Ghosts of Gettysburg Haunted Daytrips: Manassas

There are a number of Civil War sites in America that were unfortunate—or cursed—enough to have more than one massive battle rage across their landscapes. Manassas was one of them.

The reason Manassas Junction was important would not have mattered to the earlier armies of the American Revolution or of the Napoleonic Era. It wasn’t until the first half of the 19th Century that a relatively new invention appeared upon the scene and changed warfare: the steam locomotive. Miles and miles of track had been laid, and the railroad’s worth in peacetime as a carrier of goods and people had been proven. Naturally, when war broke out, railroads were looked to as an expedient extension to the supply lines of an army. They added a relatively fast-moving vehicle to bring food, supplies, arms and ammunition to the soldiers in the field, compared to the plodding wagon trains that were limited to the walking speed of mules or horses. Occasionally, as would be seen at the first Battle of Manassas, they were helpful in bringing reinforcement troops to the battlefield.

The Battle of First Manassas

The Manassas junction of the Orange & Alexandria and Manassas Gap Railroads and its location just a couple of days march from Washington made the northern leaders extremely nervous when, in the early summer of the first year of the war, Confederates began to converge on the junction near the flowing waters of Bull Run.

Lincoln directed General Irvin McDowell to come up with a plan to take his 35,000 freshly recruited, enthusiastic, Union volunteers, and oust the 21,000 Confederates established around the junction. The “rebels” were commanded by General P. G. T. Beauregard, the conquering hero of Fort Sumter. Some 11,000 Confederates, under General Joseph E. Johnston, were in the Shenandoah Valley waiting to reinforce their comrades at Manassas should they be needed. A large Union force was placed, so as to prevent that from happening.

The green Federal recruits began their march from their camps near Washington to Manassas on July 16, 1861. Unaccustomed to disciplined marching, it took them days to cover the thirty or so miles to the future battlefield. They would fall out to pick blackberries or fill canteens when they felt like it. A large contingent of politicians, and their ladies, buggied out from Washington to watch the first battle, and the predicted easy Union victory over the hayseed rebels.

Sadly, shockingly, their impressions of a battle and its aftermath were woefully mistaken. Soldiers were actually hurt, some even killed, in much larger numbers than any of the politicians, whose rashness got them into this war, had expected. Death, in all the ghastly, hideous forms that can be brought on by mortal combat, took them by complete, horrifying surprise.

Part of the problem was that McDowell’s elaborate battle plan was far too complicated for the raw troops and junior officers he commanded. Feinting attacks and wide sweeps around the flank would be accomplished eventually in this war, but not until the armies and their commanders had more experience.

The Confederates were, for the most part, on the defense and parrying attacks—counter-punching—was easier for green troops. Just when the Yankees were about to defeat their southern counterparts, Johnston’s men came riding in on the railroad cars, fresh troops to turn the tide. When Confederates found themselves on the attack, at the end of the battle, they were aided by two things: the inability of their enemy to withdraw in an orderly fashion under fire, and their commanders’ mistake of not allowing for several avenues of retreat. When a lucky shot overturned a wagon on a bridge on the road back to Washington, it clogged the retreat for the Union Army and their political observers. The ensuing panic was overwhelming. The same march that took days to get to the battlefield was covered in hours on the hurried, panicked retreat back to Washington.

[image error]Stone Bridge to Washington

Casualties seemed horrendous to a country not yet accustomed to war. The final toll for killed, wounded and missing was higher than in any other battle fought by an American army to date. Confederates suffered 1,750; the Union army, 2950.

Yet the casualties that horrified the nation from the first battle near Manassas Junction would be dwarfed a little over a year later when the two opposing armies fought there again.

The Battle of Second Manassas

After McClellan’s unsuccessful Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, in which the Confederates drove the Union army from the doorstep of Richmond, Lincoln brought General John Pope from the western theater of the war to command in the east.

The wounding of General Joseph E. Johnston on the Peninsula brought in Robert E. Lee to command the Army of Northern Virginia, the largest army in the Confederacy.

On August 12, Lee received intelligence that McClellan was heading from the Peninsula to reinforce Pope. Lee planned to attack before Pope could be reinforced by McClellan. Fortunes of war would dictate otherwise.

General J. E. B. Stuart, Lee’s renowned cavalry commander, was nearly captured by Yankee troopers at Verdiersville on the morning of August 18. Stuart got away, but the Federals captured some of Stuart’s personal items, including his haversack with Lee’s orders in it. Now Pope knew some of Lee’s aggressive plans and withdrew his army to north of the Rappahannock River.

Heavy rains swelled the river so that it was impossible for Lee to get to Pope. Stuart missed capturing Pope in a raid of his own, but in an ironic twist got Pope’s dispatch book with marching orders and troop strengths. Now Lee had some valuable information of his own.

Though the tactics manuals of the day frowned upon a commander splitting his army in the presence of the enemy, it was to become one of Lee’s tactical trademarks. On August 25, he sent Jackson, his 27,000 men and 80 pieces of artillery on a 50-mile march around Pope’s right flank. In just two days of marching, Jackson struck behind Pope’s lines and seized his supply depot at Manassas Junction. Hungry Confederates ate everything they could then burned the rest of Pope’s supplies and went into position behind a crossroads called Groveton near Manassas Junction.

When Pope realized that Confederates had turned his flank and attacked his base of supplies, his response was to march on Jackson’s men at Manassas. He hoped to hold them up until McClellan arrived and before Lee and Longstreet could cross the mountains to the west. It was what Lee feared.

As part of Pope’s army marched along the Warrenton Turnpike through Groveton late in the afternoon, August 28, 1862, his officers saw a lone Confederate horseman brazenly ride out to within rifle-range and observe the column. The lone rider returned to the woods near the Brawner Farm and told his subordinate officers, “You may bring up your men, gentlemen.” The single horseman making a personal reconnaissance was Stonewall Jackson, himself.

What ensued was the large-scale equivalent of an old-fashioned duel. Two of the most vaunted units in either army were involved: Jackson’s own Stonewall Brigade and some tough Midwesterners who would soon earn the nom de guerre, The Iron Brigade. The Northerners first volley was fired at 150 yards, yet the Confederates continued to advance to within 80 yards before they fired their first volley. For twenty minutes the first units in the battle volleyed toe-to-toe, suffering horrendous casualties.

As the sun slowly sank, more units were thrown into the fight by both sides. They blasted away at each other from point-blank range: one Union colonel called the participants “crowds” of men firing at each other from 50 yards. Neither side wanted to withdraw. Finally, darkness forced an end to one of the most intense battles—for its duration—in the war to date.

Jackson pulled his men back to an abandoned railroad bed—embankments and cuts but no ties or rails—which made for “pre-fab” entrenchments and defensive breastworks. He placed his artillery behind his 20,000 infantry and secured his flanks with Stuart’s cavalrymen. Now, all he had to do was hold off twice as many Yankees until Longstreet and Lee arrived.

[image error]Unfinished Railroad Bed

At 5:30 a.m., August 29, the Federals advanced. Pushing their way through dense woods, they engaged the Confederates along the railroad bed. By mid-morning, more Federals began advancing, bent on Jackson’s destruction. Suddenly they were confronted by a large number of the enemy right before them: Longstreet had arrived.

Longstreet’s line hooked up with Jackson’s right flank completing an “L” shaped line.

Pope sent confusing orders to one of his commanders and 10,000 men of the Fifth Corps stood idle just a few miles away.

If Pope was having trouble with subordinates attacking, so was Lee. A third time Lee requested Longstreet attack, but was disappointed. Nightfall ended the ferocious fighting of August 29.

Before noon on August 30, Pope began to receive erroneous reports that Jackson was in retreat. By early afternoon he had convinced himself that all he needed to do was pursue and destroy a retreating column of Confederates. As his troops advanced toward the railroad bed, they were met by volleys from the enemy, obviously not in retreat, as determined as ever to hold their position.

Fighting was particularly fierce in the lowest section of the railroad embankment known as “Deep Cut.” The Federals nearly broke through a gap in the Confederate line at a place called “The Dump,” where the defenders ran out of ammunition and hurled rocks at the Union troops. So close were their battle lines that one Confederate officer recalled the opposing flags “were almost flapping together.”

While Jackson’s men doggedly resisted Pope’s onslaught, Longstreet still held off on his attack. Meantime, a portion of the Union troops in front of Longstreet were mistakenly withdrawn, leaving one lone unsupported battery of artillery to defend the Federal flank.

The commander of the battery realized the extreme danger and sent an aide to find some troops. Two infantry regiments—Zouaves from New York—dressed in their gaudy uniforms of red pantaloons, white gaiters, and tasseled fezzes, hurried literally to their doom. They arrived in position just in time to face Longstreet’s massive assault.

Twenty-eight thousand Confederates bore down on the New Yorkers, approximately 1,000 strong. In five minutes the 5th New York lost 123 men killed. After all the horror and slaughter of the Civil War was finally tallied, the Zouaves, according to some historians, held a grisly record: They lost the highest number of killed in any infantry regiment and any battle of the entire war.

Longstreet’s men pushed on toward Henry Hill, landmark for the first battle of Manassas in 1861. Atop the hill were two brigades of the Pennsylvania Reserve Division, which were ordered forward.

The opposing lines met at the Sudley Road where Yankees seized the washed-out depressions as cover. More troops from both sides arrived and the Union troops, after having stalled Longstreet’s attack, began to withdraw. Finally, sunset brought an end to the fighting.

[image error]

Casualties were high. Of the 70,000 Union troops present, 1,750 were killed, 8,450 wounded, and 4,250 missing; the 55,000 Confederates engaged lost 1,550 killed in action, 7,750 wounded, but only 100 missing in action.

Undeterred by the 9,400 casualties, Robert E. Lee turned his army’s marching columns northwards and began his first invasion of the enemy’s territory.

(For expanded accounts of the Battles of First and Second Manassas, see Civil War Ghost Trails and Cursed in Virginia by Mark Nesbitt.)

Directions to Manassas, Virginia: Take Route 15 South from Gettysburg. At Frederick, continue on I-270 South to I-495 South to I-66 West to VA-234 North (Exit 47B) in Gainesville, Virginia. The Manassas Visitor Center address is 6511 Sudley Road, Manassas, Virginia, 20109.

For an alternate route, the next blog will be on Ball’s Bluff Battlefield, which is on the way to Manassas if you prefer back roads!

Ghost Stories of First Manassas

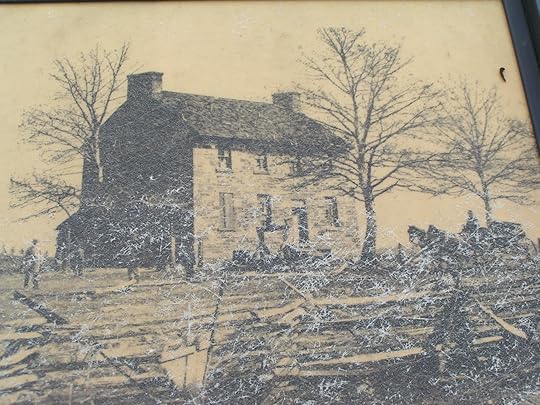

The Stone House is a battlefield landmark closely related to the first Battle of Manassas. It has a sordid past and mysterious happenings associated with it. Built in 1848, the pre-Civil War history of the house is checkered. It was once a wagon-stand, tavern and inn at a toll stop for travelers on their way to and from Washington. According the Park Service’s brochure, it catered to rough-and-tumble, liquor-drinking cattlemen and teamsters. Park historians have documented that in addition to once being a private home, the building was used as a hospital during both battles. Witnesses after the first battle recalled seeing wounded men in the mud of the dirt-floored cellar, as well as throughout the rest of the house. One witness counted 32 wounded in the house at one time, many “mangled” by artillery fire. Some of the dead had not been removed. The same scenes revisited the house during the second battle. At least two wounded men from the 5th New York Infantry—Privates Charles E. Brehm, age 21, and Eugene P. Geer, age 17—left their names carved in the woodwork of the house. Brehm survived; Geer died.

The Stone House at the time of the battle and The Stone House today

The Stone House at the time of the battle and The Stone House todayParanormal references to the Stone House go back to 1866 when Confederate veteran and novelist John Esten Cooke referred to it in his book Surry of Eagle’s Nest. He called it “The Old Stone House of Manassas,” or, more ominously, “The Haunted House.” Early in the 20th Century a story emerged of a curse placed on the house and the family that lived there after the war. Henry Ayres owned the house in 1902 and upon his death bequeathed it to his son George who, perhaps in an effort to attract tourists, placed artillery shells in the walls where some had struck during the battle. Legend states that the family lost more than six of its members to death in a relatively short time. No more is known about the alleged curse.

David Roth, in “Blue & Gray Magazine’s” Guide to Haunted Places of the Civil War in 1986 wrote about the negative energy in the house that is felt by many. Visitors sometimes feel a distinct pressure from invisible hands pushing them down the stairs from the second floor.

In July 1994, I received a letter from a gentleman who wrote of his experience with pushy ghosts at the Stone House. He mentioned he had heard about the house’s history as a tavern with heavy drinkers and altercations. Though the day was hot, walking through the house he suddenly passed through one of those inexplicable cold spots. Just as he was leaving the house he was “hit hard” from behind and fell out of the house to the ground injuring his knee. In physical pain, he was also unnerved: coming from the house he heard laughter, as if a group of people were gloating over his being thrown out. He turned to ask for help only to find that no one was inside or outside of the house. He was alone.

A friend and former park ranger told me the story of a couple of rangers who were working in the basement of the Stone House. In my training as a ranger I was told that when I entered a building to always lock the door behind me so that no one could come in. This the Manassas rangers did. As they paused from their work, they heard footsteps on the floor above their heads. Thinking that somehow a visitor had gotten into the house, they went upstairs to find no visitor and all the doors still locked.

In his book Civil War Ghosts of Virginia, L. B. Taylor, Jr., quoted a ranger as saying that people driving through the park at night report seeing lights where houses once stood. A similar story was told to me in 2010 by a woman who lived near Manassas, and was thus knowledgeable about her “neighborhood.” She was driving to an appointment and needed to drive past where the Stone House is located. She was astounded. The house wasn’t there. She was confused. Did the Park Service tear the historic building down? Had there been a recent calamity that she hadn’t heard about? Before she could fully understand what could have happened to the famous building she was past it. After her appointment, she returned the same way, perhaps thinking she might be able to stop and examine whatever remained of the structure for a clue as to what had happened to the beloved old house. As she approached the site, she was struck by one incredible thing: the house was there.

Later she told the story to friends. They were silent just a little too long. When she asked if they thought she was crazy, they answered that the same thing had happened to them. The old Stone House had vanished only to reappear a while later.

There is a phenomenon in paranormal studies known as a “warp.” It can be defined as a “rip” in the fabric of time. Is there a rip in time in the area of the Stone House that opens and closes according to some as yet unknown natural—or should I say, un-natural—law?

I can’t remember the first time I heard the story about the headless Zouave who has been seen near where the unfinished railroad crosses the battlefield of Manassas. It may have been in the mid-1970s, which would coincide with the dates I was employed by the National Park Service at Gettysburg.

First, a little historical background: In the mid-19th Century—the so-called Victorian Era—anything and everything French was popular in America, from women’s garments to military tactics. The common kepi headgear, used by both sides, was a French design. Napoleonic tactics—although outdated—were the basis for army maneuver. Captain Minié, of the French Army, improved the shoulder arms projectile—the famous “Minie ball”—to fire farther and more accurately than its predecessor (much to the dismay of those struck by it).

Some military units took the fashion statement to extremes and outfitted themselves, head-to-toe, with the uniform of the French forces in northern Africa known as the Zouaves. With middle-eastern influence, the uniforms featured ballooning pantaloons tucked into gaiters, short waist-length jackets, with looping embroidery, waistbands that were yards long, and, to complete the outfit in the most impractical way, turbaned fezzes replete with tassels swinging from the top. The unintended consequence was that worst part was that the uniforms were brightly colored—red sashes or jackets, yellow piping, bright blue, striped pantaloons—making them perfect targets when fighting in the woods and fields of America.

Some have claimed to see the ghost of a Zouave near the New York Monument, close to the site of their near-annihilation. But the Zouave I had always heard about had been seen near the unfinished railroad. Perhaps there are two, because the one I’d heard of is very conspicuously missing his head.

Along with sightings of this wraith are also out-of-place sounds, intense cold spots and weird smells like rotten eggs and a smoky or charred smell, as well as the sighting of a Confederate soldier in a butternut uniform.

According to paranormalists, cold spots are relatively common and universal during a haunting. The smell of rotten eggs—sulfur—seems to be common at Civil War battlefields and needs some explanation. The propellant for firearms during the Civil War was black powder, made up of charcoal, saltpeter and sulfur. When burned, it gives off the smell of rotten eggs.

L. B. Taylor, Jr., in his Civil War Ghosts of Virginia may have the explanation for the “charred” smell. Taylor writes of a story printed in the Washington Magazine in the early 1990s. Apparently, people on the battlefield reported localized cold spots and the smell of black powder, typical of paranormal phenomena on battlefields. But they also reported smelling burning flesh. A park ranger confirmed that visitors have randomly reported the weird, out-of-reality smells and Taylor wrote about the ranger’s “rationalization” of the smells.

Ken Burns’ classic series on the Civil War portrayed one of the more moving moments early in the war when a letter from Major Sullivan Ballou to his wife in Rhode Island was read. In flowery, Victorian prose he assures her that, should he die in the coming battle near Manassas, he will return to her as a gentle, loving spirit—his ghost—to watch over her. The sentiment is beautiful, but reality was far more brutal.

After his wounding, Ballou and a colonel were transported to the hospital at Sudley Church. There they died and were buried in shallow graves nearby. In early1862, after the Confederate army abandoned the area, the governor of Rhode Island sent emissaries to recover the remains of the two officers. As the parties dug near the church, a local girl approached and said the Confederates had already emptied the graves. They took the body of the highest ranking officer to a nearby ravine, mutilated it for ghastly souvenirs, including, apparently, the head, and burned it. The exhumation party, thanks to the girl, located the decapitated remains. But she was incorrect about the identity of the body: it wasn’t the Colonel but Major Ballou whose body had been mutilated and burned. Could this be the source for the strange reports of a “charred” smell?

A brief visit I made to the unfinished railroad in September of 2011, yielded several recordings of EVP. In the first I asked if the highest-ranking officer would speak with me and what is your name? At 4 seconds I heard the word “DeHeiser” or “DePeyster.” (Interestingly enough, there was a Union officer, a Major J. Watts De Peyster, Jr., on the staff of Major General Phil Kearny. Kearny’s Division made an attack on the Confederate line at the unfinished railroad on August 29, 1862.)

A second recording was made at 2:49 p.m. First, there’s some loud noise that cannot be recognized as words; then, at 10 seconds, a voice says, “Most definitely.” At 14 seconds there is a strange “clink” (sounding like a rail road spike being hit with a sledge hammer) that could not have come from any piece of equipment or clothing I had with me. With EVP this is not unusual: clinks, raps, clicks (like fingers snapping), bits of song, roars and whispers are often heard in the background. Where the “clink” in this recording came from is a mystery. Finally, at 16 seconds, very quietly, as if they do not want me to hear, a voice says, “you can’t talk to him.”

A final recording was made that day at 2:57 p.m. I say “Men of the 63rd you can talk to me.” At 10 seconds a quiet voice says, “He can hear us.”