Non-fiction that makes you feel (with Mini Grey)

Non-fiction books are sometimes seen as factual, and not emotional. ButI think this is far from the truth, and in this post I’m going to have a lookat a few non-fiction books, and consider how they make us feel.

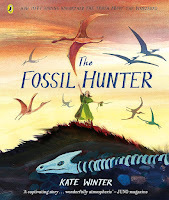

The KlausFlugge Prize is awarded to debut picture book illustrators. Winning an awardlike this is exactly the spotlight you need when you’re just starting inpicture books. A non-fiction book had never won before, but this year it did,with Kate Winter’s The Fossil Hunter. It’s the story of Mary Anning. Andit shows that a non-fiction book can have powerful visual story-telling.

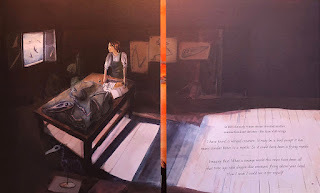

I was lucky enough to have achat with Kate at an online event with the brilliant Just Imagine. She showed us the sketches of Mary that hadguided her making of the story. Mary often is holding a light, and I think Marylooking hard and shining a light into the past might be an important theme ofthe book.

A Mary Anning sketch by Kate Winter

A Mary Anning sketch by Kate Winter Another sketch by Kate

Another sketch by Kate

To me, the illustrations in The Fossil Hunter are about capturing the lightand the moment and the feel – of what Mary Anning is experiencing.

There’s a looseness in the style of the pictures – they’re not toodetailed, not pinned down, gestural, slightly unresolved – so that yourimagination has space to fill in.

Work-in-progress stages by Kate of an image from The Fossil Hunter

Work-in-progress stages by Kate of an image from The Fossil Hunter

If these pictures were more photographic, more realistic – we wouldn’thave that space to project onto them. The figure of Mary is often the onlywoman – alone, resolute, but also looking into a vivid vanished world.

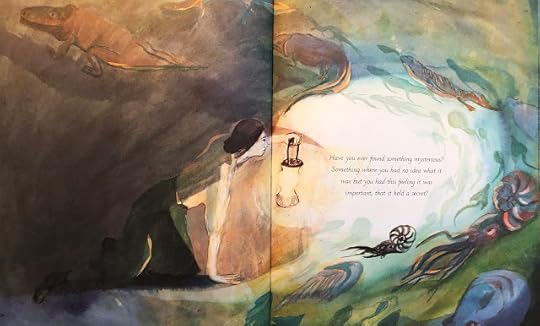

Scattered through The Fossil Hunter are gatefold pages. The gatefold isan opening to a whole new world hidden beneath. Under the gatefold there’s ahidden layer, waiting to be discovered.

Sometimes the gatefold is a door into past worlds that are an explosionof colour, with Mary exploring.

The gatefold is a way tophysically dip into the past, into a layer of parallel worlds, as Mary imaginesthe past, millions of years ago.

It’s also away to open a book of wonder, a cabinet of treasures.

Sometimes fossils in shale can be like treasures hidden within the leavesof a black book, waiting for you to be the first creature to see them sincethey were buried in the mud, millions of years ago.

Here is Mary gazing into the unknown, again with her light to seefurther, to uncover secrets. The pictures are enabling us to feel Mary’swonder.

In Rob and Tom Sears’s book The Biggest Footprint, all of humanitygets smooshed into one giant human, 3 kmhigh.

They said about making it: “We started out with a weird thought experiment:what if, instead of 8 billion humans, there was justone, colossal mega human, smooshed together from all of our mass? How big wouldwe be? What would we be like, and what sort of mischief would we get up to?”

This book is about getting anidea of the scale of our impact on the planet. Numbers in the millions arereally hard for us humans to get our heads round, but this book tries topresent this visually, comparing numbers and sizes, always with something shownfor scale, so we can start to build the perspective to see what we’re up to asa species.

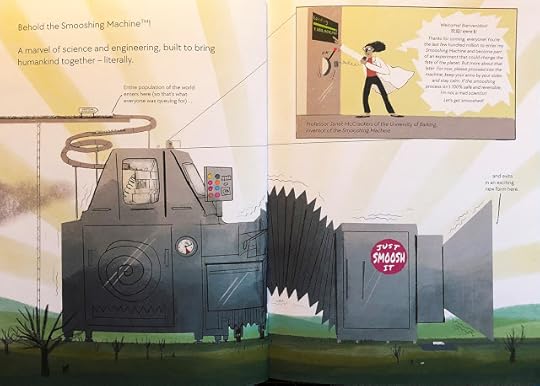

At the start there’s a huge crowd of 8 billion people – what are they queuing for? It turns out, it’s to go inthe smooshing machine.

And what comes out of thesmooshing is a huge blue bemused mega-human.

The mega-human isn’t deliberately bad, but it’s clumsy and not reallyaware of how powerful it is.

For scale, all the wild tigers there are in the world (less than 4000) get smooshed into a 44 metretiger. It bounds out of the smooshing machine, a stripey flash, looking prettybig perched on the Taj Mahal…

...but then it fits easily on the thumbnail of themegahuman.

...but then it fits easily on the thumbnail of themegahuman.

We get to compare the 3 kmheight of the megahuman with the smooshed mega giraffe (size: up to the ankle) Theunbelievable scale of what we’ve done to our planet in the last 100 years is shown by the changing sizes of the mega-animals.

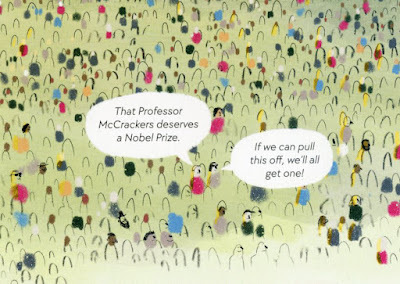

Finally our mega-human meetsall-the-humans-who-have-ever-lived, and then a mega-creature who is All-Life-On-Earth,both of them increasingly enormous – but not as big as the monstrous ball thatis Everything-On-Earth-Made-By-Humans. And now I’m feeling dizzy with theperspective – the human-made world is now more massive than the living one.

In this picture the small figure talking is All-The-Humans-Who-Have-Ever-Lived, the Mega-human is the teeny blue blob to the left of them.

In this picture the small figure talking is All-The-Humans-Who-Have-Ever-Lived, the Mega-human is the teeny blue blob to the left of them.The scale of our impact is incredible. The people of Earth are producingstuff (concrete, metal, tarmac etc) every week that is equal to theircollective bodyweight.

In these final spreads all the people of Earth have been de-smooshed – (thiscould have been a good gatefold!) How it makes us feel is an important factor –we’ve been included in the smooshing process, we’ve been taken on a tour of thescale of life on Earth and the scale of human impacts, we’ve been shown how wecould turn ourselves around, and we’ve been released from being smooshed to beindividuals who feel part of something with immense power – and what if thewhole of humanity got a Nobel Prize for turning the fate of the Earth around? Maybewe feel a bit of hope.

Tom and RobSears said:

“It is easy to feel hopeless. We tend to reason that the individualchanges we can make are tiny compared to the scale of the crisis. Well, thatmay be true! But the lesson of the mega human is that when we act together we dohave immense power, power to do both harm and good.

As 21stcentury individualists, it can be hard for us to accept the idea that being asmall part of something powerful ‘counts’ as real power. We’re fixated on howmuch individual control we can exert and we ask ourselves, “Why make a changewhen the world may crash and burn anyway? Or why vote when my one puny ballotpaper almost certainly won’t change the result?”

This isn’tthe way to think. The truth is you are part of something powerfulwhether you like it or not – whether you act or not. The question is whichlarger force you are going to be a part of.”

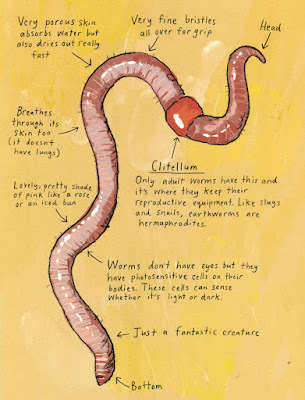

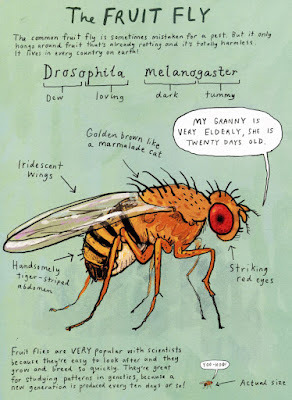

My final non-fiction book with heart is The Observologist, by Giselle Clarkson –it’s‘a Handbook for Mounting Very Small Scientific Expeditions’. This book finds thewonders in the everyday. The closer youlook, the more you see. Nothing is boring. Every creature is busy living &experiencing its own life, with its own hopes and fears, and it feels likesomething to be it.

You can find tiny treasure. There’s usefulness in being bored. This bookis funny but also inspires curiosity and a fierce love of nature, and respectfor small creatures like the humble woodlouse. And that when you are observingand exploring, you are being a scientist. Clarkson doesn’t shy away from givingyou the proper science words for stuff – you are being respected as a scientistwho can deal with the real words.

Being a matchbox fan, Iparticularly liked this spread.

'Just a fantastic creature'

'Just a fantastic creature' 'Golden brown like a marmalade cat'

'Golden brown like a marmalade cat'

'

Keats, in his poem Lamias, complained that “Philosophy (AKA science, especiallyNewton) will clip an Angel’s wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine –

Unweave a rainbow..”

Books likeThe Observologist show how wrong that is – that every tiny thing gets moreinteresting the closer you look, that the more you know about the world, themore extraordinary and strange and wonderful the universe and life on Earth become,and everything is interesting.

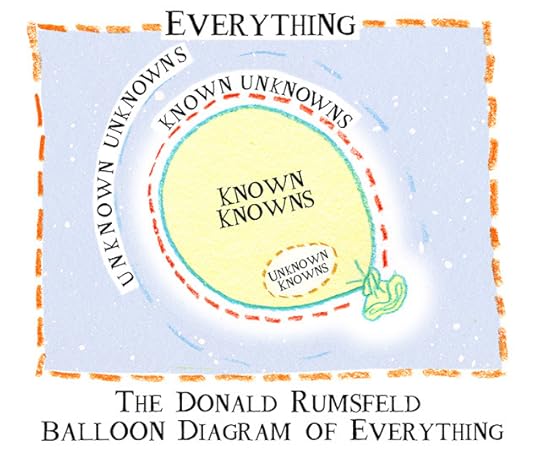

When I made this Donald Rumfeldt balloon diagram of everything, I discovered that as your balloon of KNOWNKNOWNS gets bigger, its skin – the membrane that is KNOWN UNKNOWNS gets biggertoo – so the more you know, the more you realise there is to know – and this isa good and exciting thing.

When I made this Donald Rumfeldt balloon diagram of everything, I discovered that as your balloon of KNOWNKNOWNS gets bigger, its skin – the membrane that is KNOWN UNKNOWNS gets biggertoo – so the more you know, the more you realise there is to know – and this isa good and exciting thing.

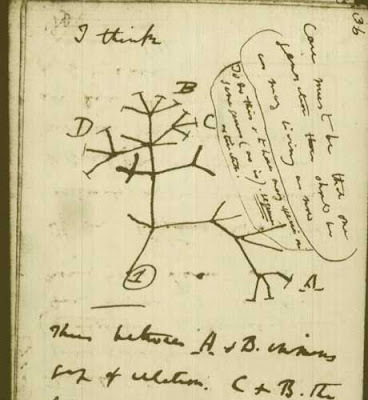

Mary Anning had no idea of Darwin’s big idea, she lived too early. Inher time, creation was all made by God, and animals were all separate creations– humans most separate of all.

Mary Anning had no idea of Darwin’s big idea, she lived too early. Inher time, creation was all made by God, and animals were all separate creations– humans most separate of all.

Darwin’s great idea, sketched in a notebook – was that everything isrelated, it is all linked together in a tree of life: we are woven together andrelated to everything and everyone else who has ever lived on earth, frombacteria to sponges to sharks to tigers to humans. The fact that we’re alive onthis improbable, beautiful, vanishingly rare, precious pale blue dot of aplanet is a miracle, an impossible wonder.

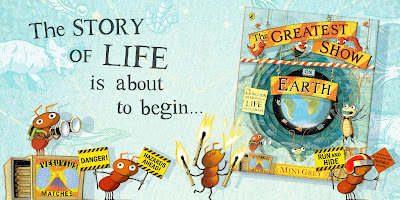

Mini's latest book is The Greatest Show on Earth, published by Puffin.