-gordon, john-c-breckinridge, jubal-a-early, lucifer-s-drum

No comments have been added yet.