An Interview with Author Katherine Reay

This month we had the honour of interviewing bestselling author Katherine Reay, as we featured her historical novel, The Berlin Letters, in our online book club:The Berlin Letters tells the story of a German family torn apart by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. The turmoil that follows: family separation, communist oppression, distrust, espionage, interrogation and prison time all combine in a powerful story that pulls us into the history of that era. Reading this novel has been a fascinating way to travel Germany through books!

This month we had the honour of interviewing bestselling author Katherine Reay, as we featured her historical novel, The Berlin Letters, in our online book club:The Berlin Letters tells the story of a German family torn apart by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. The turmoil that follows: family separation, communist oppression, distrust, espionage, interrogation and prison time all combine in a powerful story that pulls us into the history of that era. Reading this novel has been a fascinating way to travel Germany through books!CHRISTINE FROM FLY-BY-NIGHT PRESS: Thank, you, Katherine, for joining us! How did you begin writing? What genres have you explored, and which do you enjoy best?

KATHERINE REAY: Thank you so much for having me here today and for reading The Berlin Letters!

I began writing in 2009 after an injury. During my recovery time, I read a ton of books and one day a fully formed story came to me. It was that dramatic. But, of course, the writing didn’t happen so fast. That took a couple years, but that initial story became, in 2013, my debut novel, Dear Mr. Knightley.

I read across all genres and there are very few I dislike. I will confess, however, I’m a little too squeamish for horror. In terms of writing, I have published in contemporary fiction, nonfiction, and now historical fiction. I suppose it’s a little unusual to cross three genres, but I have loved it. I have relished exploring stories from a variety of angles and tackling the unique challenges each genre brings. That said, I believe I’ll stick to historical fiction — at least for a few more books.

•

FBN: The Berlin Letters addresses an interesting topic of history: the erection of the Berlin Wall its effect on those living in East Berlin during the Cold War. What first interested you in writing about Germany, and this part of German history in particular?

KR: While researching my previous book, A Shadow in Moscow, the Berlin Wall only received a singular mention as that book stays very focused on the USSR and the United States. But it struck me that, of all the events that happened during the Cold War, the time’s most iconic symbol remains the Wall. I became intrigued by using it both as the structure of a story and as a character within it. The Berlin Letters begins the day the Wall goes up and ends the night it fell. It was truly a fascinating time in both Germany’s history, as well as world history.

•

FBN: The Berlin Letters follows the experiences of a CIA code breaker, Luisa Voekler. I was impressed with your understanding of coding for espionage and how it has been used by intelligence agencies in both America and Germany. How did you come to understand so much about this field?

KR: I studied many books about codes, codebreaking, and espionage — and I found it all fascinating. I had done a little of the research for both The London House and for A Shadow in Moscow, but for The Berlin Letters, I took that research a little farther and learned how to write codes. I wanted readers to be able to dig the codes out of the letters Haris wrote just as Luisa could. I also didn’t use any AI, because — of course — there was none back in the 1940s when Luisa’s grandfather begins coding nor was there in any the 1960s when Haris begins. And I’m so glad I didn’t as creating all those codes was an incredibly fun and rewarding part of the writing process.

FBN: In the prologue, Monica Voekler throws her baby (Luisa) over the barbed wire that is soon to be replaced by the Berlin Wall. This act of immense courage, love and self-sacrifice underpins the entire book and provides a powerful emotional struggle for the main characters. Were you inspired by any similar accounts of this type of bravery, either in that setting or another one?

KR: I am sure they are easy to find, as I found them by simply searching the Internet, but there are two photographs (above) taken on the Wall’s first morning, August 13, 1961, that inspired Luisa’s journey. In the first photograph, you see a woman holding her young son up next to the barbed wire. In the next picture, you see the boy standing next to his father across the barbed wire and the married couple holds hands as if saying goodbye. The wife passed her son to her husband — and if she ever got to hug her son or her husband again, the earliest moment would have been two and half years later when the East German government allowed West Berlin citizens to cross the Wall for a single visiting day. They, of course, wouldn’t have been truly reunited for 28 years until the Wall came down on November 9, 1989.

I read so many stories like that — and there are more all throughout history of the extraordinary sacrifices people make for those they love.

•

FBN: I enjoyed reading depth in your characters. Many of them embody both strength and weakness, good and evil. Some carry deep secrets which, when revealed, change our view of them: Peter and Helene Sauer, Luisa’s grandparents and aunt Alice are all good examples of this. Other characters change greatly over time, gaining wisdom through experience: Haris, Manfred, and even Luisa herself. What process do you use to build your characters? Do you intentionally incorporate this complex, yet lifelike, dichotomy?

KR: Thank you. I really enjoy creating multi-faceted characters and I truly believe — barring some startling examples in history — that very very few people are all good or all bad. We carry a mixture of both within us and, oftentimes, when we work to understand each other, we can better accept or at least forgive foibles, mistakes, poor choices, and the like. I also believe perspective and the subjective nature of our time, place, and beliefs form how we see the world, and even how we’ll behave in many circumstances. It is so easy from our vantage point to look at someone in East Berlin during that time — and I’ll just use a hypothetical here so as not to give anything or anyone in the novel away — and say it was wrong to spy on one’s neighbors for the Stasi. Objectively that is true. But when one considers the pressure, the threats, the arrests and torture, and so much more, that quick answer, while perhaps still true, takes on greater difficulty. I read hundreds of true stories and peeked into some Stasi files and I can say that to withstand their pressure for compliance would have taken great fortitude. And to right about that struggle, with characters landing on both sides of the answer, made for a dynamic and interesting experience.

•

FBN: I was very intrigued by the use of the Ostpunk music/political movement in your plot, and especially that you chose punk dress as Luisa’s disguise to enter East Berlin. How did you come to learn about these real-life punk rebels, and what inspired you to use them in this story?

KR: That was such a great find! Punk, all underground music, played such a different role in the East than in the West. Behind the Wall, it was truly subversive and dangerous — it could get you arrested, and it often did. But those kids, with real bravery, employed their dress and music as a way to defy the regime with some powerful results. Using it within the story not only allowed me to get Luisa across the Wall in an interesting disguise, but give a nod to the sacrifices some of those kids made. I say “kids” because I am old enough to have been their mothers at the time they were active back then. Most of my research for that aspect of the story came from two books: Burning Down the Haus by Tim Mohr and Berlin Calling by Paul Hockenos.

•

FBN: When you visited Berlin in 2023, where did you go for writing research? What did you learn there, and more especially, what was a surprise to discover?

KR: I spent six days racing around the city much as Luisa does in the novel. I visited the Stasi Museum, Checkpoint Charlie, the Gestapo museum, the Berlin Wall Museum, the Church of Reconciliation, the train stations — everything. I ran across Alexanderplatz to experience it as she would, and I raced up the Friedrichstrasse Station stairs.

What surprised me the most, however, was how the visit added texture to the novel. I spent an amazing afternoon with an East German history professor and he shared details with me that I would never have noticed on my own nor could I have found them in books. For instance, as we walked through the eastern sections of the city, he pointed out the “doors to no where.” They are doors in the walls of bombed out buildings, still there, five and six stories above the ground. They are historical and haunting — and were perfect for the story. There are so many examples of touchpoint like that which came to being from my visit.

FBN: The Berlin Letters is a German Cold War novel, but you’ve also written one about espionage in Russia during the Cold War called A Shadow in Moscow. What commonalities have you found between the experiences of East Germans and Russians during that time period? What strikes you as different between their experiences?

KR: There are so many commonalities, but I think the most striking is that both countries are filled with people who believe in the ideology and so many who fight against it — and the tensions on both sides play out in every sector of life, even the bedrooms. Both those novels focus on people, primarily my female protagonists, who search for truth, freedom, self-determination, and wholeness for themself and their loved ones, and some of that is difficult to find within a dictatorship and sacrifices must be made.

As for differences, East Germany, while a country in-and-of itself, was also a satellite of the USSR. To me, there is a nuanced difference between looking to your own leader, and either agreeing and disagreeing with them, and knowing that all final decisions are made outside your borders and imposed upon you. Or maybe that’s not so nuanced, after all.

•

FBN: Who is The Berlin Letters intended for, and what do you hope they will gain by reading it?

KR: Such a tough question as I hope a broad spectrum of readers will pick it up and enjoy it. It’s a spy novel, a family saga, a love story, a story of sacrifice, codes, punk, and a Wall. It’s a story of forgiveness and redemption, of making new choices, and of understanding our pasts. I hope anyone who picks it up has a fantastic time dipping into history — the novel is packed with real events — and is inspired to learn more. I also hope readers walk away with that lifting feeling of hope themselves. New beginnings and new understandings are only a heartbeat away.

About the Author

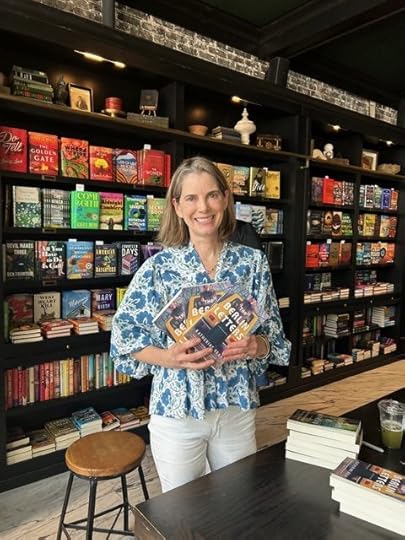

About the AuthorKatherine Reay is a national bestselling and award-winning author of several novels, including A SHADOW IN MOSCOW and her recent release, THE BERLIN LETTERS, a Cold War spy novel, inspired by the Berlin Wall and the women who served in the CIA’s Venona Project, which was recently picked as a NPR “Must Read.”

When not writing, Katherine hosts the What the Dickens Book Club on Facebook and weekly chats with authors and booksellers at The 10 Minute Book Talk on Instagram. But if she’s really lucky, you’ll find her fly fishing and hiking in Montana. You can meet Katherine at www.katherinereay.com or on Facebook: KatherineReayBooks, Twitter: @katherine_reay and Instagram: @katherinereay

Enjoy More Historical Fiction from the Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras: