SHEDDING LIGHT UPON THE MYSTERY OF LUMINOUS BIRDS - Part 2: ALL AGLOW WITH SUGGESTED SOLUTIONS!

Isthis what a luminous or glowing owl would look like?

Isthis what a luminous or glowing owl would look like?Sceptics notwithstanding, the phenomenon ofluminous birds whose lengthy history I surveyed recently on ShukerNature inPart 1 of this two-part review (click here to read Part 1) is assuredly genuine, but howcan it be explained? Five principal potential solutions have been suggested byamateur naturalists and professional scientists alike down through the ages,and these are as follows:

1) It is due to thebird having made physical external contact with phosphorescent organisms livingon decayed wood in tree holes

The idea behind this suggested solution –the most familiar and extensively documented of the five under considerationhere – is that such contact would cause phosphorescent bacteria, plants, andfungi growing on the wood to become attached to the bird's feathers, thereby yieldingan area of luminescence upon its plumage.

Howa glowing barn owl with a particularly luminous breast might look

Howa glowing barn owl with a particularly luminous breast might look

However, whereas the parts of a bird'sbody most likely to make contact with wood when entering or exiting a tree holewould be its wings and head (brushing against the rim of the hole), the bodyregion actually exhibiting most (or all) of its perceived luminescence in thosespecimens that have been reported has tended to be the breast, with the wings andhead sometimes giving off little (if any) light.

Also, it must be remembered that glowingexamples of extremely large birds, such as North America's great blue heron Ardea herodias, standing 45-54 inchestall, have been recorded – and it seems highly unlikely that birds of thisstature would (or could) inhabit tree holes.

Agreat blue heron (© Mike Baird/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Agreat blue heron (© Mike Baird/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

In addition, and as its common namesuggests, the barn owl, the most popular identity for luminous owls, prefers toroost in barns or deserted out-houses rather than in tree holes (though it willroost in them if need be).

Yet if this option is nonetheless a viableone in relation to certain bird species, a common phosphorescent fungus likelyto be involved is the honey fungus Armillariamellea – a very abundant, widespread, edible species (or species complex,as is nowadays deemed to be the case) that lives on trees and woody shrubs, andsports bioluminescent mycelia yielding an ethereal greenish-blue glow commonlyreferred to as foxfire.

Thehoney fungus Armillaria mellea (©Stu's Images/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Thehoney fungus Armillaria mellea (©Stu's Images/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Indeed, I remember reading long ago afascinating snippet of information demonstrating just how powerful the foxfire glowof this fungal species can be. Edited by Dilys Breese, and published by the BBCin 1981, the multi-contributor book WildlifeQuestions and Answers included the snippet in question, provided bycorrespondent R. Watling, and which reads as follows:

I have often seen the eerielight of the honey fungus in a tropical rain forest. You see all the leaves andstems and trunks, twenty-five feet tall maybe in an old tree, with thisbeautiful glow, just like a silver lady among the trees. And these fungi caneven take their own photographs! If you set up a camera next to one of them, givenenough exposure time, you will get a picture of the fungus all bright andshiny, taken by its own luminescence.

Schistostega

luminous moss inside a Japanese cave (© Dr TerraKhan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Schistostega

luminous moss inside a Japanese cave (© Dr TerraKhan/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Another species likely to play a part inthis particular proffered solution is a phosphorescent plant officially calledthe luminous moss Schistostega pennata,but also known by such charming colloquial names as goblin gold and rabbit'scandle. As noted by bryologist Sean Edwards in a letter published by BBC Wildlife Magazine in April 1994, itsluminous portions are the first cells produced by germinating spores, which actlike thousands of pear-shaped microscopic cat's eyes, collecting andconcentrating even the faintest light. It is often found growing inside (andilluminating) rabbit holes, hence its 'rabbit candle' moniker, yielding agreenish-gold glow.

2) It is due to thebird having ingested phosphorescent microbes

As the luminescence of birds is external,and has actually disappeared in some cases following moulting, one would assumethis to be a phenomenon associated exclusively with the bird's external covering,i.e. its plumage, rather than due to any digestive or other metabolic process(but see also Solution #4 for some ostensible exceptions to this statement).

Of course, we could speculate that if anyphosphorescent microbes were inadvertently ingested with food, they could passout of the bird's body within its faeces, which might then in some way becomesmeared upon its plumage, perhaps during preening, rendering it phosphorescentin turn.

Also, it should be borne in mind that notall phosphorescent bioluminescent fungi are harmless. One such species that ispoisonous is Omphalotus olearius, theso-called jack-o'-lantern mushroom. This orange-gilled European fungus growsaround the bases, stumps, and buried roots of hardwood trees (a relatedspecies, O. illudens, occurs in NorthAmerica). A bird perching upon it may conceivably find itself with fragments ofthis fungus attached to its plumage, especially upon its breast feathers,rendering them phosphorescent, but if the bird then attempts to remove suchfragments by preening, it could inadvertently swallow some of them and therebybecome ill from the toxic nature of this fungus.

Jack-o'-lanternmushrooms (public domain)

Jack-o'-lanternmushrooms (public domain)

Perhaps this is why some luminous birdsthat have been physically examined have been found to be in poor health, suchas Rolfe's barn owl, and the specimen documented later here that was capturedby a Norfolk engineer in his back garden.

Nevertheless, although such a scenario isnot impossible, it is certainly not very plausible as an all-embracingsolution.

3) It is due to thegrowth of feather-specific phosphorescent microbes upon the bird's breastplumage

In some ways paralleling the previous twoproffered solutions, this third one proposes that phosphorescent bacteria orfungi may grow upon a bird's breast feathers if they have become damp or dirty.Propounded by British zoologist William P. Pycraft (1868-1942) among othersduring and beyond the Norfolk luminous owl 'flap', it derives support from thefact that breast feathers are often particularly dense (as with those ofpigeons, for instance), thereby encouraging microbial proliferation upon them.Also, the breast is a difficult region for many birds, especially short-billedones, to reach satisfactorily when preening.

Howan owl with plumage infested with green-glowing phosphorescent fungi may look

Howan owl with plumage infested with green-glowing phosphorescent fungi may look

Furthermore, in his article, de Sibournoted that avian luminescence is particularly powerful during flight. He soughtto explain this occurrence as an effect of superoxygenation, pointing out thatif a medium containing phosphorescent particles is agitated, that medium'sluminescence does increase.

Consequently, this third suggested solutionto the enigma of luminous birds would seem to be the most tenable of the threeconsidered by me here so far. Even so, in view of the comparative rarity ofglowing birds while concomitantly bearing in mind that a very great many birdsmust at some time or another possess damp and/or dirty breast feathers, thissolution still falls some way short of providing a wholly satisfactoryexplanation.

4) It is due tosome internal light-generating metabolic process

There are certain especially mystifyingcases in the luminous bird files that if accurate seem to indicate that thoseindividual birds' luminosity was directly linked not to any externally-sitedphenomenon but instead to their own internal metabolism. For in each case, itsexternal luminosity vanished once the bird itself had died. The earlier-mentionedgamekeeper Fred Rolfe who in 1897 had shot down a luminous sphere in Norfolkand found it to have been a barn owl in very poor condition made no mention ofany such occurrence, but it was a notable feature of the two incidents nowdocumented by me here.

TheJuly 1911 issue of The Irish Naturalistcontained several reports and reviews by different writers appertaining toluminous birds, especially luminous owls, but the report of especial interesthere concerned a luminous specimen of North America's afore-mentioned greatblue heron, as I'll be documenting below shortly.

How a luminous specimen of a great white heron, the whitecolour phase of the great blue heron, might look

How a luminous specimen of a great white heron, the whitecolour phase of the great blue heron, might look

Inhis own Irish Naturalist survey ofreports, C.B. Moffat referred to a very interesting rural belief apparently prevalentin both Europe and North America that I hadn't previously encountered but whichis very pertinent to the luminous great blue heron specimen. Here is whatMoffat revealed:

A belief has longprevailed ascribing similar luminosity [to that of owls] to several of theherons and bitterns, which are supposed to be assisted in their nocturnalfishing operations by a phosphorescent light emitted from the "powder-downpatches" of the breast-feathers, a light that is thought to serve,perhaps, the double purpose of attracting fish to the vicinity and helping thewatchful bird to see them.

Powder-downfeathers are specialized down feathers that grow continuously, in specifictracts, but are only produced by four taxonomically-unrelated bird groups (parrots,herons, bustards, and tinamous). In some such species, the tips of thesefeathers' barbules disintegrate, yielding fine powdery grains resembling dustor talc but composed of keratin; in others, the powder grains originate fromcells surrounding the barbules of growing powder-down feathers. When a birdspreads these grains over its body during preening, they assist in protecting, riddingof parasites, and waterproofing the bird's plumage and skin, but well worth notinghere is that they also confer upon its feathers a noticeable sheen.

James E. Harting(public domain)

James E. Harting(public domain)

Moffatthen stated that wildlife observer James E. Harting had presented a resume ofthe principal evidence relating to this belief within a chapter entitled 'TheFascination of Light' contained in his book Recreationsof a Naturalist (1906). In particular, Harting had referred to a detailedaccount by Philadelphia-based hunter W.J. Worrall of how he had shot a luminousspecimen of the great blue heron. According to Worrall, the heron had possessed three phosphorescent spots – "one infront, and one on each side of the hips between the hips and the tail". Thedescription went on to state that as the fatally-wounded bird expired, so toodid its luminescence, its lustre "disappearing entirely with death".

Of interest, the location ofthis heron's three phosphorescent spots matches the location of some of the paired,dense patches of powder-down feathers in herons, which occur on their breast,flanks, and rump. So, might those phosphorescent spots simply have beenextra-powdery (thence unusually pale and shiny) patches of powder-downfeathers? Worth noting here is that in a Forest& Stream article written by American naturalist Charles S. Westcott andpublished in 1874, Westcott stated that he had experimented in a dark room withthe powder from the powder-down feathers of least bitterns Botaurus exillis, the New World's smallest species of heron,"and found it to be of the same nature as 'fox-fire'". Moreover, J.P.Giraud, Jr., author of The Birds of LongIsland (1844), affirmed that the powder-down of dead herons "gives outa pale glow, not unlike that produced by decayed timber, familiarly termed'light wood,' or 'fox fire'".

A least bittern (public domain)

A least bittern (public domain)

How, then, can we not only reconcilethe above evidence provided independently by Westcott and Giraud that powder-downluminescence is not linked to a bird's life or death with Worrall'scontradictory claim that the luminescence of the glowing heron that he had shotfaded away once the bird itself died, but also (assuming its veracity) explainhis latter claim?

The fundamental biological problemthat Worrall's claim poses was highlighted by none other than Charles Fort – America'spremier collector and chronicler of newspaper cuttings reporting anomaliesacross the entire spectrum of "damned" (i.e. scientifically-rejectedor ignored) phenomena – when reporting in his book Lo! (1931) a second case in which this same luminescence-themedincongruity featured.

Charles Fort (public domain)

Charles Fort (public domain)

Fort referred to a reportpublished on 7 February 1908 in Norwich's EasternDaily Press newspaper (Norwich being a major city in Norfolk), in which engineerEdward S. Cannell of Lower Hellesdon, Norwich, claimed that on the early morningof 5 February when still dark he had seen something shining on a grass bank inhis back garden, and that when it fluttered down a path there he discoveredthat it was a "bright and luminous" owl. He was able to capture theowl, which seemed to him to be ailing, and took it indoors, where it soon died.According to Cannell: "It was still luminous, but perhaps the glow was notas strong as when I saw it first" – i.e. its luminescence began fadingfollowing the owl's death. Moreover, in a sequel report, published by the samenewspaper on 8 February, it was revealed that Cannell had taken the dead birdto a Mr Roberts, of Norwich-based taxidermists Roberts & Son, who claimedin an interview: "I have seen nothing luminous about it".

Needless to say, if bothCannell and Roberts were telling the truth, i.e. regarding the former's claimconcerning the owl's brighter luminocity when alive than when newly dead andthe latter's claim that when he later examined its corpse there was noluminosity at all, this is a most unexpected turn of events. For as Fortastutely pointed out:

Of course aphosphorescence of a bird, whether from decayed wood, or feather fungi, wouldbe independent of life or death of the bird.

Indeed it would.Consequently, the only plausible explanation for any cases like Worrall's heronand Cannell's owl that feature synchronicity between a luminous bird's deathand the disappearance of its luminescence would seem to be that the lattercharacteristic was caused by some intrinsic physiological, bioluminescentprocess – whereby the living bird was actively generating its luminescence viaa specialised metabolic process, which obviously would therefore cease once thebird died.

Might a glowing owl's luminescence in reality bebioluminescence?

Might a glowing owl's luminescence in reality bebioluminescence?

Yet although bioluminescenceis well-documented from a wide range of organisms, it is currently unknown fromany birds. (What has been confirmed,meanwhile, is that many bird species possess plumage that glows in theultraviolet section of the electromagnetic radiation spectrum; but as humaneyes cannot detect ultraviolet light, this particular type of plumage glowremains invisible to us.) Nor has this physiological condition been confirmed from any other tetrapod vertebrate (but click here for my investigation of a highly-controversial Trinidad lizard claimed by some researchers to be bioluminescent).

Of significance,furthermore, as revealed in his earlier-cited American Midland Naturalist article from 1947, is that during hisresearches into glowing birds, McAtee requested fellow American scientist EdwinR. Kalmbach to send him some specimens of the powder-down tracts from Americanblack-crowned night herons Nycticoraxnycticorax, a nocturnal species often claimed by eyewitnesses to beluminescent. He duly tested these tract specimens for the presence of luciferinand luciferase, the compounds inducing bioluminescence in known bioluminescentspecies, but he found no traces of them.

Black-crowned night heron (© ramidos/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.9 licence

)

Black-crowned night heron (© ramidos/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 4.9 licence

)

Consequently, even ifcertain bird species are indeed somehow bioluminescent, they nonetheless mustalso be externally luminescent if like herons they possess powder-downs,judging not only from McAtee's failure to link these feathers tometabolically-induced bioluminescence, but also to the above-reported findingsof Westcott and Giraud that samples of these feathers' powder derived from deadbirds continue to be luminescent. To my mind, however, this seems a superfluousand therefore impractical, implausible duplication of glowing ability.

5) It is due notto birds at all but features non-living BOLs instead

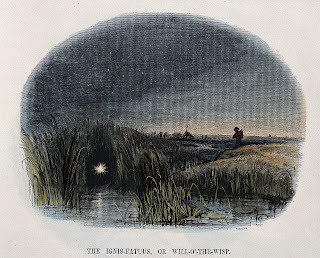

Investigators of the unexplained will bewell aware that all manner of anomalous non-living phenomena involvingmysterious glowing balls of light (frequently abbreviated to BOLs or BoLs) havebeen reported from many parts of the world, and include spooklights, foo fighters,ball lightning, and min-min lights, as well as more familiar, scientifically-resolvedexamples like the will-o'-the-wisp or ignis fatuus (resulting from theoxidation of phosphine, diphosphane, and methane, compounds produced viaorganic decay in marshes, bogs, and swamps). So might reports of luminous birdsin reality involve BOL phenomena and not feature birds at all? Whereas it iscertainly possible that some may have done, examples of such entities beingshot down and found to be birds obviously cannot be explained away like this.Moreover, whereas it is true that the Haddiscoe sightings took place inmarshes, where will-o'-the-wisp activity would not be surprising, others haveoccurred far from such terrain.

Colouredwood engraving of a will-o'-the-wisp in a marsh, by Charles H Whymper (©wellcomeimages.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Colouredwood engraving of a will-o'-the-wisp in a marsh, by Charles H Whymper (©wellcomeimages.org/Wikipedia –

CC BY 4.0 licence

)

Equally problematic for a BOL explanationregarding luminous birds are those examples in which the luminous entities havebeen observed moving in an evidently conscious, self-aware manner. Relevanthere is that in an exact reversal of the above-mentioned suggestion thatluminous birds may be BOLs, many investigators of Australia's most famousunexplained BOL phenomenon, the mysterious min-min lights long encountered inQueensland, nowadays deem it more likely that these glowing enigmas are not ofany meteorological or chemical-based origin but are actually living creatures,specifically barn owls, precisely because of the ostensible curiosity andinquisitiveness that min-mins demonstrate towards their human observers. Hereis a prime example, as documented by me in my book The Unexplained (1996):

In the days of Australia's early European settlers, the Min-Min Hotel was a staging post between Boulia and Winton in western Queensland, whose best-known feature for the people living nearby were the ghostly balls of light that regularly flitted through the air, often white but sometimes changing colour. Still seen today and referred to as min-min lights, these are reminiscent of American spooklights and English will-o'-the-wisps, and display a marked if disconcerting tendency to follow and even taunt their perplexed observers.For example: You Kids Count Your Shadows, a collection of Wiradjuri aboriginal lore and beliefs from New South Wales compiled by Frank Povah [and published in 1990], contains an account of a sheep drover who was checking his flock on horseback one evening when a blue min-min light appeared over his shoulder, and persistently followed him during his work. In exasperation, he chased after it, still on horseback, but was unable to catch up with it – until he gave up, and began riding home, whereupon the min-min cheekily appeared over his shoulder again!

Man vs Min-Min – envisaging a rider in Australia's outback being trailed one evening by a min-min light (image created by me using Grok)An alternative 'living entity' explanation for such sightings may be luminous insect swarms, which have also been suggested as explanations for certain UFO reports (click

here

for my ShukerNature article documenting this possibility), but a curious, inquisitive barn owl, especially if encountered while out hunting at night, could surely explain at least some min-min reports.

Man vs Min-Min – envisaging a rider in Australia's outback being trailed one evening by a min-min light (image created by me using Grok)An alternative 'living entity' explanation for such sightings may be luminous insect swarms, which have also been suggested as explanations for certain UFO reports (click

here

for my ShukerNature article documenting this possibility), but a curious, inquisitive barn owl, especially if encountered while out hunting at night, could surely explain at least some min-min reports. Reading back through my analysis of the five suggested solutions presented here, I think it most likely that as with so many other mysterious phenomena, luminous birds may not involve just a single solution but instead features a combination of different ones, with some cases resolved by one solution, certain others by a second, and so on. For it is abundantly clear that none of the solutions individually provides a comprehensive explanation for all of the cases documented here.

It is sad that such a captivatingphenomenon as luminous birds has fallen out of scientific favour in moderntimes, especially as science is now equipped with so much readily-availablesophisticated technology with which to investigate it thoroughly. Of course,this is due in no small way to the equally sad scarcity of reports nowadays.Saddest of all, however, as noted by David Clarke in his Fortean Studies article chronicling the luminous owls 'flap'reported in Norfolk during the early 1900s (referenced by me in Part 1 of thisreview), is that this scarcity may well be due in turn to how much rarer, as aresult of habitat destruction and poisoning by pesticides, the barn owl hasbecome in Britain and elsewhere during the century or more that has passed sincethe Norfolk 'flap'. Then again, if the numbers of this species, now extensivelyprotected, do eventually re-attain their former level, perhaps this mostdelightful and whimsical of wildlife anomalies may once again attract theattention of professional and amateur enthusiasts and eyewitnesses all overagain, back in fashion at long last.

Closeencounter of the glowing kind!

Closeencounter of the glowing kind!

Finally: worth noting here is thatphosphorescent bacteria were declared the official answer to the anomaly of a legof lamb that glowed in the dark and which had recently been purchased in the Worcestershiretown of Kidderminster, England, during spring 1988. As reported by the Sandwell Express & Star newspaper on12 March 1988, when the discovery was first announced there were fears ofChernobyl-derived radioactive fall-out from its nuclear power station'sexplosion two years earlier. However, Hereford-Worcester's county analyst andscientific advisor Geoffrey Keen rightly rejected this melodramatic notion infavour of phosphorescent bacteria being responsible, thereby solving withSherlockian skills of deduction the curious case of the luminous leg of lamb.

If you haven't already done so, be sureto check out Part 1 of my luminous birds review article here on ShukerNature.

NB – All images of luminous owls includedhere were created by me using Grok.

Moreclose encounters of the glowing kind!

Moreclose encounters of the glowing kind!

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers