Concei��ao do Araguaia, Mass Email

Dearfriends and family,

We last emailed you fromBarra do Gar��as, Brazil, where we awaited parts to fix our outboard motor again.We bought two cylinder/piston sets and had them sent separately via UPS in hopesof getting at least one set soon. On March 25 both packages reached S��o Paulo, whereupon we were instructed to go to a bank and pay importduties amounting to 100% of their value including exorbitant shipping costs. Butthey didn���t come anywhere near when promised, and our inquiries produced vagueresults.

We were holed up in acovered storage compound belonging to our friends the ice cream makers who wereoff travelling in their motor home. We had a room, a shower, and a refrigerator.Life was good. To fill our days we took hikes. We visited a popular hot spring,where we lounged in a series of beautifully landscaped pools, and hiked tomisty waterfalls in the nearby hills.

Thurstonwas tied up to the floating restaurant down at the port. One day while gettingsomething from the boat we noticed rat turds and chew marks! Steve looked forthe culprit with no luck and we assumed he had left. When we were ready toleave it was clear he was still aboard, so we moved Thurston to a beach and shifted everything from the cabin onto thesand until there was no place left to hide. Suddenly the small rat broke cover.He scrambled about until Steve killed him with a bamboo pole. He had torn holesin our packaged food and various articles made of fabric. This would be theeasiest rat to kill.

On April 8 the firstcylinder and piston arrived! Overjoyed, we took them to our mechanic, God��, aretired native of S��o Paulo. He had no sophisticated tools but was wonderfullywise and pleasant to work with. The cylinder had factory defects, so Stevehopped on a motorcycle taxi and took it to a machine shop, which installedmissing threads. Finally we got the motor back together. Neither God�� nor themachinist accepted any money for their services.

We moved aboard back Thurston, re-immersing ourselves in lifeat the port, where grandstand-like steps marched down into the water. By day peoplesat looking out over the macho jet-skiers who zoomed back and forth, turning ona dime and shooting up maelstroms of foam. One guy specialized in ridingbackwards. Another guy acted like a matador. While spinning his machine hestood with both feet on the floorboard to the inside of the spin, one hand onthe throttle, the other arm waving gracefully in the air as if he were waving aflag at a bull. The jet skiers stayed in front of the steps as if they were agrandstand. It was purely a spectator sport.

That was the daytime. Bynight the port rocked with folk music and happy partiers. In the morningmunicipal workers picked up the garbage and woke up the drunks still asleep onthe steps.

The motor requiredfurther debugging due to a leaky oil seal and a dirty carburetor. The rats keptcoming and the stove and backup stove were nearly out of commission. We werebeginning to feel like Barra do Gar��as was against us! However, it would beweeks before we reached a town as large as Barra, so we had to be sureeverything was in order. Five trips to the mechanic, two aborted attempts toleave and two more increasingly clever rats later brought us to April 12. Thoughleery of our cursed Honda, we cast off! We kept the motor barely above idle tobreak it in gently. We were eager to get some kilometers under our keel becausethe rapids two-thirds of the way to Belem would get worse as the dry seasonprogressed, lowering the river level and exposing rocks.

The tall hills soonmelted away, leaving only low, green banks. Almost nobody lived along theriver, nor was there any farming. If we managed to squeeze past the mattedriverine brush we found vast expanses of twisted trees, tall grass, and palmshrubs with thorns like six-inch needles. We settled into travel routines,waking at day break as George crawled over us. Steve made breakfast in thecockpit, then rowed after if it wasn���t yet too hot. Motored through lunch,George splashing in the cockpit off and on all day as we dumped water on him.An afternoon break to explore a beach, town or bank, late afternoon row, then asunset stop in the least buggy place we could find. George played in thecockpit with Steve reading ���As Viajens do Gulliver��� (Gulliver���s Travels) overand over and over again, while Ginny prepared dinner. Steve operated the stovewhile Ginny and George read ���As Viajens do Gulliver��� over and over and overagain in the cabin. Eat, clean up, pass out. A simple life can be quiteexhausting!

The river, initiallyaround 500 meters wide, spread more and more with the addition of newtributaries. Because these were relatively clear, the soupy-orange Araguaiabecame clearer until visibility reached one foot. At first we ran onto sandbarsand had to pull ourselves off. But perhaps the tributaries were at a higherstage than the Araguaia because as we proceeded north the banks got fuller, thesandbars fewer.

Every morning thetemperature quickly rose into the 90s and up and stayed there until lateafternoon. The only time we saw a thermometer it was 94 in the shade and 114 inthe sun. We all developed itchy heat rashes. The cockpit was okay with theawning up and the artificial breeze of the moving boat, but the cabin wasunbearable, partly because the varnished cedar of our cabin absorbed too muchheat. So, we stopped in a small town and painted the sides white (we had previouslypainted the top white). We frequently doused ourselves and George with thebailer bucket. At night, even with the fan on the cabin became too hot for allthree of us, so Steve slept curled up in the cockpit footwell, a space abouttwo feet by four feet!

Clothing was optional exceptto combat insects. By day midges caused swollen bites if we stopped at a beach.Biting flies sometimes found us on the river. Mosquito necessitated nets fromsunset to sunrise. Other insects were simply a nuisance. At night our headlampsattracted beetles and flies small enough to get through our nets and tickle ourfaces. Flying crickets swarmed the cockpit, crawled under Steve���s net, and pesteredhim. They all died during the night and required mopping up in the morning.

Ginny launderedincessantly. Sitting in the cockpit she stretched the articles out on deck, scrubbedthem, and rinsed them in the river. They dried lightning-fast on the linerunning from stem to stern. Steve ramped his rowing up to two hours per day,mostly in the early morning and late afternoon when the heat was less intense.He soon felt the beneficial effects in his arms and shoulders.

We saw toucans, roseatespoonbills, and tuiuius, the bigwhite stork with a red neck. Blackbirds gobbled like turkeys until they allroosted together in a tree, then they whirred like cicadas. We were happy toreacquaint with our old friends the Venezuelan Mohawk-Hairdo Chicken and theParaguayan Eagle. We call them by these names, never remembering what they arereally called. They are probably neither chickens nor eagles.

Fishermen in aluminumskiffs were a frequent sight. They were friendly, not nosy. Every couple days wepassed a town with a hotel or two which catered to them. We took theopportunity to stretch our legs. We walked a wildly grinning George between us,each holding one of his hands, until he got tired. Then we put him in thecarrier on Steve���s back. The towns were small and neat, with buildings ofstuccoed brick, painted with a darker band on the bottom. Their river-frontswere protected by walls of mortared stone, atop which plazas faced the river. Tosee the surrounding country we walked to the edge of town, where a connectingribbon or dirt or asphalt roadway receded across the limitless plain or swamp.Then we walked back to the boat, stopping for a 600-milliliter bottle of Skolor Antartica beer on the way. With any luck the bakery might have some breadrolls and the fruits and vegetable store might have some mangos or carrots.

Because mosquitoescongregate around vegetation we got into a habit of getting as far as possiblefrom greenery when evening came. Sometimes we followed still channels intooffshoot lagoons and anchored out in the middle. The mosquito hour was milderthere than tied to a bank. We also slept where islands were about to immerge,tying to brush or anchoring in sand. On one such night, far from any real land,we waded in current-swept shallows as the sun set. The coarse sand had thedisconcerting tendency to give way until one was buried up to ones ankles. SuddenlySteve saw a flash of silver and felt something brush against his ankle. He hadbumped into a freshwater stingray but its spiny tail had failed to penetratehis skin. Stingray wounds are notoriously painful.

As we travelled downriverthe land got ever swampier. On our right, over the course of a week we passedIlha Bananal (Banana Tree Island), supposedly the world���s largest fluvialisland. It was more swamp than island, a vast maze of channels and lagoonsstudded with gnarly old snags. There were no signs of people on land, and fewon the river. Dark grey dolphins (apparently the same as the pink dolphins weencountered before) often followed us. Otters snorted and tumbled in the water.Alligator eyes glowed pink in the night along the marshy shore. Howler monkeys raisedtheir cacophonous din, unseen in the forest.

Ginny had probably spenta hundred hours on Google Earth building our GPS map for the Araguaia due toits countless islands and channels. Her map was reasonably accurate except thatthe imagery was shot during low water, so the river was much bigger than the mapshowed. We often navigated where it showed land. Once we got stuck in a deadend, when a strong current dissipated into brushy swamp, forcing us to motorback to the main channel. We often never knew if channels we passed were tributaryrivers or sister portions of the Araguaia, delineating islands. To build thatlevel of detail into the mapping would have required three times as much work.

Rarely was the rivercompletely calm. Minute swirls etched its surface. Whirlpools and upsurgessuggested bottom disturbances such as rocks or sunken logs. Ripple lines markedthe downstream end of sandbars, where shallow water became deep again. If wegot to that line without running aground we would be back in deeper water. Theislands were rarely flat or of one piece. More often we saw a myriad of smallislands separated by knee-deep channels. They were studded with pools, dunes,and copses of low trees.

On April 30 we reachedS��o Felix, Mato Grosso. By Facebooking with our friend in Barra do Gar��as wefound that our second package had arrived, so we waited four days while heshipped it by bus. S��o Felix is in the land of the Caraj��s, a major indigenousgroup. Every second person on the street was Caraj��s, and the town was full ofgovernment offices catering to their needs. They generally had tattoos, thewomen with geometric bands around their calves, with men with crude circlesaround their cheekbones. We befriended a Caraj��s biologist with a spottedleopard running down his arm who told us a little about his people. Many ofthem live in small aldeias with mud and wattle houses coveredby thatched roofs. Other people are allowed to visit, but it is against the lawto take photos of anyone. In his youth they used to grow maniocand maize on the emerging islands, but now many depend on government providedfood. He also explained a little about their spiritual beliefs, how they greetthe sun when it rises, say goodbye when it sets, and how they salute the riverand other natural spirits. This biologist had once travelled to Wyoming on anexchange program to visit with the Arapaho tribe. He said he saw many similaritiesbetween them and the Caraj��s.

S��o Felix���s outskirts containednew subdivisions for the rural poor. They had dirt streets and tiny brickhouses. The houses often had only of one pitch of roof, but after they hadaccumulated enough building materials they built the other pitch, doubling thesize of the house. We often saw stockpiles of sand, covered with bricks toprotect them from rain, the mounds looking like graves. Crude signs advertised cottageindustries such as popsicles, fish, and culinary specialties.

Travelling downriver issuch joy! This is our third such leg, the other two being the Casiquiare/Negroand the Paraguay/Paran��. For weeks on end one drifts with the current,supplemented by such movement through the water as one cares to effectuate. Rowingis feasible and motoring can be done at slow speed, thus quietly and withlittle fuel consumption. The scenery changes quickly. We started seeinghills. The state of Tocantins now lay to right, the state of Par�� to left. Wesaw our first sea horizon: a short patch of horizon with no land, howeverbriefly, though we were still far from the sea. The river was now a mile wide.

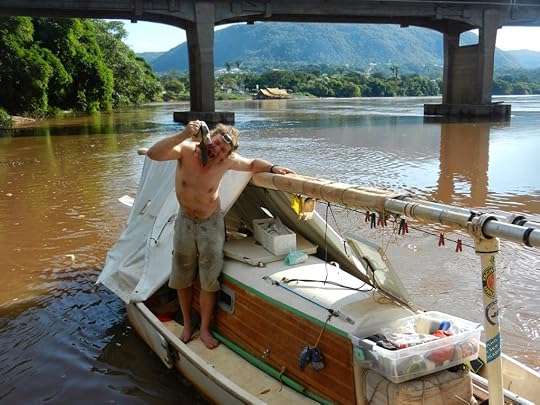

On May 11 we reachedConceic��o (Conception), a city the size of Barra do Gar��as. The shore was linedwith planked canoes with long-tail motors. We tied up to an out-of-servicetourist boat and explored the city. A local family has adopted us, feeding usdelicious fish and cakes and showing us around town. It is a good place topause for a while.

We are happy to becruising again. It is a life full of continuity yet renewal. We are always thesame Steve, Ginny, and George in the same Thurston,yet we are always in new places. We keep things fixed, keep ourselves clothedand fed, and make progress toward our goal. We set a leisurely pace, yet we arebarely able to stay awake until 9:00, so full are our days with parenting,small-boat contortions, and the myriad labors of travel.

Some new photos may befound at: https://picasaweb.google.com/ginnygoon/BrasilPart4

Lots of love,

Steve, Ginny, &George

Published on May 14, 2014 10:45

No comments have been added yet.