Interview With Marian Womack

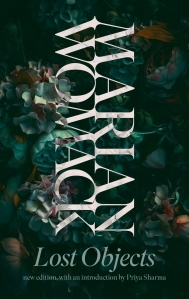

I recently interviewed Marian Womack for the Calque Press revised edition of her incredibly powerful collection, Lost Objects. I loved this set of sf tales, which incisively interrogates the slow catastrophe we’re living though in hauntingly beautiful prose, when it first came out (and reviewed it for the LA Review of Books at the time) so it was a real honour to get to ask Marian some questions about her vision and craft. This new edition of Lost Objects also features an introduction by Priya Sharma and is available to order here.

Q. The more pressing climate change has become, the more fiction has concerned itself with ecological collapse, and the last few years has seen an explosion of novels and story collections which explore environmental crises. Much of this is aftermath fiction. The trope of ‘plucky’ survivors on some kind of pilgrimage through a desolated world, driven by urges and whims opaque even to them, has now become almost rote. It seems to me that the stories in Lost Objects take a very different approach, climatic change depicted not as dramatic upheaval, but slow creep. In ‘Kingfisher’ there is even a question mark hanging over what precisely is being experienced. And even in the post-crisis tales, like ‘The Ravisher, The Thief’, the worlds feel less blasted, more convincing (maybe even more hopeful, though absolutely not glibly so). How did you go about developing this unique way of writing imaginatively about loss and decay?

A. Part of the problem with climate change is that it’s difficult for us to even acknowledge it: this is a clear ‘slow-creep’ wicked problem. As a writer I want to address this distantiation that we experience. I personally am a writer of liminality, rather than certainties. Perhaps this is connected with being a bit of an outsider: I look at English society from the margins, never fully included, so I myself am used to inhabiting these liminal spaces. Understandably, this has seeped into my writing, grounding it firmly in the ‘not-quite-there’. My main interest is in exploring these liminal moments, these grey areas, unsure spaces where boundaries blur and nothing is too clean-cut. Most of my fiction deals with these places, one way or another.

Q. One other feature of much contemporary climate fiction is that it is generally tied to human characters and an anthropocentric perspective. Your stories seem to approach change on a more universal scale and distribute consciousness to the non-human—animal and even insentient (the curious malevolence of the alien world in ‘Frozen Planet’). Was this a conscious choice? What lay behind it? How was it done?

A. All writing is political, right? All art is political. I certainly think that human beings + capitalism are to blame for this mess. I know this may sound a simplistic answer, but we, majorly, are the agents of chaos. I like giving non-human creatures agency in my stories, whether is a garden or a farm that reconquers space, a deer that throws a woman out of her own house, even a massive digital library in my new story ‘Player/Creator/Emissary’—an idea that I anticipated in my novel The Swimmers—all of them have something in common: they are fighting us, quite clearly. I am reframing the human as the main villain here. Perhaps I am also manifesting the kind of world that I would like to pass through? I think humanity’s time has passed, and we are not even aware of this.

Q. A simple question—why birds? Birds are key to so many of the tales—and in ‘Kingfisher’ the eponymous bird becomes totem and then catalyst—the protagonist’s husband dissolves into downy feathers of many hues, and she becomes miraculously pregnant. There is also a strand in that story about writers’ relationships to birds, Milton’s in the epigraph, and both O’Connor’s peacocks and Woolf’s Greek-talking birds are alluded to. What is your own relationship to birds?

A. Birds are beautiful, they are liminal creatures: birds move between realms. There is a song by Lisa O’Neill that I am obsessed with: ‘Birdy from another realm’, where she explains how in the presence of birds we are in the presence of something entirely otherworldly. Then there is their connection with something that truly fascinates me as much as it terrifies me: the idea of ‘deep time’. A bird is our closest connection, and in fact a direct one, with the dinosaurs. How incredible is that? I am obsessed with things that connect us with deep time. My partner gave me a Burmese amber ring recently: it is meant to be about 86 million years old. I cannot even start to imagine the concept of having something that existed then on top of my finger. We are so truly insubstantial. Throughout our lives, we become trapped, at times in cages of our own making. And it’s so hard to understand this while it’s happening. Birds encompass all of this at once: the idea of freedom, but of freedom to escape our world by moving between worlds, between different epochs even, the now and the then… And birds will be here long after we have gone. They are my metaphor for everything that we are not.

Q. Linguistic play and transmutation is at the heart of many of these stories. The protagonists of ‘Kingfisher, ‘A place for wild beasts, and ‘The Ravisher, The Thief’ are translators and a buried etymology is key to understanding the latter tale. How has your own work as a translator and your ability to move fluidly between languages fed into your writing?

A. Have you watched Only Lovers Left Alive? It’s one of my favourite movies. There is a scene when Tilda Swinton is packing to go and visit her lover, played by Tom Hiddleston, and she is not packing clothes, but books, in every language imaginable… Every time I see that scene, I completely relate: if I was immortal, and had all the time in the world at my disposal—Swinton is playing a vampire—I would definitely do two things: learn languages and learn to play instruments. I love the idea of reading what I want, of watching the movies I want, of travelling anywhere and being able to speak with anyone I meet.

I am aware that writing in a ‘chosen’ language is a privilege; but bilingualism, and even multi-linguality, must be celebrated: they allow you to understand somebody else in their own terms, which is outstanding. I am fascinated by this idea of understanding one another, of translation and language as a means of building bridges. Again, this is a political action, even if it sprouts from the act of writing, you are creating a different version of something, with the intention of expanding its reach. Translation can also be ideologically motivated, so as a tool we need to use it with care, be respectful, be aware of what we are doing. I hope that these small ideological actions are what are left in my writing. I write in order to understand the world, I also write in order to explain it, and to offer others the chance to reflect upon it. The possibility of doing so in more than one language, if you can, needs to be taken.

There’s also a more personal reason here: as much as a bridge, moving between languages can be used as a shield: I feel freer to experiment writing in English, to try things out, and to explore possibilities, in a way that writing in Spanish would not allow me to. Spanish for me is the language of growing up with Catholicism being pushed down your throat, or female oppression, in the household, but also outside of domestic spaces, openly, violently.

Q. Lastly, can you summarise your personal aesthetic as a writer?

A. When I published one of my first stories written in English, ‘Orange Dogs’, in Weird Fiction Review, the magazine had the kindness to interview me. I was asked to describe my personal aesthetic then. I hadn’t given this much thought, but three words came to mind at once, and they’ve guided me ever since: Beauty is complicated. I think that simply sentence comprises a lot about what I think about writing, about art. There is beauty in desolation, as much as there is despair in perfection. Everything needs darkness and light to become real. Our world is extremely polarised, and, as I explained above, I understand better the spaces in-between those dichotomies. I am a explorer of the liminal, and my writing wants to become a door to that. I hope some of it manages it.

Marian Womack

Marian WomackPhoto credit: Mewsune 2024