Without attachment

I thought about calling this blog “closure,” until it came

to me that most people equate closure with “the end,” and I realized that there

is no end to what I’m writing about but there is a point where one can, and

must sever attachments. That’s what I’m

writing about; the end of attachment and why that is so important.

In February 1991, Operation Desert Shield became Operation

Desert Storm. One of the little noted

events that followed that action was Vietnam Veterans overrunning VA Hospitals –

not in protest but as patients – patients suffering from PTSD.

I didn’t check into a VA hospital, though it crossed my

mind. Instead, I ran an ad in my local

newspaper. The ad read, “I served in

Vietnam. If you were there and would

like to talk about it meet me at the Best Western…” and I gave the date and

time. That ad led to the founding of

Vietnam Veterans Southern Command.

Almost from the beginning, a main topic at Southern Command

was returning to Vietnam. As the

conversation became more serious, six of us decided we would do it. We set a date and began making plans. As

various deadlines drew nearer - passport applications, ticket deposits, tour

scheduling, etc. - the number committed to the trip grew smaller.

When the Thai Airways flight left LA, in early October,

1993, I was the only member of Southern Command on board. I was glad to be alone in a way that I’m not

sure I can describe, but I’ll take a shot at it.

For almost two years, I’d spent a lot of time talking about Vietnam, my

involvement there, and how it had affected me.

That followed almost thirty years of not talking about it at all. Since I had never talked about it, I wondered if,

after my long silence, I was just making up a story about the Vietnam War’s

place in my life. I was going back to find

out and if it did turn out to be a lie, I didn’t want anyone around to see my reaction. That’s why I was glad to

be alone.

I spent a sleepless night in Bangkok before boarding the

flight for Saigon (I know it’s Ho Chi Minh City to most people – I’m just not

one of them). We barely hit cruising

altitude before we began our decent into Saigon. Our final approach was long and low. As we passed over miles and miles of rice

paddies I had an overwhelming feeling that I was finally coming home. Before the wheels touched the runway at Tan

Son Nhut Airport all self-doubt slipped away; I knew that Vietnam was the most

real story in my life.

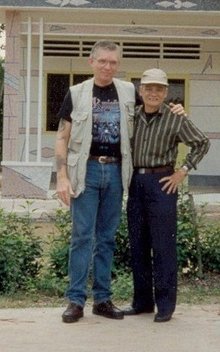

I had arranged for a tour guide/translator and a military

guide. I had high hopes of getting

inside Camp Bearcat, my home for the sixteen months I served in Vietnam. That’s why I was accompanied by General Diem,

a certified military guide, and former four-star Viet Cong General. I watched General Diem talk to the guards at

the camp, and then their commanding officer, and finally the commanding officer

of the entire base, which is a training facility for the Army. In spite of his intense effort on my behalf,

I didn’t get through the gate.

However, General Diem took me to other places and taught me

things that were far more important than revisiting Camp Bearcat. First he took me to his veteran’s group –

Vietnam Veterans of Saigon – where I was sworn in as a full-fledged member (at

the first meeting of Vietnam Veterans Southern Command, after the trip, I told

everyone about General Diem, and we voted him into our group). On my third day in Vietnam, my guide and

General Diem took me to Chu Chi. Chu Chi

was the first home of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division in Vietnam.

Chu Chi was a poor location for the Twenty-Fifth, because it

was centered over a Viet Cong underground facility that in places operated on

four levels. The VC compound at Chu Chi

had existed since their war with France and at times had housed as many as

25,000 troops.

When we figured out that the VC we were fighting lived under

one of our major headquarters, the Twenty-fifth moved to Camp Bearcat and the

Viet Cong headquarters at Chu Chi was blanket bombed by B-52s of the Strategic

Air Command, based in Bangkok.

Thousands of Viet Cong died and their bodies remained entombed until the

war ended. Then, in spite of being

almost bankrupt as a result of the war and subsequent economic embargo, the

Vietnamese Government found the funds to excavate the ruins at Chu Chi and

recover, identify, and bury with honor, all those who died there.

General Diem and I stood in silence, on the edge of that

huge memorial cemetery. When I was able

to speak, I managed to ask him, through our guide/translator, why the government

undertook such a monumental task. He

turned to me, and in very broken English, which I understood perfectly, said, “War

is not over until everyone is accounted for.”

I think about General Diem often. He is probably the most unassuming, impersonal,

yet compassionate man I’ve ever met. And,

in spite of his small stature, he is one of the most powerful. General Diem has accounted for everyone and

everything that matters in his life - that means he is no longer attached to or run by things that happened in the past. Until we account for each of those things in our life, they run us. We're kidding ourselves to believe otherwise.

I'd love it if you'd take a minute and visit my web site

then stroll over to my other blog