Teaching journalism students generative AI: why I switched to an “AI diary” this semester

Image by Fredrik Rubensson CC BY-SA 2.0

Image by Fredrik Rubensson CC BY-SA 2.0As universities adapt to a post-ChatGPT era, many journalism assessments have tried to address the widespread use of AI by asking students to declare and reflect on their use of the technology in some form of critical reflection, evaluation or report accompanying their work. But having been there and done that, I didn’t think it worked.

So this year — my third time round teaching generative AI to journalism students — I made a big change: instead of asking students to reflect on their use of AI in a critical evaluation alongside a portfolio of journalism work, I ditched the evaluation entirely.

Why did I ditch it? There were two key reasons:

Barriers to complete transparency: I felt that students were not telling me the whole story about their use of AI in their critical evaluationsDecreasing effectiveness: I had already become increasingly frustrated with critical evaluations as a platform for encouraging critical thinking and reading. There’s a whole other debate to be had about the reasons for this, but in most evaluations it felt that critical thinking was being retrofitted onto work at best or, at worst, ‘performed’ (through pasting quotes from literature that hadn’t really been read, for example).So what could replace the evaluation? An ‘AI diary.’

What exactly is an AI diary?An AI diary is a document of every interaction (prompt and response) that the student has with AI. In theory that should mean no selection and editing to put a person in what they think (often incorrectly) is the best light. In other words, complete transparency.

It should also be a living document to be updated throughout production, rather than something to be left until the end: a document of a person’s development and growth, not a snapshot of their destination.

Finally, it should emphasise experimentation and exploration: translating reading into prompts, exploring those ideas through iteration, and reflecting in accompanying notes.

Transparency: giving permission to use AI isn’t enoughI’d arrived at this point after a disappointing experiment with teaching AI to a group of final year undergraduates the previous year.

I had taught a class covering a range of ways to use AI in their work — and how to reflect critically on that, and evidence it. But when I read their evaluations, I noticed something was missing: no one was talking about using AI to edit copy.

Why might this be? I had given explicit permission to use genAI tools to review and identify potential improvements in their writing. And while some might have decided not to use AI to improve their writing, it seemed extremely unlikely that none at all had.

The more likely reason for that gap, then, was a cultural block to admitting to using AI as part of editing and review.

Perhaps, I thought, the critical evaluation format didn’t help. After all, it’s a story with you at the centre: a story justifying your decisions, portraying you as critical and well-informed.

So perhaps a diary would encourage a different genre of story, a less formal and more forgiving narrative. ‘This is what happened‘ rather than ‘This is who I am‘.

We would see.

A diary, not a logbook: continuous reflectionThere are other potential advantages to a diary: could it encourage more ongoing review and reflection, rather than the final judgement that ‘evaluation’ suggests? Could it even build a habit of reflection?

But there are also dangers with diaries: some merely describe events (a logbook). I wanted the type of diary that focuses more internally, on the diarist’s motivations, thoughts and feelings.

So I needed to make that explicit.

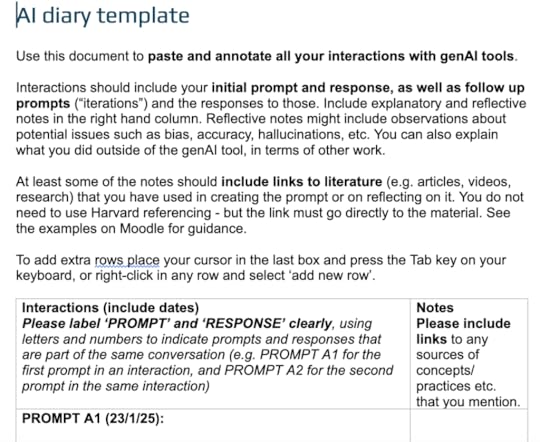

To do this, I created a template for the diary which used two columns: the main column would contain the prompts and interactions — but there would be a second column alongside that, for notes.

Yes, the diary would require a log of every prompt and response — but it would also require some form of reflection alongside those. Why did you write the prompt that way? Did the response demonstrate a particular issue with AI, or lead to a new thought? How could you improve the results?

The AI diary template given to students

The AI diary template given to studentsNot every prompt and response would need a note — but the presence of the column should provide a reminder to stop and think, review and record.

Prompts are an expression of knowledgeWhile developing the AI diary I came across a timely quote from a piece of research on prompt engineering and education:

“Students can articulate prompts that reflect their grasp of a subject, showcasing their comprehension.”

Put another way: the quality of interactions with genAI reflects the quality of a user’s knowledge and engagement with research — and can be assessed as such.

One very explicit example of this is teaching ChatGPT (or Gemini/Claude etc) a practice or framework that you want it to apply. A prompt which explains the 7 angles of data journalism or diversity guidelines or the SCAMPER technique shows the extent to which the writer understands those.

Even better, it provides a reason to understand those, and an opportunity to apply and engage with those concepts in a more dynamic fashion (including, crucially, correcting the AI if they misunderstand).

The diary, then, should include prompts that demonstrate that knowledge: an invitation to train ChatGPT etc. what you mean when you ask it to do something.

It’s not just the diary that becomes regularIntroducing the AI diary meant another big change: instead of teaching a ‘class on generative AI’, we would need to talk about AI from the start of the module, and throughout. But that’s a subject for another post.

Meanwhile, the assignments are in. I’ll let you know how it went…