Valentine’s Day

For Valentine’s Day this year, Americans are expected to spend about 22 billion dollars on gifts for romantic partners, family members, friends, and pets. The most popular gifts for the day are chocolates (not for the pets), flowers (particularly red roses), jewelry, fine dining, and greeting cards.

The interesting 3-D card shown on the left includes most of the traditional symbols: the predominantly red color, the heart symbol, the word “valentine,” a suggestion of lace, and red flowers. We’re missing Cupid, but he shows up in lots of silhouettes, and he’s a major player in older valentines, like the one shown. So are white doves and swans.

While all of these elements are widely accepted today, their history isn’t exactly what we were told.

Saint Valentine

It’s called Saint Valentine’s Day, but it’s not clear why. There are dozens of saints named Valentine in the Catholic Church pantheon, but they weren’t patrons of love. One or perhaps two might have been decapitated on February 14, 269 or 270 CE during the Roman persecution of Christians. We get this information from a history of saints written over 1300 years after the fact by a Jesuit scholar named Jean Bolland in 1643.

According to Bolland, one of those beheaded was Valentinus, whose skull was whisked away after his death and broken into pieces, each of which was said to have curative powers. Churches in Madrid, Dublin, Prague, Malta, Glasgow, and Lesbos all claimed to have bits of it. One bishop said he put out a forest fire and cured demonic possession with a fragment of the skull.

However, the tales of Saint Valentine carrying notes between lovers jailed by the Emperor seem to be popular Medieval tales without much basis in history, even Bolland’s.

Lupercalia

If Valentine’s Day didn’t start with Saint Valentine, where did it come from? The most likely candidate is an ancient Roman festival called dies Februatus, which is supposed to have come from the earlier Greek festival of Pan/Lupercus, a goat/man or wolf/man hybrid which had its own priesthood, known as the Brothers of the Wolf (Luperci). Each year, in the Lupercal Cave, the priests would sacrifice one or more goats. After the feast that followed, the Luperci cut off strips of goat skin. Then, according to Plutarch, “many of the noble youths and magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery and the barren to pregnancy.”

The festival was already a regular feature of the Roman calendar by the time Julius Caesar used the occasion to refuse a golden crown in 44 BC.

Of course, many refuse to admit any connection between Lupercalia and Valentine’s Day. But there is one clear link. In the etching showing the lads enjoying smacking the ladies with shaggy strips of goatskin, there’s a familiar figure: Cupid.

Cupid

In typical Valentine’s day graphics, Cupid is shown as a winged baby boy who carries a bow and arrow. He’s often described as cherubic. He has wings, true, but he’s no angel.

In Greek mythology, Eros (known to the Romans as Cupid) was the son of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. Her symbols were doves, roses, swans, apples, and pomegranates, as well as the color red. Perhaps the cards should read “Happy Aphrodite’s Day.”

According to some sources, Cupid’s father was Mars, the god of war, which would make Cupid the offspring of love and war. Originally he was depicted as a handsome young man who had the power to make people fall in love, even against their will. He was depicted on vases as far back as 900 BCE, a representation of passionate, irrational desire. In 500 BCE, Euripides described Cupid as able to arouse love “with murderous intent, in rhythms measureless and wild.”

He carried two kinds of arrows: gold-tipped arrows that aroused desire and lead-tipped arrows that aroused hate.

The statue of the young man Eros/Cupid in Piccadilly Square, London, is shown on the left.

The Romans, uncomfortable with the Greek version of Eros, changed him into a winged boy who did the bidding of his mother, the goddess of love. And that’s the figure that painters included in their works when all things related to ancient Greece and Rome became fashionable once again during the Renaissance. Petrazzi Adolpho painted the slightly younger version of Cupid in “Eros Triumphant” (center). In later paintings, he becomes younger still, until he’s hardly a toddler, like the baby boys in “Les Amours des Dieux” by Francois Bouché (right). In these paintings, Cupid carries his bow to shoot arrows of love. Because he’s young and small, he’s cute rather than threatening.

The Heart Symbol

Cupid fires his arrows into a heart, arousing desire. But up until the 15th century in the Middle East and Europe, the liver was considered the seat of all emotions and the origin of the body’s blood, not the heart. When you look at it, though, the design on the valentines doesn’t look much like a liver or a heart. So where did the idea come from?

Images like the heart symbol appear on ancient pottery from the Mediterranean regions, but they represent ivy, grape, or fig leaves, not a heart.

A clear heart-shaped symbol appears on a coin (shown, below) from ancient Cyrene in North Africa (300 BCE), depicting a silphium seed. Silphium was used as a seasoning, perfume, aphrodisiac, and medicine, especially as a form of birth control. It was known to ancient Egyptians and popular among many Mediterranean cultures. Romans said it was worth its weight in silver coins. Once a major trade item, unfortunately it fell victim to over-harvesting and climate change.

In 1250, a French love poem described two lovers peeling a pear with their teeth. In the illustration, the man hands his “heart” to the woman. It’s pear-shaped. Though some sources claim this is the first instance of the heart symbol, it still looks like a pear to me.

The best guess seems to be that our modern heart graphic came from playing cards.

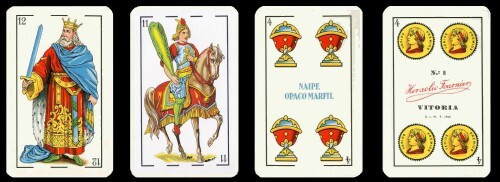

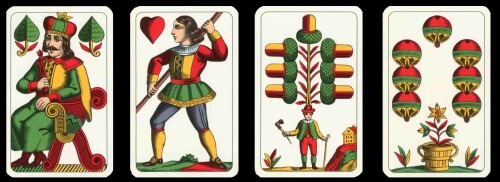

Gaming cards emerged in China in the 10th century. Through trade networks, the idea spread to India and Egypt in the 1300s. They replaced the Chinese numeric system with four suits: cups, coins, swords, and polo sticks.

From there it spread across the Mediterranean and into Europe, where the suits’ names were influenced by those in tarot cards: swords, clubs, cups, and coins (shown above left).

Each area adopted their own names. The Germans and French turned the cups/chalices suit into the heart symbol we’re familiar with today.

By the 1500s, the heart symbol was popular throughout Europe, frequently used in reference to courtly love.

Chocolate

And in that heart-shaped box we have – chocolate. Cacao was considered a food of the gods by the Mesoamericans who blended the ground seeds with hot chilies and drank the bitter, frothy mixture.

After sugar became widely available in Europe, the product of enslaved workers on sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean, Swiss confectioners mixed sugar, ground cacao seeds, and milk to create milk chocolate. At first it was reserved for the very rich, but soon its popularity spread. It was considered a taste delight and an aphrodisiac.

Cupid reappears here, linked to chocolate by the genius of Richard Cadbury, who was looking for new ways to use cocoa butter. In 1861, he came up with “eating chocolates,” which he packaged in beautiful heart-shaped boxes decorated with Cupids and rosebuds. Soon Milton Hershey and Russell Stover followed suit. Stover’s most popular was the Secret Lace Heart, assorted chocolates in a box covered in satin and black lace.

Changes

All those elements – the chocolates in the heart-shaped box, the lace and jewelry and red roses and promises of sex – are part of the Valentine’s Day experience we’ve come to expect from advertisers. But its very narrow focus makes some people hate the holiday. Some say it only makes those without romantic partners or those in bad relationships feel worse. Some say they feel forced to buy expensive gifts or put up with crowded restaurants just to prove they care. Some say no matter what they do it won’t live up to the hype.

Perhaps the holiday needs an update. From the selection of valentines I saw, the focus now seems much broader than just romance. The cards celebrated a range of loved ones – relatives, friends, teachers, kids, even pets. One I found says “Happy Hearts Day” on the front. Inside, it says, “Today is for thinking about the people who make a difference in our lives, the ones we want the best for and care about, no matter what. That’s why I’m thinking about you today.” It’s unrelated to the usual complications of Valentine’s Day. It’s just a lovely sentiment.

Another one I like featured a smiley face on the front, with the words, “You’re a nice human.” Inside it says, “Thanks for always being you! Happy Valentine’s Day.” Now there’s an uncomplicated compliment.

Happy Valentine’s Day – or Aphrodite’s Day – however you choose to mark it!

Sources and interesting reading:

“Aphrodite,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphrodite#Genealogy

Henderson, Amy, “Chocolate and Valentine’s Day Mated for Life,” Smithsonian Magazine, 12 February 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-chocolate-and-valentines-day-mated-life-180954228/

Bitel, Lisa, “The Gory Origins of Valentine’s Day,” Smithsonian Magazine, 14 February 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gory-origins-valentines-day-180968156/utm

Valentines from American Greetings, which I bought, include the first one pictured and the last two mentioned, American Greetings, Cleveland, Ohio.

Combs, Sydney, “Valentine’s Day wasn’t always about love,” National Geographic, 5 February 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.co/culture/article/saint-st-valentines-day

Crockett, Zachary, “Why is heart emoji so anatomically incorrect?” Priceonomics.com, https://priceonomics.com/why-is-the-heart-emoji-so-anatomically-incorrect/

Dempsey, Bobbi, “Why is Cupid the Symbol of Valentine’s Day?” RD.com, 15 January 2022, https://www.rd.com/article/why-is-cupid-the-symbol-of-valentines-day/

Engel, Steve, “Sex. Lies, and Valentines,” The Crimson, 14 February 1996, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1996/2/14/sex-lies-and-valentine-phappy-or/

Greenspan, Rachel, “Cherubic Cupid Is Everywhere on Valentine’s Day. Here’s Why That Famous Embodiment of Desire Is a Child,” Time Magazine, 13 February 2019, https://time.com/5516579/history-cupid-valentines-day/

“Lupercalia,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lupercalia

McNair, Kamaron, “Americans plan to spend nearly $26 billion this Valentine’s Day – here’s what they’re buying,” CNBC.com, 29 January 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/29/americans-plan-to-spend-nearly-26-billion-this-valentines-day.html

“Playing Card Facts & Trivia,” The Playing Card Factory, https://theplayingcardfactory.com/history

“Silphium,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silphium

Thalhammer, Nick, “The Real Story of Cupid (and other Valentine’s Day Traditions) Cincinnatus Insurance LLC, https://www.cincinnatusinsurance.com/real-story-cupid-valentines-day-traditions/

“Who is Cupid & How Did He Evolve Into Our Modern Valentine’s Day Cupid,” Always the Holidays, 4 February 2022, https://alwyastheholidays.com/who-is-cupid-valentines-sday-cupid/

Yalom, Marilyn, :How did the human heart become associated with love? And how did it turn into the shape we know today?” Ideas, TED.com, https://ideas.ted.com/how-did-the-human-heart-become-associated-with -love-and-how-did-it-turn-into-the-shape-we-know-today/