Exiles (For Brad Watson)

Gessner

EXILES

In Honor of Wilton Brad Watson 1955-2020

In 2003 I underwent a sea change, though I still live by the same sea. That was when I left my home beach on Cape Cod and moved a thousand miles south to an overdeveloped island off the Carolina coast. It was a hard goodbye, one necessitated by money, work, and health insurance, paralleling a career move my father made, from Massachusetts to North Carolina, at exactly the same age. Though in moments of melodrama I felt I had made myself into an exile, I knew it wasnât all that bad. But there was something in the way of surrender to the move.

This is overly-dramatic, I know, but during those first years I couldnât seem to shake thoughts of displacement. I remember one morning on the beach I heard a loon cry, and though my field guide told me that those birds winter as far south as Florida, the eerie yodeling sounded out of place, a melancholy song of the north. I watched the pelicans dive for a while, twisting down into the water, following their divining rod bills, and thought about how exotic they would look plunging into Cape Cod Bay (though the rumor is they have now made it as far north as Long Island.) Then I headed back home and made some coffee and got to work on my novel, a book set in the North that I was writing in the South. I had trouble dredging up the specifics of my old home, despite combing the dozen or so journals on the bookshelf next to my desk, and so, procrastinating, I checked my e-mail.

What I found online was not so different than what I’d found on the beach: It was clearly going to be one of those days full of coincidence, the kind you’re not allowed to have in fiction but that happen often enough in life, when many of your worlds–in this case electronic, avian, and emotional–insist on playing the same theme. And there it was. An email from my old friend, Brad Watson, who had written a beautiful Southern novel while living in the North. The e-mail was an exciting one: he had quit his teaching job and moved to a cabin in Foley near the Gulf in Southern Alabama to be close to his son, Owen. He wrote:

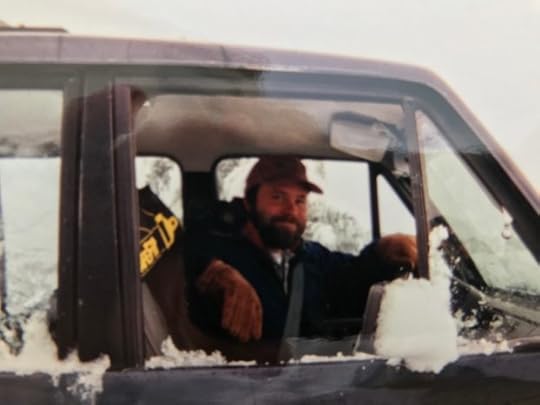

I am now officially a hermit, and man you’re right, it feels good, feels right. The beard’s back after an eight month absence, hair sticking up all around the bald spot like wild grass on the rim of a blighted field. This old house smells like woodsmoke. The other night, Owen said, “The smell of this house reminds me of the smell of a house on Cape Cod,” and he was talking about the old Gessner house. So I suppose right now I’m the southern version of you in those days.

In another parallel, it had been Brad’s first book of Southern short stories that had led him north, when he was offered a five-year position as a Briggs-Copeland lecturer at Harvard. Brad liked to play up the Beverly Hillbillies aspect of this move, the country bumpkin strolling into Harvard Yard with a piece of straw between his teeth. Of course he was anything but a rube, and became one of the school’s most popular teachers, though he did make one bumpkin-like decision in choosing to live, not in the urban mix of Cambridge, but down near me in the wilds of Cape Cod. We were introduced by a mutual friend, a Southern writer in fact, and met at a drunken dinner at Bradâs house with our wives where he served Coq au vin, a slow-cooked brothy chicken that you could gum off the bone. We drank too much–this would become a repeated theme–and at one point he admitted he had a 26 year old son, Jason, from his first marriage. I did a little math and figured that meant he’d had his son when he was 16. “You really are a Southerner,” I blurted. Not the kind of thing you want to ever say but especially not on a first friend date. When he laughed instead of scolding me for my stereotyping–a scolding that might have actually happened with other oversensitive Southern writers of my acquaintance–I knew it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

At the time we were living a half hour away in East Dennis on the Bay side of Cape Codâagain playing north to his southâbut the next year Brad rented a house less than mile away from us, right on the beach. It was a spectacular house where you could lie in bed and stare out at the rocks and the ocean and every now and then see a breaching whale, and where, on the rocky beach below, you could find stranded loggerhead or Kempâs ridley turtles and the cadavers of coyotes and winter shorebirds like dovekies and gannets. The bluff, which you could see out of the western windows of the house, was where I would eventually set my Cape Cod novel, and the wind would be more than a minor character in that novel, since it never stopped whipping across the Bay and hitting the leeward side of the house with enough force to make it hard to open the door in winter. The wind drove Brad’s wife crazy and made her miss the South, but it also leant a drama to the place that verged on melodrama, as if they were living inside the pages of Wuthering Heights.

It’s hard not to romanticize the year we lived down the street from each other, and I need to remind myself that there were problems for all of us–career-related, familial, marital, even chemical–that made the year less than romantic. But I still can’t help but look back somewhat hazily on that time: I had spent my twenties writing in isolation with no literary community at all, and now, suddenly, I was part of a tiny writing community, a Bloomsbury on the beach. Brad and I would go for runs around the cranberry bog and bat back and forth the various plots of the various books that were obsessing us, and often I would find that he understood the literary allusion I was making or that I understood his, or that we had read the same book, or would soon read that book on the other’s suggestion, and before I knew it we were having, between heavy breaths and plodding steps, a real-live bona fide literary discussion. One thing I loved about those runs is the way our talk ranged from the high to the low. Low crude jokes, occasional high insight. And plenty of shoptalk too: books, sure, but also ways to get ourselves started, that is to make sure we sat ourselves down and got to  typing each day.

There is no Algonquin Round Table without booze, and drinking was also part of the year’s ritual. (I later suggested that Bradâs biography should be called The Sodden Heart.) As it happened there was already a great tradition of Cocktail Hour on that part of Cape Cod. Not much more than a mile way from where we lived the great New England nature writer John Hay had shared drinks with the displaced Southern poet Conrad Aiken in 50s, back when Aiken was collecting the second of his Pulitzer Prizes and still considered on par with T.S. Eliot. No living writer–not Bernard DeVoto with his evocation of the perfect martini or the liquor-soaked Hemingway or even Aikenâs protégé Malcolm Lowry–could match Conrad when it came to the daily glorification of booze. “The ritual of cocktail hour represents the communion of all friendly minds separated in time and space,” wrote Aiken. His poetic elevation of cocktail hour grew so famous that even the napkins used for the Aiken’s pewter drinking goblets later found their way into an Updike novel.

Our nightly boozing wasn’t quite so glamorous. Brad would sip whisky, slouched in his chair and I would swill many beers, and my wife Nina would drink wine. If this wasnât the stuff of literary legend, it worked okay for me. There I was, living on my favorite place on earth, the closest thing I had and would ever have to a Walden, and now I also had a new and dear–and bookish!–friend right down the road, someone who also understood the daily wrestling match with words, and also understood the constant career disappointments–the envy and bitterness and failure, the way the game was so obviously rigged–and who I could drink and laugh about all of it with.

Of course nothing this simple exists for long, if it ever did exist at all outside of stray and random moments. It’s easy enough to make a golden age once the sloppiness of the actual time has passed. By the next year Brad had finally moved up to Cambridge and our friendship had begun to become a long distance one, which it would remain. Brad’s time at Harvard was too complicated to call a triumph, but there were moments of triumph. One was when he imported two of his favorite Southern writers, Barry Hannah and Padget Powell, to speak to a packed house in the Thompson Room below a portrait of Teddy Roosevelt. Hannah, who was very sick at the time, teared up at the podium, saying that he felt “like Quentin Compson come to Harvard,” and that now he knew “this southern boy has made good.” A year later Brad’s five year stint in Cambridge ended and he headed back to the South to teach. Since then I have seen him only occasionally and for very short periods of time.

In the meantime Brad had gone a good while between books, not out of any traditional version of writer’s block–that is out of paucity–but rather out of excess, many different plots competing for prominence in his mind. He finally bore down, and finished his novel, The Heaven of Mercury, during his last two years in Cambridge. Of course, strategically speaking, Iâve gone about this essay all wrong, and by so excessively romanticizing my early friendship with Brad you will never believe me when I tell you that the book he produced during those years on the Cape and in Cambridge is one of our greatest contemporary novels. It will sound like hokum, like nonsense, or, even worse, like that lowest and most deceitful of things: a blurb.

But it’s true. Writers tend to be friends with other writers–it just eventually ends up working out that way–but it doesn’t always happen that your favorite books come from your favorite people. I’ve read a lot of friends’ work that I’ve had to politely praise, but Brad’s book was an exception. I had heard him talk about it often enough on those runs around the bog, but even bad writers can sometimes talk beautifully about their work in abstract. But the thing itself, the final book, was, and remains, a delight. The bookâs main character, Finus, is a man of deep wistfulness and melancholy, a man who admits his own “inability to see the world except through the crinolated filters of self-consciousness need.” But within the bookâs pages Brad himself, as if fulfilling Finus’s wish to “not be who he was” flies from character to character, inhabiting each deeply, from Finus to his unrequited love, Birdie Wells to Birdie’s maid, Creasie, until we experience a full and varied, and yes, slightly sodden, world. There is an element of caricature–like Finus’s mother a “poor God-ravaged grackle of a woman,” or the horse named Dan: “A long, slow fart flabbered from the proud black lips of Dan’s hole…,” or Mrs. Urquhart’s heart, like a “shriveled potato”âand an element of the grotesque, like the scenes of necrophilia or the final mystery of an actual shriveled heart. But this is a humanized grotesquerie. Critics drew comparisons to the usual Southern suspects, Faulkner and O’Conner and Welty, as well as throwing the name Marquez around, due to the magical scenes at the end. But I was reminded of the early Cormac McCarthy, not the cowboy stuff, but the books Brad had turned me on to, the McCarthy of Child of God and, less so, of Suttree. The difference, to my mind, was that Brad’s stuff was better: it scumbled the surface of language and surprised in a similar fashion, but as well as being a pleasure on a language level, it told a story about very human characters, something McCarthy, for all his achievement and renown, does not.

Happily, Bradâs accomplishment did not go unrecognized. Heaven was a great critical success and was a finalist for the National Book Award. For my money, it should have won.

I was quite proud to be mentioned on the acknowledgements page, with a phrase that might have easily come directly from one of our runs. Bradâs nod to me was a simple and practical one: “Thanks to David Gessner for urging me to get on with it.”

* * *

And so Brad was a role model as I sat at my Southern desk staring at my newly-purchased Southern Computer in my Southern Town and trying to resuscitate the dead journal details and to create or re-create my days on Cape Cod. I wanted to write of my fictional Cape Cod in a gritty and particular way and I could think of no better models than the quirky Southern novels I admired, Bradâs not the least among them. Of course there is a tradition of writing about places after you have left them, a tradition every bit as strong as that of writing while in a place. Itâs just that Iâve never been of the Hemingway school, the exile school, evoking childhood Michigan from Paris, but of the Thoreauvian one, writing of a place while still in the infatuated midst of it. So some adjustment was necessary. But there I was, after all, and I wasnât going to be going back any time soon, so I thought I might as well make something of my exile.

The truth is that the more I worked, the more I saw the advantages of holding a place at armâs length. For one thing, now that it was in the past tense, I could see the time we were on Cape Cod as a kind of story with a beginning and end, an epoch in our lives, and could make sense of it in a way I never could while in its midst. And mine wasnât really much of an exile: We would be going back North in the summers, after all, and I could imagine a benefit to this pulsing, to going away and coming back, to seeing a place from afar, and so seeing it new. And this annual cycle included the re-infatuation of seasonal return: my own return right after the bank swallows come back, then the white clouds of beach plum blossoms in later May, the prairie warbler with its xylophone song, the fox kits scampering up the jetty rocks to their den. In fact, thinking about these things made me decide it was time to stop equivocating and get down to my real business, that of imagining Cape Cod. Enough throat clearing. Exile is just another excuse for stopping at the imaginative threshold, the sort of excuse we are always using to stop ourselves short. As Samuel Johnson said, anyone can write anywhere and any time, as long as they set themselves âdoggedly to it.â Or, as Brad might have advised me: time to get on with it.

P.S. I wrote the above a while ago, Iâm honestly not sure how long. About a year ago, in fact very close to exactly a year ago, Brad came down to visit me from his home in Laramie to the house where I was staying in Boulder, Colorado. With Boulder friends our get-togethers usually involve some sort of vigorous hike or bike, followed by a couple beers. But Brad would be arriving at noon and not leaving until the next morning and he had not brought any work out clothes. What would we do for all that time, I wondered. Of course the answer should have been obvious: we would drink. Drink and tell stories.

At one point a Boulder friend, Dave Smith, came over for a visit and ended up listening to us for a while. Brad and my topic was a competitive one and the competition hinged on which of us had written more unpublished books. We werenât talking about mere drafts. We were talking about books that we had worked on over the course of years and had, in our minds at least, finished but that were never published. As I remember it, I âwonâ with something like eight books to his seven. My list included the novel I mention in the essay above. Iâd like to find out more about what Bradâs list included.