Who is the Real Sherlock Holmes: 5 Possible Answers

Sherlock Holmes has delighted and amazed reading and viewing audiences for over a hundred years. It’s no wonder that a character vivid for his faults and eccentricities as much as his triumphs feels real in a way that many less-impactful characters do not. Fictional as he may be, pieces of Holmes are found in the real lives of several notable people, and even his large-than-life deductions originate in reality. The following list contains detectives and authors, doctors and even a criminal. The ways these men relate to Holmes may not be obvious at first, but each man warrants the title in some way. Let’s explore their lives and their connections to the world’s greatest fictional detective.

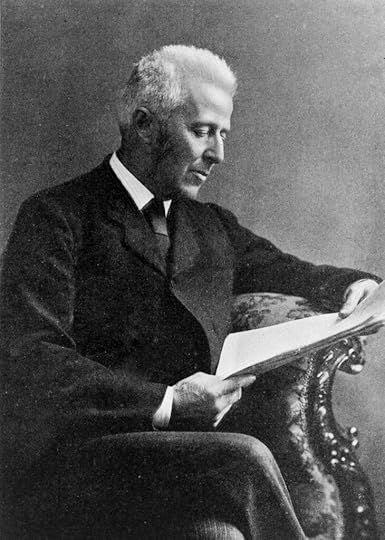

Dr. Joseph Bell

Any discussion of a real-life Sherlock Holmes is likely to involve Scottish surgeon and teacher Joseph Bell. Bell was born in 1837, the descendant of Benjamin Bell, the first scientific surgeon in Scottish history. In his own right, Bell became a renowned physician and lecturer, who notably used deductive reasoning to diagnose patients. Bell’s connection to Doyle is direct. The two worked together at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and Doyle became Bell’s student. Obviously, the young Doyle would have had many opportunities to observe Bell’s methods and habits. Even more notably, Bell used his abilities to assist the Scottish police and reportedly even consulted on the case of Jack the Ripper, alongside forensic expert Henry Littlejohn. It’s not difficult to see the inspiration for Holmes here, and even, perhaps, for his partnership with John Watson. Bell was aware of the inspiration and was complimentary of Doyle as Doyle was of him.

Sir Arthur Conan DoyleDoyle is an often-overlooked answer to the quest of finding the real Holmes. One reason is how enjoyable many people find playing The Game (treating Holmes as a real person and figure in history). Nevertheless, the truth is that there’s a mind behind the genius, and it belonged to the brilliant author.

Twice-married father of five Doyle clearly did not share his creation’s lifestyle, but he did engage in more of Holmes’s behavior than the average person may realize. Julian Barnes’s celebrated historical novel Arthur and George explores Doyle’s involvement in the George Edalji case, in which a young man of color was falsely accused of animal mutilation. Doyle’s work combined two elements also found in his writing: detection and social justice. His painstaking examination of the evidence is certainly reminiscent of Holmes, as is his indignation at the injustice. “The Yellow Face,” one of the more problematic Holmes stories by modern standards is, at the same time, one of the most forward-looking for its time. In the story, Holmes fails to solve his case but presides over a touching scene of acceptance for the child of an interracial couple. Doyle’s viewpoints can’t be separated from his work, and Edalji wasn’t his only cause.

The most direct support for Doyle as the real Holmes is the painfully obvious fact that somebody had to come up with the intricate plots and deductions that fill the pages of his best stories. In many cases, Doyle was incredibly prescient in Holmes’s use of forensic technology that police would later adopt as standard practice. He may not be the most outlandish or glamorous option for the real Holmes, but he’s quite possibly the most accurate.

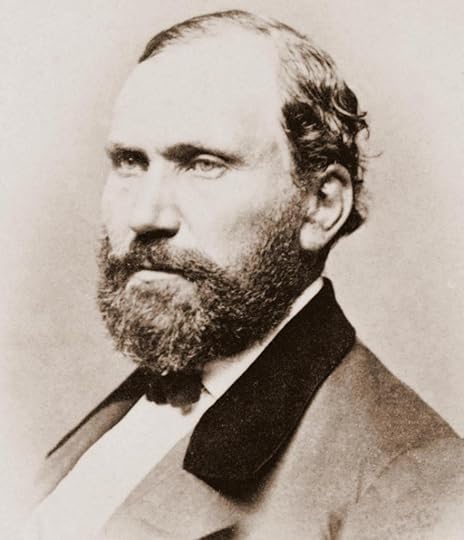

Allan Pinkerton

Pinkerton, famed establisher of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, is one of the more unexpected people on this list, but he’s an obvious choice, though a lot of people miss his connection if their enjoyment of Holmes is restricted to Doyle’s short stories. Doyle’s final Holmes novel, The Valley of Fear, includes a character based on real-life Pinkerton detective James McParland and his exploits while infiltrating the Molly Maguires. Why, then, is Pinkerton on this list instead of McParland himself?

To understand this, we have to look back. In 1877, Pinkerton published his account of his agency’s successful infiltration of the Molly Maguires in his work titled The Maguires and the Detectives. This was long before the publication of The Valley of Fear, which was serialized in 1914-15. Between these events, Doyle met Allan Pinkerton’s son William, who told him of MacParland’s exploits and the case. Taken with the account, Doyle fictionalized it and published his final Holmes novel.

Certainly, the Pinkertons and their exploits fascinated Doyle, and his choice to specifically reference them codified this fascination into inspiration. Allan Pinkerton makes this list because he, rather than McParland or his son William, was the originator of the Pinkertons, designer of their operations, and literary chronicler of the McParland operation. It’s no leap to assume that William’s account to Doyle was based on his father’s.

Admittedly, it’s hard to argue that Pinkerton himself is found anywhere in the character of Holmes, but as a contemporary who inspired Holmes’s author, he gets a mention here as a real-life detective who operated using forward-thinking methods and operations that were similar to those Doyle wrote about. He’s a historical person we can look to for greater understanding of how a Sherlock Holmes-like figure once operated in the real world.

Eugéne Francois VidocqIt would be a crime (har har) to leave off this list the man known as “the father of modern criminal investigation.” Vidocq’s life is a fascinating tale, and it’s tempting to get lost in the weeds of his criminal-turned-law-enforcement exploits. For our purposes, a few key points stand out.

A criminal from his teens, Vidocq built a reputation as a clever and ingenious escape artist, with exploits that sound like something from a dime novel. Nevertheless, in his 30s, Vidocq made a bargain with frustrated law enforcement–he turned informant. Vidocq, at this point, became the first real-life consulting detective, a title later assumed by Holmes. In 1811, Vidocq formed the organization that would soon became France’s Sûreté Nationale. Following this, he formed his own private agency of detectives.

Vidocq was a major inspiration for Émile Gaboriau’s Lecocq, the popular fictional detective to whom Holmes refers in A Study in Scarlet, calling him “a miserable bungler.” Doyle’s mention of the character indicates his awareness of Lecocq’s relevance.

Vidocq lived out a larger-than-life existence that rivals Holmes’s adventures for lurid excitement and twists and turns that would seem outlandish in fiction. As the basis for a rival fictional detective and because of his own life’s exploits, Vidocq becomes a contender for the real Holmes title.

Dashiell HammettA contemporary of Doyle’s later life, Hammett is arguably the successor to Doyle, and his detective characters are direct successors to Holmes. Hammett was born in 1894, when Doyle was already a grown man, and his writing style differed sharply from Doyle’s.

As a former Pinkerton detective who mined his own experiences heavily in his writing, Hammett relates specifically to two stories by Doyle: “The Lion’s Mane” and “The Blanched Soldier.” These stories are, of course, notable because they are narrated by Holmes himself, a major departure from Doyle’s usual practice of using Watson as the Boswell-like chronicler of Holmes’s exploits. Similarly, Hammett departed from the earlier practice of third-person narration and used first person in his early breakout stories, a style that would come to dominate the mystery genre and proliferate after him.

Hammett’s early style was a departure from the idea of the gentleman detective. His characters are sharp, unvarnished, and in-your-face, and his narratives can be quite direct and brutal. He also incorporated humor liberally.

As a literary titan with a detective past, Hammett’s life combined the life of Holmes with the life of Watson, his chronicler. His Continental Op character, who revolutionized the genre, serves as the first-person narrator and observer of his own experiences. In his book The Lost Detective, biographer Nathan Ward posits that the Op is an autobiographical insert of Hammett himself, using his Pinkerton exploits and the style of writing Pinkertons were taught to employ in their reports to craft a new kind of detective and detective story.

A look at Hammett’s classic The Thin Man finds his wisecracking detective marrying into money and solving a twisted case using detection methods that would be completely at home in a Holmes story. The hard-boiled, direct style remains, but the character of Nick Charles, a charming eccentric with plenty of money and a lavish lifestyle, circles back to the rarified air of the gentleman detective–the company of Holmes, Lecocq, and Poirot. Hammett ultimately fused the old with the new, to great success and acclaim.

In the end, Hammett’s real life contained elements of Watson, Holmes, and Doyle, as he perfected the detective-as-narrator and advanced the genre, while looking back to his early adulthood work as a Pinkerton and occasionally dabbling back into the world of the eccentric gentleman detective.

ConclusionThere’s no single, perfect answer to the question of who the real Sherlock Holmes actually is. Several people who lived during Doyle’s time fit the bill in some way, and Doyle himself is a strong contender. Ultimately, a large part of the legacy of Holmes comes from his uniqueness. Most readers may not be able to relate to his intellect, but we can certainly relate to his weaknesses and failures. Unlike flat, boring characters, Holmes is multi-dimensional enough to feel like a real person, to the point that many of us find ourselves wishing he was and imagining he might be–over and over, reinventing the specifics of his life to fit our times and our contexts through adaptations.

The quest for the real Holmes is ultimately a personal one, dependent on the parameters placed around the question. Is it the man who wrote Holmes, who painstakingly crafted plots and chains of reasoning that are still admired today? Is it more likely a Pinkerton or a Vidocq, men whose actual lives mirrored elements of Holmes’s life? Is it the doctor who supplied Holmes’s most notable trait, his nearly-superpowered observational skills? Or is it Hammett, who united the literary with the real-life practice of detection in a way that had not been seen before? The answer is in your hands.

Maybe you think the real Sherlock Holmes is someone else entirely. There’s no right or wrong answer. The enduring presence of Holmes, our tendency to see him anywhere we look, speaks to how influential and timeless the character continues to be. And he’s not going anywhere.

Learn more about my novels of Sherlock Holmes.