Cowboys

When I was growing up, just outside New York City, I saw a lot of cowboys – on television. First were shows like “The Lone Ranger” and “The Roy Rogers Show,” where I learned that cowboys had wonderful horses, like Silver and Trigger, they dressed in big hats and fancy shirts, they had a six-shooter on their hip, and they were strong men who upheld the law, even in the lawless West, wherever that was. After lots of chases on horseback, gunfights, and fistfights, they always caught the bad guy.

Some of the TV cowboys sang. Gene Autry sang “Back in the Saddle Again,” among other hits. Roy Rogers and Dale Evans sang “Happy Trails to You” at the end of each episode of their show.

https://www.google.com/search?q=happy+trails+to+you+youtube&oq=Happy+Trails+to+you+YOuTube&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBggAEEUYOzIGCAAQRRg7MggIARAAGBYYHjIICAIQABgWGB4yCggDEAAYhgMYigUyCggEEAAYhgMYigXSAQ8xNzY4NjU1MTE0ajBqMTWoAgCwAgA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:bc2e0bbd,vid:eEqUyNaSdvgSo a cowboy, as far as I could tell, was a handsome White man with a good heart, a fine voice, spotless clothes, and a great horse.

I wasn’t the only one watching cowboys on TV back then. In 1959, eight of the top ten shows on TV were westerns.

Later on, the cowboy image got a little more complicated and lost the singing bit. Zorro was a masked man, like The Lone Ranger, but he fought against political corruption in the ruling class, even though he was part of it. And he used a rapier rather than a gun.

“Have Gun, Will Travel” presented Paladin, a “knight without armor in a savage land,” a hired gun with a conscience – and a good deal of education. He often quoted Shakespeare or other poets while he was confronting evildoers.

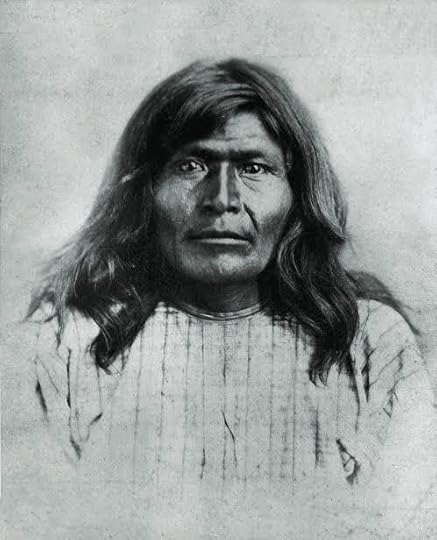

“Bonanza” was the saga of an empire built on family. Pa Cartwright and his three sons made a formidable group. The image of them riding four abreast toward the camera at the beginning of the episode reinforced the idea of their collective strength. The show was so popular that horse-crazy fans could buy Breyer models of the horses the Cartwrights rode: Sport, Chubb, Buck, and Cochise. If I had known anything about American Indian history back then, I would have found that name a strange choice, since Cochise (photo) was a famous Apache leader who fought against White expansion into their land.

But that’s only one of the problems with the TV westerns’ image of cowboys of the Old West.

“The birthplace of the cowboy”

Deep Hollow Ranch in Montauk, at the tip of Long Island, New York, claims to be the oldest ranch in the Americas, “the first home of home on the range” and “the birthplace of the American cowboy.” That claim comes from the fact that European settlers as early as 1658 used the lush grasses and natural boundary of the sea to keep cattle there.

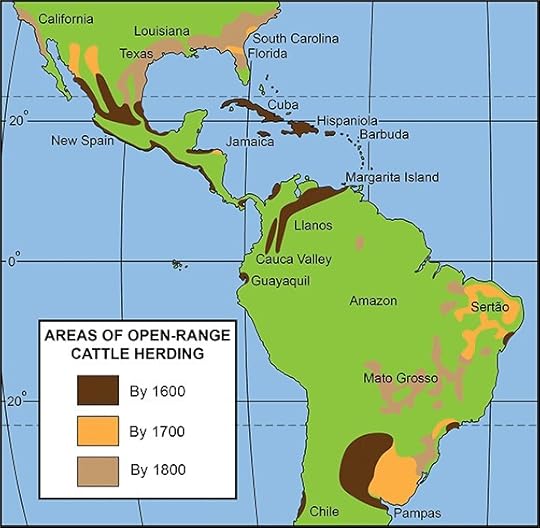

But others beg to differ about the earliest cowboys. In 1493, Christopher Columbus brought the first cattle to Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). As the native Taino population declined from disease, enslavement, and loss of resources, the cattle herds increased. Eventually, the Spanish landowners needed men on horseback to round the cattle up so they could be slaughtered for leather, tallow, and meat. These men, mostly sub-Saharan Africans, developed the technique of swinging a rope from horseback in order to catch cows.

From there, cattle ranching spread to Puerto Rico (1505), Jamaica (1509), and Cuba (1511). The first official land grant for a cattle ranch in Mexico was 1519. The Spaniards were familiar with keeping cattle on large tracts of dry grassland too big to manage without the help of horses. As you can see in the graphic, cattle ranching in the pampas of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico was well-established by 1600. All long before Deep Hollow Ranch was founded.

Vaqueros

The men who worked on the cattle ranches of New Spain, especially Mexico, were called vaqueros, from vaca, Spanish for cow. Most of these people were mestizo (mixed Spanish, Indigenous, and African descent). They braided rope from strips of leather and horsehair, made their own saddles and bridles, broke and trained horses, protected the cattle from predators, and managed the long drives from grazing areas to markets.

In 1845, The United States annexed Texas. Then President James K. Polk sent an emissary to Mexico City offering to buy California and New Mexico for $30 million, but the Mexican President refused to see him. In 1846, when skirmishes erupted along the Rio Grande, Polk used them as an excuse to declare war against Mexico. According to the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ratified in 1848, the US gained Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

As the Mexican landlords left, they abandoned most of their cattle, but many of the vaqueros stayed with them, becoming the cowboys of the new ranchlands. It’s estimated that a third of the cowhands in the American West were vaqueros.

African Americans

White Americans seeking cheap land moved into Texas even before the Mexican War, and they brought enslaved people with them. By 1860, slaves accounted for about 30% of the population. Texas joined the Civil War as a slave state in 1861, and many of the ranchers left their land to fight for the Confederacy. In their absence, the enslaved workers honed the skills necessary to care for horses and cattle. By the time the landowners returned at the end of the war, they found they had to hire now-free African Americans as paid cowhands. Demand was even greater when ranchers began selling their livestock in northern states, where prices were much higher. That meant long cattle drives to get the herds to newly created butchering centers and railroad hubs. The rough life of the cattle driver created a far more accepting environment for the former slaves than they knew before. Nat Love, an African American cowboy, said of the cowboys he worked with on the long drives, “A braver, truer set of men never lived than these wild sons of the plains whose home was in the saddle and their couch, mother earth, with the sky for a covering.” While that’s a fine sentiment, it’s worth remembering that the cowboy’s life was physically demanding, often dangerous, and paid very little. If he was thrown from his horse or gored, there was no Urgent Care or hospital around the corner. Many ranchers paid so little that the hands were essentially given only room and board.

Bill Pickett, a cowboy born in 1879 to former slaves, became famous for inventing “bulldogging,” a technique for wrestling a steer to the ground that later became a popular rodeo event.

Another formerly enslaved Black cowboy, George McJunkin, born in Texas in 1851, made history with a discovery that rocked the archaeological world. He was a self-taught naturalist and collector of ancient stone tools, as well as manager of the Crowfoot Ranch in New Mexico. After a flash flood swept through the area, he spotted what looked like enormous bison bones sticking out of a wash. He brought some back to his cabin. For fourteen years, he tried to get people to listen to him about the importance of these bones. He knew they weren’t modern bison bones. Finally, after McJunkin’s death, a blacksmith McJunkin had told about the bones convinced a banker named Fred Howarth to check out the site. Howarth enlisted the help of experts from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. In 1927, a team excavating the site found a stone spear point embedded in one of the enormous bones. They left it there and invited other experts to see it. It rewrote the history of humans in the Americas because it meant humans had been in North America much longer than previously thought.

It’s estimated that one in every five cowboys in the heyday of the cattle drives was Black Add that to the mixed heritage of the vaqueros.

A short but intense period

Between 1850 and 1890, the US expanded westward rapidly as settlers poured west in search of free land. Rail lines spread across the country, joining east to west in 1869 with the pounding in of the famous golden spike in Promontory Point, Utah. Then cattle could be driven from the Texas range to the rail hubs for shipment to the cities of the north and east, as well as the west coast. There were fortunes to be made. One cattleman bought 600 cows for $5400 in Texas and sold them in Abilene, Kansas for $16,800. He was not alone.

Suddenly, manpower was needed everywhere – to drive the cattle, to build the railroads, to build the stock pens, to establish butchering facilities and transport routes.

Chinese

The backbreaking work of building the western section of the transcontinental railroad was made possible by about 20,000 Chinese immigrants. Seen as a good source of cheap labor (like the Irish immigrants on the eastern sections), they were assigned the dangerous work of blasting through the mountains to lay track. Many were injured or killed in the process.

In addition to construction, Chinese immigrants worked as cooks, blacksmiths, miners, and farmers. When the railroad work was done and local communities forced out Chinese people, some wound up working for the cattle ranches, as cooks and as cowboys.

Jim Sam, a famous Chinese cowboy (photo), was born in China in 1859 and brought to California the following year. Later, he worked for two ranchers, doing everything from milking cows to cooking. He became an excellent horseman and joined the cattle drives for many years. Later he ran a hotel and enjoyed pretending he didn’t know anything about playing cards so he could relieve bragging visitors of some of their cash.

American Indians

Despite the Cowboys vs. Indian battles made popular in the Wild West Shows, there were many Indian cowboys in the heyday of the cattle drives. With the bison slaughtered by buffalo hunters and their people forced onto reservations, some Plains Indians set up their own cattle operations or sought work with White ranchers. They were, like the Black and Chinese cowboys, treated as inferior, but their skills, especially with horses, were essential to a successful cattle drive.

Others

Ranch work also attracted desperados – men who, for one reason or another, had to leave home. Some were wanted men. Some had lost everything in the war. Some, because of their race or ethnicity, were widely hated. Some had a past they’d rather forget. But the cowboy’s life was so demanding, it meant having to trust others in the group. Generally only eight to ten cowboys would be expected to take a herd of 300 cattle on a drive of up to a thousand miles across open country, with only a cook and a foreman to help. That meant dealing with thieves, outlaws, angry landowners, accidents, disease, drought, floods, and danger of stampede or splits. While they might not be best friends, the cowboys absolutely depended on each other – and their horses – for their survival.

Probably the best modern representation of the mix of people who were cowboys in the Old West is the 2018 remake of The Magnificent Seven (shown).

Women

Though there were probably cowgirls back then other than Annie Oakley, they don’t show up much in the historical record. Only the homesteaders like Laura Ingalls Wilder of The Little House on the Prairie fame. And the outlaws. Like Belle Starr, who dressed in black velvet and rode sidesaddle, carried two pistols and was a crack shot. She married Sam Starr, of the Starr clan, a Cherokee Indian family known for horse stealing and other crimes.

Pearl Hart was a Canadian outlaw who teamed up with Joe Boot to commit one of the last stagecoach robberies in the American West.

Lottie Deno was a notorious gambler who married another gambler who was wanted for murder. She was apparently the inspiration for Miss Kitty on “Gunsmoke,” though it’s hard to see the connection between the two. Miss Kitty never seemed to have a dark past she was running from.

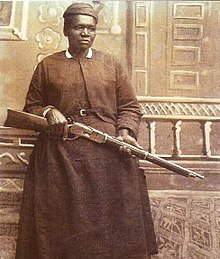

Mary Fields (photo), born into slavery around 1832 and freed after the Civil War, went to work first in Ohio, then Montana, where she became famous for drinking, smoking, and toting guns. In 1895, she became the first African American stagecoach driver, famous for her courage in standing up to bandits. Rumor has it that she fought off a pack of wolves by herself. Sounds like a great idea for a movie.

The other women, the ones who worked hard on the ranches to made them successful even in the face of constant challenges, are seldom mentioned.

The end of an era

In the 1880s, the beef boom collapsed. A drought in 1883, combined with overgrazing of some areas and more people moving into former range land, meant insufficient grass available to sustain the herds. The winter of 1886 – 87 was so cold many cattle perished.

In 1874, Joseph P. Glidden of Illinois patented barbed wire fencing for cattle. Gradually, its use changed cattle ranching. Larger operations survived, but smaller operations could no longer count on enough open range to fatten the cattle. By 1900, the open range was gone, and part of the cowboy life went with it. Cowboys typically went to work for the big operations instead of trying to run their own.

The new image

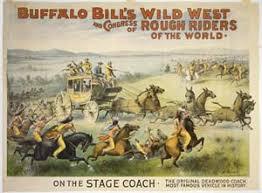

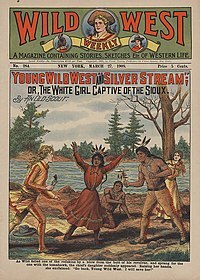

But almost as soon as the old cowboy life changed, the idea of it was picked up, embellished, and presented to the public. Wild West shows sold a dream of endless space, freedom, challenge, and adventure.

Dime novels and weekly magazines told exciting, serialized stories about savage Indians, brave mountain men, outlaws, and constant danger. “Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter,” published in 1860, is considered the first of the genre. Well past 1900, magazines like The Wild West Weekly were still popular reading, especially in the east.

Western novels, like The Virginian by Owen Wister (1902) and Riders of the Purple Sage by Zane Grey (1912), made the image of the tough, independent cowboy hero familiar to thousands of readers who’d never been west of the Mississippi.

So it’s not surprising that as early as the 1930s, radio shows featured the glorified image of the cowboy as an amazing yet self-effacing hero, like The Lone Ranger, a Robin Hood protecting the innocent and bringing the bad guys to justice, all the while avoiding any kind of self-aggrandizement. “Who was that masked man?” someone asks at the end of each episode.

But when it came to making these stories visual, somehow all the cowboys became White men. The 1951 film Tomahawk, about Jim Beckwourth, a famous Black frontiersman, featured a White actor in the part. In the 1956 film The Searchers, which was based on events in the life of Britt Johnson, a Black man, the character was played by John Wayne, a White man. And so on, through many films and TV shows, until gradually the real stories disappeared under the many coats of whitewash.

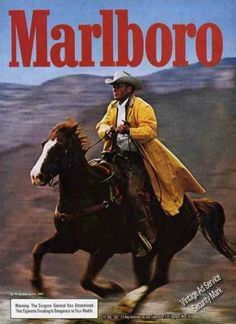

The Marlboro Man

Another image cemented the cowboy image in America’s mind – the Marlboro Man. The concept originated with a photo in Life magazine of Clarence Hailey Young, a foreman at the JA Ranch in Texas. It caught the eye of advertising executive Leo Burnett, who was looking for a way to make Marlboro cigarettes appeal to men. (They’d previously been pitched to women as “Mild as May.”) What could be more masculine than a cowboy? But perhaps not quite the weather-beaten man with the stubble beard in the photo. A more refined image. Darren Winfield, a rancher, was the first to be featured in the campaign, which was wildly successful. Over the next two years, sales of Marlboro cigarettes tripled – to $20 billion. The ads ran from 1954 to 1999, featuring various cowboys and models as the Marlboro Man. In the ads, Marlboro Country became the Old West of legend: vast, beautiful, and unspoiled. The Marlboro man was independent, strong, and handsome. And White. He wore a white or light tan cowboy hat, like the heroes of the old westerns, and he exuded quiet confidence and power.

Cowboys today

Of course, there are still working cowboys in the US, though many prefer to be called cowmen, and they still do the hard work on the ranch – breaking young horses, managing cattle, baling hay, fixing machinery, solving problems. It’s still hard work.

There are also rodeos that challenge cowboys’ traditional skills like calf-roping and bronc riding. While these were once off-limits to non-White competitors, they now include many Black, Latino, and American Indian cowboys.

And organizations like The Fletcher Street Riding Club and the Compton Cowboys are bringing the joy of riding and caring for horses as well as the idea of the Black cowboy into urban neighborhoods.

Thoughts

The erasure of some groups of people from our history and our popular culture isn’t just their loss. It’s ours too. These are people who need to be recognized and amazing stories that need to be told. Perhaps now we’ll get to hear more of them.

Sources and interesting reading:

Beardsworth, Jessie, “How the Marlboro Man Changed Advertising,” JTTB blog, https://jttbblog.com/jttb/how-the-marlboro-man-changed-advertising

“Black and Mexican Cowboys Made Up At Least 25% of the Old West,” History Daily, https://historydaily.org/black-mexican-cowboys-facts-stories-trivia/4

“The Cattle Industry in The American West” History on the Net, https://www.historyonthenet.com/american-west-the-cattle-industry

“Cowboy” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org.wiki/Cowboy

“Cowboys,” History.com, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/cowboys

Fox, Courtney, “10 Women Who Ruled the Wild West,” Wide Open Country, 5 May 2022, https://www.wideopencountry.com/women-of-the-wild-west-10-legendary-women/

“Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, the Singing Cowboys,” Movie Man Eric documentary on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pb1dW7Njs8c

Gandhi, Lashmi, “How Mexican Vaqueros Inspired the American Cowboy,” History, 2 September 2021, https://www.history.com/news/mexican-vaquero-american-cowboy

“Happy Trails to You” sung by Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, with lyrics, YouTube, https://www.google.com/search?q=happy+trails+to+you+youtube&oq=Happy+Trails+to+You+YouTube&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBwgAEAAYgAQyBwgAEAAYgAQyBggBEEUYQDIICAIQABgWGB4yCAgDEAAYFhgeMgoIBBAAGIYDGIoFMgoIBRAAGIYDGIoF0gEPMTc1MzA2ODM3MGowajE1qAIAsAIA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:541991d8,vid:oG_fSoYFWLA

Jafri, Dr. Beenash, “Asian American Cowboys and Native Erasure,” UC Davis Diversity, Equity and Inclusion blog, reprinted from Reappropriate, 22 September 2022, https://diversity.ucdavis.edu/articles/blog/asian-american-cowboys-and-native-erasure

Lee, Donald, Forth Worth Herd Drover, “The History of the Mexican Vaquero,” Western Experience, 25 August 2021

Livingston, Dewey, “Jim Sam: The Legendary Chinese Cowboy,” Anne T. Kent California Room Newsletter, 15 September 2020, https://medium.com/anne-t-kent-california-room-community-newsletter/jim-sam-the-legendary-chinese-cowboy-66d806a29983

Nash, Stephen, “ A Hidden Figure in North American Archaeology,” Sapiens, 20 January 2022, https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/George-mcjunkin/

Nodjimbadem, Katie, “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys,” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 February 2017 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lesser-known-history-african-american-cowboys-180962144/

Sayre, Nathan F, “Review of Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500 – 1900 by Andrew Sluyter” Pastoralism Journal, 2014, https://pastoralismjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13570-014-0008-3

Seah, May, “Why the new Magnificent Seven has an Asian Cowboy,” Today, 18 September 2016, https://www.todayonline.com/entertainment/movies/why-new-magnificent-seven-has-asian-cowboy

“Vaquero,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaquero

Western, Samuel, “The Wyoming Cattle Boom, 1868-1886” WYOhistory.org: A project of the Wyoming Historical Society, https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/wyoming-cattle-boom-1868-1886

Welch, Bob, “Native American Cowboys: Jackson Sundown, Tee Woolman and Doyle Lee,” The Team Roping Journal, 12 January 2012, https://teamropingjournal.com/ropers-stories/native-american-cowboys-jackson-sundown-tee-woolman-and-doyle-lee/

“Westerns on television,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_on_television

Williams, Leah, “How Hollywood Whitewashed the Old West,” The Atlantic, 5 October 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archieve/2016/10/how-the-west-was-lost/502850/