Video Art--The Beginnings

Historically, American video art begins in the late Sixties within and around the studios made available at educational stations in Boston, San Francisco, and New York, thanks to charitable grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, the John D. Rockefeller II Fund, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York State Council on the Arts.

Numerous artists came to WGBH (Boston), KQED (San Francisco), and WNET (New York) to explore the gear. What drew them there?

Many entered the new medium primarily because they disliked the limits of some earlier one. With Nam June Paik, for instance, we find a man who mastered all the forms of music available to him and found them all boring. He destroyed the piano, the violin, the opera; what was left? Only when he found an instrument like the TV set could he fulfill himself without merely attacking his artistic fathers.

What general notions of art did people enter video with? The first idea, the first item in their cultural luggage, was the cult of personality. That romantic Western idea that art should somehow be self-expression still held sway, although most contemporary artists are high enough to empty their work of obvious emotionalism. Still, the self became the subject for such wildly different video artists as Vito Acconci, snarling and biting; Nancy Holt, teasing, cherishing, remembering her aunt; Hermine Freed, reenacting, questioning her own baby photos; Lynda Benglis, arousing her own sex. And diary tapes seemed to be almost a phase through which most people go, turning on the camera and letting it run wherever they traveled, like Shigeko Kubota’s Europe on Half Inch a Day and Juan Downey’s very personal tour of Latin America. These tapes reveal exactly how much the person dares to reveal, or cares to; the audience can test the maker’s character, as performer, and as camera aimer. “Art should be original because I am,” runs this theory, at its crudest. Still, we are entitled to ask of each work of video art: How real is this person?

A second notion stemmed from the very multiplicity of media available to any artist. Rich inheritors of the modern capitalist world, many creators took for granted that we could make color film with sound, photographs that could be printed on any surface from plastic to canvas, prints that could run the gamut from Gutenberg to rubber stamp, painting that could jump from Pop to Minimal to eye-popping Op, sculpture that could stand still or jerk around the room, theater that might run out of the theater to create temporary events in the street, music that might include random sounds as part of the score, and network television showing old-fashioned drama alternating with kiddie games plus forties-style movies. Given so many tools, the beginner often felt overwhelmed, but eventually he or she became reconciled to the fact that year by year one had to learn new skills.

An artist moves through a number of media, acquiring each, domesticating each, growing into and outgrowing each. The unity is in the person. This experience leads to a conception that Douglas Davis describes as pursuing one idea through many media. He pounds his hands on the inside of the TV set, then on an inkpad, then on paper. Throughout the sequence the audience can imagine his act. So some artists, like Keith Sonnier, see themselves as the central figure in their work, and they move from one medium to the next, learning it, leaving a record, going on to the next field. Others see their own action as the basic image, to be shown in video, but also in print, or photograph, or map, or text as well. And even those who explore other media do so in order to bring back some technique that will enliven their video, as Bill Etra does when he studies computers. Video is one among many; therefore, it is only a medium. You and your idea pass through many media in a lifetime.

Conscious of the enormous range of media available, many artists have evolved a third general notion: that they should explore the uniqueness of each medium. Each medium does certain things well, other things poorly, the argument runs. The task of the artist is to study the new medium, to find out what it does well, and then to explore those areas fully. Is this something that only video can do? Buoyed by the way in which Sixties artists challenged painting (what is painting?), Nam June Paik toyed around with the actual wiring of his television sets; Richard Serra and Vito Acconci tried communicating within closed-circuit systems; Douglas Davis tested out video cameras, hanging them out of skyscraper windows, burying them in Germany. Reducing TV to mere light levels, flowing electrons, blur, and continuous change, artists have gradually narrowed down the areas that seem uniquely video. It is here that the best art takes place. Not imitation film, but genuine video, not theatrical photographs, but live video. In early video art, the American ideal, it seems, has been to create an intensely personal style as one explores the unique capabilities of video, consciously comparing it with media such as painting, words, or music.

True to their era in another way, video artists also placed a high value on ambiguity and activity. That which is difficult to perceive seems to fascinate us, as we try to bring it into focus. And video is a natural for a people who feel that the act of perception itself involves the act of thought. Rudolf Arnheim, author of Art and Visual Perception, says that certain cognitive operations normally called thinking occur during, not after, perception—simplifying, analyzing, abstracting, synthesizing, correcting, comparing, resolving, recombining, separating, establishing context. The uncertain video screen provokes all these operations, keeping mind and eye occupied continuously, until we decipher “how it is done.” At that moment interest drops off. So sheer activity becomes important. An active artwork is one that changes your perspective on the scene rapidly, showing you new ways of understanding the event, new angles of perception. Instantly replayed, quickly dialed, video changes so fast that it can be made as active as the mind creating the work.

In making an artwork perceptually ambiguous and psychologically active, what choices does an artist have, what tendencies in the medium can he or she exploit? Artists have evolved a rough list of choices that they feel they must make when entering video, decisions thrust on them by the medium, opportunities dictated by our culture and by the nature of the machinery. If we explore these choices, we can see some of the questions confronting each artist as he or she begins to work and each viewer as he or she watches for the first time. In addition, we may arrive at a rough fix on the simmering critical debates alive in video art during the early Seventies.

1. Are the Changes in the Image Primarily Electronic, or Are They Mechanical?When an image changes electronically, we watch a gradual transformation from within, as if the form on screen were growing by itself. But in mechanical changes we flip from one picture to another as in a slide show, each break a complete cut.

Electronically we seem to be following a constant, flowing metamorphosis, as when pools of color seem to belly up, then contract and rearrange themselves. With mechanical change, we have what Shigeko Kubota calls “Stripe, stripe, stripe; cut, cut, cut”—the physical chopping of the videotape into segments, providing strong contrasts, fast jolts.

2. Are the Images Basically Natural, or are They Predominantly Machine-Made?Natural images are humans, plants, animals, landscapes, seen clearly enough to be recognizable; we are discussing the basic image, before any tinkering gets added. Most conventional TV dwells on such imagery, until it comes to commercials, and most video artists go through a video diary period, showing real, if fuzzy, scenes.

Machine-made images are artificial when they start (geometric shapes, computer graphics, highway loops, machinery itself) or gradually turn natural images into abstract ones.

3. Is the Screen Overloaded with Data or Underwhelmed with a Minimum of Audiovisual Information?Few artists inhabit a middle ground. A few tapes provide an absolute minimum of information—Bruce Nauman walking in circles for fifty-six minutes, Nam June Paik showing moonscapes unchanging for hours.

Other tapes tend toward overload; active, even frenetic, they combine many different kinds of images, techniques, colors, speeds, creating a dense thicket of information, like Juan Downey’s multiple reflections on the mirror in a painting by Velásquez.

4. To Edit? Or Not to Edit?Or, really, does the work stress the editing possible with tape, or does it ignore that potential, stressing instead the unbroken accuracy, the actualness of the time?

The unedited tapes come when an artist sets up a camera in an environment to record whatever goes on or when someone like Minimal artist Bruce Nauman deliberately repeats an action, recording it exactly as long as the action takes, such unedited tape may be exhausting to watch, but it gives the effect of reproducing real time accurately.

Edited tape emphasizes the editing itself, as when Hermine Freed intrudes in Art Herstory to comment on her own “unedited” comments, made earlier, during the actual taping.

5. Are We in the Present, with the Video Camera Running Right Now and Each Image Instantaneous, or Are We Supposed to be Aware of Different Time Strata Embedded Within One Tape, Completed in Time Past?The question of time itself becomes a vital one for many artists. Real time means the camera is on right now, and you are seeing what is really going on; the view is actual, contemporaneous, live. Acconci is in the basement right now, threatening you with a pipe; those people on the screen waving are right behind you.

Other time is usually past, but it may suggest a science-fiction future, too; such tapes tend to emphasize multiple times, mostly all past, through editing, through layering, through actual dialogue.

Occasionally an artist like Lynda Benglis in her Now will record complicated real-time interaction with the machine, to give you the feeling of being there right as she does it, yet the very fact of its being just a tape demonstrates that we are actually in the past.

6. How Many People Are Affecting the Image? How Many Get Input?Multiple input would mean that many people can get into the act, as in Allan Kaprow’s Hello, where people all over Boston say hello to each other, Bill Etra’s Astral Projection, in which many musicians end up in the stars, Bruce Nauman’s corridor installation in which the audiences’ backs show up on the screen, Nam June Paik’s synthesizer demonstration, in which your image appears under his manipulation, Douglas Davis’ phone-in marathon called Talk Out.

By contrast, many tapes are made solo, with the communication all one way, from the artist to you, with no chance for feedback, comment, or interplay.

7. How Much Interplay Is There with the Environment?During these early days, the bulk of video art remained on tape, but many artists like Davis and Kaprow tried to reach out of the set into the wider environment. Some did this physically, arranging TV sets in a pyramid in a museum, then showing you different glimpses of life in- or outdoors, stacked up together. Juan Downey put cameras in rows, got people meditating on their own, and showed the pictures to audiences, establishing a temple atmosphere; Nam June Paik distributed sets with ocean images on the floor of the Galeria Bonino, calling it Video Sea; Shigeko Kubota’s Nude Descending a Staircase encased the TV sets in the staircase and showed pictures of a nude descending that staircase.

By contrast, purely tape pieces seem content to remain in the box; they assume the framing device of the TV screen and ignore the immediate surroundings, not including them, not affecting them.

8. Is the Focus on Process or Product?A final decision confronting the artist is whether to hide the labor, displaying only a final product, as in Downey’s mirror of a painting, or to reveal exactly what went on during the making, stressing the process.

Some works suggest that the process is more important than any final version: Nam June Paik’s synthesizer (you step into its range, and you become its subject, yet the machine continues without you when you go), Sonnier’s Animation (he has not edited; we have a half hour of raw outtake from his experimentation, not a polished cartoon, and when an engineer asks, “Do you want to save any of this stuff?” Sonnier saves and shows it all, the whole process).

The artists who lean more toward product hide how their tapes were made, pretending that the art was born fullblown from the forehead of the artist, drawing attention away from the making of video to some other subject.

ChoicesEach choice an artist makes inevitably affects the next, and on any given question the sophisticated artist may tend to mix both techniques within one work, consciously combining opposing extremes.

Artworks that show just one tendency or another may seem pure, but boring. Boringness is not bad, but it tends to generate rage in audiences, no matter how hip.

An active artwork is one in which our view changes fairly rapidly. And the most interesting work often shows us ordinary reality as it undergoes the transformation into a purely machine-made view of the scene.

Several of the best composite half hour tapes alternate sparse segments with overflowing detail, moments open to a general public with soliloquies.

Once we understand the two horns, then, we may enjoy watching the artist dancing back and forth across the dilemmas.

Such considerations also suggest artistic divide in our culture between two general tendencies. As in much contemporary painting, we see a division between stringent “realness” and playful artifice, between hard, if full, information and lush entertainment, between an almost didactic urge to point to mere process and a more old-fashioned aesthetic impulse to create a lasting work.

In video, then, one tendency tips toward realistic pictures of real people, without too much extra information or editing, right at the moment, with as many people as may walk into camera range showing their effect on the immediate environment as an essential part of the piece—stressing that process rather than any afterproduct.

The other tendency tilts toward more artful image, larded with data, carefully edited, hinting at many more periods than just the present, controlled usually by one determined artist working with tape to make a striking final product.

Any given artist must pick and choose elements on both sides of that cultural divide, and the results always depend on personal taste. But in most artists’ careers, there is a movement away from the simple and realistic toward the more artful.

In each of these areas, personal style is decisive. Personal style, to me, is the trace left by intense personal conflict, as Paik’s reaction against traditional music shows up in his fondness for random electrons, and Etra’s feeling that he is eternally a student learning to control the equipment results in the brevity and clarity of his études. Ask all the questions you want of an artist’s work, and you will eventually come up close to the person. Perhaps the growth of an artist is a proper subject for study. Biography is a legitimate part of criticism, and even essential, for it suggests the conflicts that lead up to an individual’s making certain stylistic choices, yea or nay.

When we go beyond particular tapes or installations to size up entire careers, we are weighing a life. Some people—through art—seem striking. Their image startles, amazes, impresses, attracts. Their picture burns in our mind’s eye, ambiguous enough to puzzle, but active enough to keep our attention. Among artists, they are the video pioneers.

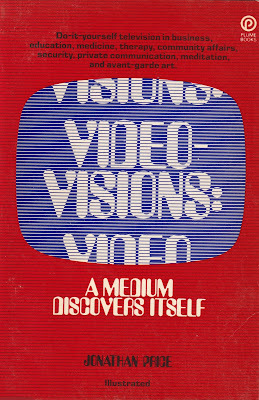

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself. New American Library. 1977.

About JonathanReviewed in Videography, November, 1977; New York Times by Jeff Greenfield, December 18, 1977; Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1978), by John Howell; Leonardo, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer, 1980), by W.H.M Kaiser.

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price