Imagining Fairytale Resistance

The title of this post comes from a book that will be published sometime this year: Women of the Fairy Tale Resistance by Jane Harrington. I have not read the book yet, but of course I will when it comes out. The book is subtitled The Forgotten Founding Mothers of the Fairy Tale and the Stories That They Spun, and it focuses on 17th century writers of fairy tales like Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy.

Hopefully I can write about that book once I’ve read it. But what I want to focus on now is the term “fairytale resistance,” which struck me as soon as I heard it. What would a fairytale resistance look like nowadays, rather than in the seventeenth century?

Let’s start with a story. It’s the story of a young woman who walks through the forest to her grandmother’s house, carrying a basket with bread and wine. Along the way, she meets a man who asks her what she is doing. She tells him that she is going to her grandmother’s house at the edge of the village. She doesn’t know (you probably didn’t know) that the man is a werewolf (a bzou in antique French). As soon as she’s out of sight along the path, the man turns into his wolf form and runs through the forest to grandmother’s house. He eats grandmother up and, in man form again, dresses himself in her clothes.

You know, more or less, the story I’m taking about. But this is a slightly different version in which the young woman does not have a red cap — Charles Perrault added the cap later. This young woman gets to grandmother’s house, and when the werewolf dressed as grandma tells her to get into bed with him, she quickly realizes what’s going on. She says she needs to go out to relieve herself. The werewolf says, “All right, as long as you tie a rope to your ankle. I will hold the end of the rope. That way, I can tell if you try to run away.” She ties the rope to her ankle, but when she gets outside, she unties the rope and ties it around the trunk of a plum tree. By the time the werewolf figures out what’s happened, she has run away. He runs after her, and she can see him chasing behind, perhaps catching up. Is he in wolf or man form at this point? The story does not say, but he can run more quickly in wolf form. Either way, I suspect she is frightened of being caught. The girl comes to a river and asks the washerwomen to help her. They raise the sheets they are washing so she can run over them. When the werewolf arrives and tries to run over the sheets as well, they lower their sheets and he drowns.

This story was told, in slightly different forms, in late medieval France, and it’s the story that eventually became our “Little Red Riding Hood.” I’ve put details from slightly different versions together to create a narrative of my own — as a storyteller would have done at that time.

But this is what fairytale resistance looks like. When you realize that you’re unwittingly gotten in bed with werewolves (metaphorically, and I’m thinking about politics here), you need to get smart very quickly. And it’s very useful to find helpers and allies, like the laundresses in this story.

Fairytale resistance is what the peasantry spoke about, sang about. When you read the folk versions of fairy tales, they are filled with clever young women and men. In the folk version, Cinderella gets her dress from a hazel tree she has watered with her tears — a tree she planted on her mother’s grave. She is helped by birds, and when she goes to the ball (or church, in some versions), she is alone and clever. She gets no godmother to council her until, you guessed it, Perrault. He also came up with the impractical glass slippers. Vasilisa, whose Russian tale resembles Cinderella’s, survives the hut of Baba Yaga through her own cleverness and with the help of a doll given to her by her mother. She becomes Tsarina because she can weave linen so fine that the Tsar has never seen its like. The girl in “Frau Holle” is both clever and kind — she helps the laden apple tree and the oven filled with bread, and she serves Frau Holle so well that she is eventually rewarded.

Originally, fairytale resistance was a way for the peasantry to assert their power in a world that was often unfair and unkind. It meant telling stories about clever characters who defeated figures much stronger than themselves, like Jack and the giant, or Hansel and Gretel in the witch’s house. They did it through being smarter, smaller, quicker — and through helping others who would later help them — and usually through being kind. Even Jack, who is a sort of trickster, gave the gold to his mother. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, fairy tales would be taken up by tellers who were no longer peasants, but were generally not those in power either. Female tellers who might have been aristocrats, but had little control over their own lives in the France of Louis XIV. The poor (sometimes very poor) Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The governess Madame de Beaumont, whose husband had left her destitute. Hans Christian Andersen. The tales changed form, but they remained sites of resistance against those in power. They remained little rebellions in words, little formulas for how you revolt against the ruling classes.

So what were these formulas? Each tale is different, of course. But I think fairytale resistance looks something like this:

You have to be clever. Know what a werewolf looks like. Gather pebbles to scatter behind you, to lead you home again. Figure out how to trick the witch or giant who wants to eat you — being clever can also include being tricky. Even the “simple” third sons in fairy tales are usually smarter than their intellectual brothers.You have to be kind, because we live in a community of washerwomen and apples trees and bread ovens and birds that live in a hazel tree and possible pre-Christian goddesses, and we all need to help each other. Fairy tale heroes and heroines seldom accomplish things completely on their own. They have helpers and allies.You have to be skillful. Fairytale heroes and heroines know how to do things. Spinning the finest linen, sewing shirts out of nettles, cleaning houses on chicken legs — your skills will come in handy, especially the lowly skills that people might not value. Snow White is not just the fairest in the land — she is also an excellent housekeeper.You have to be patient. One commonality among fairy tale heroes and heroines is that they had to wait and endure, whether at home or, as in “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” through a long quest to find the husband you thought was a bear, but was really a prince in disguise, and has now been taken away to marry an ogress.These are all valuable attributes when you’re trying to resist a power structure intent on restricting or even crushing you. Cleverness, kindness, skillfulness, patience — possessing these attributes, but also valuing these attributes more than power and wealth. I think that’s what fairytale resistance looks like. We live in a society that worships power and wealth, but what fairy tales tell us again and again is that those things are illusory–they can be won or lost, and ultimately they are always lost. English fairy tales end with “happily ever after,” but most traditional tales end with a phrase like “and they are still celebrating, if they have not died yet.” In other words, what waits at the end of every fairy tale, acknowledged by the formula, is King Death, before whom wealth and power mean nothing. Ultimately, the important thing is how you lived.

What fairytale resistance also looks like is telling stories about these things, stories that say “Be clever, be kind, be skillful, be patient.” Resist the mighty, find your own destiny, find your community. Know how to tell a werewolf when you see one, even if it’s dressed as your grandmother — or a politician.

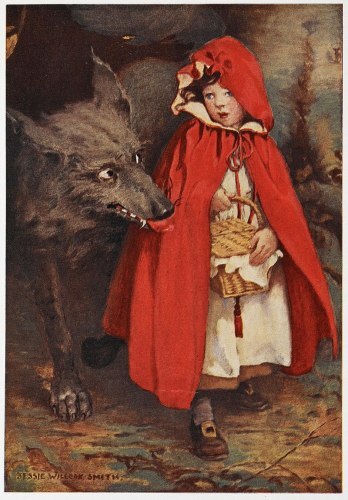

(The image is Little Red Riding Hood by Jessie Wilcox Smith.)