Writing a Poem

I was thinking about what is hardest to write, and I ranked the various things I write from easiest to hardest: essays, stories, poems.

In terms of word count, poems are definitely the hardest and most time-consuming. Yesterday, I spent an entire day working on a poem, one I had already spent several days working on. It just would not come right. When a poem does not come right, it feels as though you’ve been bitten by an insect, and the bite is itching and itching. You keep scratching, but it does not bring relief. Every time you think the itching has stopped, it starts up again. And then, when the poem does come right, it feels as though you’ve finally discovered Calamine lotion, and it’s actually working. There’s a sense, not of joy or fulfillment, but of relief. Finally, you think. The damn thing is done. At that point, you’re angry with the poem for even existing. What began with a sense of delight has become a source of annoyance. You tell the poem, if it weren’t for you taking up so much time, I could be writing a novel and becoming a famous novelist, or a great novelist, or a rich novelist — or all three, like Charles Dickens. But no, here I am working and working on a poem that probably ten people will read . . .

Poetry sucks.

On the other hand, I must love it or I would not write it. And I do. Poetry is the only thing I write that feels as though it could achieve a kind of artistic perfection. A completed vision. I often tell students, only poetry is capable of being perfect, and only one poem has ever actually been perfect (John Keats’s “Ode to Autumn”), so there is no point in trying to write a perfect story or a perfect novel. It’s just not going to happen.

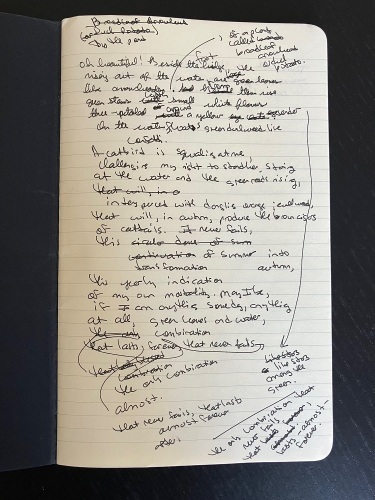

Would you like to see what my poetic process looks like? If not, you can stop reading now . . . But if you want to see, I’ll show you. Recently, I wrote a poem that annoyed me very much. I wrote the first draft back in September, with a pen in the notebook I carry around in my purse, standing on the footbridge described in the poem and looking at the leaves growing up from the water below. I didn’t know what the leaves were, so I did an internet search on my cell phone, and they turned out to be broadleaf arrowhead leaves. Then, I wrote a poem about them. It looked like this:

Then I did not do anything for a while. I was in Boston and there was just so much I needed to accomplish before I could come to Budapest. But of course I brought the notebook with me. Finally, after dealing with a plumbing problem in Budapest (a broken pipe in the apartment above mine), I had time to write. I typed up the poem, revising as I did so. At that point it looked like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge,

rising out of the water, are the large green leaves

like arrowheads, of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead

or duck potato. From among them rise

green stems with clusters of white flowers,

three-petaled around a yellow center, as though stars

were scattered among the green. And on the water floats

green duckweed like confetti. A catbird

is squawking at me, challenging my right to stand here,

staring at the water and the green reeds,

interspersed with dangling orange jewelweed,

of bulrushes rising behind the arrowheads,

with their own stems, taller and a darker green,

that will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

It never fails, the yearly transformation

of summer into autumn, that annual reminder

of my own mortality. May I be,

if I am anything someday, anything at all,

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

And I felt that terrible itching. I had words, even some of the right words, but they weren’t in the right order. They didn’t have the right rhythm. They hadn’t found their proper places yet, and I was missing some words — I was sure I was missing some words. I would need to learn more about the broadleaf arrowhead. So I did some research — yes, I did research for a poem. Honestly, this poem could come with a bibliography! At some point, I was going to include information about how the broadleaf arrowhead was also called the wapato, which is a word the native Chinook used to mean “potato” when speaking with French and English traders. It’s not a Chinook word, but a jargon word they used because the traders could not speak proper Chinook. (I learned that “jargon” is a linguistic term meaning an “occupation-specific language.”) That went into the poem and came out of the poem because it just didn’t fit. It made the poem sound like a middle school history report.

When I tried to describe the broadleaf arrowhead itself, I needed other words I didn’t know, words like “scape,” “raceme,” “inflorescence.” I needed to know that “whorl” is a technical term in botany. I put things in, took things out, moved things around. It all became rather complicated. Somewhere along the way, I realized that the poem was mostly in a sort of rough iambic pentameter, and I thought, why don’t I commit to the meter? At that point, I almost gave up and deleted the whole thing. This was about a week after I had initially typed it, and I had returned to it over and over, as I had time, obsessively trying to get it right.

Finally, it looked right to me, and I posted it. And then I thought, wait, there are just a few things I could fix . . . So I fixed them. Somewhere in that process, I realized the second stanza had eight lines and the first stanza had fifteen lines, which didn’t feel right. So I added a line to the first stanza. Eight and sixteen just felt better . . . It’s such a strange process, mostly of intuition. But at the same time, I was constructing something, and it needed to be structurally right. It needed to have sixteen lines, then eight lines, and to be in a kind of iambic pentameter (if you don’t look too closely).

And now the poem looks like this:

The Broadleaf Arrowhead (or Duck-Potato)

Oh beautiful! Beside the footbridge, growing

out of the water, are the large green leaves

of a plant called broadleaf arrowhead or duck-potato.

Among them, from the water, rise green stems

called scapes, along which grow its small white flowers,

each with three petals around the yellow stamens,

arranged in whorls along a central raceme

and clustered in a pattern called inflorescence,

like stars against the green. Beneath them float

lenticular leaves of duckweed, like confetti.

An angry catbird is squawking from its perch

among the bulrushes, as though to challenge

my presence in this tangle of summer foliage —

the arrowheads, the dangling orange jewelweed,

the rushes whose stalks, rising from tall green blades,

will, in autumn, produce brown cigars of cattails.

They remind me of the annual transformation

of summer into autumn, and of course,

inevitably, because I am only human,

my own mortality. May I become,

someday, if I am anything, anything at all,

this, right here, despite the annoying catbird —

green leaves and water, the only combination

that never fails, that lasts almost forever.

I don’t know if it’s any good, but it’s finally what it wanted to be, or I wanted it to be, or Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, wanted it to be. I don’t know who wanted the poem to be this way, but it finally feels finished. It finally feels like Calamine lotion . . .

So that’s it, that’s my poetic process. I honestly don’t know why I write poetry, except that it does something good to my brain — my brain feels right afterward. It feels as though it’s been used to do what it was designed for. That won’t make me a rich, famous writer, and it may never make me a great one, but it probably makes me a better one. I hope.