Palace on stilts

“A brilliant day. The sun smote me as I descended the steps. We walked to the curious high swinging gate like a waving symbol and a warning taller than a hanging man whose toes almost touched the ground; the gate was as curious and arresting as the prison house we had left above and behind, standing on the tallest stilts in the world.” (The Palace of the Peacock, p. 21)

Everywhere in The Palace of the Peacock, we are asked to look up. At the sky, at the sun, at swinging gates, at trees, birds, waterfalls, stars, comets, at dangling nooses, up ladders, and even at houses built on stilts.

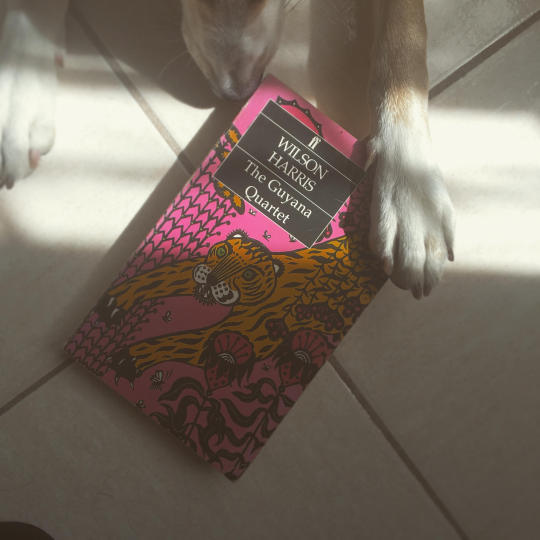

Why a novel? Why bring a mas based on a book? And a book by an author with a style as dense and formidable as Wilson Harris? Why? Because this is a book that teaches us to levitate. Consider its scenes of elevation, literal and spiritual, as embodied by the quotation above. But as is typical of Wilson Harris nothing is one thing or another. What is dead is also alive; what is up is also down:

“The whispering trees spin their leaves to a sudden fall wherein the ground seemed to grow lighter in my mind and to move to meet them in the air.” (28)

“Every boundary line is a myth,” (22) the character called Donne warns. We are in the landscape of the mind, a “chaos of sensation” (24), a collage, a mosaic, a painting. We are journeying through a “masquerade of appearances” (13), the expanse of the fabric of the universe.

Reading The Palace of the Peacock is, therefore, like encountering a riptide. You have to cut your way through it diagonally or else you drown.

This is not prose. This is a book-length poem that stretches its language; a rich stew in which the twins of past and present are blurred, as the Mayans might blur them. People appear, each a “character-mask” (8), each both dead and alive, dreaming and awake, traveling yet not moving, dancing yet still, doing things, finding things, yet not finding.

Slowly, the novel reveals its secret: the person who is at the center of it all, that person emerges—like the star-studded peacock that gives the book its title—at the very end, making it plain that we have been reading a self-portrait in the form of a written mas.

Here is a book that challenges the idea of the novel, turning it into a poem, a painting, a dance on stilts, a history lesson, a Carnival of the soul. It seeks now, through this band of Mokos, an audience.

— from my talk given at the launch of ‘The Palace of the Peacock’, this year’s Carnival band by Moko Sõmõkow, at Granderson Lab, Belmont, February 14, 2019.