The Headless Horseman of Stones River

Most everyone is familiar with the tale of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow, but in Tennessee we have another headless rider, from the time of the Civil War; the Headless Horseman of Stones River!

LONG SHADOWS: MORE GHOSTS & HAUNTS OF THE CIVIL WAR

Most everyone is familiar with the tale of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow, but in Tennessee we have another headless rider, from the time of the Civil War; the Headless Horseman of Stones River!

LONG SHADOWS: MORE GHOSTS & HAUNTS OF THE CIVIL WAR

Most every schoolchild has at one time or another read the famous legend of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow. American author Washington Irving had quite a knack for turning local gossip and tall tales about the Hudson Valley and surrounding mountains into compelling short stories of the strange and supernatural.

As a boy I remember hearing the thunder booming through the valleys and peaks of the Catskills and you could swear the old stories were true–that it was the sound of Hendrick Hudson’s raucous, curséd, crew, playing rounds of Nine-Pins and quaffing pints of nut-brown ale through to eternity. Likewise, in my youth, I remember being shown the old, twisted oak, where in olden day they had hanged Major André, the dapper English spy, which folks swear is still haunted by the unlucky gentleman ghost. Or say, hearing from Pop Gus, my railroad engineer grandfather, the tale of the Lincoln Ghost Train, (Chapter 32 of Ghosts & Haunts of the Civil War) which he swore he saw one misty April morn as it wound its way from Washington, DC, through the twisty old mountain rail-lines to points westward, on its eternal way, winding back to Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois.

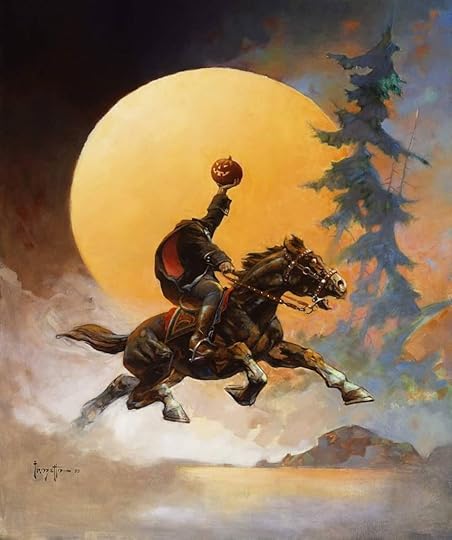

But of course, the ghost tale of the Hudson Valley that topped all others was the aforementioned story by Irving about the headless Revolutionary War soldier. For better effect, I suppose, Washington made the soldier a horseman, although the ghost story as it was originally told was about a Headless Hessian, a green-coat foot-soldier adorned with brass mitre cap. In a forgotten battle against Washington’s men, a solid round-shot of black iron, you see, passed so neatly between his neck and the tall grenadier cap he wore, that it left but a gap of gory goo where once his head had sat.

Some say Washinton Irving’s change to branch of service was an honest mistake, since Loyalist Tory cavalry serving with the Brits wore short green jackets similar in color to some German foot soldiers. Regardless, he was correct about the war and the color of jacket the ghost wore, and of his frightening aspect as well. However, we’re not here to re-tell an old Yankee tale about the Revolutionary War, but to recount the story of a Headless Horseman of the Civil War, whose body was laid to rest without its usual upper appendage in the green fields of Tennessee.

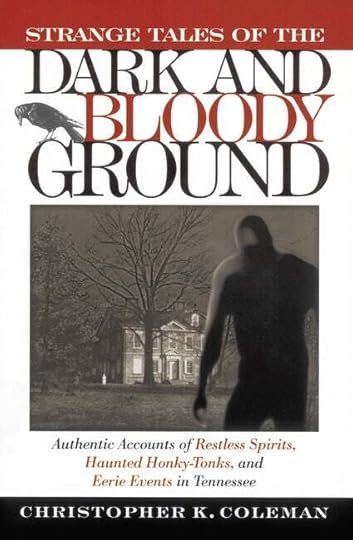

In Strange Tales of the Dark and Bloody Ground, I previously explored the ghosts and haunts of the Stones River battleground, which are as numerous as they are uncanny. There are many other Civil War spirits that haunt the area too, since the National Park only covers a fraction of the original field where they battled, been fatally wounded, and bled until dead. In going over numerous first-hand encounters, visitors and park personnel have often told of hearing vivid sounds of battle, experiencing “cold spots” or simply the sensation of being watched. More rarely, they have even encountered full blown apparitions. But pinpointing who-or what-was doing the haunting is in most cases unknown and unknowable.

Of all these paranormal activities related to Stones River Battlefield, none is better known than the Headless Horseman. Moreover, in the case of the Headless Horseman we believe we are better informed of the circumstances that caused his haunting, even though the gentleman in question lacks his tongue to talk to us with. The ghost in question was a blue-coat Yankee, a gentleman and officer of some renown: , Chief of Staff in the Army of the Cumberland, one of the Union Army’s best fighting force, even if historians have not always given this army its due credit.

The strange case of Colonel Garesché began several years before the war. He came from a devoutly religious family, whose beliefs included taking cursing and “taking the Lord’s name in vain” as a serious sin with dire consequences. When war came, the Colonel’s family took differing sides, leading to a family curse, ensuing prophecy and a fatal presentiment. The full story of Garesché’s presentiment of death is detailed in depth in Chapter 17 of Strange Tales. Our present concern, however, is with the aftermath; specifically with the events surrounding the Battle of Stones River in late December of 1862.

After Antietam, the Lincoln administration was impatient for his generals to provide the Republic with a decisive Union victory. Lincoln had announced the Emancipation Proclamation, which would take effect in January, and he did not want it to seem that it had been done from weakness rather than strength, especially to the British and the French, who were straining for any pretext to aid the cotton-rich Confederacy, whose raw material they desperately needed for their factories, a crop which in turn depended on slave labor to grow and harvest. The Battle of Antietam, earlier in the Fall was, at best, a draw even though General McClellan had literally been given Lee’s battle plans in advance. Despite knowing his opponent’s every move, McClellan still managed to turn what should have been a knockout blow to the Confederacy into an indecisive bloodbath.

Lincoln relieved the indecisive McClellan with someone he hoped would be more aggressive–General Ambrose Burnside. Burnside promised to give him a decisive win; he envisioned a rapid movement across the Rappahannock River and take the Confederate capital of Richmond before Lee could block the Yankee advance. In the actual event, Burnside’s “rapid advance” turned out to be a molasses-like maneuver, his army waiting on the arrival of engineers bringing pontoon bridges by wagon, along winter roads knee-deep in mud.

The Army of the Potomac, although admirably equipped and trained, was never an army fond of winter campaigning. They preferred to wait out the snowy months in their warm, comfortable bivouacs around Washington D C; the Federals, used to McClellan’s pampering, were in no hurry to attempt a winter crossing across the Rappahannock under fire into Fredericksburg.

By the time the bridging equipment finally arrived, any element of surprise the Federals had hoped for was gone and Lee had moved his army into well-fortified positions overlooking the town. Despite this, Burnside still ordered his men to attack, sending them into a death trap with no hope of success.

Even as they pressed Burnside into an ill-considered offensive in the east, Lincoln and his advisors were also pressuring General Rosecrans to commit his newly formed Army of the Cumberland to take the offensive in the west, ready or not.

Rosecrans at first resisted taking the field, protesting to Washington that his newly formed force was not ready. But by late December, impatient for a victory of any sort, the Lincoln Administration made it clear that he either advanced immediately or he’d be relieved of duty.

Facing Rosecrans was General Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, which had been consolidated from two Rebel armies that had invaded Kentucky earlier that Fall. While the Kentucky Campaign had not succeeded in taking the state, the Confederates could not be said to have been defeated and continued to threaten the Yankee army occupying Nashville.

Christmas in Nashville was filled with alarms and excursions, with Rosey’s regiments being notified to take the field on an almost daily basis, only to have the order rescinded hours later, General Rosecrans and his generals finally packed up their field wagons and portmanteaus and began an advance against Bragg’s boys, encamped just north of the city of Murfreesboro, along the meandering banks of Stones River, patiently awaiting the Yankees to join them for their shivaree.

The weather was less than ideal for marching, being a typical Tennessee mix of winter wet and cold, while the Union columns also faced constant harassment from Rebel cavalry. But by December 30, the Army of the Cumberland had arrived along the northern banks of Stones River, where the Confederates were patiently waiting their arrival.

There were no surprises in store for either army–or at least there shouldn’t have been–when battle began at first light on December 31st. Nevertheless, the Union right was taken, if not by surprise, at least unprepared, and suffered heavy casualties in the initial fighting among the cedar groves north of the river–what would come to be called the “Slaughter Pen.” American author Ambrose Bierce was at the time was a newly minted second lieutenant serving in General Hazen’s Brigade, on the Union left, and years later gave a concise description of the day’s fighting:

“The history of that action is exceedingly simple. The two armies, nearly equal in strength, confronted one another on level ground at daybreak. As the Federal left was preparing to attack the Confederate right the Confederate left took the initiative and attacked the Federal right. By nightfall, which put an end to the engagement, the whole Federal line had been turned upon its left, as upon a hinge, till it lay at a right angle to its first direction,” San Francisco Examiner, May 5, 1889.

Hazen’s Brigade sat at the apex of this giant V, anchoring the Union line in a part of the battlefield called “the Round Forest.” It was upon this vital spot that the Rebels turned the weight of their attacks to as the afternoon wore on. The Union right, having been forced back upon their rear areas, had managed to stabilize their line, which extended in a long diagonal from the Round Forest northwestward, with the railroad not far behind it as Bragg’s brave battalions continued launch attack after attack.

To encourage his men with his presence and make sure they continued to hold the line, General Rosecrans, along with Chief of Staff Garesché, and a few of their aides, trotted down the Union line on horseback.

Rosecrans apparently hoped that, seeing their commander and his second in command inspecting the front lines, it would have a calming effect on the troops, their lack of fear in the face of heavy enemy fire serving to encourage the rank and file. In the actual event the horses’ stately trot down the line turned into more of a jittery gallop, and what happened next to the Federal commander’s mounted party was anything but inspiring of confidence.

Far across the harvested cornfields, the long blue Yankee battleline was visible for some distance, even with clouds of brimstone-tainted smoke wafting across the open spaces. Behind that line one could clearly see old Rosey ride astride his mount, with Garesché close by on a snow-white stallion, both officer’s outlines silhouetted above the restless blue ranks. The two men were a tempting target and if perhaps too far for Rebel sharpshooters to hit with any precision, it was well within reach of Confederate artillerymen.

The officer in charge of one section of Semples’ Alabama Battery that day, was observing the Yankee lines through his field glasses when he caught sight of the group of Federals galloping boldly along, just behind the enemy’s main battleline. Gunnery Sergeant Hall told his superior he believed he could kill the exposed Yankee officer; Major Hotchkiss, also seeing the horseman, expressed the sentiment that, Yankee or not, that man was “too brave to be killed.” But war is war, and so they opened fire on the target.

Although the target was a good mile and a half distant, the solid shot came hurtling towards its intended victim General Rosecrans with amazing accuracy, missing him by inches. Sergeant Hall’s aim was as true and straight as the best Rebel sharpshooter’s might be, and he nearly did succeed in taking out the Yankee’s commanding general at a crucial stage of the struggle.

But Garesché, Rosey’s Chief of Staff and best friend, had been deliberately staying close beside his commander, hoping to spoil the aim of any sniper who might try to kill the general as they rode along in such a prominent manner. In this goal Julius succeeded admirably–at the same time fulfilling the dire prophecy his brother–a Catholic priest–had laid on him years before.

The black metal messenger of death narrowly missed General Rosencrans with only inches to spare–but found its mark close by with ghastly, gory precision. One second Julius was conversing with William; the next there was a flash of blood, brains and bone, vaporizing the colonel’s head. A fragment of the shell went on to wound an aide riding not far behind. With the command group was also riding a noted war correspondent Henry Lovie, who captured the moment of horror in graphic detail.

Field sketch by combat artist Henry Lovie depicting the moment that the Rebel shell killed Colonel Garesché, with notes for the magazine engravers as to the details. Library of Congress.

Field sketch by combat artist Henry Lovie depicting the moment that the Rebel shell killed Colonel Garesché, with notes for the magazine engravers as to the details. Library of Congress.Although Colonel Garesché’s head was gone, his body still stood erect in the saddle, astride the pale white steed, maintaining a proper military posture. It rode on for a short distance, as if the body had not quite got the message that its head was no longer along for the ride. After what seemed a long time, but in fact was but a few seconds, the trotting motion of the horse caused the headless corpse to teeter to one side and then slide off onto the ground. Colonel Garesché had made his rendezvous with death.

Rosencrans, badly shaken, rode on with the remainder of his command staff, trying to reassure his men that he was alive, well and unharmed. However, with his best friend’s brains, blood and gore splattered all over his head, face and uniform, the impression Rosey made on the troops as he passed by was less than encouraging.

Nevertheless, Rosecrans and his soldiers had far more to worry about than appearances, less they too ended up splattered all over the battlefield. The Federal army carried on with its deadly task, until nightfall at last brought an end to the day’s harvest of death.

About ten minutes after his death, Brigadier Hazen chanced to pass the spot where friend lay, not far from Hazen’s besieged command in the Round Forest. The spot where he lay was oddly still:

“He was alone, no soldier — dead or living thing — near him. I saw but a headless trunk; an eddy of crimson foam had issued from where his head should be. I at once recognized his figure, it lay so naturally, his right hand across his breast. As I approached, dismounted, and bent over him, the contraction of a muscle extended the hand slowly and slightly towards me,”

After the fighting subsided, Hazen ordered a burial detail to retrieve the headless corpse and had his West Point classmate interred in a shallow grave nearby. By lantern light, Hazen supervised his hasty burial, gathering his personal effects to prevent them from being stolen by those who haunt battlefields in search of loot.

Hazen supervised the hasty burial of Colonel Garesché’s headless corpse by flickering lamplight in unconsecrated ground. The headless rider is thought to be Garesché seeking his missing head.

Hazen supervised the hasty burial of Colonel Garesché’s headless corpse by flickering lamplight in unconsecrated ground. The headless rider is thought to be Garesché seeking his missing head.We know the time, place and manner of Garesché’s demise. The manner of the Headless Horseman first appearance is less certain. We hear of few, if any, apparitions directly after the Civil War. It is thought the trauma of what the soldiers and civilians alike had experienced was still too fresh in their memories and there were few who wished to open old wounds by recounting odd or supernatural experiences, no matter how real they may be. Mention of the Headless Horseman, as well as the numerous other ghosts related to the battle, were first committed to print sometime in the early twentieth century.

As for Colonel Garesché, although he had enjoyed benefit of clergy just before the battle, his own deep religious beliefs may have contributed to his spirit’s restless roaming. When he took the Lord’s name in vain and cursed his Secessionist relatives, he believed that, in turn, provoked a curse upon himself as well.

His brother, a priest, had a strong strain of fatalism mixed in with his religious faith and believed there was no way to lift the curse his soldier sibling had provoked. Then too, burying of the body in un-hallowed ground, even temporarily, may have unwittingly unleashed uncanny supernatural forces, the sort of entities who “roam the world, seeking the ruin of souls.”

Whether the Headless Horseman only makes his appearance on the anniversary of his death, or whether he is apt to appear at other times, is not certain. At least one re-enactor spotted him riding close beside the train tracks while they were encamped on the battlefield at night; National Parks staff have observed his phantom transit at various times. Moreover, CSX train crews have spotted the Headless Horseman riding parallel to the rails from time to time. Others assert they see him recreate his fatal ride when the moon is full and frost is in the air.

What is known is that the Headless Horseman rides besides the rails up to the present time and while one may debate when he rides or why, no matter how many times he rides and at whatever hour his visage is seen, one fact is certain: no matter how often he repeats his fatal ride, he will never, ever, find his head again.

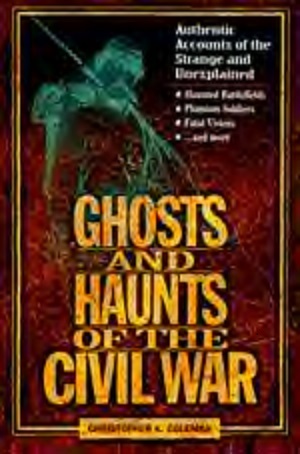

For more true accounts of the supernatural and the Civil War, read Ghosts and Haunts of the Civil War and The Paranormal Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. For more about the Army of the Cumberland and the Battle of Stones River, read Ambrose Bierce and the Period of Honorable Strife, chronicling American author Ambrose Bierce’s wartime experiences with the Army of the Cumberland.

Strange Tales

relates authentic accounts of haints, haunts and unexplained events, past & present, in the Mid-South.

Strange Tales

relates authentic accounts of haints, haunts and unexplained events, past & present, in the Mid-South.

Ghosts & Haunts of the Civil War. Authentic accounts of haunted battlefields, CW ghosts and other unexplained phenomena.

Ghosts & Haunts of the Civil War. Authentic accounts of haunted battlefields, CW ghosts and other unexplained phenomena.`