The Dying Light – III

After college, I got the engineering job, but soon found I hated everything about working for an energy company in southeast Texas. Houston was a boomtown, a rude awakening of culture shock for a country boy from northcentral Pennsylvania.

It was a new, up-and-coming company, with smart, ambitious people. The main office was in downtown Houston, and it seemed everyone was content to make the long commute from any one of the affluent growing suburbs that surrounded that hot humid city.

I hated Texas. I grew to hate the idea of working for a company that drilled into the ground for oil. Weaning the country off foreign resources be damned. I dreamed of escape, of rolling rural landscapes. Often, I thought of home, of Miller’s Creek, and those wonderful stream-bred brownies that prowled the waters for mayflies.

I was just past my thirtieth birthday, feeling as if life was quickly passing me by when I got the phone call. “Can you come home?”

I knew the news was not good. My mother’s voice sounded weak, resigned.

“Nana isn’t well.”

Nana had fallen … again. This time, she had broken her hip.

It was late May, and the Green Drake Hatch was just starting on Miller’s Creek. Mom and I had just returned home from the hospital to see Nana. Remarkably, she was recovering quite well. There had been no broken hip, just a bad bruise that had left her hobbling. Still, she would need therapy and learn to use a walker.

“How do I tell Nana that it’s best she be put in a home?”

We sat on wooden rocking chairs on the porch facing Miller’s Creek down below. A gentle breeze blew the chimes dangling from a ceiling hook. The wind felt warm, a summer kind of breeze.

“I’m thinking of selling the place,” mom said. “It’s either that or move into town. I just can’t take care of an old woman out here in the country. She needs to be close to medical services.”

“But mom. You love it here.”

“Everything in life has its time,” she said, brushing away a single tear from her cheek. “Maybe it’s time to move on.”

She bit down on her lip and rocked back and forth in the chair. “I have a realtor coming out tomorrow.”

“You’re gonna sell the place?”

I looked to my right at the screen door leading into the kitchen. It whined and closed with a sharp slap when it closed. How many times as a boy had I raced across this porch and gone through that door. The wooden planks of the porch where we sat were chipped and badly in need of paint. Mom’s garden, where she always planted carrots and snapper beans, radishes, tomatoes, and some years even corn, was on the other side of the house next to the old springhouse. Nana always tended to the small spot in the garden where her big plump strawberries grew. The first batch would be just about ready to pick.

“What about your garden? You’ve always loved to garden,” I said hopefully.

“I didn’t plant one this year.”

“What?” I sprang from my chair and loped down the two steps from the porch. Sure enough, weeds and crab grass had invaded the large rectangle annually given over to her bountiful array of vegetables. A crow from the roof of the house squawked at me.

I walked back to the porch. “Geez mom,” I said.

“I’m tired Billy,” she said. “Just plain tired.”

She looked tired. In the long time since I’d been home her hair, which she grew long past her shoulders, had gone almost completely gray. The lines on her face had deepened. She was too quickly becoming an old woman.

I plopped into the rocking chair. For the longest time, the two of us sat there, next to each other, rocking gently, the porch planks creaking, the gentle spring breeze tinkling the chimes.

“Aren’t you going to go fishing tonight?”

“Fishing?” Of course, it had crossed my mind. “I don’t know. I don’t even know if I remember how anymore. It’s been so long time since I picked up a fly rod.”

“Oh honey. It’s like riding a bike. You don’t forget how to do that.”

“True,” I said.

“Isn’t this when those big bugs are out on the water? What do you call them?”

“Green Drakes. Yeah.”

She gave me a funny smile and nodded toward the far end of the porch where my fly rod was leaning in the corner.

“So that’s where it is,” I said.

“What? You thought I got rid of it?”

She got up slowly from the rocking chair. “I’ll whip up a quick supper and then you can fish.”

I looked down the hill where I spotted a single fisherman in a vest and carrying a rod disappear into the rhododendrons along the stream. Trailing behind him was a young boy, perhaps ten or eleven, carrying a little tackle box in one hand, a rod in the other. “Wait up dad,” he called out.

The sun had disappeared behind clouds after supper. A soft rumble of thunder shook the sky as I went down the hill from the house to Miller’s Creek. And then it dawned on me. Would this be the last time I fished here?

My old man said a fisherman should have a plan whenever he went fishing. What flies to use, what parts of the stream to fish.

“Sometimes the riffles are the prime holding spots for the damn trout,” he said. “Don’t forget the edges and along the banks. They don’t always sit waiting for bugs in the deep holes.”

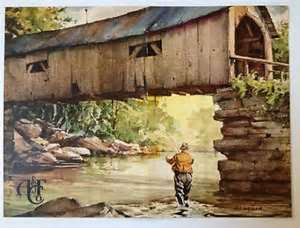

Over the water, mayflies floated, including some Green Drakes. A spinner fall had just started in the early evening, occasional bugs dropping to the water.

At the first bend in the stream, I heard a trout rise for a fly, a soft splashy sound interrupting the quiet of the early evening. Sure enough, a ring appeared on the water’s surface underneath the branches of a pine reaching over the creek.

I felt a stir of excitement. It had been a long time since I’d fished. It was all I could do to keep my hands from shaking as I tied a Green Drake on to my leader when the trout rose once again.

I calculated the distance I needed to cast—about forty feet–from where I stood to the spot of the rise. I pulled some line from the reel and waved the rod back and forth and let loose the line. The fly fell with a smack on the surface along with the trailing leader in a heap, a clumsy cast, sure to scare the trout.

“Jesus. Didn’t I teach you how to cast a better than that?”

It was my old man. There he stood on the bank not far away, wearing that same old floppy fishing hat, a faded olive-green fishing vest, an unlit cigar clenched between his teeth. “Ten o’clock, two o’clock. Remember?”

I remembered. How could I forget? The casting motion. Bring the rod back to the ten o’clock position, then bring it forward to two o’clock for the line to go.

He reached into his vest and pulled out a fly box before poking through the selections. He looked about the air.

“There’s a few Green Drakes out,” he said. “Probably in the next half hour or so is when they’ll really start coming.”

In letters mom wrote to me, in our long-distance phone calls, she had made it clear that my old man was all but out of our lives. She’d even heard a rumor that he was “shacked up with some hussy in upstate New York.”

“Why don’t you just get a divorce?” I asked.

“Your father doesn’t want one,” she said.

“I guess he likes to show up now and then to fish Miller’s Creek.”

“Oh Billy, I don’t remember the last time he’s been home to do that.”

And now, here he was.

Another soft rumble of thunder gently shook the sky. My old man looked skyward. “Jesus, I hope it doesn’t storm. It’s been too long since I fished the Green Drake Hatch here.” He glanced my way before lighting up his stogie. He stared at the water. “Ya probably scared that fish with that horseshit cast,” he said.

“Likely so.”

“What do you say we head downstream a little ways?”

“Sounds good.”

I followed my old man along the well-worn narrow footpath next to the stream. Strange evening calls of birds filled the air as we moved past more rhododendron and brush and negotiated the occasional log blocking the path.

“Let’s try here for a while,” he said.

We were about a hundred feet or so before a swinging bridge over the creek. Just on the other side of the bridge back from the bank was a one-story cabin with a long front porch facing the creek. Near the bank was a fire pit surrounded by a few weathered Adirondack chairs.

My old man had once bragged about catching a dozen trout in just a half hour from this spot. Naturally, I had tried my luck here at different times over the years only to find much less success.

Still, it was a prime spot for holding trout. Just on the other side of the bridge was a big oval-shaped pool, one of the deepest sections of Miller’s Creek. As a kid, I had gone swimming here. By the time I was well into my teens, I reluctantly took part in a few forbidden nights of skinny dipping with some of the local kids. My first summer home from college I lost my virginity here to a girl named Lucy whose family owned one of the cabins downstream.

We made our way around the bridge and down the bank.

Several trout were rising in the slow-moving water of the pool.

My old man took a drag on his cigar and studied the water. “I’ve waited a long time for this.” He smiled and gazed at the water for a few more moments and looked at me. “It’s good to be out here again … after all these years.”

“Good to see you dad.”

“Yeah. Good to see you too junior.”

It was the best evening of fishing I ever had on Miller’s Creek. For the first time in my life I matched my old man fish for fish. After every other cast, it seemed, one of us was reeling in a trout. They were gulping our Green Drakes like hungry men from a Depression food line.

With each hookup, my old man would emit a loud shrill whistle, the same whistle he had used to summon me home as a kid.

As it grew dark, the trout continued swallowing our Green Drake offerings.

“This is almost becoming monotonous,” my old man said. With a sigh, he reeled in his line and set down his rod. He reached into one of his vest pockets and pulled out a flask. Uncapping it, he took a long pull on it before offering it to me.

I took a drink. I was barely a drinker, and the whiskey tasted bitter.

“I think I’ve had enough fishing for one night,” he said. “How about you?”

I shrugged. “Probably so.”

I handed him back the flask.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him staring at me as he took another drink.

“Same ol’ Billy. Take things as they come.”

I bristled at his words. I was always too laid-back, too easygoing for him. He’d wanted me to join him as a salesman instead of going off to college. It was the only way to make a living, he said. A man was on the road, not in an office, making his own rules, living by his wits and his own assertiveness.

“It’s gotten me this far,” I said.

“Yeah … yeah I guess you’re doing okay. Financially anyway. Your mother says you don’t like your job.”

He was still studying me as we stood there next to the creek, waiting for some response.

“It’s got its ups and downs.”

Without looking at him, I raised the rod up and made another cast. In the waning light I could barely see my fly floating on the surface.

I jerked back the rod a split second after the splash. The weight on the line was unmistakable. I could feel the fish plunge for the depths. I held the rod high as he leaped four feet from the water.

“Hell junior.”

The trout tried desperately to shake the fly and then he was zigzagging in the water. I let him run before bringing in line. The fish made another run and one more heroic leap before tiring. The line was tight as I brought him toward me.

The trout turned out to be the biggest fish either of us caught that evening—more than twenty inches long with a thick girth.

The two of us went to our knees to study my trophy, one of the mammoth stream-bred brownies of Miller’s Creek.

“I say we keep this lunker,” my old man said. “He’s a meal.”

“Mom can pan fry him in cornmeal,” I said.

“I got a better idea,” he said. He was looking across the creek at the cabin.

I didn’t know what he was talking about, but I didn’t like the gleam in his eyes.

“Yeah. I guess I can throw him back. I don’t like to eat trout that much anyway.”

“That’s because you haven’t had ‘em cooked over a fire streamside.” He was still staring across the creek toward the cabin.

“C’mon,” he said. “Let’s cross.”

“Dad. That’s not our property.”

The no trespassing signs were posted on trees on the other side of the creek.

He was already several steps into the water and looking back over his shoulder at me. “Are you coming or what?”

“Jesus dad. Would you grow up?”

“C’mon junior. We don’t have all night.”

I watched him slosh through the shallow, far end of the pool and climb up the bank on the opposite side.

He was already gathering some twigs for the fire when I cursed to myself and crossed the creek with the dying trout cradled in my arms.

In no time at all, my old man had a nice twig fire going in that fire pit.

“What if the people who own this cabin suddenly show up,” I said nervously. “I mean … we’re trespassing you know.”

“Fuck ‘em. Besides, that isn’t likely to happen.”

“So. You know the people who own it?” I peered through the darkness at the cabin. It was a rustic old place, for sure, not much more than a hut really. Firewood was stacked on the porch. I was relieved no vehicles were parked in the dirt driveway next to the cabin.

“Bill Hunley owned it years ago, but hell … he’s been dead a long time. I don’t know who has it anymore.”

He was huddled over the small fire, building a little wall of rocks around the flames. All at once, he stood up and admired his work. “Now. Let’s get that fish cleaned and have ourselves a trout supper.”

I stared at him.

“You want me to clean the damn fish,” he said.

“Have at it.”

“Where is it?”

“Soaking in the stream.”

“Well go get it.”

He was making me feel like his little boy all over again, carrying out his orders. At work, back in Texas, a supervisor often made me feel the same way.

“I’ll grab some of that firewood,” he said, looking toward the cabin. “We’ll cook that fish and have ourselves a real fire.”

I watched my old man deftly slice the trout’s belly with a knife and scrub out the entrails before cutting off the head and the tail.

“You really plan to eat this fish?”

He smiled and poked at the flames. He looked back at the cabin. “I’ll bet there are some plates and utensils in there. Hell. Maybe even a nice frying pan.”

“Dad. No.”

And then, he was walking toward the cabin and up the porch steps.

“That’s your father,” Nana said more than once. “Does what he wants and when he wants. Got no check on his desires and appetites.”

This had come right after my old man had found himself in a bad spot with the law. The details were fuzzy, but it had something to do with a kind of minor embezzlement involving a sales client.

“I guess that’s part of his charm. Huh Marie?”

“I guess,” my mother said, poking at her meal.

And now, all these years later, I could see that my old man really had not changed as I watched him try to jimmy the door of the cabin.

“Dad. Not a good idea.”

My old man let out a whistle. “Well what do you know,” he said. “The door’s open.”

His dark figure disappeared into the cabin, and in the next moment light filled the inside of the building.

“We’re in luck,” he called out before emitting another whistle. “Plates, forks and knives, a frying pan, and even some grub.”

A horrible feeling of anxiety washed over me.

“Look at this junior,” he said coming back to the fire. “They had steaks stored away in a freezer.” He set the steaks on the ground and quickly unwrapped the aluminum foil covering the meat.

“For God’s sake dad. Put ‘em back. Really. This is crazy.”

“Hell junior. Finders keepers.”

I just looked at him.

His face was lit up from the flames, displaying the sheer delightful mischief of a teenage boy who’d just gotten away with shoplifting merchandise from a store.

The smell of fish sizzling in the pan over the flames filled the night air.

“You’re like a fucking kid,” I said.

My old man’s wicked smile quickly vanished.

“What the hell is wrong with you?” he said, turning angry eyes on me.

“What is wrong with me? What is wrong with you? Trespassing, breaking into a cabin, stealing.”

He continued staring at me. With a sigh, he looked down at the steaks unwrapped from the foil. “You want me to return them? Okay. Ya little pussy. I’ll return them.”

“I think that would be a good idea.”

“But I’m eating off these plates.” He shot me a sneer. “Okay?”

“Sure. Have it your way,” I said.

Eating that trout along the banks of Miller’s Creek on that May evening next to that small campfire felt deliciously forbidden. In a weird, twisted way, we were bonding. There was no denying it.

“Pretty tasty trout. Eh junior?”

“Not bad. Not bad at all.”

“Fresh from the stream cooked over a fire. Best way to eat trout.”

I saw the flash before my old man, a flickering and bobbing of light from upstream.

“Oh shit,” I said. “Now we’re in trouble.”

My old man had just pushed a forkful of meat into his mouth when he noticed the light. “Bullshit,” he said. He reached into his vest and pulled out a Glock. In the next motion, he snapped in the magazine before getting into a crouch and holding the gun with two hands. He looked more than eager to have an excuse to use it.

God no, I thought.

We remained there next to the campfire watching the light draw nearer, bouncing along the path beside the stream. My old man had the gun trained on the light.

“Hey you two.”

It was the voice of a woman.

“Identify yourself,” my old man called out. He held the Glock in one hand with the barrel pointed toward the dark figure.

“It’s me.”

“Mom?”

“Nana’s dead.”

“What?”

My old man lowered the gun. “Took the ol’ coot long enough,” he said, but not loud enough for mom to hear. Mom stood on the other side of the stream, holding the flashlight. I could just make out her dark figure.

“Why don’t you two come home?”

“You okay Marie?” my old man said.

“Just come home,” she said before retreating down the path.

“Wait up mom. We’ll walk with you.”

“Put out that damn fire first,” mom said. “What are you two doing on private land anyway?”

From the book, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. His author page can be found at https://www.amazon.com/Mike-Reuther/e/B009M5GVUW%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_scns_share