Contortionism, Part II

In my previous post, I began to describe my experience of first observing a “Flexibility 101” group lesson at the Cirque School and then a week later taking a private lesson.

After the group lesson was over, I asked several students what motivated them to contort. One, in her thirties, said that as a teenager she had been a gymnast and liked stretching again because it felt good and was more intense than yoga or Pilates. Another said that she was a pole dancer and that the class helped her keep in shape. My instructor related that she performs at private events and that her other students include ice skaters, gymnasts, and dancers. Both my instructor and the owner said that once the desired degree of flexibility is achieved it is alright to take a week off now and then without loss of bendiness. I was also impressed with how strong these people are, defying gravity with their bodies cantilevered in various unlikely positions. My instructor said that contortionists do not pump iron or need to but just gain strength by supporting their own weight in various positions. Also, stiffness with increasing age is not a given, and there are contortionists in their 60’s who still perform. It seems that the mantra “use it or lose it” holds here. (A confirmatory note: I have seen elderly people in Asian countries resting with apparent comfort in a full squat position—buttocks on heels, feet flat on the ground, waiting for a bus or chatting in the market. They have been doing it their whole life, including going to the bathroom without the aid of a raised Western-style toilet.)

Contortion originated in the Far East about 1000 BCE when Buddhist dances incorporated movements of great flexibility. It has become a symbol of national pride among Mongolian nomads and simulates the patterns of their fine arts. Bendy people in other cultures have followed, and some of their achievements are preserved on clay or in clay.

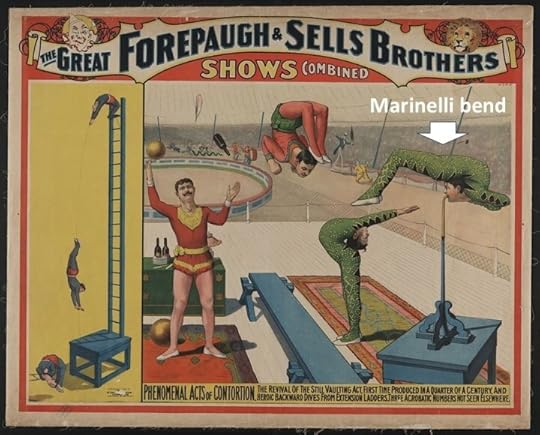

The most difficult pose in contortion is named for H. B. Marinelli (1864-1924). Beginning when he was seven, he was billed as “The Boneless Wonder.” With his teeth he gripped a mouthpiece fixed two feet off the ground and then hyperextended his back until his buttocks contacted the back of his head with his feet extended out in front.

Mongolian contortionists have extended this amazing feat of strength and flexibility by having a second contortionist performs a handstand on top of the one in the Marinelli bend—all supported through just the bender’s jaw and neck—a double Marinelli bend. At least once, and confirmed on a YouTube video, contortionists have achieved a triple Marinelli bend. Equally astounding, another video shows a single Marinelli bender, but she holds this pose for over four minutes—a Guinness World Record. I’d try a Marinelli bend but my dentist advises otherwise.

The post Contortionism, Part II appeared first on MuscleAndBone.Info.