Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

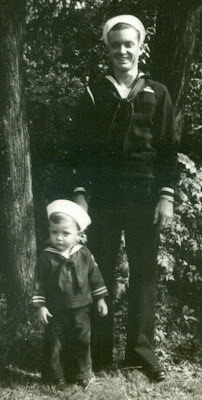

Last night I saw Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Lest you think this might be a movie review,let me say up front, it isn't. I'll justsay this about the movie; if you haven't seen it, put it on your list of moviesto see. If you have seen it you'll knowwhy it triggered the memory that led to this blog.The photo on the left was taken in1944, a couple of months after my second birthday. I'm the short sailor – the tall one is mydaddy, the second, Bertram Lee Carson. I'mthe third. I'll tell you about theoriginal in an upcoming blog. Daddy and I loved each other, but we weren'tclose. There were a couple of reasonsfor that. First, we were so much alikehe could read my mind simply by thinking what he did in the situations I foundmyself in, and second, because I failed to do the one thing he regretted neverdoing, finishing college. I graduated from high school in1960. Three months later, I enrolled inthe local junior college. I did prettywell there, so when I told my parents I wanted to go to a four year school, andI didn't want to wait until I finished at the community college, theyagreed. When I told them I'd chosenAlabama College, (now The University of Montevallo), near Birmingham, Alabamaand five hundred miles from our home in Palatka, Florida, they didn't try totalk me out of it, in spite of the extra cost of out-of-state tuition.I lasted a little over three monthsbefore dropping out a week before the end of my first semester. I'm not stupid. I belong to both Mensa and the International Society for Philosophical Enquiry. My problem was, I couldn't handle being 500 miles away from home with noclass attendance requirements. Or to putit another way, there was no time in my social schedule to attend class.A week before final grades werepublished, I left school and drove home. I pulled in my parent's driveway just as daddy was leaving forwork. He walked toward my car as Irolled the window down. A couple of feetaway he stopped, looked at me, and said, "I guess it didn't work out.""No sir, it didn't. I guess I was just wasn't ready for it."He nodded then said, "Go on in the houseand take a nap. Tell your mother I'll behome for lunch, and we'll talk then about what's next."The next thing was a job. They were plentiful in those days. I moved back into my old bedroom and that wasthat – for about a month. Then I startedthinking about my girlfriend at school, and how much I loved her. In an amazingly short period of time, I wasobsessed with the idea of going back to the school and making things right withher.A couple of days later, daddy came homefrom work, and I was waiting for him. Beforehe was three steps into the house I blurted, "I have to go back to theschool. I have to make everything rightwith my girlfriend. I know if I do thateverything will be alright… then I'll have some peace-of-mind about this."I paused and looked at Daddy, who was assilent as a statue, his eyes searching mine, I suspect for some sign ofsanity. Before he could say anything, Icontinued. "I know this will work. I have to do it. And… and… I don't have any money, so I needto borrow some." I thought for a second,did some figuring, then said, "Two hundred dollars ought to do it." Then I shut up.Daddy looked at me for a while. Finally, I saw what I thought was a smilestarting on his face and I thought, everythingis going to be OK. Then he spoke,and I knew I'd been wrong. "Son, I know you think that's the thingto do, but let me assure you, that's the last thing you need to do rightnow. You need to be still, physicallyand mentally. I won't loan you themoney to do anything I know isn't the right thing for you to do…"I don't know if he had anything else tosay or not. I jumped up, ran outside, gotin my car and headed for town. As Idrove, I began thinking, that's OK, I'll come up with the money I need. I'll go back to school, and I'll handle this.To make this part of the story a bitshorter, my good friend, boss, and later my brother-in-law for a while, knew agolden opportunity when he saw one. Minutes after storming out of the house, I sold Joe my custom built skiboat and my full collection of Snap On tools for $120.00. Joe still thinks it was funny, and I stillgrieve for the boat. I knew I was cutting it close toattempt a 1,000 miles (round trip) on $120.00, but a nineteen-year-old on amission can rationalize anything. Before the sun went down, I was heading west on Highway 100. Eight hours and $75.00 later, I was parkedbeside her dorm, which wasn't co-ed, so I huddled in the cold car until shecame out at 8:00 AM. She took one lookat me and shouted, "Bert Carson, I'm done with you. I don't ever want to see you again. Ever!" I was speechless. She spun on her right heel, and resumedwalking to her first class. I watchedfor a moment knowing there was nothing I could do to stop her. I also knew Daddy had been right. Then I thought, if I drive straight homemaybe daddy will never realize I've been gone. As I walked to the car, I mentally counted the money in my pocket anddid some math. I figured if I drove slowand didn't eat anything, I would be able to make it. The last thing in the world that I wanted wasto call daddy and ask him to bail me out.I headed back toward Montgomery. Just south of the city, I had a flattire. There was no money in the budgetfor tire repair, so I put on my spare, which was slightly larger than the otherthree tires. Going down the road, thecar looked like an old hound dog running a bit off center, which, as I thinkabout it, was very appropriate. I conserved gas like I never had beforeor since. Just outside of Lake City,Florida, with a single quarter left in my pocket, and so low on gas the gaugebounced off empty every time I hit a bump, I had my second flat tire.I coasted off the pavement onto thesandy shoulder in the middle of pine forest that seemed to stretch for ever inevery direction. I don't know how long Isat behind the wheel, before I heard a car coming. I stepped out just as a deputy sheriff pulledin behind my obviously disabled vehicle. Before he could say anything, I told him my story… the long sad versionof it, and he listened to every word. When I finished he said, "That's tough. If I had some money I would help you, but Idon't." He thought for a moment while Iwaited. Finally he smiled, and said, "There'sa store down the road a piece. I'll takeyou there. Maybe the owner will help youout."Minutes later he let me out in front ofwhat was obviously the general store for backwoods area. I was a bit hopeful, when I saw the singlegas pump and the weathered Pure Oil – Firebird sign in front and noticed therack of new and used tires beside the building. I took a deep breath, squared my shoulders, and marched into thestore. The owner called out, come onback, I having a bite to eat back here. He didn't miss a bite of his sandwichwhile I talked, trying not to think about how long it had been since I'd lasteaten. I must have talked for fiveminutes, and he hung on every word. Because he listened so intently, I was sure he would help me. I ended with, "and if you'll let me get atire and a tank of gas, I'll come back tonight and pay you."I stopped talking, and he stoppedeating. There was a long moment ofsilence, and then he shook his head, wiped his mouth, and said, "Son, I'd loveto help you, but I have a rule, and it's simple. I don't help anyone with a sad story and nomoney. I just can't afford to."I turned and headed for the door. I had taken five steps, and I remember everyone of them, when he called out, "Wait a minute.."I turned back toward him as he asked, "What'syour name?"I said, "Bert Carson."He was transformed. When he regained a bit of composure, heasked, "Son, why didn't you say that when you walked in?"I managed to ask what difference itwould have made and he said, "It would have made all the difference in theworld. You see, your daddy has calledevery gasoline distributor with stations on the highway between your house andwherever you were going in Alabama. Mydistributor called me this morning. Hegave me your name and he described your car. He told me that if you came in I should give you anything you needed,because it's all paid for. You didn'ttell me your name, and you weren't driving your car, so it took a while tofigure it out. Sorry 'bout that."I got gas, a tire, and breakfast. An hour later I pulled in the driveway, andonce again daddy was just leaving for work. He walked toward the car, as I rolled the window down. This time he grinned before he spoke and thenhe said, "It's good to have you home, son. Looks like you could use a nap."That happened fifty years and lot ofmiles ago. I've been in a many tightsituations since that day, but I've never quit because, thanks to daddy, I'vealways known that someone had my back. My only job was been to keep going the very best that I could, and that'swhat I've done.

Published on February 05, 2012 15:04

No comments have been added yet.