104. What does the data tell us?

My last blog welcomed the setting free of the Office for Place as a new arms-length agency of Government and compared it with the long defunct CABE to which it will inevitably (although perhaps unfairly) be compared. While CABE embraced new technologies, its technologies were that of the internet and the PDF and only tentatively, towards the end of its life, social media. The Office for Place is born into a very different world of big data, AI, and the metaverse, and how it embraces the opportunities and challenges these technologies bring will help to define its legacy.

Data is nothing new

Being aware of this, its inaugural conference – Places at Pace – included a session on ‘What the data tells us?’ Chanuki Seresinhe from Beautiful Places AI and myself were asked to speak.

I started by making the seemingly obvious point that data is nothing new. Designers and planners should always start by understanding the context, and the data that we gather allows us to do just that. The difference today is that more of it is available online and in much greater quantities and detail than ever before: from rich socio-economic information, through social media data, to 3D aerial photography, environmental data, street view, and even live cameras on many streets that we can connect to.

This is both an opportunity and a potential problem. My students always used to go to the site first, and now they go to the internet first. While what they find there can greatly enrich their understanding of places, its remote nature means it is all too easy to forget that we are dealing with real places and real people. And it is those people who will live with the consequences of our actions.

The danger of course is multiplied many times over if it is developers rather than students doing this. But with design time increasingly squeezed on projects, the reality is remote analysis and remote design, and, very soon, AI generated urban design. Tools such as Adobe Firefly can already deliver amazingly convincing (although still conceptually naïve) results.

So, we need a heath warning: online data can be hugely enlightening, but over-reliance on it without truly experiencing and understanding places can be risky! That risk multiplies as we move up in scale from single sites to whole local authority areas, as, for example, will happen when preparing authority-wide design codes.

As I tell my students, to truly understand what works and what does not in urban design, we need to visit places (repeatedly), speak to people, observe them through time and carefully interpret what we see and hear. Then, we can enrich our understanding with what we find online.

A further source of readily harvested data

In addition to first hand and online data, there is another rich source of readily available data for us to harvest. That is the data contained and already analysed in thousands of books and dry academic papers which are hard and time consuming to access, and so are often ignored, although AI is making that much easier. Nevertheless, to help address the problem, a few years ago I built Place Value Wiki which brings together hundreds of robust empirical studies from all around the world which link aspects of place quality with aspects of ‘place value’. In other words, it brings together data on the qualities of places that add value: economically, socially, environmentally and with regard to health outcomes.

This collective evidence tells us a huge amount about the benefits of a well designed built environment, for example that such environments can help to deliver better mental health, lower rates of crime, property uplift and reduced vacancy in commercial real estate, and reduced energy use and associated carbon emissions

No time to explore any of that now, suffice to say that the same evidence also reveals much about the sort of qualities that deliver that collective place value. To crudely summarise:

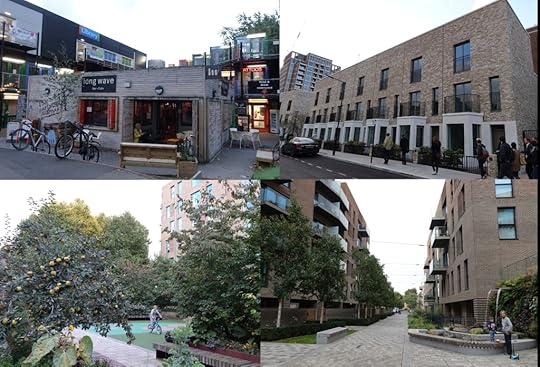

rather than building the sort of places characterised by the first collage of images – sprawling, disconnected, single use, and roads dominated – which delivers short-term profit for the landowner and developer at the expense of the place; the data suggests we should be building the qualities characterised in the second collage – compact, connected, mixed use and green – which delivers long-term place value and still makes a good profit. Places that are bad for us

Places that are bad for us Places that are good for us

Places that are good for usElsewhere I have envisioned this as a ladder of place quality, climbing from qualities we should avoid to those we should require. And what the evidence says is good for us also turns out to be what we say we desire! This was clear in our Home Comforts research conducted in 2020 during the first national lockdown when over 2,500 people across the UK told us that what they really valued were places to live that were green, mixed and walkable (and had room to swing a cat!).

Not rocket science

Now, I hear you say, this is all obvious and nothing that we don’t already know. And I would agree. None of this is rocket science (although the data that underpins the evidence required a lot of science to understand it). So, given that we know all this stuff already, why are we not building more schemes like Goldsmith Street in Norwich and instead spend our time building places like Millers Field, a contemporaneous project just three miles down the road as the crow flies?

Goldsmith Street (above) and Millers Field (below), Norwich

Goldsmith Street (above) and Millers Field (below), NorwichWhat the data doesn’t say

Here we need another health warning – or a whole host of them:

People are perverse. Sometimes they say they like one thing and do something else. They say, for example, that they like streets with nice green front gardens then buy houses with everything pre-tarmacked!Data doesn’t tell us about the necessary trade-offs when shaping places. An infamous MORI survey suggested that bungalows were the British peoples’ favoured house type, but if we all lived in bungalows, we would have no countryside left!Data can easily be manipulated to tell the story we wish to tell. Highways authorities have been doing that for years to perpetuate their traffic first models of design and development.Data doesn’t fully reflect our subjective values. Peckham High Street, for example, would never be identified in any search engine as a beautiful place, but a better example of a rich, vibrant and socially supporting environment, I have yet to find. Peckham, ‘Bruitiful!’Tastes anyway change, as a 19th Century quote from Benjamin Disraeli reveals. He wrote, reflecting on London’s Georgian and Victorian streets that today we so revere: “All those flat, dull, spiritless streets, all resembling each other”.Finally, data doesn’t tell us that still the only way to optimise the place value of any site as a sustainable contextually distinctive place is through a creative design process. AI may yet change that, but it is not there yet.

Peckham, ‘Bruitiful!’Tastes anyway change, as a 19th Century quote from Benjamin Disraeli reveals. He wrote, reflecting on London’s Georgian and Victorian streets that today we so revere: “All those flat, dull, spiritless streets, all resembling each other”.Finally, data doesn’t tell us that still the only way to optimise the place value of any site as a sustainable contextually distinctive place is through a creative design process. AI may yet change that, but it is not there yet.So a final warning. Embrace the data … but beware!

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

Matthew Carmona's Blog

- Matthew Carmona's profile

- 12 followers