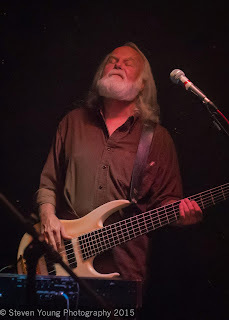

Tom Clift on bass. Photo courtesy of Steven Young Photogr...

Tom Clift on bass. Photo courtesy of Steven Young Photography

This is acautionary tale.

It is a storyof love, and trust, and friendship, and sad lessons. And time. Because wealways think there will be enough time….

Sometime inthe late 90’s, I stumbled upon a chat room for depressed people. Don’t rememberhow and doesn’t matter. My first reaction upon finding it was laughter.

Seriously?Y’all sit at your computers and talk to each other about how sad you are?

My secondthought was: Boy howdy, this is my tribe.

So I joined. Nearlyevery night for months, I would log on and chat away with perfectly imperfectstrangers who turned out to be some of the funniest, most intelligent people Ihave ever encountered. And yes, most of them were or had been clinically depressed.At that time, my life… my soul… was fairly balanced. But while I had learnedstrategies to keep the darkness away, I had not yet followed my journey intotherapy, so I never knew when suddenly I might be spiraling down, trying tohang onto hope. These people, with their love and compassion and kindness,lifted me. Nightly.

One of theindividuals who was frequently in the chat room used the handle botTom. (Myhandle was Savannah, the suicidal sister in Pat Conroy’s The Prince of Tides.)Among those chatting, botTom stood out for three reasons: He was kind. He wasfunny (in a gentle, clever way). He was articulate. (God, I love a man who canspell and punctuate correctly.) And he was incredibly smart.

It happenedone evening that folks in the room were discussing the winter weather, and Imentioned that I was blessed to be enjoying the sun in Southern California.BotTom sent me a private message: “You’re not in Georgia? Are you visiting?Or…?” It took me a sec. Then I realized….

“No,” I toldhim. “Born and raised in and can’t escape CA.”

Turns out thesame was true for him. We decided to meet for lunch and get to know one another.He had described himself perfectly, so when I saw him outside the restaurant, Ifelt immediately at ease.

“Tom?” Isaid.

He held thedoor open for me as he said, “Is your first name Savannah, then?”

I am stilltempted to tell people that’s what the “S” stands for….

We talked fortwo hours—about how we both grew up in Orange County, about how we came uponour blessed tribe of fellow depressives, about love found and love lost, andabout cats—specifically, the two Siamese cat children that remained after Tom’sgirlfriend moved out.

Somewheretoward the end of that two hours, we established that Tom was a musician. Iabsolutely love that he was so low key about this. It would be another year orso before he happened to mention that he had toured with The New ChristyMinstrels and had played with this or that well-known person or band in theL.A./Orange County areas of SoCal.

Tom’s music,my writing, were almost never a focus of our conversations. We met up or calledinfrequently to check in on each other, and our exchanged “How are you doing?”was intentional and meaningful. He knew I was living with adult children andgrandchildren and working fulltime and trying to write my second book. I knewthat he was grabbing gigs wherever he could get them while working a low-payingday job and struggling to afford rent in Orange County.

Life is hard, and depression is a sly companion, slipping in while you’re busy keeping youreyes on all the chainsaws you’re juggling. We kept tabs on each other’s mentalhealth, and after we became Facebook friends, if he saw something there or onmy blog that indicated I was struggling, he would message or call. Those twoSiamese cats—his sweetest and truest companions—lived to the age of 20. Wheneach one passed, I checked in often, as Tom was so heartbroken in losing them,I thought we might lose him.

Over theyears, I saw Tom perform a couple of times, once on a magical night at the L.A.County Fair. He was doing the gig solo, just Tom and his guitar. I’d forgottento bring a jacket, so by the time I’d finished my Australian potato and amargarita, I was shivering and my fingernails were blue. (This detail havingbeen recorded in a personal journal.) But I loved hearing him sing. He satwith me on his breaks, and we laughed together about “fair people.” Iconfessed that I was absolutely one of them.

In 2017,Tom’s sister Jill, his last remaining sibling, passed away. As will happen, herpassing put my friend in mind of his own mortality. At his request, we met at arestaurant with two of his friends to discuss his last wishes. At that meeting,Tom asked me to be the executor of his will. Of course I agreed immediately,feeling honored that he trusted me in such a capacity. I urged him to have aproper will drawn up, naming me as such. We went on to discuss such things asthe disposition of his remains and who would get his guitars. “If I still haveany by then,” he said. And we laughed.

Because ofcourse he was expecting to live a long time.

Fast forwardto 2025. In January, Tom and I exchanged exasperated messages via Facebook.After the pandemic lockdown, we had taken to meeting up for culturalexperiences, touring the Mission Inn in Riverside, visiting the art museum, and indulging in other pleasant outings. But when my old dog was dying in 2024, I had to curtailthose meetups for a while. Then Tom’s phone became unreliable, and he wasnot receiving my messages. Somehow, finally, his phone was sorted, and I wasfree, and we started trying to make a plan to see each other.

“Trying”being the operative word in that previous sentence.

On March 29,Tom tried to call me while I was driving up to the mountains and had no cellreception. When I arrived at my destination, I received the following textmessage from him:

My gabby thing is dying and so

am I wo n

the be long

"My gabby thing." His phone? Was he joking? Or unable to bring to mind the word "phone"? Was he trying to tell me he was dying? I didn't want to believe it was true.

I triedcalling him, but he didn’t pick up. When I began my drive home, I tried callingagain. No answer. I tried several more times that evening. No response. I knownow that he had been hospitalized that day. That he had been suffering fromadvanced gall bladder cancer for months. That he had been sent home that samenight and placed on hospice care. But I didn’t know it then.

My phone rangthe next morning at 5:30a.m. while I was walking the dogs. It was Tom, so Iimmediately picked up. “I can’t reach my water,” he said, his words slurring.“Can you come?”

Every once ina great while in our lives—maybe only once or twice—we are called upon to do bigthings, tasks that require special sacrifice or uncharacteristic spontaneity.This was one of those times for me. I wish with all my heart I could write thatI took the dogs home, got dressed, and drove the hour to Tom’s apartment—aplace I had never been before—and given him his water. Instead, my veryrational brain took over and began a series of questions. To my “Are you sick?”he responded “A little bit.” He wouldn’t tell me how, and finally told me anurse would be coming any time, and he didn’t want to talk anymore. I made himpromise that he would have the nurse call me as soon as she arrived so I coulddetermine what was going on and whether I needed to cancel plans and go to him.

No one evercalled. Tom died a few hours later. This, I learned from a post on his Facebookpage.

The days andweeks following his death have been complicated and sad and frustrating ashell.

He never madea will, as far as we can tell. At least, one has not been found. One of hisnieces, because she is next-of-kin, has been tasked with taking care ofeverything—his apartment, his belongings, his finances… his guitars—all whileshe is grieving his loss.

As we allare, all of those who knew him and loved him. I am meeting his friends andbandmates for the very first time, and they are amazing and wonderful people…and Tom told no one, until the very last hours of his life, that he was dying.

So grief ismixed with guilt, and I push back against it, because guilt, other than makingus ‘do better next time’ or apologize when we need to, is a worthless emotion. I will struggle, though, until I see Tom on the other side, with this:

You hadone job, Murphy. The dying man just needed you to drop what you were doing andcome to him, something he had never asked or expected of you before, and youfailed him.

It's fine. Ofcourse it’s fine. He has crossed over, and he no longer feels any pain and heis joyfully singing with his friends who went before.

But….

My friend, wealways believe that there will be enough time. None of us, however—no matterwho we are—have a guarantee that there will be.