Hermine Freed Gets Into Video

Interview by Jonathan Reeve Price in the book, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself, New American Library, 1977.

“I’m a New Yorker,” says Hermine Freed, one of the most chic of the gallery video makers. “Now if a bum stops me, I’ll give him a quarter and have a little chat.” In fact, she got into video by talking.

“It all started when I was doing a TV program on Channel Thirty-one,” she says as we chat in her high-rise steel-and-glass apartment. “I was the art critic in a book review program, and after doing several of these programs, I was getting very frustrated with the TV medium and how unable they were to manipulate it. I was told to propose a program of my own on art, for Thirty-one, and just at that point, the station lost its budget, and people were being fired all over the place. But I was still writing my proposal. And when I finally went to the station master, he said, ‘I don’t want to read anything else, it’s been a bad year, I want to see it.’ And I thought, super eight and no sound, how am I going to do that? And I remembered some friends who were doing video, and I called them, and they came by.

I was in East Hampton at the time, so the natural thing to do was what was in the neighborhood, so I did Jim Rosenquist, Alfonso Osorio, who lived next door to me. And I was hooked, once I had touched that video camera and saw what it could do.”

What struck her right off was the difference between carrying a portable video camera into somebody’s house and walking in with an entire conventional TV crew. “I could never do on TV what I did on video. I could never walk through somebody’s property very unself-consciously, without them being aware of the camera. I could never just let them be what they were, paint their pictures, do their things.”

She went to Roy Lichtenstein and settled in. “I was using video for one reason, because it was—unlike film—a medium that could capture reality. The anecdote for this is Lichtenstein.

I spent a few days, he was painting, I was there, he doesn’t care, and then after we were finished, he said, ‘You know, Barbara Rose came by with a film crew the other day, and they had me pose in front of the canvas with a dry brush. You didn’t do that.’

So I said, ‘Naw, I sure didn’t.’ So that was one of the first things that excited me about the medium. But of course, the more you use any medium, the more you become aware of the fact that this truth is not true either.”

Looking back at one of those early tapes, Lichtenstein’s Still Life (1972), I find it organized, edited, and arranged like an essay. The shape is verbal. “Your early pictures were cartoons,” Freed says, and Lichtenstein replies, “I was interested in inexpensive reproductions.”

He talks of dots, halftone colors, and Freed, sitting at the other end of a wicker sofa, asks about “Portrait of Madame Cézanne,” and Lichtenstein’s diagrammatic painting appears. That was his first imitation of another artist, and it was quickly followed by his fake Picassos—Lichtenstein hopes his become genuinely simpleminded. He rearranges his hair.

“Do you look for your images, or do you find them?” she asks. Both, he implies. We see talking heads, then the two figures on the sofa, an informal interview exactly like regular TV, down to the insets of still lifes.

Finally, we switch to him filling in a broad area of canvas as he goes on talking, saying, “I don’t particularly want it to look subtle.”

Red, yellow, blue, and black are his main colors, but this tape is in black and white; he has forgone his trademark dots for crosshatching, arguing for simple shticks. He has a white bowl outlined—sparks of white will show through.

He wants forms that are easy to reproduce, and these show up well on the tube. Where the first half of this tape imitated conventional TV as closely as Lichtenstein aped comic strips, this section in the studio imitates old film visits with the artist.

I enjoy watching his hand running smoothly down the canvas as he talks of mechanically producing the textured area next to his freehand stroke. “I just alternated pieces of tape.” At this point, Lichtenstein knows more about painting than Freed does about video: this tape ends by being a comment, not art in itself.

Still, there was the feeling of casual immediacy. “Of course, this business of immediacy. I love the medium because of my own temperament. You can use it the way you use paint. I love the fact that I can record it, play it back, see what it looks like, do it over again, change it, without having to send it out to be processed, wait two weeks. I usually find that when I have something I’m thinking about, I have to deal with it now; if I let it go two weeks, the immediacy of my feelings goes.”

From immediacy she moved toward artistic questioning of the video truth. “At that point there were artists using video, but not many. We’re now around 1971–2, it’s only three years ago, now that I think about it [summer 1974], but it seems like a million years, because at that point there was no video being shown anywhere.

Bruce Nauman had made some tapes. I don’t think I was aware of what he had done. Anyway, for a thousand and one reasons I wanted to just make tapes. The more I was making tapes, the more I wanted to make tapes and use them to make art. They seemed to solve a lot of extra-aesthetic problems, as well as some aesthetic ones. So the first tapes I made were tapes that seemed to deal with that medium in an art context.

“The very very first tape was called I Don’t Know What You Mean, and it was a collage of images that were ambiguous as far as quote reality is concerned; it was really a tape about illusion versus reality and the ability of the video camera to see things that the eye doesn’t see or to make images that have an existence of their own.

And all of the tapes, in that sense, have dealt with the line between subjective and objective experience. The one thing that I found the video camera doing that excited me the most was that it objectified the self. If I were recording this conversation on video and then were to play it back, I would see myself removed from the feelings that I have right now. So I would see me as you see me rather than the way I see me.”

Objective one moment (seeing yourself as others see you), subjective the next (going on camera again, to make some more tape), you can be in and out of your body five times a minute. In Two Faces she has one side of her face look at the other side. “The resulting image was me looking at myself. The activity of the tape is me reacting to myself physically, turning, shaking my head, rubbing noses with myself, and kissing myself.” This narcissism, like that of Louise Etra, Lynda Benglis, and Joan Jonas, seems inspired by the unique privacy and publicity of video. But it also stems from the speed of video.

“The electronics of video! Just the fact, you saw my Two Faces thing, you could not with film have that, oneself responding to oneself, kissing themselves, with one side of the face, and then the other side of the face, responding to oneself in that kind of way, the way you can supervise real time on video. It’s that ability to take contemporaneous time—two things happening at the same time.”

We see her name, hear clicks, then see half her face staring at us, reproduced three times to our right; she turns around; the mirrors are reduced to two, then one; she revolves again as hums come into the sound track.

Now, slowly, she leans into the center of the screen, trades heads, rises back up, as her mound of hair separates. We have front on one side, back on the other—faster and faster—shaking her hair. The feeling reminds me of two frames of a kaleidoscope fitting together; arms up, she smiles, leans into the mirror, and gives her image an Eskimo kiss, nose to nose. Then tongue tips.

She wiggles, trying to figure out how to manage a real kiss, succeeds, bends the other way, smiles equally, pats herself, and nibbles like a fish, shares tongues, regards her target with seriousness, returns to the gray, squeezing her nose, caressing hair; her double becomes a ghost, her black being the mimic’s white.

The translucent figure intrudes into her own head, puzzling her; then she absorbs the ghost and stares at us head-on, tucking away a strand of eerie hair. This is video play; she grins and is gone. Huzzah, a Narcissa immersed in her mandala-like pool, mirroring her own doubleness, recovering unity with a twist of the knob.

Reflecting on her newly chosen medium, Freed began to discern two reasons why artists and critics were so dubious about video. One was the false association with conventional TV and its commercial tawdriness. Second was the inevitable tie-in with kinetic art, the high-technology fun-and-games style that had more to do with machines on vacation than art. “It is ironic that artists have been concerned with movement since The Nude Descending the Staircase, but as soon as art really does move, it becomes another form entirely. We cannot look at a videotape in the same way that we would look at a painting or a sculpture.”

Casting about for some frame of reference, she found Abstract Expressionism. “Just as minimalism eschews the personal, video and abstract expressionism are rooted in it. Just as minimalism denies the importance of process, abstract expressionism and video rely on it. Just as minimalism avoids psychological incidents, abstract expressionism and video embrace them. Just as space is concrete in minimalist sculpture, it is elusive in both abstract expressionism and video.” She justifies a comparison with painting since video occurs within a still frame, a flat surface. And she stresses the “objectification of self” as typical of video, the psychological feedback, the real-time response to self, mentioning Peter Campus, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Lynda Benglis. They all “question the possibility of arriving at objective perception."

"Nancy Holt’s tapes allude to the impossibility of isolating experience that is also found in a great deal of abstract expressionist painting. In most abstract expressionist paintings, form and gesture extend beyond the framing edge of the canvas, suggesting boundlessness. . . . when the total image is revealed at the end of Holt’s tapes, it is still a mere fragment of a larger view from which it was taken.”

Most striking for her was the emphasis on process. “Rarely is a videotape totally scripted and rehearsed before it is taped. One quality of the medium which differentiates it from film is the greater possibility of spontaneity. Often in the process of recording a videotape, ideas suggest themselves which had not been a part of the original plan. Video is organic; it can be replayed immediately, and reworked. It is possible to erase or tape over unwanted segments and to redo edits until they work. In this sense, it is closer to the process of painting an abstract expressionist work.”

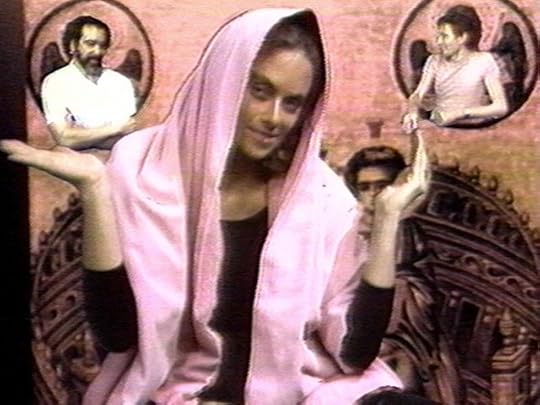

In Art Herstory, Freed recapitulates art history using paintings of women. She inserts herself into each, as the model.

Sometimes the sound is live, from the recording session; sometimes it is a voice-over, expressing an afterthought that raises questions of time and process.

“The sequence of images on this tape is different from that in which they were made.” She is dressed in a shawl. We hear an open mike: “Stand by to cover up. OK, it’s time to disappear. I can’t see either one of you. Give me your hand, Brucie.” A small figure lifts an arm. She reflects: “Might I have altered history to squeeze in an image . . . to fit my needs?” Bruce Kurtz complains, “But I feel like a midget next to you.” She replies, still looking angelic, “You damn well better be.” Next we see her in the middle of a cutout; she lifts her foot. “I’m trying so hard to fly.” Someone hands her a video camera. Meanwhile, the voice-over asks, “Is one of these women more real or more an idealization for me?” Now she sits with a shawl in a nineteenth-century pose, fiddling with video cable, instead of thread. “Some of the women that I’m portraying I wouldn’t want to be. But this is one I wouldn’t mind being.” (Madame Récamier.) She adds, “Even a portrait is theater.” How self-conscious, how bitchy, how true. Then we have Odalisque, the nude women in the Turkish bath. She is nude, back to us, against the painting blown up. She calls out to the unmoving painted figures, as if they were her cast, “OK, girls, hold those poses.” She pats a body, and the voice-over says, “I can identify more clearly with the events of the past now. Time is catching up.”

She does Renoir, Van Gogh (she ad-libs, “Zee chickens, they have not been fed, zis book, she is not very interesting”), Gauguin (“Can’t you ever help with the kids around the house—paint, paint—my neck hurts, Paul”), Duchamp (“Much time has gone by since the first day”), Miro (“I was surprised to find all the icons, a rosary, a priest”), finally Warhol’s Marilyn (“I like the way I look”).

Her features shoot through time, erased, cosmeticized, dressed up, undressed, sometimes close to the original, sometimes wildly far. She is deliberately anachronistic—poking the video camera around the seraglio. She shifts our reality every few seconds: one moment in the scene, one in the studio making the picture, one afterward thinking about it all. Time dissolves under her humorous assault, and the tape itself becomes the only present.

In Family Album, Freed explores her own photographs, commenting, “Childhood seems like a sad time to me.” She shows the pictures to friends from age five, and they laugh together. “I remember wondering if my own child would be like me,” she adds, showing a picture of her pregnant, then of herself as a child. “I remember thinking that grown-ups were right.” Then, through video tricks, she shows the grown-up people right where they were in the photographs from childhood, and they all talk about it. “Can I change the future by remembering the past?”

Freed is full of questions. She tells us what she was feeling when the pictures were taken (“Betty, why are you so mean to me?”), then flashes forward to the present (“I don’t remember babyhood much anymore. I don’t remember when Daddy and I started fighting”).

Best moment: She is smiling at another girl at a prom. Now she can say what she felt: “Hope you spill the punch all over your pretty dress.” This is a real reel reexamination, expressing what was smoothed over before, in life and in portraits.

The courage to use her own life, the questioning attitude, the boldness of her honest anger, the humor are very much hers. Direct, yet perplexing, engaging, witty, and sensual, the style of this piece answers her last question: “What is me anyway?

--Jonathan Reeve Price

Excerpt from Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself, New American Library, 1977

For more:

Freed, Hermine, "Video and Abstract Expressionism", Arts Magazine, Vol. 49, No. 4, December 1974

Freed, Hermine. “In Time, Of Time.” Arts Magazine (June 1975): 82-84.

Freed, Hermine. "Where do we come from? Where are we? Where are we going?". In Ira Schneider & Beryl Korot. Video Art: An Anthology (1st ed.). New York:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1976 ISBN 9780151936328.

Freed, Hermine, "Correspondence," in Vasulka archive, http://www.vasulka.org/archive/Artists2/Freed/

Videos available at https://www.vdb.org/artists/hermine-freed

About Hermine Freed:

Braff, Phyllis "Blending Media and Memory In Punchy, Original Ways", The New York Times, (June 14, 1998).

"Hermine Freed", Landmarks. 2017-08-16.

"Hermine Freed | Video Data Bank".

About Jonathan

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price