Epistemology and Philosophy of Science

For me, epistemology resides at the heart of everything philosophical, because to question knowledge is to inevitably reveal the inherent complexity of appearance, perception, and reality. And philosophy of science is the most vital epistemological extension, because it concerns a shared reality between individuals that appears to be objectively certain.

Nothing philosophical exists in a vacuum, however. Questions of epistemology may involve ethical dilemmas like the trolley problem or the problem of evil, metaphysical conundrums like the existence of a higher power, perplexing mathematical-logical phenomena like different sized infinities or verification asymmetry, or even the supremely subjective mystery of the self.

In fact, the self is a great place for epistemology to begin. Some believe that Descartes' dubito ergo cogito ergo sum (I doubt therefore I think therefore I exist) proves the existence of the self, for how could anything be doubting and ergo thinking if that thing didn't exist? Others argue that the 'I' is presupposed in Descartes' formula, and therefore nothing is proved. Personally I'm in the former camp, because it seems that the objection is invalid due to it shooting itself in the foot; I mean, who is it that is objecting if the objector is nonexistent?

But the previous paragraph is conflating epistemological modes of relating to reality. If something is actually proven, in the sense of it being logically deduced from well-defined axioms and rules of inference, then it is known, and there is no need or possibility of believing it. Bare physical facts are also known, like 'the Sun rises in the east.' As long as the terms in the sentence (formula) are well-defined (Sun, rises, east), we can determine its truth or falsity via observation.

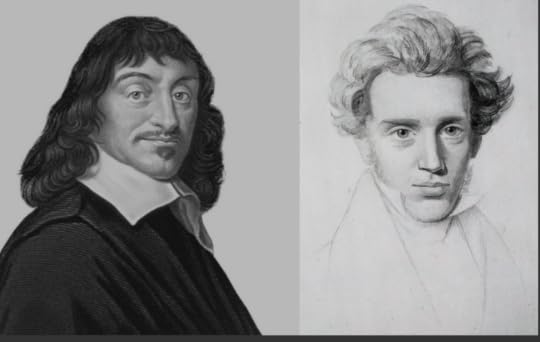

Portraits of Descartes and Kierkegaard

These things Kierkegaard would have called 'objects of knowledge,' for it is truly possible for us to know them. Then in contrast to objects of knowledge he distinguished 'objects of faith,' which, due to their objective uncertainty, are not knowable in that way. The thing of concern earlier − the self − falls squarely into the objects of faith. There is no way of observing the self directly, neither our own nor anyone else's, even though the behavior of biological (physical) bodies seems to intimate (hint at) the existence of selves. It is just as valid to believe in selves as it is to believe that we're merely 'bundles of vague sensory perceptions with names' (cf. Adams).

What Descartes gives us then in his first two Meditations is not a proof, but rather a justification for a belief.

But beliefs need not even have justifications, since they involve that which is objectively uncertain anyway and not given to logical deduction. All one really needs is a leap (another Kierkegaardian insight); but according to Kierkegaard, it is not despite a lack of reason that a belief becomes a leap, but rather the very unreasonableness or absurdity of an object of faith that necessitates a leap being precisely the form in which a belief can come into existence at all.

Scientific ideas, which move beyond mere empirical observation, interestingly straddle the boundary between objects of knowledge and objects of faith. But they are markedly different from beliefs in that they are subject to modification or abandonment if they are falsified or not corroborated, whereas beliefs can be held fast − as they are − regardless of any new observational data. Douglas Adams put it very succinctly by saying that beliefs are essentially unattackable (sacred), whereas scientific ideas are meant to be attacked.

Karl Popper's falsifiability criterion of scientific theories bears semblance to Adams' attackability distinction: "a theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is nonscientific" (cf. Conjectures and Refutations); and so any attempt at falsification of a theory which fails actually strengthens that theory by corroborating it.

For that reason, it would behoove us to have a falsification institute of sorts, whose task it was to try falsifying anything claiming to be scientific knowledge. Such an institute would serve to advance science faster via inadvertent corroboration than any believers in science do via confirmation bias and/or affirming the consequent.

Not surprisingly, those who are devout to the scientific ideas/theories being "attacked" would claim that the institute was against science, but − as shown above − the activity of attempting falsification is assuredly for science.

When it comes down to it, science itself is not about who wins or who is perceived as “right,” it is solely about what is actually true (viz. replicable & corroborated).

Home | Books | Music | Sci-Fi | Works

Published on February 17, 2025 06:59

No comments have been added yet.