Talk Like an Autistic: Accessible Best Practices at Home & Church

Worlds collide

As an author and editor, I am always on the lookout for exposition. Exposition is when you list a bunch of information rather than revealing it through story. It’s also called “info dumping.” In movies or books, exposition is frowned upon because it’s boring, drags the story to a standstill, loses the audience. Even nonfiction books work hard to find a narrative pace to convey information, because humans are made for stories. We remember them because they connect us to our world and to others. As a parent to autistic children, I have always been wary of the tendency to info dump at children. Though well-intended, many interventions are largely ineffective for the same reasons that they would be ignored by the general population: They’re boring, lack empathy, and rely on info dumping. That made me think of one of the most often requested resources I have resisted making: social stories.

I recently realized why I don’t like social stories. It’s because they’re exposition, not narrative. My children never related to them. They DID love video modeling when they were trying to prepare for a new experience, though. Unlike social stories, which are basically lists of things to do with a loose framework saying that “I will do ___,” video modeling relies on the context of and empathy with another child talking about and demonstrating their experiences. To the extent that social stories work at all, they work off label, because of the way that empathetic teachers and parents modify them to explain them in narrative format. If I take my classroom into the empty church at the end of class in order to walk them through the process of kissing the Gospel, they’re going to watch me and each other in the context. They will understand because they’re living it. They will also understand because by modeling for them and telling them a story, I acknowledge the child’s humanity. It’s personal in the theological sense.

Narrative treats people as persons capable of knowing God. Exposition has the tendency to devolve into treating people like things (tasklists, checklists, objects rather than subjects in their own stories). The most basic difference in how I applied early interventions for my children was that I refused to dehumanize them into behaviors; I refused to act as though their job as humans was to make requests and behave; I refused to start with analysis rather than empathy; I told them stories and made everything a part of stories. Our best therapists were amazing because they used enhanced books and storytelling and songs to engage the kids in building language and modeling in person or on videos to help them build skills. Actual narrative, actual empathic engagement and story-telling, especially if you’re acting it out (facial expressions, mimicry, accents, gestures, dressup, skits, songs), builds up personhood.

What This Looks Like At Home

We are storytellers. We read books aloud. We describe the world in literal ways to make each other laugh. We personify inanimate objects and anthropomorphize animals so we can narrate them. We spend hours every day pausing shows to make quips and point out inconsistencies. We crave narrative, so we “unmask” by giving it to each other. We accommodate our need for stories by telling them, watching them, reading them, listening to them. We sing to each other with and without words. Half of our inside jokes are musical sound effects in everyday contexts.

I’ll turn on the Kiera Knightly Pride and Prejudice movie, lean towards my daughter, and whisper, “Why is she finishing a book at dawn? How was she reading in the dark before that? I think Lizzie might be a fey. She can see in the dark and walks throughout the night to read.” We call this movie “Literate Lizzie” or “Literature Elizabeth” for short to distinguish it from the other film versions of Pride and Prejudice. We mash up the characters with other fandom worlds, figuring out which Middle Earth characters would play Darcy and Bingley and Mrs. Bennet. If you’re thinking, that sounds fun, you are corrrect. It’s very fun. And this fun-having story-telling joy is the primary “intervention” for building language, motor planning, social thinking, and gestalt language processing in my children. We look like we are laughing and telling stories (true), and we are checking all the intervention boxes and meeting learning goals (also true).

I have a particular medieval version of “Verbum Caro” (The Word Became Flesh) that I call my “hold music.” Every now and then perimenopause brain or executive function overwhelm or apraxia or just radical changes of subject leave me with a few seconds of reaching for a word. When that happens, I look at the kids and start humming the tune. Everyone sings along. Sometimes when we’re all tired and goofy, we stand up and do contra dance moves to my mental hold music.

I want you to know this, to see how humanizing, how kind, how fun it can be to treat autistic each others as persons. We have so much fun and joy because we don’t treat one another as things (not even problems, burdens, or tasklists). When you start with radical acceptance, there’s a path for narrative, for joy, for growing to know God and each other. God sings to us, after all, and God is the one in whom we live and move and have our being.

What This Looks Like At Church

Narrative and empathy and personhood have always gone together in the church. In Ephesians we find the men and women Christians speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs. They sang one another into the story of God, showing each other their personhood. St. Romanos the Melodist/Hymnographer wrote hymns for women to sing; when the women of the city took up the songs and sang them throughout their daily lives at wells and in markets and in their fields and at their looms and over the stewpots, the converted the whole world back to the faith. There is nothing so good as singing to remember who and Whose we are.

Next to singing, the patterns we receive from the early church are embodied: those who could would go to the places where Christ walked. Those who were too far away would tell the stories as they walked or as they worked. Extended families and workers gathered in firelit medieval halls to hear not only epic poems but also the lives of saints. Women read the saints’ lives to their households. Men spoke of the lives in their fields. Some saints sang the calendar of saints before them and filled the year and the days with sung stories of God’s love, like St. Caedmon the cowherd who was given the gift of hymns by God and equipped with learning by the guidance St. Hilda; the people were converted through the catchy tunes and insightful words that opened their hearts to know God right where they were.

When we teach about God and the saints, we always act out the stories. We might use a few props like crowns or playsilks, or we might build the setting using modular foam couches. We always go through the actions, the way our forebears used inflection and accents and gestures and movement to tell the story that we also have received.

This approach also overcomes the tendency to treat Bible and saint stories like exposition, like social stories: unrelatable, something to get through, a checklist. So often Sunday school devolves into a task to read a story, color a picture, and maybe answer questions. But what if we treat the stories as living and our students as persons who are part of this living story? What if we sing and act out the stories and narrate our world with the elements we learn from the stories? What if we pattern spot and mix fandoms? This is how we read and reason theologically: to know ourselves and everything in the world in the context of the story of salvation.

How This Works in Sunday School

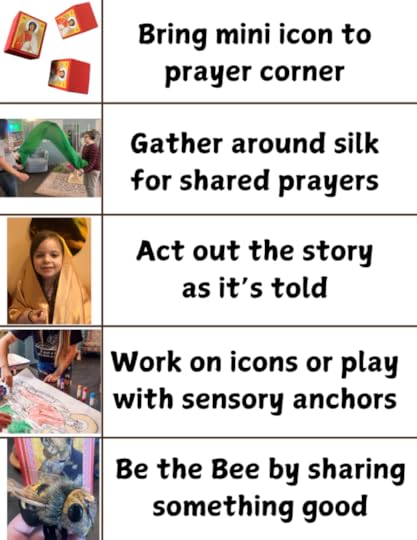

While social stories don’t help with the narrative, setting a pattern for classes does help. A visual schedule showing the class pattern is like a script’s stage directions, showing you where you will go and what you will do in order to participate in the story you are about to tell together. The story of salvation shows up like fractals in every tiny and minute part of our lives and also on the giant universal scale that boggles the mind; we access it by living it; we access it by telling it and acting it out. We follow a pattern because the choreography of the class time shows us who we are.

I’ve shared lots of class templates before (see the Disability Resources tab), but here’s one that works for ALL ages, any ages and abilities. Print it or put it on your tablet and use it as a class pattern to guide you in storytelling through the actions in your classes.

You can also download the PDF here:

class group plansDownloadFor the line about working on icons together, you can work as a class on making a large scale icon on the wall or a banner on a table, explaining and discussing the elements of the image as you work. It’s important that this be a side-along discussion and task, so that the class members are doing something together as they learn. If they’re learning to mix their own pigments or to smoothly apply paint on a separate paper, they should be with each other at one space. The group element teaches people that they are part of the group whose story this is.

Playing with a sensory anchor can mean using large scale props like play couches to build a setting, or it can mean scooping several pounds of mustard seeds in a bin to help you see how productive the one seed of faith can be when it begins to grow, or it can mean playing with a tray of sand and peg dolls to act out a story setting, or it can mean placing waterproof LED candles into a bin of water to talk about the light of the world in Christ’s baptism and our receiving the light in our baptism. The main goal here is that you are touching the faith somehow to make it known.

For the Be the Bee ending, you follow the advice of St. Paisios (free print available HERE) to be like the honeybee that seeks out the good. Use a bee finger puppet or a little bee toy (or one for each person) to go around the room and allow each person to say (using AAC like a speech output device if needed) or point to something good they experienced that day or that week. You can end by taking the bees to the prayer corner, showing that we bring everything back to God.

But This Works for EVERYONE, Not Only Autistics

Yes, exactly. Accessibility means best practices to include EVERYONE in faith, life, and learning. Autistics can’t do without best practices, but everyone thrives with them.

Want to learn more about accessible practices in life and faith? Follow and share, and let me know your ideas and questions in the comments.

The post Talk Like an Autistic: Accessible Best Practices at Home & Church appeared first on Summer Kinard.