Dispatches From Siberia #51: On Dualities

Last weekend, I traveled to a memorial service that was simultaneously among the most beautiful and heartbreaking things I’ve encountered. Heartbreaking, of course, because of an untimely death. But beautiful in the way he was remembered and what that remembrance means.

The service honored a teacher and mentor. I won’t name him here because his closest loved ones are grieving deeply, and their grief is not mine to co-opt in a blog post. But my experience there was meaningful and profound and, I think, worth sharing.

The reason for such impact is simple: the man we honored was someone who devoted the greatest part of his life and work to the elevation of others. Our cultures, our work, our salaries, classes, our resumes and CVs, our families, even our faiths often suggest or flat demand that we achieve without ceasing, and that we broadcast that achievement as broadly and fully and possible. Institutions and instinct demand that we publish and earn and elevate, that we move always upward and onward. That we earn followers and views, likes, sales, grades, esteem, credentials. It’s all marked and quantified—measurable and blatant.

This week, people flooded from across the country and world to honor a man who put his own energy and force behind the boosting of others. And at the end of his time, people stopped what they were doing and paid notice. The measurement, in this case, wasn’t in the small, daily achievement, but in a lifetime of gracious service to others.

That makes me ponder the meaninglessness of so much of what we’re asked to do, the ways in which we’re expected to behave as we navigate this life.

The ticking and marking and counting and weighing has utility, I suppose. But plenty of achievers are forgotten, in the end. Maybe it’s the givers that are worth remembering. Maybe we should place more of our focus there. All of us. You. Me. We. They. Whomever.

I cut into the regularly scheduled syllabus this week to put inject this concept into our work. We considered how it would benefit us all to remove some focus from the self, on occasion. And I could feel the questions, feel the mental flipping through the syllabi, their tentative schedule logs long demolished by the ebb and flow of the semester. I could feel the mental gymnastics trying to connect the concept of giving to points, to credit, to the ways in which it might impact the grade, the measurement, the weight of achievement.

This duality of achievement versus service has cluttered what it means to teach and learn. On Thursday, I dove into that duality. I gathered my class, collected and stashed their submitted work, and shuffled them out of our classroom—a cinderblock box painted lime green with a single large window that, on that day, was looking out over a drab, rainy streetscape with empty trashcans lingering in a jagged line along the curb.

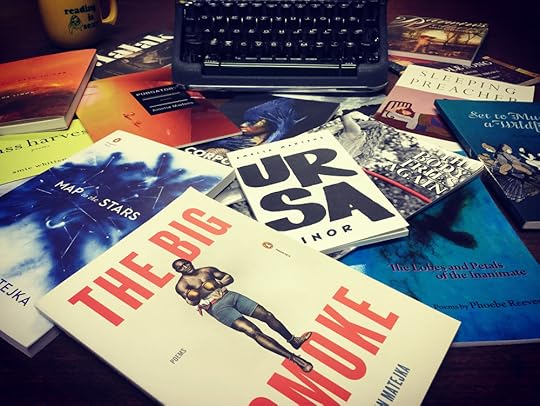

We moved to a carpeted lounge, flicked on a couple of lamps. We grabbed illicit mugs from the faculty kitchen and I made tea and espresso and plain black coffee—whatever I could muster on the fly from my office stash—and flipped on a Klo Pelgag album then passed out every collection of poetry in my possession that hadn’t already been loaned out for other projects and inquiries. For 80 minutes we read. We read quietly, and read aloud and when we felt like it (by we, I mean me, too) we stopped and wrote. Then we read more. And we listened. All the bags and laptops and phones when into a secure storage room off the main lounge. Other faculty and students squinted or slowed up while passing, but nobody paid any mind. With just books and notepads, we waded through a playground of beautiful and wrenching and exuberant and crushing words

It’s the first time in a long time I’ve truly felt like a teacher, like in initiated something new in a class or group. At the end of our time, as I collected the stack of poetry books, I heard one student say on her way out of the room, “I didn’t expect to have so many feelings in a class.”

A classmate responded, “Yeah, that was intense.”

Among the artifacts of our poetic exploration.

There’s no place on a syllabus for intensity. For the number of feelings encountered during a meeting. No line on a resume. But it’s the most worthwhile thing that’s happened in my work this semester. Maybe this year. This decade, perhaps? But again—I count, I weight. I can’t help it because none of us can. What did I accomplish? What didn’t I?

In the best of circumstances, this idea of teaching and learning is hard to navigate. The best of circumstances are a gone glint in someone’s eye, at this point. Last week, my colleagues at a campus down the street received a memo from their new president, reminding them that denim is forbidden in the classroom because their “customers” deserve a professional experience.

I loathe to think what my life might have become, how much I’d have lost, if my best teachers had been asked to treat me as a customer. I loathe thinking of what’s happening to the generation for whom this thought is reality. Last week, too, a family member asked for some suggestions to help with a disciplinary issue in a middle school class. The administrator’s suggestion was to ask the middle schoolers what they feel like learning and adjust the curriculum to match.

I’d repeat that for emphasis, but I can’t bring myself to type it again—or even to copy and paste. You can read it again, if you need to. I can’t bring myself to give that idea any more space.

Everything transactional. Everything measurable. And if the weight is not substantial, the venture and the venturer are dismissed.

I’ve told my writing students this, and I’ll share it again here: if there was no assessment, no measurement, no accreditation or institutional development criteria to advance, I know exactly how I would teach. If my goal was simply to help students learn something, to discover, to equip them to seek without ceasing and to develop the sort of curiosity that will make their lives feel rich, we would do this:

We would meet for two weeks. We would glide through a crash course of reminders on all the techniques and styles at their disposal. Then, I would lead them to a library and abandon them. I’d tell them to find the novel of a literary icon, and then find one by someone who looks nothing like them. I’d ask them to find a story collection released this month, and one written a century ago. I’d ask them to find a memoir by someone whose ideas shock or terrify them. I’d ask them to find an essay collection by someone who inspires them. I’d ask them to read an indie poetry journal and then a collection by someone in the canon. I’d ask them to read a themed poetry collection about a topic they don’t understand. I’d ask them to find something that was self-published and something translated and something that just flat confuses them.

And I’d send them home to read.

Then, I would ask them to write when they are inspired or aggravated—not to worry about the genre or classification—just to write. I would sit in the classroom every day and wait, available to help them process what they’d read or written. To show them how to ask great questions when getting feedback from a classmate, when they felt ready. No workshop. No red-pen markups. There’s a place for all that, eventually, but if they’re going to learn or discover, I don’t want roots in antagonism. They’ll get enough of that, eventually. In November or April, we’d come back together and read to each other, out loud. We’d read from each other, silently. Maybe we’d write reflections.

I promise, that group of writers would be off to a good start.

But none of that is quantifiable. None of it leads to a resume line, or stacks a skill on top of another skill, which justifies the stacking of a course atop another course.

This is all hard and imperfect and will always be. But I can’t help—this week in particular—thinking about how the work I do can be shaded more fully toward the elevation of others, toward the real work of teaching that rests in there somewhere, behind the transactions and the dress slacks and the scales and percentages. It’s in there, I truly believe—a way to elevate the imperative to give—and though the digging might be hard, I’ve got a newly clarified need to seek out that path.

#

Brooks Rexroat lives and writes in Owensboro, Kentucky. Contact him at: brookspatrickrexroat@gmail.com