108. Tackling inequality in housing design quality 1: routes to success

As the UK grapples with a deepening housing crisis, the focus is often been on the quantity of homes we should build. However, the Labour Party’s 2024 manifesto emphasised a desire for “exemplary development to be the norm not the exception” and promised to take “steps to ensure we are building more high-quality, well-designed, and sustainable homes”.

In other words, it is not just about quantity, but also about quality, and it is not just about quality for some but quality for all.

The reality of poor-quality housing

Unfortunately, in too many disadvantaged areas, poor quality housing development is the norm. As a series of Place Alliance studies have shown, the private market works less well in such places, with lower land prices leading, proportionally, to lower investment in all aspects of the design and delivery of new homes and neighbourhoods. This happens to the point where all quality is squeezed out of private and associated affordable housing, or housebuilding simply becomes unviable.

It is perpetuated in large parts of the country by the disengagement of the public sector from housebuilding and from the proactive governance of design quality. It leads to a failure to harness the power of proactive planning to deliver anything better than standard market products and residential layouts dominated by roads.

The result, in depressed areas, is that poor quality housing development is the norm and routinely accepted by all concerned. The disadvantages that under-privileged communities already suffer are then compounded by having to live with the everyday experience of a poorly designed built environment, with long-term impacts on health and well-being.

A positive shift: learning from success stories

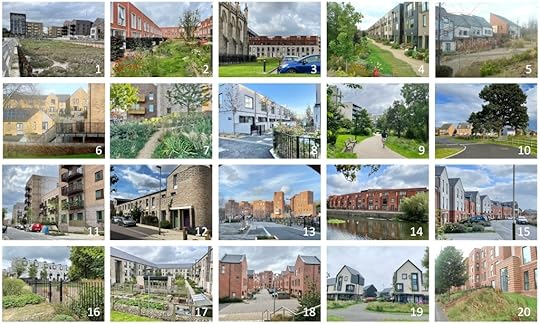

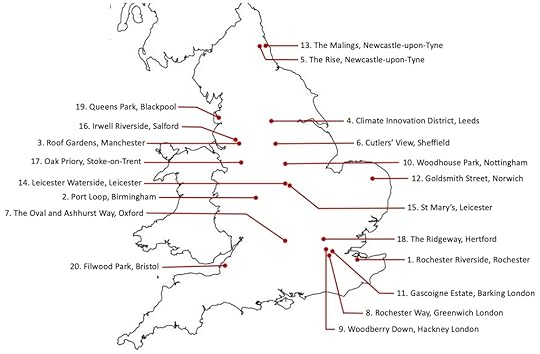

Despite these challenges, high-quality housing development is deliverable in disadvantaged areas. A new report from the Place Alliance highlights 20 projects from across England that have successfully delivered well-designed housing in deprived locations.

The 20 projects represented a broad range of housing tenures and typologies

The 20 projects represented a broad range of housing tenures and typologies The projects covered every English region

The projects covered every English regionTogether the success stories revealed ten key routes to achieving high-quality housing in challenging contexts:

Route I: Creating a place and value through design

Large-scale, long-term placemaking strategies can reshape perceptions of disadvantaged areas by re-inventing the nature of places to define a completely new market. Rochester Riverside in Kent (1) and Port Loop in Birmingham (2) are two post-industrial landscapes being actively transformed into desirable new neighbourhoods, creating ‘place value’ where none previously existed.

Route II: Building a market through architectural innovation

Design excellence can drive desirability and market success, appealing to segments of the market that seek something different, including environmental pioneers. Roof Gardens in Manchester (3) and the Climate Innovation District in Leeds (4) demonstrate this and show how innovative architecture can turn marginal locations into sought-after neighbourhoods.

Route III: An entrepreneurial public sector, sharing the risk in partnership

Many successful projects emerged from strong collaborations between the public and private sectors, bringing together the high ambitions and land holdings of the public sector with the development know-how and resources of the private sector. The Rise in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (5) and Cutler’s View in Sheffield (6) were spearheaded by public-private joint ventures that combined these elements.

Route IV: Utilising under-utilised public infill plots in high value (deprived) locations

Disadvantaged areas often contain underutilised public land with the potential to host significant numbers of affordable homes and deliver other community benefits. This involves the active seeking out and bringing forward of multiple smaller publicly owned infill plots for redevelopment as seen in Oxford’s The Oval and Ashhurst Way (7) and Rochester Way in Greenwich (8). Both set new high design standards while addressing local housing needs.

Route V: Cross-subsidising affordability and design quality

Not all disadvantaged areas lack market appeal. Some, like Woodberry Down in Hackney (9) or Woodhouse Park in Nottingham (10) have inherent advantages (such as proximity to water, open space, or city centres) that can be leveraged to attract high-quality development. This route exploits that locational advantage to attract development interest without the need for risk-allaying intervention or even much (or any) public investment.

Route VI: Simply public sector vision, leadership and funding

When local authorities take a proactive approach, design quality improves significantly. Goldsmith Street in Norwich (11) and the Gascoigne Estate in Barking (12) are prime examples of public-sector-led projects that set new benchmarks for social housing design based on strong public sector leadership across all design / development stages, from inception to delivery, backed by public funding.

Route VII: Shifting the economic equation

Making high-quality housing viable in low-value areas can require public intervention designed to shift the economic equation and stimulate private investment, for example de-risking through public loans and grants, overage agreements on public land, or through regulatory exceptions and forward sales. Leicester Waterside (13) and The Malings in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (14) were of this type.

Route VIII: Economies of scale (across multiple sites)

Using standard house types doesn’t have to mean boring, repetitive architecture. Projects like St Mary’s in Leicester (15) and Irwell Riverside in Salford (16) show how adaptable on- or off-site standardisation can enhance both construction efficiency and aesthetics across multiple development sites.

Route IX: Cutting costs through continual design interrogation

Rather prosaically, the continual refinement of projects through a dual emphasis on cost and quality across the development process can deliver a focus on long-term (preferably whole life) value alongside short-term costs. At Oak Priory, Stoke on Trent (17) and The Ridgeway in Hertford (18), interrogating specifications, procurement practices and post-permissions delivery helped to avoid wasted expenditure while optimising quality within the available budget

Route X: Leveraging community ambition

In some cases, putting in place a fundamental community engagement process, either formally or informally, can help to refine critical design parameters and a defined path to success. Queens Park in Blackpool (19) and Filwood Park in Bristol (20) utilised early engagement to gain public trust, avoid resistance and ensure that the projects met the needs of both existing and new residents.

Conclusion: What Are We Waiting For?

The UK’s housing crisis is not just about numbers; it is also about the quality of homes and places we create. If the 20 success stories prove anything, it is that high-quality housing is achievable, even in the most disadvantaged areas. The ten routes to success show how.

The ten routes to success

The ten routes to successTackling Inequality in Housing Design Quality reveals definitively that while some locations are more difficult than others to develop, if the political will exists, then there are always ways and means of bucking the trend and tackling inequality head on through an investment in design quality.

So, what are we waiting for?

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

Matthew Carmona's Blog

- Matthew Carmona's profile

- 12 followers