Reviving Delight in Russian Literature

Agnes, my current foster dog, with her copy of War and Peace.

Agnes, my current foster dog, with her copy of War and Peace.2023 was the year of resuming my delight in Russian novels. Nearly fifty years of intermittent longing for a treasured copy of The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky had passed; my first lover had torn and sliced the book into pieces and scattered it around my neighborhood. One day in 2023, I realized the same edition might be available through the internet. It was.

Inviting a powerful object into your life can open a door. Shortly after the replica of my long-lost book arrived, I received an assignment from Foreword Reviews to review the Russian novel A Volga Tale by Guzel Yakhina, and from there came the adventure of writing a longer, hybrid essay/review about A Volga Tale for On the Seawall. From there came learning of the Footnotes and Tangents community’s 2024 slow read of War and Peace, which I’m participating in now.

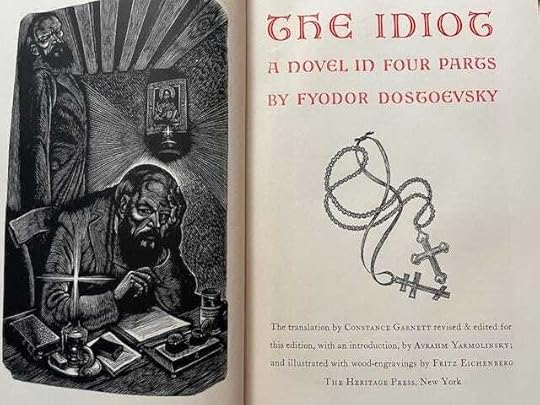

Aside from Nancy Drew mysteries and books about horses, there weren’t a lot of books in my childhood home, but a temporary subscription to a book club brought two new adult novels in. These were hardcovers that came in their own fabric-covered slipcases, which impressed me as classy. One was The Idiot, thick, heavy, and illustrated, a book that when open had a 14- by 10-inch footprint that could be draped across your lap like a small, sad dog. The Idiot’s illustrations, by Fritz Eichenberg, were wood cut prints, dark background and foreground with slashes and streaks of light outlining characters and their settings. The characters’ faces, for the most part, were contorted with emotion, like teenage life.

Title page of The Idiot with wood cut print of a struggling and divided Dostoevsky

Title page of The Idiot with wood cut print of a struggling and divided DostoevskyI first read The Idiot several years before the destruction of my treasured copy. If you’re not familiar with the book, one way to summarize the novel is to say Dostoevsky wanted to write about a “wholly good man.” The novel’s good man, Prince Myshkin, is afflicted with a seizure disorder, not unlike Dostoevsky himself, who became epileptic as an adult.

This is a recurring trope — at least in certain stories — that moral perfection for men comes with injury to the body, or a physical difference from others. Think of the blinded, one-armed, and ethical-at-last Rochester at the end of Jane Eyre. Or, perhaps, Jaime Lannister from Game of Thrones, who loses his hand and briefly subscribes to a moral idea about community. Or Jesus.

When, in 2023, I opened the package with my new copy of The Idiot and slid the book from its classy slipcase, the slipcase came apart. The book itself was in better shape, and its heft brought back the sensation of being immersed in literature and the suffocating weight of a violent love affair. Being underwater feels powerful when I can swim, but frightening when I can’t swim away. But this is the story of reading, the one with a happy ending.

Nostalgia and excitement about something wholly new filled me in 2023 as I read A Volga Tale. The lush and rhythmic English translation by Polly Gannon reminded me of Constance Garnett’s translations of 19th century Russian fiction. Here were the sonic pleasures of subtle meter and rhyme, the roll of language as it meets with thought. Like Dostoevsky’s work, A Volga Tale employs magic realism and is concerned with “the relationship of the country and personality.”

The novel’s central character, Bach, is an ethnic German who lives on the Volga, a descendant of one of the many Germans encouraged to relocate to Russia by Catherine the Great. Bach is a village schoolteacher who loves languages but becomes speechless when he must face the Russian brutality that robs him of his wife and leaves him a daughter, Antje. With Antje, he conducts “a perpetual, gravely serious conversation in the language of breath and gesture and movement. Each of them was like an enormous ear, poised to listen and understand the other.”

Coming across familiar ideas brings the pleasure of recognition, and this can open my mind to new ideas, as if I’m also an enormous ear, poised to listen. What was new to me in Yakhina’s novel was her concern with “the issue of internal freedom and its ratio to the external freedom.” In Dostoevsky’s novels, freedom is sometimes granted through religious faith, but more often, it’s the characters’ own thoughts and actions that free them or shackle them, creating liberating epiphanies or inescapable prisons of remorse.

Yakhina’s outsider status as an ethnic Tatar woman in Russia may have contributed to her insights about the pressures of external freedom or lack thereof on a character’s internal freedom. In the early days of the Bolshevik Revolution depicted in A Volga Tale, the young people of Russia are swept up in a new life of communal effort for the communal good. Bach’s daughter Antje grows strong, happy, and free of gender constrictions with her comrades during that brief, pre-Stalin era.

The young women in The Idiot don’t experience such freedom; the main characters exist at opposite ends of literature’s traditional womanly spectrum: Aglaya Ivanovna, the virgin daughter of a general, and Nastassya Filipovna, an orphan, sold in some vague way to a wealthy man. By the time I read The Idiot, I’d already learned about the two ends of the womanly spectrum from Jane Eyre — the very good, innocent woman (Jane) at one end, and the very bad, experienced woman (Bertha) at the other end.

As is the habit of many readers, after the last page of A Volga Tale, I looked for more books by Guzel Yakhina and found her debut novel, Zuleikha, which is based on her family stories about life under Stalin and in the Siberian gulags. It is a spellbinding, cross-country epic, and because it won numerous literary awards around the world, I was able to get a copy from my local library. I’m hoping that Yakhina’s third book, a historical novel about the 1921 famine in Russia, will be translated into English soon.

In November of 2023, as if reading my mind (or my clicks, which are similar), Substack alerted me about a 2024 slow read of War and Peace. It had been decades since I read that book. Was it a coincidence that the used bookstore in my part of town had a paperback copy of War and Peace in the Constance Garnett translation, the translation I’d read in the 1970’s after The Idiot sent me in search of more Dostoevsky, which took me to the library and The Brothers Karamazov, The Possessed, Crime and Punishment, and later to War and Peace? Is it reckless of me, that with so many books and so little time, I turn to re-reading at least once a year?

Now it’s 2024, and I’m (re)reading a chapter a day of Tolstoy, thanks to an algorithm and to Simon Haisell and his Footnotes and Tangents group. Tolstoy’s words sound both familiar to my ear, and wholly new; I’d forgotten how funny he can be. This may be an even happier year than last year, when the used but new-to-me copy of The Idiot sat on my lap like a small, sad dog. Its pages felt soft, and miraculously whole.