A Picture of the Coronavirus at Work

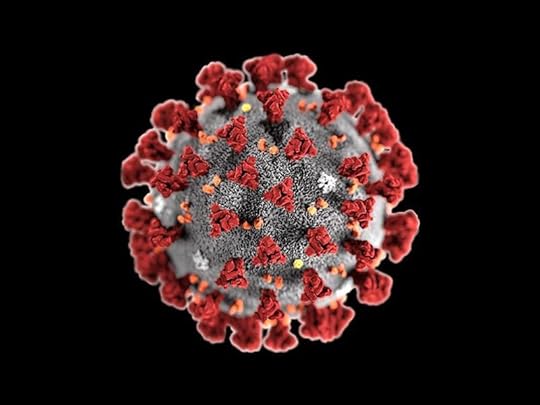

- CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM / Public domain Above is the familiar, iconic electron micrograph of the corona virus that causes the disease COVID-19. Here's what we can learn from the picture. First, it is a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) that shows the three-dimensional surface of the virus. It is a sphere that is extremely small, 1000 times smaller than the cells it invades. We cannot see it under an ordinary microscope that uses visible light, because it is smaller than the shortest wavelength of visible light. It is one thousandth the size of an ordinary cell.

- CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM / Public domain Above is the familiar, iconic electron micrograph of the corona virus that causes the disease COVID-19. Here's what we can learn from the picture. First, it is a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) that shows the three-dimensional surface of the virus. It is a sphere that is extremely small, 1000 times smaller than the cells it invades. We cannot see it under an ordinary microscope that uses visible light, because it is smaller than the shortest wavelength of visible light. It is one thousandth the size of an ordinary cell.Under an electron microscope the image is all gray, (like the background) no color. It is colorized later by people who are trained to recognized structures distinct from a gray background so that that average viewer can easily see them. Viruses have no color because the wavelengths of all the colors of the rainbow (visible light) are longer than the virus. So the color of a structure is chosen to stand out by the colorer. We know its size from the magnification of the electron microscope. An electron micrograph captures an image of a specially prepared specimen in a vacuum. It cannot show us a living cell, only a frozen snapshot.

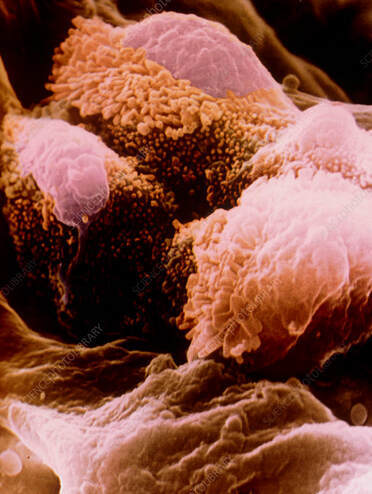

Colored SEM of cells in alveolus of the lung Credit: Prof. Arnold Brody/Science Photo Library This is a scanning electron micrograph of the healthy cells lining an air sac (alveolus) of the human lung. At the center left and top are two type-two cells typically attacked by the novel coronavirus. They are covered with hair-like structures (microvilli) and secrete a substance that that reduces surface tension in the air sac and prevent it from collapsing. The magnification is x 5,100 at the photograph's 6 x 4.5 cm size.

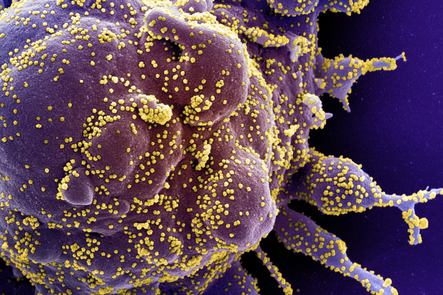

Colored SEM of cells in alveolus of the lung Credit: Prof. Arnold Brody/Science Photo Library This is a scanning electron micrograph of the healthy cells lining an air sac (alveolus) of the human lung. At the center left and top are two type-two cells typically attacked by the novel coronavirus. They are covered with hair-like structures (microvilli) and secrete a substance that that reduces surface tension in the air sac and prevent it from collapsing. The magnification is x 5,100 at the photograph's 6 x 4.5 cm size.  Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases. This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of a lung cell infected with the virus the causes COVID-19. They are the yellow dots on the surface of the cell. You can see how small they are compared to the cell, which has many projections to increase its surface area for the exchange of gases (oxygen for carbon dioxide), the crucial job of the lungs to keep us alive.

Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases. This is a colorized scanning electron micrograph of a lung cell infected with the virus the causes COVID-19. They are the yellow dots on the surface of the cell. You can see how small they are compared to the cell, which has many projections to increase its surface area for the exchange of gases (oxygen for carbon dioxide), the crucial job of the lungs to keep us alive. The spikes on the surface of a COVID -19 coronavirus (you see in the first picture) are proteins that fit like a piece of jig-saw puzzle to receptor proteins on the surface of the host cell. This fools the cell into inviting the infectious enemy through its membrane. Once inside, the coronavirus finds a ribosome, a small organelle that makes proteins from RNA codes specific to the organism. (RNA is a single strand of nucleotides with the same sequence as the organism's DNA) . The coronavirus, which is basically RNA with a protein protective coating, is able to use the replicating machinery of a ribosome to make copies of itself. The newly minted coronaviruses then squeeze through the cell membrane like tiny buds. In the process, it interferes with the functioning of the lung cell to provide us with oxygen.

Meanwhile lots more of the virus are being replicated inside the cell. Upon re-emerging outside the cell, each virus particle is now free to infect other cells in the body and be shed from the person in tiny drops of moisture from speaking, sneezing and coughing.

Self-replication is an essential activity of all living things. Is a virus a living thing? Are there any free-living viruses? All it can do is replicate itself in the cells of a living host, which range from the smallest bacteria to us. It doesn't have metabolism, so it doesn't "eat." As long as it doesn't come across an outside environment strong enough to destroy is complicated molecular structure, it will exist (not "live") as long as it needs to exist until it encounters a receptive host.

It's amazing to see the magnitude of the infection in the microscopic world of a single sick cell.

Published on June 15, 2020 21:00

No comments have been added yet.