“Inevitable contact”? – and matters of conscience

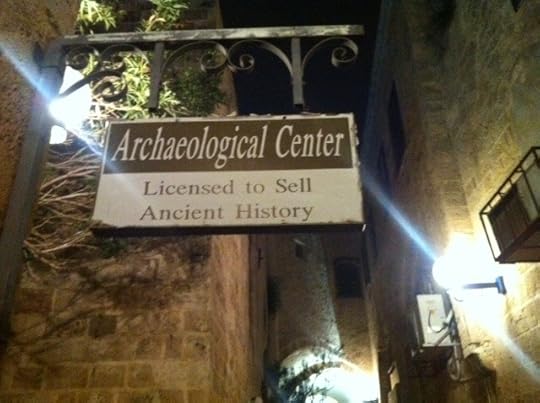

Protect your history! A sign in Jaffa

I had always thought that if I got an invitation to go to Israel to work with teachers and students there I would refuse. Israel, the big bully of the Middle East, building, by force, settlements on Palestinian land they are not entitled to; carving a great big wall through territory they have no right to; using maximum force in densely populated areas where civilians are, of course, slaughtered in their hundreds; boarding peace convoys in international waters so ineptly that people died.

But I know, too, that Israel is the target for rocket attacks, and that not all the Gaza flotilla personnel were peace-loving saints; I know that Israelis – innocent Israelis – have been killed by rockets, in restaurants and in buses. That all Israelis have a well-founded fear for their safety.

But still. They way the Israeli military behaves, with its daily humiliations of Palestinians and murderous retaliations for any wrong done to it strike most people I know as unacceptable in every way.

As a boy I thrilled to Leon Uris’ great saga of Zionism, Exodus, which told of the founding of modern state of Israel. Only later with populist books such as O Jerusalem! by Larry Collins and Dominc Lapierre did I begin to understand at what price this state had been born and about the ineptitude and culpability of the British for the great mess of the Middle East. It takes time to see things clearly.

Two of the most moving and meaningful books/plays I encountered in the 1990s were Inherit the Truth by Anita Laski Walfisch (about the cellist’s amazing survival, with her sister, in the horrors of Auschwitz – where she played in the camp orchestra – and Belsen) and (a play based on the writings of the 23-year-old American who was murdered by an Israeli bulldozer driver as she tried to stop a Palestinian family’s home from being obliterated in yet another rapacious piece of land-grabbing). It’s complicated, see. And anyway, perhaps, “History should never be regarded as a zero sum game…the past is mostly far more nuanced than a simple battle between good and evil” (Harmer 2011:255).

At the time of the Gaza Peace Flotilla fiasco conversation erupted on Twitter and in Mark Andrews’ blog provoked by the visit of IATEFL patron David Crystal to speak at the ETAI conference. Some people thought that, given his ‘official’ status in our organisation it was not right for him to speak at an Israeli teachers’ conference. David Crystal himself argued passionately (in conversation), that ‘if I refused to go to places where I disapproved of that country’s governments I would never go anywhere’, and that it is always better to engage in conversation than not to. I found him (as so often) persuasive.

In the end, my invitation to Israel came not because I am a teacher trainer/writer, but because I perform shows with my colleague Steve Bingham, and the British Council in Israel wanted us to perform our show about Charles Dickens there. And though my inclination was to say no (see above), I found that such a position would be (a) too self indulgent, (b) hypocritical for someone who, like David Crystal, has been to countries where I really really disapprove of what the government does there, and (c) a wasted opportunity to understand more – you really DO need to ‘see for yourself’ sometimes. Governments are not the same as people. Teachers and students all over the world are – teachers and students. Two other factors combined to help me make the decision to say yes: I really like doing shows – that’s the selfish one – but/and The British Council has offices in Ramallah too, and maybe, if we did the Israel gig we would get invited there. And so off we went.

And did the shows. They seemed to go really well, especially at the Arab Academic College in Haifa, where (do we flatter ourselves too much here?) two groups of Arab Israeli schoolkids, who joined the teachers and students in the audience, were really bowled over by hearing original Dickens accompanied by Steve Bingham’s wonderful musical artistry. It might have made a difference.

You forget, sometimes, that Israel is 75% Jewish, but that other ethnicities and religions inhabit the compressed region within its (sic) borders. As one taxi driver told us, ‘I am Israeli, I am an Arab, This is my country. The Jews came and took it, but they are nice people I like them’. Another Arab Israeli teacher was less accommodating, saying that by the time they (the Israeli government) had finished annexing all of Jerusalem there would be no chance of a final solution (she used the term unironically).

Guess what! I met some incredibly intelligent, kind, socially conscious and engaging people in Israel. Mostly (but not exclusively) teachers, they were just like other incredibly intelligent, kind, socially conscious and engaging educators I spend my professional life with. Like many other visitors to Tel Aviv, I thought what a great place it would be to live – if you could forget at what price it had been made, and what lengths the country goes to (has to go to?) keep it happy. I met all shades of opinion in Israel: the lunatic rightwing American who told me that the God of Abraham and Isaac was out to get me after I refused to sign a petition to say that Jerusalem should be 100% and only Jewish; the settlement defenders; people steeped in the ‘either them or us’ mentality; but people too, many people, who deplored the wrongs done to Palestinians but who, nevertheless approved of the wall, the ‘green line’, because there have been no bombings since and ‘my children can get the bus to school in peace’; people who only escaped being bombed in restaurants by chance; a mother who was appalled that her son was going into the military because he might end up at the checkpoints humiliating Palestinians ‘but at least it will be him…we have taught him to question everything…rather than some other redneck’ (sic); the young teachers in training worrying (like all teachers in training) how to do their very best for the kids with learning difficulties that they were trying to help.

And what I, as an outsider, mostly learned was that Israel is not/will not go away anytime soon. Whether other people like it or not, Israel IS going to continue to exist. That it is full of ‘us’ too and that some of ‘us’ are pretty good people and some of ‘us’ are nasty thugs. Not much of a revelation I suppose. But the craziness of Israeli politics – a system that ensures no government ever has sufficient power to REALLY do something (like make peace) – the debilitating indoctrination that military service offers (the Arab Israeli taxi driver would never go to the army ‘to kill my brother Arabs, but now they are killing each other! Arabs! It is a crazy world.’), and the impossibility of getting anyone in the region to agree about anything…all that does not provoke much optimism. So what can you do if, like me, you have no power or importance?

The great Jewish musician Daniel Barenboim and the late-lamented Arab Edward Said set up the West Eastern Divan Orchestra, an extraordinary collection of musicians from Israel but also the Arab world – Jewish Israelis and Palestinian (and other Arabs). A great political act? No. Here’s Barenboim talking (in Parallels and Perspectives) about the first time the young musicians met:

“One of the Syrian kids told me he had never met an Israeli before and, for him, an Israeli is somebody who represents a negative example of what can happen to his country and what can happen to the Arab world. The same boy found himself sharing a music stand with an Israeli cellist. They were trying to play the same note, to play with the same dynamic, with the same stroke of the bow, with the same sound, with the same expression. They were trying to do something together. It’s as simple as that. They were trying to do something together, something about which they both cared, about which they were both passionate. Well, having achieved that one note, they already can’t look at each other the same way, because they shared a common experience. And this is what was, really, for me, the important thing about the encounter…..the area we are talking about – the Middle East – is very small. Contact is inevitable. It’s not only dollars and political solutions about borders that are going to be the real test of whether a peaceful settlement will work or not. The real test is how productive this contact will be in the long run, I believe that in cultural matters – with literature and, even better, with music, because it doesn’t have to do with explicit ideas – if we foster this kind of contact, it can only help people feel nearer each other, and this is all.”

And here they are playing the Adagietto from Mahler’s 5th symphony, one of the greatest love songs ever written.

Reference:

Harmer, T (2011) Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War. The University of North Carolina Press

Jeremy Harmer's Blog

- Jeremy Harmer's profile

- 180 followers