Paper

Getting interviewed can be very educational, especially when it's an interview about a work in progress. Before I read a piece of this book at the Monthly Rumpus (see video below), Sona Avakian of the San Francisco Examiner interviewed me by email and asked some questions that got my thoughts turning in new directions: thoughts about the book, somewhat, but mostly thoughts about my relationship to the book. The whole interview is here, complete with fun excursions into other topics (the internet, Joseph Pulitzer, superhero comics). But I like looking at what poured out of me about the book itself.

Getting interviewed can be very educational, especially when it's an interview about a work in progress. Before I read a piece of this book at the Monthly Rumpus (see video below), Sona Avakian of the San Francisco Examiner interviewed me by email and asked some questions that got my thoughts turning in new directions: thoughts about the book, somewhat, but mostly thoughts about my relationship to the book. The whole interview is here, complete with fun excursions into other topics (the internet, Joseph Pulitzer, superhero comics). But I like looking at what poured out of me about the book itself.I told Sona I was going to be reading a passage of the book "about how mass publishing swept over American culture like a flood—or a scourge—in the mid-19th century, and how we're still sort of playing out the culture wars that started in response...specifically about how sexual information was the most alarming part of the flood, and who rose up to fight back against the tide of intimate revelation." And she asked, "How did you get interested in publishing history?" Which I'd never quite asked myself. But I found myself saying this:

"It's kind of a weird route. I spent my thirties as a comic book writer, writing superheroes for Marvel and DC and creating my own odd comics for small publishers, but also writing history and criticism about comics. I'd been a huge comics geek in my teens and into my twenties, and a lot of my work in comics was about seeking my creative roots in old pulp. Marvel Comics basically saved me from depression and despair when I was 13, and for decades I was still intoxicated by the smell of the pulp and the look and feel of that cheap, yellowing paper. Most of the founding fathers of comic books were still around then, and I could go into an almost out-of-body state sitting and listening to their stories of the old days.”

Writing about old comics and pulps always seems to make my prose turn purple, because I followed that with: “I learned my dad had been nursed on the milk of wood pulp too—The Shadow gave him an island in a brutal '30s childhood. And then I ended up writing Shadow comic books, and I had this feeling of a river of four-color ink running down through the 20th century, pumping through the veins of generations of wounded kids.” (My friend Rachel said, "I can't work out whether this is poetical or pretentious." She was being polite.)

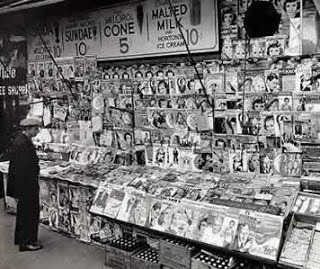

“So when I got out of writing comics I wrote a book called Men of Tomorrow, about the roots of comics in geekdom and sad adolescence and the violence of American life in the immigrant waves and the economic churnings of the past century. But writing that I caught on that comics were just white caps on a bigger wave—cheap paper and ink were a primary carrier of new ideas, information, values, and driving personal fantasies from before the Civil War to the TV era, and still to a great extent up until the Internet took over. Especially for the poor, the young, immigrants, and the adventurously socially mobile, magazines and newspapers both expressed and shaped people's expectations and self-descriptions.

"And there were wars fought over them: circulation wars where people got their heads bashed in and culture wars where people were driven to ruin and suicide or swept from obscurity to power.”

Sona asked what I meant by that last sentence, which is course is what I was hoping for. One thing you learn in comics is how to write hooks. “The first part's simple: In the early 20th Century, battles over newspaper distribution routes and control of corner newsstands were fought by local thugs who killed quite a few of their rivals. The newspapers played a huge role in the formation of organized crime in this country—Lucky Luciano and Dion O'Bannion got their start doing circulation for Hearst before Prohibition made them rich.

“Second part, I'm thinking mainly of two of the big figures in my book: Anthony Comstock, an obscure dry-goods salesman who became one of the most powerful men in American culture—the chief censor of both the federal and New York state governments—through his unrelenting battle against indecent publications in the late 19th century; and Bernarr Macfadden, a professional wrestler and bodybuilder from the Ozarks who became the most successful magazine publisher of the 1920s, and one whose influence is still being felt in mass culture, by fighting back against Comstock with health publications, sex-education books, and finally the genre of confessional and 'true story' magazines, which he basically created."

Then back to the main thread: “I started trying to get my head around that, to understand just how big this subterranean paper ocean had been, and then these past few years it's really been coming home to me that the age of paper is ending, or at least it's changing fundamentally. So I wanted to write a paean to it, and try to open up some partial revelation of what it had been—because, you know, you can't really see how your family's affecting you until you move out, and you can't really get what publishing meant until it's fading away—by looking hard at one part of it that hadn't been looked at very much. But one part that I discovered was really powerful, the way magazines drove this whole culture of talking about our private selves and talking about other people's private selves that we're still moving through."

At that point Sona asked me something that made a light go on: "Do you think paper publishing has hit rock bottom yet? Can we expect a resurgence soon?" I said, "I don't think paper has hit bottom by any means, but I also don't think it will be a quick or simple fall. There will be bumps and twists and surprises on the road down. Print on paper will never go away, because some people will love it and be willing to go to the effort and expense of keeping it alive. I mean, horses aren't extinct, right? But I'm not holding my breath for them to retake their position at the forefront of transportation, either."

She asked what I thought of the Panorama newspaper that McSweeney's published, and I said that I thought "it was really fun. It's exactly the kind of thing that subcultures produce when they're fading out of the mainstream—expensive, resplendent, nostalgic. Festive, not quotidian. Rodeos became show biz and an art form when the horse culture ended."

It hit me then that that's a large part of why I've opened the book wider and have become so energized to write it now: it's the book under the book. It's the story of some of the people in the era of mass print and their impact on the world. But the writing of it is also kind of a private celebration of an era that's now fading enough that we can start to see and describe the whole thing.

Published on April 11, 2010 10:11

No comments have been added yet.

Gerard Jones's Blog

- Gerard Jones's profile

- 21 followers

Gerard Jones isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.