Medieval Marginalia: Creepy Crawlies

Every month or so, I try to take a week to feature some of my favorite medieval marginalia. Marginalia, in its strictest form, refers to the little doodles and asides sketched into the margins of a medieval manuscript. Largely ignored for many years, and often nonsensical, marginalia is gaining attention because it not only shows how those scribe-monks let off steam, but it gives us a peek into what medieval people found humorous (hint: it usually has something to do with butts, things coming out of butts, and things being inserted in butts. So, the next time someone tries to say that the youth of today are vapid and gross, tell them about the medieval butt stuff.)

However, today I don’t want to talk about butts, I want to talk about insects. Insects do make it into medieval marginalia and into the more purposeful illuminations that can be found scrolling around a letter or a page illustration. The British Library’s Medieval Manuscript Blog pointed out that most of the insects found in marginalia were bees, possibly because they were an insect that offered something in return, whereas spiders and ants were just annoying. As you can see, some of these insect illustrations are absolutely stunning and show great attention to detail and a love of nature.

Detail of a folio from a prose treatise on the Seven Vices, with marginal spiders and a praying mantis, Italy (Genoa)

I highly encourage you to visit the British Library’s Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts to take a closer look at these. For more marginalia examples, please visit my marginalia Pinterest board, where I have collected some of my favorites.

[image error]

A six-legged spider and a ten-legged spider. I have made it my life's work to avoid spiders, and so I actually wasn't sure if it was possible for there to be a ten-legged spider…which meant, as a responsible researcher, I had to go look it up, which meant a Google search which meant PICTURES of spiders. AAAACCCKKK!

You’re welcome for doing this for you.

Arachnids have 8 legs. Period. The little devils can lose a leg or two, but they don't grow more than 8 at a time, so either the artists were not very observant or (more likely) they were too busy running away to get a good look at their subjects.

Detail of a miniature of bees guarding their hives against a marauding bear, from Flore de virtu e de costumi (Flowers of Virtue and of Custom), Italy, 2nd quarter of the 15th century

I love this one. The bees are like, "hey bear, how about we kill you and use your fur to insulate our hives? And the bear is like, "No thanks, bees!" Inspiration for the Berenstain Bears, perhaps?

Detail of a miniature of bees collecting nectar and returning to their hive, from a bestiary with theological texts, England, c. 1200 – c. 1210

My father is a beekeeper, which means that I spent my childhood being stung more than the other kids in my neighborhood, and I was forced to learn about the different kinds of hives. These pretty, cloche-shaped, braided hives are called skeps, and they have been around for over a thousand years. Another thing I like about this drawing is the way in which the bees are all traveling in the same pattern. This is something that bees actually do. It was an observant scribe who created this little bit of marginalia. :-)

Detail of a marginal painting of flies surrounding a dog, from the Maastricht Hours, Netherlands (Liège), 1st quarter of the 14th century

This one bothers me because I don't like to see a dog being taunted, and these flies are jerks. What this dog needs is a murderous, medieval rabbit to ride to his rescue on a man-headed snail (see marginalia week, October 2021 on my Instagram).

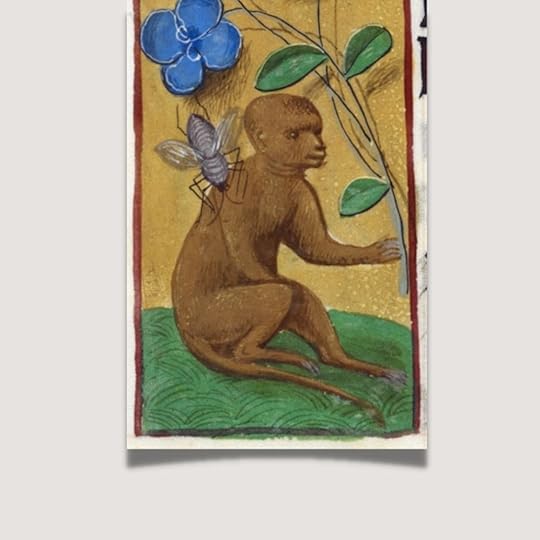

Another example of a fly being an asshole as it antagonizes a monkey. I dislike monkeys, having spent quite a lot of time in their company when I lived in southeast Asia, but this good-natured fellow doesn't deserve a sting.

Miniature of the Patriarch of Antioch being attacked by bees, from William of Tyre’s Histoire d’Outremer, France, 1232-1261

At first glance, it looks like the Patriarch of Antioch is being attacked by bees while his friends stand around and gossip about him. Upon more study, however, we learn that the patriarch of Antioch is tied up (notice the rope around his neck and hands) and he has been smeared in honey and set upon by a swarm in order to execute him. The gentleman in the foreground with upraised finger is Raynald of Châtillon, made infamous to modern audiences in the movie The Kingdom of Heaven. Yes, that Raynald of Châtillon. He was just as bad in real life as in the movie.

Je suis Raynald de Châtillon! Raynald de Châtillon!!!

And on and on. I love this kind of manuscript illustration because it provides me with an assurance that the world today is not terribly different than it was a thousand years ago. Bears still try to get honey and bees sting them. Spiders build webs, and butterflies sip from thistle blossoms. It’s these little bits of shared experience that make the past feel close enough to touch and see. It is evidence that a love of nature and a desire to create beauty is inherent in all of us.

Opinions and commentary are my own. Information about all of these marginalia examples, along with a more educated and less irreverent analysis, can be found in the British Library’s Medieval Manuscript Blog .