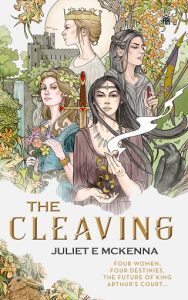

Tackling The Guinevere Problem in The Cleaving – Juliet E. McKenna

This depiction of Queen Guinevere by John Collier, painted around 1897, sums up the challenge this particular character poses for anyone re-examining the Arthurian mythos from a female-centred or feminist point of view. This Guinevere is as passive as she is beautiful. An ideal who keeps her mouth shut. She’s not even holding the reins of her own horse as she’s led along as Queen of the May, obediently using hawthorn sprays to frame her lovely face.

This painting specifically refers to Tennyson’s version of Guinevere in his ‘Idylls of the King’. When the court returns from this Maying procession, Sir Lancelot sees sneaky Mordred spying on Guinevere and her maids. Lancelot smacks Mordred about a bit and sends him on his way. When he tells Guinevere though, she is seized with such uncontrollable desire for Lancelot that she runs away to a convent. The sin, Tennyson repeatedly tells us, is the queen’s. She’s the wife. Lancelot is single. By running away, she makes things worse. Conflict between Arthur and Lancelot follows. Mordred usurps the throne and everything is Guinevere’s fault. Not that she does anything about it, sitting in her cloister and lamenting.

This version of Guinevere is a prime example of the uses Victorian writers and artists made of the Arthurian mythos. Portraying Arthur as the noble and kingly ideal promoted loyalty to the crown, and not-so-incidentally gave Queen Victoria’s rule a spurious gloss of ancient, revered tradition. This worked so well that many modern readers are unaware how insecure Victoria’s seat on her throne was at times. Lancelot and Guinevere’s adultery is an undeniable element of the story so Tennyson cannot ignore it, but if Arthur’s the ideal king, he cannot be at fault. Lancelot is the epitome of chivalry, so he can’t be at fault either. Guinevere must be in the wrong, playing into every patriarchal prejudice about weak-willed women that Victorian society sought to uphold, in an era where real-life women were demanding the right to think for themselves, to ride bicycles, to wear rational dress, and to vote.

What’s a 21st century writer supposed to do with that level of misogyny?! It’s no wonder some authors offer wholesale rewrites of Guinevere’s character, especially in those versions of the myth looking for a plausible ‘historical’ Arthur. Keira Knightley as kickass Celtic warrior maiden in the 2004 movie King Arthur leaps to mind. And that’s fine, if that’s the story the author wants to tell. But that’s not what I set out to do in The Cleaving. I wanted to look at the core familiar story, and to interrogate that tradition from a different perspective. A female perspective. What am I supposed to do with a witless, weeping Guinevere who’s so wet you could wring her out?

Unless … her story offers an opportunity to highlight a facet of feminism that can be too often overlooked. Epic fantasy fiction has challenged the stereotype of the damsel in distress for decades, but the alternative most frequently presented is the kickass warrior maiden. She takes on the boys at their own games, and she wins. I’ve seen such heroines labelled ‘faux-male’. They have their place, don’t get me wrong, but they can unintentionally imply masculine strengths and virtues are superior. Where does that leave women without the strength or the desire for confrontation? Where does that leave the so-called ‘soft’ skills of negotiation, organisation, communication and cooperation, which are so often cited as women’s strengths?

This was the key to following Guinevere’s traditional narrative in the story I wanted to tell. This Guinevere is content to enter her arranged marriage. She strives to be a good wife. She obeys her husband, rarely speaks unless spoken to, and does her duty to look decorative without question. She uses those soft skills to unobtrusively support the king. Playing by these rules doesn’t save her though, when she is blamed for things entirely beyond her control. When this provokes her into crossing a line, the patriarchal double standard means there’s no way back for her. The more I worked on this book, the more I realised her story was an essential counterpoint to Morgana’s strong-willed independence.

These elements are already there in the classic Arthurian tradition. Drawing them out and challenging them from a 21st century female perspective gives a very different Guinevere as a once and future queen.

Juliet E McKenna is a British fantasy author living in the Cotswolds, UK. She has loved history, myth and other worlds since she first learned to read. Her debut epic fantasy novel, The Thief’s Gamble, began The Tales of Einarinn in 1999, followed by The Aldabreshin Compass series, The Chronicles of the Lescari Revolution, and The Hadrumal Crisis trilogy. In 2018 The Green Man’s Heir began an ongoing contemporary fantasy series rooted in British folklore. The sixth novel will be published later this year. Her wide-ranging shorter fiction includes dark fantasy, steampunk and SF. The Cleaving, from Angry Robot, is her female-centered retelling of Arthurian myth.

Please Feel Free to Share: