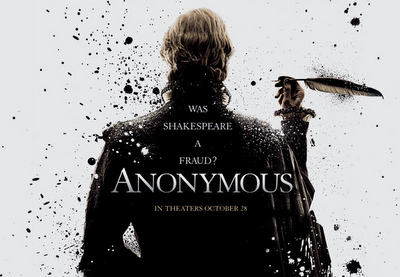

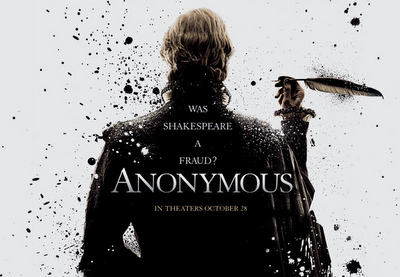

ANONYMOUS: See it twice

So now we come to ANONYMOUS, with perhaps a better idea of where it fits in the Shakespeare authorship controversy.

I liked this movie a lot. It's a beautiful and splendidly acted film, and considerably more intelligent than it is likely to be given credit for.

How much does it prove about the authorship? It proves nothing. It's fiction; it wants to tell a story, and it tells a ripping good one.

Roland Emmerich knows how to create spectacle and outdoes himself here. Every single frame has something for fans of the Elizabethan period. The tenniscourt! The bear baiting! The Globe! Theburning of the Globe! London! If you liked Titanic or Shakespearein Love, you're going to thrill at what Emmerich has done.

But it's no more factual than Shakespeare in Love, and doesn't mean to be.

One of the most beautiful shots in the film, heart-stoppingly lovely, is the panorama of Queen Elizabeth's funeral on a frozen Thames, thousands of people all in black following an enormous black-draped carriage. It perfectly captures the stunned bereavement of a nation, the jagged white void at the center of Shakespeare's London.

And it's a complete fabrication. Queen Elizabeth's funeral was inApril. ANONYMOUS is factually,egregiously dead wrong, consciously dead wrong, dog-rolling-in-awful-stuff wrong, in ways that a mere child canspot. And that's OK. The action of the story starts around 1599, but Kit Marlowe is still alive, wellpast his sell-by date. (Zombie Marlowe? If only.) He iskilled in a mugging in London, not in a tavern in Deptford. Anne Cecil lives to draw the sheetover Oxford's dead face, embodying the Cecils' scorn of him. Robert Cecil is already alive to be jealous of the golden Oxford boy arriving inthe Cecil house.

In other words, this isn't history.

Surprise. It's a movie.

[image error]

Even if you think Oxford wrote Shakespeare's works, it isn't history. It's Amadeus. Think an emotion-frozen Mozart with an unexpected Salieri--a Mozart who has not only been told, but believes, that the one thing he wants to do is the thing that will most disgrace him. This is a history of emotions, a life "as 'twere". Draw the line between truth and fiction wherever you want to: The Living Dead, Queen Elizabeth's bastards, Edward de Vere as Shakespeare.

But the characters ring true.

As far as Emmerich's concerned, get over it, Edward de Vere wrote the plays. Rhys Ifans plays deVere as a real piece of work, held-back, snobbish, caught in his social place. "Plays are not written by people likeme. They are written by people likeyou," he tells Ben Jonson, and follows it up with remarking dismissively that he chose Jonson as a front man because "You have no voice." He is a man who believes that he will ruin himself by being himself, and in the snake pit of London, he's probably right. He allows only two things to touch him, a son he cannot claimand works he cannot put his name to. Ifans shows a whole new side of his acting, revealing Oxford charily, in momentary distrustful flickers. Oxford, at the theater, realizes that here is raw political power waiting to be grasped; he leans forward for a single moment before catching himself. Having rescued Henryfrom death, he allows himself to embrace him once. His fingers are always inky, but only once do we actually see him writing:stripped of his caution, listening.Who knew Emmerich could direct actors so well? The unexpected central character is BenJonson, the stand-in for our democratic indignation. A poet to his bones, Jonson knows absolutely that the elitist deVere is only playing. Sebastian Armesto, as Jonson, movesfrom disdain to stricken dismay to narrow-eyed professional jealousy, and finally to anunexpectedly moving encounter with a fellow poet. Edward Hogg plays Robert Cecil like the smartest snake in the pit, a Puritan Richard III. Mark Rylance, billed as Condell, combines all the immortal actors who spoke Shakespeare's lines, an embodied play-spirit madeflesh. Sir Derek Jacobi, a fussy hurriedPrologue with an umbrella, rises into greatness on his own voice.

It would be a spoiler to talk about all the things the characters accuse each other of (and look who does the accusing). The central story is the succession--who will reign after Elizabeth?--and children and parenthood are as central to this movie as poetry. Who is the father of a child, who is the father of Shakespeare's poetry, and who can lay claim to their children? The great child is England, acted by the eager faces of the people of London, a reluctantly enchanted handful of poets, the tragically young conspirators Essex and Southampton, a delusional queen.

A story that flips around over half a century takes a lot of setting up, and the first few minutes are as confusing as a Shakespeare play. Fitting characters into this Procrustean plot, Emmerich happily gives some less than their due. Queen Elizabeth is raddled rather than regal and Sir William Cecil is a one-note Puritan.

And what about Shakespeare? Rafe Spall of Shaun of the Dead does a neat turn as cocksure, clueless W.S. of Stratford. His Shakespeare knows he's born to be the hero—writer John Orloff gives him a wonderful early scene, "I'm an actor. I crave to act"—but the real joke is his striking physical resemblance to W.S. How can the spitting image of the Bard be such a con man?

It's a big, overstuffed, sometimes untidy movie, and you may be infuriated by it. But you'll want to see it.

I want to see it twice.

I liked this movie a lot. It's a beautiful and splendidly acted film, and considerably more intelligent than it is likely to be given credit for.

How much does it prove about the authorship? It proves nothing. It's fiction; it wants to tell a story, and it tells a ripping good one.

Roland Emmerich knows how to create spectacle and outdoes himself here. Every single frame has something for fans of the Elizabethan period. The tenniscourt! The bear baiting! The Globe! Theburning of the Globe! London! If you liked Titanic or Shakespearein Love, you're going to thrill at what Emmerich has done.

But it's no more factual than Shakespeare in Love, and doesn't mean to be.

One of the most beautiful shots in the film, heart-stoppingly lovely, is the panorama of Queen Elizabeth's funeral on a frozen Thames, thousands of people all in black following an enormous black-draped carriage. It perfectly captures the stunned bereavement of a nation, the jagged white void at the center of Shakespeare's London.

And it's a complete fabrication. Queen Elizabeth's funeral was inApril. ANONYMOUS is factually,egregiously dead wrong, consciously dead wrong, dog-rolling-in-awful-stuff wrong, in ways that a mere child canspot. And that's OK. The action of the story starts around 1599, but Kit Marlowe is still alive, wellpast his sell-by date. (Zombie Marlowe? If only.) He iskilled in a mugging in London, not in a tavern in Deptford. Anne Cecil lives to draw the sheetover Oxford's dead face, embodying the Cecils' scorn of him. Robert Cecil is already alive to be jealous of the golden Oxford boy arriving inthe Cecil house.

In other words, this isn't history.

Surprise. It's a movie.

[image error]

Even if you think Oxford wrote Shakespeare's works, it isn't history. It's Amadeus. Think an emotion-frozen Mozart with an unexpected Salieri--a Mozart who has not only been told, but believes, that the one thing he wants to do is the thing that will most disgrace him. This is a history of emotions, a life "as 'twere". Draw the line between truth and fiction wherever you want to: The Living Dead, Queen Elizabeth's bastards, Edward de Vere as Shakespeare.

But the characters ring true.

As far as Emmerich's concerned, get over it, Edward de Vere wrote the plays. Rhys Ifans plays deVere as a real piece of work, held-back, snobbish, caught in his social place. "Plays are not written by people likeme. They are written by people likeyou," he tells Ben Jonson, and follows it up with remarking dismissively that he chose Jonson as a front man because "You have no voice." He is a man who believes that he will ruin himself by being himself, and in the snake pit of London, he's probably right. He allows only two things to touch him, a son he cannot claimand works he cannot put his name to. Ifans shows a whole new side of his acting, revealing Oxford charily, in momentary distrustful flickers. Oxford, at the theater, realizes that here is raw political power waiting to be grasped; he leans forward for a single moment before catching himself. Having rescued Henryfrom death, he allows himself to embrace him once. His fingers are always inky, but only once do we actually see him writing:stripped of his caution, listening.Who knew Emmerich could direct actors so well? The unexpected central character is BenJonson, the stand-in for our democratic indignation. A poet to his bones, Jonson knows absolutely that the elitist deVere is only playing. Sebastian Armesto, as Jonson, movesfrom disdain to stricken dismay to narrow-eyed professional jealousy, and finally to anunexpectedly moving encounter with a fellow poet. Edward Hogg plays Robert Cecil like the smartest snake in the pit, a Puritan Richard III. Mark Rylance, billed as Condell, combines all the immortal actors who spoke Shakespeare's lines, an embodied play-spirit madeflesh. Sir Derek Jacobi, a fussy hurriedPrologue with an umbrella, rises into greatness on his own voice.

It would be a spoiler to talk about all the things the characters accuse each other of (and look who does the accusing). The central story is the succession--who will reign after Elizabeth?--and children and parenthood are as central to this movie as poetry. Who is the father of a child, who is the father of Shakespeare's poetry, and who can lay claim to their children? The great child is England, acted by the eager faces of the people of London, a reluctantly enchanted handful of poets, the tragically young conspirators Essex and Southampton, a delusional queen.

A story that flips around over half a century takes a lot of setting up, and the first few minutes are as confusing as a Shakespeare play. Fitting characters into this Procrustean plot, Emmerich happily gives some less than their due. Queen Elizabeth is raddled rather than regal and Sir William Cecil is a one-note Puritan.

And what about Shakespeare? Rafe Spall of Shaun of the Dead does a neat turn as cocksure, clueless W.S. of Stratford. His Shakespeare knows he's born to be the hero—writer John Orloff gives him a wonderful early scene, "I'm an actor. I crave to act"—but the real joke is his striking physical resemblance to W.S. How can the spitting image of the Bard be such a con man?

It's a big, overstuffed, sometimes untidy movie, and you may be infuriated by it. But you'll want to see it.

I want to see it twice.

Published on October 27, 2011 22:00

No comments have been added yet.