“There are no slaves in England.” American perspectives. Race and Regency #2

Sarah Baartman was held on display in London in 1810.

Sarah Baartman was held on display in London in 1810.One year before Jane Austen’s beloved novel, Sense and Sensibility, was published, three years after Britain abolished the trading of slaves, and thirty-eight years after the Mansfield judgment, Sarah Baartman was being held on display in London for the amusement of paying-customers who were allowed to poke and prod at her naked body.

The men who did this to Baartman claimed she was there of her own free will; historians think otherwise. It’s 1810, the age of consent is twelve, the last public beheading won’t happen for another ten years and Sarah Baartman is sexually assaulted in humiliating circumstances, daily, for the amusement of bored Londoners.

Here we have some details that add to our picture of Regency England. American chemist, Benjamin Silliman, offers another glimpse into life for Black (and South Asian) Britons in his 1810 book, A Journal of Travels in England, Holland and Scotland 1805–1806.

Benjamin Silliman in 1825.

Benjamin Silliman in 1825.When Silliman did a tour of Britain, he was surprised that Black and Asian people existed in society in much the same way as their White countryfolk. I rather wish he’d written more on his observations in this area, but, as it’s not a long excerpt, I shall give you all that Silliman said on the topic:

“ANGLO ASIATICS AND AFRICANS.

From the rag fair we went on board an American ship lying in the London docks. There we saw several children which have been sent, by the way of America, from India to England, to receive an education. They are the descendants of European fathers and of Bengalee mothers, and are of course the medium between the two, in colour, features and form.

I mention this circumstance because the fact has become extremely common. You will occasionally meet in the streets of London genteel young ladies, born in England, walking with their half-brothers, or more commonly with their nephews, born in India, who possess, in a very strong degree, the black hair, small features, delicate form, and brown complexion of the native Hindus.

These young men are received into society and take the rank of their fathers. I confess the fact struck me rather unpleasantly. It would seem that the prejudice against colour is less strong in England than in America; for, the few negroes found in this country, are in a condition much superior to that of their countrymen any where else.

A black footman is considered as a great acquisition, and consequently, negro servants are sought for and caressed. An ill dressed or starving negro is never seen in England, and in some instances even alliances are

formed between them and white girls of the lower orders of society.

A few days since I met in Oxford-street a well dressed white girl who was of a ruddy complexion, and even handsome, walking arm in arm, and conversing very sociably, with a negro man, who was as well dressed as she, and so black that his skin had a kind of ebony lustre.

As there are no slaves in England, perhaps the English have not learned to regard negroes as a degraded class of men, as we do in the United States, where we have never seen them in any other condition.”

Silliman was a teenager during these travels — though an adult when he wrote about them — and the culture shock is apparent. Without knowing more about his early views on slavery, it’s hard for me to exactly determine if Silliman is impressed or appalled by the relative equality possible for Black and Asian people in British society. What are your thoughts on his remarks?

Relative equality was possible, and — as shown in Silliman’s observations — it would not have been uncommon to see well-dressed Black and Asian Britons walking down the street arm-in-arm with similarly well-dressed White friends, family members or lovers in London.

We discussed last week that, throughout the long-eighteenth century, there was a growing trend of interracial marriages; this was purposely and consciously thought of as a singularly working-class activity. Thus, as Silliman points out, it was quite acceptable for Black men to form romantic relationships with White women of a lower social class than their own.

We might also assume it was acceptable for White men to form relationships with Black women of a lower social class. It was significantly harder for women to marry someone considered beneath their status without long-lasting social consequences; whatever their beau’s ethnicity might be.

It is important to note that when we discuss the social stigma of interracial marriage we are mostly referring to a specifically anti-Black and anti-African stigma.

Silliman reminds us that it was not uncommon for a White man of any rank in society to marry a South Asian woman.

With my own father being half-Indian, I found the comments about children of Bengali mothers and White fathers being accepted into any and all ranks of society particularly interesting. One can begin to imagine a truly diverse picture of the people walking the London streets in the Regency Era. When we imagine Mr Darcy and Mr Bingley taking a morning stroll in town, perhaps now we see the sketch of the world around them more clearly.

Another traveller to England, Samuel Ringgold Ward — though visiting in 1853 — offers us a Black perspective on this relative equality to be found in Britain.

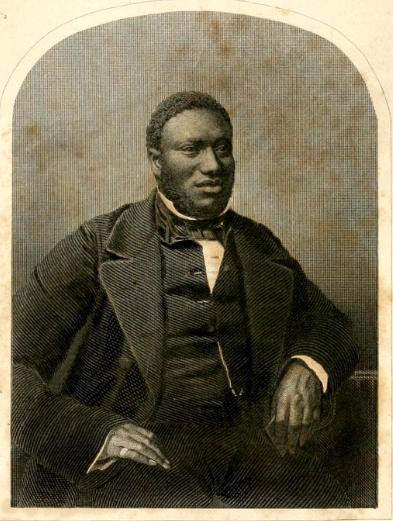

Samuel Ringgold Ward

Samuel Ringgold WardWard has a lot to say about his experience in Britain, all detailed in his 1855 autobiography, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-slavery Labours in the United States, Canada & England. Below are some excerpts:

“It should be, in America and in the colonies, regarded as a matter of importance, for a man wishing to improve both his head and his heart, to visit England. There is so much to be learned here, civilization being at its very summit.”

“Nor, I hope, shall I be considered wanting in gratitude…if I do not mention the name of every town in which I received kindness, and every family and every individual to whom I am indebted. The reason why I shall not do so is simply this: this book must have an end.”

Ward had a very pleasant time visiting England, and mentions his regret that he could not be treated with such equality and friendliness in the country of his birth. It is notable that Ward experiences this not just in London and other big cities, but other smaller towns in England too.

Sir Samuel Cunard — father of the modern cruise ship.

Sir Samuel Cunard — father of the modern cruise ship.It was on his journey to England that Ward reflects on something indicative of that relative equality we were mentioning earlier.

Though Ward’s ticket entitled him to the best of treatment, he was asked by Mr Cunard not to sit in the best dining room because of complaints from American travellers. Otherwise, Ward’s comfort was attended to (author of, Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray kept him company onboard). Mr Cunard’s explanation seemed to be that, while he personally hated racism, business is business. The comfort of White Americans was worth more to him than his personal convictions of equality.

This was something Ward recognised in the culture of British businessmen: they might, at one level, view him as an equal, but they did not believe Ward or other Black consumers had rights equal to their White customers. When it came down to it, money, and not morality, was the motivator.

That’s it for our exploration of Race and Regency today. See you next time!

[image error]